Issue 19 of Wisden Cricket Monthly includes a special feature on the greatest cricket books ever written, which, before delivering a final verdict, narrowed it down to seven wonders of cricket literature. Supported by Rathbones.

And so WCM’s cast of luminaries and loudmouths settled down to debate, discuss and despair over the shortlist of seven. The task was as simple as it was preposterous: to consider what makes a great cricket book, and why some books stay with us forever, before seeking some kind of consensus to decide the best of the best. Here’s how those discussions unfolded.

How do you judge the greatest cricket book ever written?

Book #1: Coming Back To Me – Marcus Trescothick

Trescothick’s autobiography was released two years after his retirement from international cricket

Trescothick’s autobiography was released two years after his retirement from international cricket

Jon Hotten [chairman]: Lawrence, you’re at the coalface of this intersection between writers and cricketers. What do you think was the significance of the Trescothick book when it came along?

Lawrence Booth: As ever in these instances you go back to Neville Cardus, who said you should never be rude about autobiographies because you never know who’s written them… But I think what Marcus Trescothick did fundamentally was to open up a debate on mental health. What comes through in the book to me is anxiety. Was it profound anxiety or was it depression? And we never quite get to the bottom of that. Which is not to belittle his experience in any way because he was obviously deeply distressed at times. But I think there were wider questions that possibly went unexplored.

Daisy Christodoulou: I loved him as a player. He always felt like quite an uncomplicated cricketer. A batsman who saw it and hit it. And I guess in that sense it’s a good reminder – he seemed like such a straightforward cricketer but he actually had these deeper issues going on. In some ways the book’s almost a bit dated now because so many others have come in its wake. It was definitely a trailblazer in that sense.

The feature on the finest cricket books ever written is in issue 19 of Wisden Cricket Monthly

The feature on the finest cricket books ever written is in issue 19 of Wisden Cricket Monthly

JH: And in terms of the prose, Will?

Will Fiennes: First of all it’s hard to overstate the importance of this book. And actually, what’s interesting reading it now is how already it seems not such big news and it’s easy to forget that in 2008 to have spoken openly about depression and anxiety in that way was a big deal. But it has to be said that the bulk of it is really quite a familiar sporting autobiography. Sentence by sentence, it’s really pretty flat. I’m not saying that the chapters all end with ‘Needless to say I had the last laugh’ but it’s in that ballpark.

Frances Edmonds: It reminded me of Tony Adams’ book [Addicted]. It was a very interesting thing to read about top sportsmen talking about real mental health issues. It’s great that it was written, and that the issues have been explored, but for me it wouldn’t be at the top of my list.

Phil Walker: It highlighted to me the quiet despair of so many cricketers, whose stories would have predated his story and the question struck me: how many would have gone through something like this in the past in silence? Who would have hidden in a dressing-room culture marked by machismo and stiff upper lips and all the rest of it. If Trescothick’s book did anything I think it opened the door to a more sensitive and open discourse around sport and that these characters that we revere and adore, these gladiatorial figures, are not indestructible.

Book #2: Golden Boy: Kim Hughes and the bad old days of Australian cricket – Christian Ryan

JH: Kim Hughes, the former Australian captain, is the subject of Golden Boy by Christian Ryan. Hughes is probably most famous for a single image, breaking down in tears at a press conference as Australia captain. Will, I know you’re an admirer…

WF: I found this book incredibly exciting and an eye-opener. I was thrilled by it. In some ways it’s like a great Australian novel. Interestingly he [Ryan] didn’t collaborate with Hughes on it. He interviewed almost everybody else, so there’s a strange absence at the centre of it that’s filled in by all these other voices. It’s a portrait of Hughes but also of Australian cricket in the second half of the 20th century. Hughes personifies something mercurial, ethereal, this artistic flair alongside these macho, rugged, brawny bruisers like Marsh and Lillee. It’s told with such lyricism and tempo. I found it absolutely enthralling and a real revelation.

Kim Hughes and Mike Whitney during the 1981 Ashes series

Kim Hughes and Mike Whitney during the 1981 Ashes series

Tom Holland: An incredibly painful book. It’s about how awful the disconnect between cricket as a team game and an individual sport can be. Hughes’ brilliance as a batsman is magically evoked but so also is the fact that he’s never going to fit into either of these two golden ages of Australian cricket. Even the title – ‘Golden Boy’ – makes incredibly painful and ironic play with that. I agree with Will, it does have something of the tragic stature of the novel.

