India have won T20I series against Bangladesh, West Indies and Sri Lanka in recent months, while drawing against South Africa. But nine months from the Men’s T20 World Cup, they still look an unfinished product.

Rohit Sharma’s return from a break and Shikhar Dhawan’s recovery from injury have reunited India’s all-conquering top three in their 16-man T20I squad for their tour of New Zealand. It’s a most welcome development, given how prolific each of Rohit, Dhawan, and their captain Virat Kohli has been in the shortest format. With KL Rahul, too, back in form and making a serious case for a top-order spot, it gives India the kind of security that is needed in a World Cup year. However, has any of this brought India closer to discovering their best T20I team?

The short answer is yes and no. Rohit and Kohli ended 2019 as the joint-highest run-getters in T20Is. Dhawan’s experience, white-ball credentials and penchant for the big stage mean that anytime he isn’t injured, he is a prime candidate for selection. But what of the rest?

There is little doubt that India haven’t cracked the code in the shortest format. That they are ranked fifth at the same time they have dominated the two longer formats, where they have built a near-invincible aura, speaks to that fact.

India’s T20I squad for NZ tour announced: Virat Kohli (C), Rohit Sharma (VC), KL Rahul, S Dhawan, Shreyas Iyer, Manish Pandey, Rishabh Pant (WK), Shivam Dube, Kuldeep Yadav, Yuzvendra Chahal, W Sundar, Jasprit Bumrah, Mohd. Shami, Navdeep Saini, Ravindra Jadeja, Shardul Thakur

— BCCI (@BCCI) January 12, 2020

Kohli defended the low ranking last month, when he said: “T20 is a format where you can experiment a lot more than ODIs and Tests. You want to give chances to the youngsters in the shortest format. We have not played the strongest XI together in T20Is, so rankings cannot be considered. We have the mindset that we will not focus on the rankings. Now, heading into the T20 World Cup, we need to take our best team to the field. We would probably be playing our strongest XI going into the World Cup.”

But what is that strongest XI? It’s too soon to fully answer that question, because nine months is a long time in international sport. But there are certainly gaps that the best XI, whatever it ends up being, needs to plug.

Some of those remedial measures have already begun to be applied. For one, the West Indies series showed us that India have finally begun to acknowledge that they need to be more proactive in finding the big hits. But, just as India’s problems are not onefold, overt aggression is no one-solution-for-all.

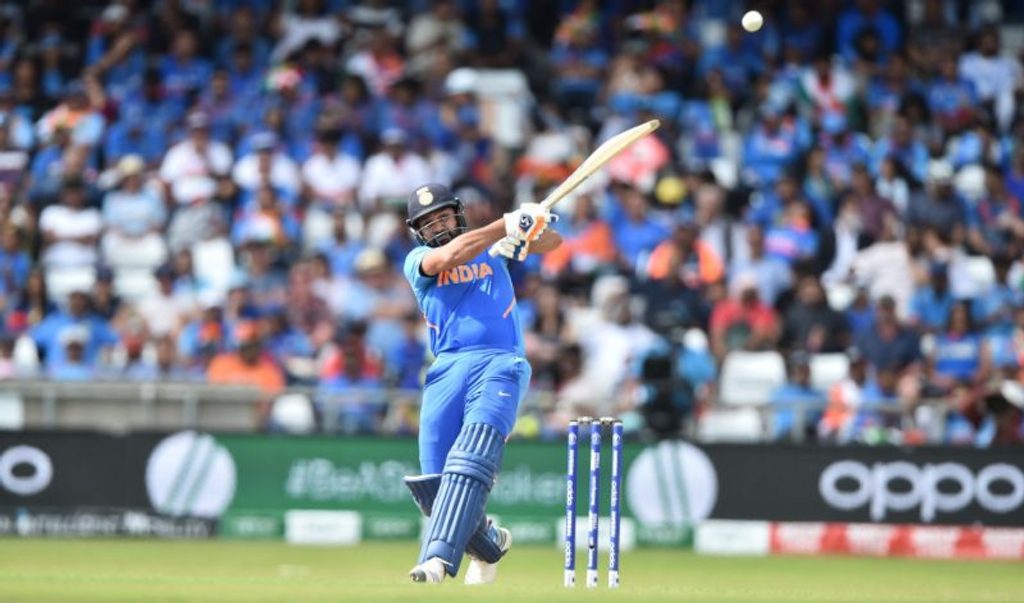

Rohit Sharma’s knock against West Indies in Mumbai typified India’s change in approach to T20 batting