LB: It’s a story of bullying. I think the great genius of this book is the absence not just of Kim Hughes but also of Lillee and Marsh. He can’t get quotes out of any of them but it works better for it. And what that forces Chris Ryan to do is to talk about everybody else. It’s about the difficulty of being a sensitive man in 1980s Australia. I think it’s the best written of the seven books here.

WF: Hughes says that he wants to play for the joy of it and to give people wonderful memories; Lillee and Marsh just want to win. And it dramatises this battle of temperaments. I think it’s quite a profound book.

Book #3: Beyond a Boundary – CLR James

JH: Let’s talk about the elephant in any room as far as cricket books go. It’s the oldest book on the list, published in 1963. Where do we think it sits today?

DC: It’s magnificent. There’s so much to it. The first half is very different to the second. We have these individual portraits of Constantine and George Headley and then this disquisition on back-foot play, then some history of Trinidad and then the state of county cricket in the Sixties, and then a chapter on Grace! In a sense that’s its charm, but there are bits that are patchy. I loved in particular the bits on Constantine. It moved me to tears, that relationship. It’s astonishing from a modern perspective. This is the 1930s in Nelson in Lancashire, and you have Constantine and James, two West Indians, pitching up there.

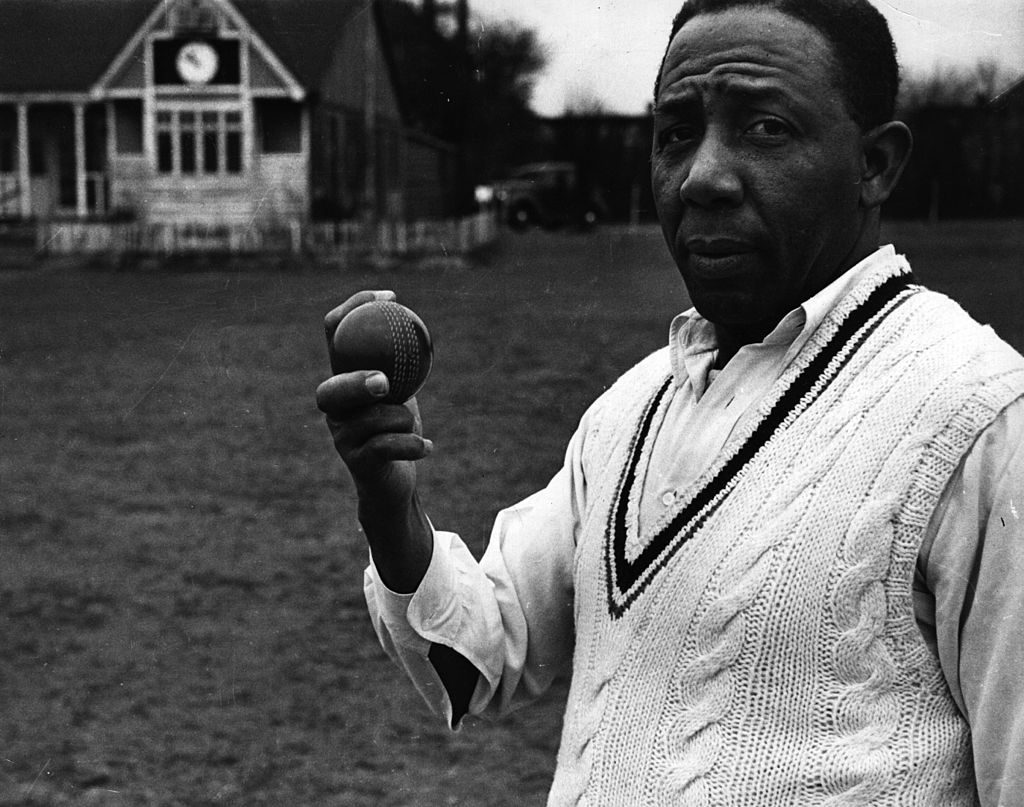

Trinidad-born Learie Nicholas Constantine (1902 – 1971) also achieved notable success in politics and race relations

Trinidad-born Learie Nicholas Constantine (1902 – 1971) also achieved notable success in politics and race relations

PW: The first half stayed with me a lot longer than the second. It could have perhaps done with a good editor. But there was a purity to it as well, it’s unbridled and untouched. There’s an astonishing section about an old Trinidadian cricketer called Wilton St Hill, who’s this tall, willowy opening batsman, one of the first black Caribbean batsmen to play for the West Indies, and he describes the contest between St Hill and this fast bowler called George John, which is a great Steinbeck name straight off the bat, and it all takes place just outside his bedroom window, from where he was “perfectly positioned, just behind the bowler’s arm”. And he describes the leg glance/flick of St Hill as one of the most beautiful and profound things he’s ever seen, and when he describes it, me being hopelessly modern, I see Viv Richards in it, the slightly braced front leg, leaning over to the off-side, keeping his balance and flicking it anywhere he wants. It’s the cricketing descriptions that stay with me.

TH: In the intro to his chapter on WG Grace, he writes: “A famous liberal historian can write the social history of England in the 19th century and two famous socialists can write what they declare to be the history of the common people in England and between them never once mention the most famous Englishman of his time.” He then goes on to write about Grace and place him brilliantly in the context of his time. He’s making the case for cricket and sport generally as being of immense cultural and therefore historical worth. And he’s writing all this in 1963.

FE: Prior to my embarking to the West Indies and writing Another Bloody Tour my editor at the time insisted I went to Brixton to see CLR James, a very elderly man by then with these extraordinary iridescent blue eyes. I have never seen eyes like that, and we ended up having a really great chat. We had a long conversation about what he thought cricket meant and what he saw in the game was the way the British Establishment rolled out its rules through the medium of cricket. How to behave, what behaviour meant, we created ‘Empire’ based on these rules and sought to make those we colonialised comply with them, while ourselves not necessarily doing so…

LB: There’s a fundamental sadness at the heart of the book that James himself acknowledges. In that he grew up and was educated on everything English, he read Vanity Fair 20 times, and it wasn’t until he matured intellectually that he realised that he didn’t really know much about the Caribbean. So this is the story of Empire, perhaps without even realising it, it’s the story of how Britain subjugated the rest of the world, and did it through cricket. James realises this, but by then it’s almost too late, and it’s incredibly poignant for that reason.

Book #4: The Unquiet Ones – Osman Samiuddin

JH: In a sense Beyond a Boundary is of a piece with The Unquiet Ones, Osman Samiuddin’s history of Pakistan cricket, the most recently published book on the shortlist.

TH: It’s not just a history of Pakistan cricket, it’s a history of Pakistan, and it brilliantly makes the case for cricket’s significance as a prism for looking at this country that’s ripped out of the flesh of British India. There are a lot of accounts of how they set up cricket stadia in the wilds of nowhere and essentially that is what is happening with the Pakistan state. So the process by which the Pakistan cricket team goes to England and wins its first Test match there, the dynamic of the Indo-Pakistan relationship, the tension between the British-educated elite and the people who don’t speak English, the way in which Islam impacts in the later years – all of these are crucial aspects of Pakistani history, and the genius of this book is that it makes you see this, and it does it in a way that is massively entertaining.

WF: I found this a very poignant book actually. The violence of Pakistan’s beginning, the rupture of 1947, the many dark periods since then, and the way that cricket functioned both as an escape as well as something integrally woven into daily life. And the pen portraits are fantastic, from Hanif Mohammad’s triple century to Wasim Akram and the sadness of Mohammad Amir and the match-fixing scandal.

DC: There were also some genuinely funny moments. The bit when the match-fixing stuff is starting to surface and Imran Khan gets wind of it and he says to the team, “If anyone’s involved in this it’s an outrage, so I’ve taken all of our winnings and I’ve put it on us to win”. And Samiuddin does it so well, adding that the three players who were most under suspicion each turned in brilliant performances.

JH: Lawrence, is it important that Osman, a Pakistani, is writing this book?

LB: Absolutely. The ’92 tour was a classic of the genre. The whole debate about ball tampering: Allan Lamb brought it up in the Daily Mirror, there were court cases, the English papers piled in, and yet of course when England won the Ashes through reverse swing, there was no question that it was anything other than the brilliance of the bowling.

A Pakistan series draws to the surface a certain poison in English attitudes to the rest of the world. It’s always Pakistan. And it’s all there in this book. It needed a Pakistani to be able to say it.

Book #5: A Social History of English Cricket – Derek Birley

JH: Tom, how much of this is conventional history?