Rohit Sharma’s knock against West Indies in Mumbai typified India’s change in approach to T20 batting

Among the top 10 T20I nations in 2019, not only did India’s batsmen score the most number of runs, they also topped the fours and sixes charts. Impressive as that is, it begs the question of why India suffered the third highest number of defeats among those teams and why their win-loss percentage was seventh best. This, despite having played more games than any of the other teams on the list.

One of the answers to that is part of what has constituted the same old debate that has raged on during the Kohli regime: the gulf between the top three and the middle order. Out of the 188 fours that India’s batsmen struck in 2019, 133 came off the bat of a top-three batsman. Likewise, the top three also accounted for 68 of the 117 sixes struck during this period. They made 63 per cent of the team’s runs, and 13 out of 16 half-centuries.

By contrast, the middle order, though it featured 13 players, nearly twice that of the top order, made just three fifties. While the top order’s number of runs, fours, sixes and fifties was the best among the top 10 countries, the middle order doesn’t feature in the top three in any of those criteria. Moreover, the average drops by about 12 points, and the strike-rate by about five.

It’s a sign that India aren’t finishing their innings as strongly as they are starting them. Kohli has tried to address the issue by dropping himself down the order and giving players such as Sanju Samson, Shreyas Iyer and Rishabh Pant a run at his favoured No.3 position. That’s a step in the right direction because India’s middle-order worries have often been the result of a lack of exposure. It’s also proof of Kohli’s “experimentation” remark, and the sign of a flexible team management, whose decision-making will be situational as much as it is strategic and, when needed, won’t be averse to high risk.

Nonetheless, there remains a need for more big hitters, or at least a quick starter from No.4 onwards. Iyer hasn’t fit that mould, and Pant’s low probability of success so far doesn’t make him a safe long-term prospect. Perhaps pushing Rahul down to that position might be worth a shot as well. Though Rahul has shown an inclination towards batting at the top, it’s his chance to show that he isn’t one-dimensional. And with the range of strokes at his disposal, some adaptability would go a long way in making for a more fluid line-up.

Washington Sundar has been brilliant at containing batsmen in the Powerplay

Washington Sundar has been brilliant at containing batsmen in the Powerplay

As was the case with the batting, some of the numbers with the ball, though impressive, don’t necessarily reflect consistently good work. India’s bowlers were the most successful among the top 10 countries in 2019, snaring 83 wickets. But their average (30.21) and strike-rate (22.3) were only above those of Pakistan, signalling a need for more effective wicket-takers, especially ones that can break partnerships. Their economy rate of 8.10 also puts them in the lower half of the table, at No.6.

Does that mean, then, that the trio of Deepak Chahar, Shardul Thakur and Navdeep Saini are placeholder selections while Jasprit Bumrah first, and Bhuvneshwar Kumar now, recover(ed) from injuries? Arguably, the combination of wickets, swing and raw pace that the younger trio offers, the Bumrah-Bhuvneshwar-Shami combination does too. With the added advantage of experience, a buffet of inch-perfect yorkers and slower ball variations, and control at the death.

Likewise, Washington Sundar has proven his ability to check the flow of runs as a Powerplay specialist. But he has done so at the expense of splitting up the wrist-spinning duo of Yuzvendra Chahal and Kuldeep Yadav. Will India risk picking the off-spinning Sundar over their two proven wrist-spinners in the swinging conditions of New Zealand or the flat pitches of Australia? Economy or wickets? Contain the threat or extinguish it at the cost of some extra runs?

India travel to New Zealand without Pandya and Bhuvneshwar, two sure members of the contingent that will take the flight to Australia. There is also the Indian Premier League to consider: a breakout season for a young star or two is sure to get more heads scratching. And who knows what path the Dhoni will-he-won’t-he mystery might take?

India have certainly come a step closer to figuring out their best T20 approach. But the hunt for the 11 best men who will execute that approach remains on.