TH: It’s all history. Rather like the previous two books, it’s an expert history of a place, this time of England, seen through the prism of cricket, and Birley’s point really is that cricket as a metaphor and as a mirror held up to English social history is sufficient to provide an insight into the parabola of the past 300 years. And one of the ways in which it’s an excellent work of history is that it’s often very, very funny. It exposes the degree of hypocrisy and sham that underlines a lot about what the Victorians in particular made for cricket. Even as it’s inflating the mythic role that cricket has as the mirror held up to England, it’s simultaneously puncturing it. I think it’s a wonderful book.

LB: It’s essentially a history of hypocrisy, which itself is the history of English cricket. He cuts to the quick on ‘walking’, where the English ‘gentleman’ insists on walking because he believes in the spirit of the game. Whereas Birley’s point is that the amateur English batsman is not going to be told what to do by the professional umpire and so took the law into his own hands – that’s why he’s walking.

PW: The title is the most misleading of any cricket book I’ve ever read. It sounds like a dry account that you’d find mothballed in a dark room somewhere in a library but it’s pretty vibrant and witty and irreverent, and his political leanings are quite clear.

TH: Yeah, the irony of this book is it’s actually a vastly more ‘Marxist’ book than Beyond a Boundary. It’s always aware of the effects of class and money.

Book #6: Rain Men – Marcus Berkmann

JH: We have talked a lot about the pros, but almost all cricket is amateur cricket. Frances, perhaps you can kick us off on the notion of the inept amateur, and the humour of it.

FE: To me the issue is this: the people who can play cricket brilliantly can’t write, and those who can write brilliantly generally can’t play cricket! With Rain Men and others like it you have absolutely spectacular writing, and rather more than the protagonists at the elite level, they provide these great insights into why anyone plays any game, insights into human relationships, human values, fairness, and they come up with greater insights into the human condition than the often rather boring stories from those at the top. And these sorts of books have far more resonance with the public than the elite sportsman’s book.

Is Rain Men the greatest book on grassroots cricket?

Is Rain Men the greatest book on grassroots cricket?

LB: Marcus Berkmann invented a genre, that of the hopeless amateur. And still nobody’s ever done it better. He’s not invented wit or humour in cricket, but he has invented a genre about being useless and that in itself is another very English strand. Very readable, very enjoyable.

WF: I think Rain Men sounds like Marcus is talking to you, and that is no accident. It’s also very nicely structured, over the course of a year, using the months not just as ways into the cricket season but as hooks for little essays on different aspects of cricket. Because it’s over a year, you get a feeling that the end of one cycle has come and the next cycle is beginning, suggesting a cycle going on into infinity. It’s a congenial book, it’s so warm, but I don’t feel that it’s letting me in on something bigger about how people relate to one another. The portraits of the characters are little vignettes, but I don’t know if they have the kind of amplitude around them that you’d look for in a really great book.

TH: I actually disagree with that. I think it’s a book with a deep sense of pathos and also bathos. It’s the story of a man who yearns to be a great cricketer but never will be. And that is the stuff of English humour. That is the essence of all the best-loved British sitcoms. It’s the mismatch between aspiration and achievement, and I say that with some feeling!

Book #7: Chinaman – Shehan Karunatilaka

JH: The final book in our list is a novel. It’s a magnificent book, set in Sri Lanka, and its central rubric is the search for a mystery spinner called Pradeep Mathew and the old soak of a journalist that’s after him.

WF: This was a great surprise to me. It’s such an original and quite experimental novel, but it’s integrated into so much real cricket that you genuinely don’t know if this figure Pradeep Mathew actually existed or not. And again there’s this contrast between the great sportsman and the observer, who’s physically enfeebled and can only dream of that sort of athletic wonder and achievement.

JH: And in terms of what I was saying about it being a book about Sri Lanka, which isn’t necessarily a subject that we read a lot about.

WF: I think we’ve had three books on the list – this, plus Beyond a Boundary and The Unquiet Ones – in which cricket does figure as the colonial legacy of imperial bequest, and there’s an ambivalence in all three books. There’s a great richness to these societies through cricket, but it’s only because they’ve been colonised and oppressed.

DC: The thing that links it to Rain Men and the whole idea about thwarted ambition is right at the beginning when he’s talking about his fellow journalists – failed artists, scholars and idealists who now hate artists, scholars and idealists – and that made me think of a lot of ex-cricketers commentating… so often you see it in the commentary box when an ex-player is being nasty, and you think, why are you being so nasty? And to me it’s so transparent from the outside that it’s about bitterness.