Under a “sealed bid” system the winning captain would have choice of innings but must concede a pre-declared number of runs to the opposition, writes David Franklin.

This article first appeared in issue 7 of The Nightwatchman, the Wisden Cricket Quarterly

Buy the 2018 Collection (issues 21-24) now and save £5 when you use coupon code WCM6

Originally published in 2014

Anton Chigurh, the villain of Cormac McCarthy’s No Country for Old Men, plays a simple game with those unlucky enough to cross his path. One toss of a coin decides their fate: heads they live, tails they die. His brutality is fearsome indeed: a potent cocktail of death and recreation bearing all the hallmarks of a psychopath.

The ICC has come in for criticism of all sorts during its 105-year existence, but no one has so far accused its officials of such cold-blooded malice. And yet there are pitches around the world on which captains, waiting in suspended animation as the coin falls, must see in the shadow of the watching match referee the spectre of Chigurh. Lose the toss, lose the game. No losing captain in today’s media-savvy era would ever go so far as to say that the toss decided the match; plenty, of course, would want to.

It is worth examining the effect of the toss in the context of a proposed alternative. Under a “sealed bid” system – to be discussed later – the winning captain has choice of innings but must concede a pre-declared number of runs to the opposition.

The toss has, over the entire history of Test cricket, provided a slight but clear advantage to the winner. Of the 1,397 matches that have produced a winner, 737 of those (53 per cent) were won by the team winning the toss, and 660 (47 per cent) by the team losing it. (This is a statistically significant ratio at the 95 per cent confidence level, suggesting the perceived advantage is unlikely to be the result of natural variance alone.)

Steve Smith tosses the coin next to England captain Joe Root in the 17/18 Ashes

Steve Smith tosses the coin next to England captain Joe Root in the 17/18 Ashes

Batsmen playing for the team winning the toss have averaged 32.81; those playing for the team losing the toss have averaged 31.40. By multiplying the difference between the two (1.41) by the number of wickets each team has at its disposal in a Test match (20), we can quantify the advantage: winning the toss is worth, on average, 28 runs – or just under one wicket.

The shift towards covered pitches from the 1970s onwards had a significant effect on this figure. In the years between 1877 and 1969, the toss was worth 40 runs on average. With uncovered pitches tending to deteriorate as the game progressed, 89 per cent of captains who won the toss batted first.

Even the 11 per cent brave enough to field first lost more games (26) than they won (23). Nasser Hussain in 2002 was not the first England captain to be fooled by the Brisbane pitch: Len Hutton infamously elected to bowl first in 1954, resulting in the following Wisden match report:

“Nothing went right for the Englishmen… above everything else the whole course of the game probably turned on the decision of Hutton, after winning the toss, to give Australia first innings. Never before had an England captain taken such a gamble in Australia and certainly never before in a Test match had a side replied with a total of 601 after being sent in to bat.”

Nasser Hussain wins the toss and fields at Brisbane in 2002

Nasser Hussain wins the toss and fields at Brisbane in 2002

Since 1970, though, the advantage of winning the toss has fallen from 40 to 24 runs, and the ratio of captains winning the toss and batting first has fallen from 89 per cent to 66 per cent. Importantly, those captains who have won the toss and bowled first have largely been rewarded for their enterprise (Hussain is a notable exception), winning 179 of those games and losing just 150. Captains who have won the toss and batted first have not been rewarded, winning 319 games and losing 318.

The statistics suggest that bowling first is an under-employed strategy in the modern game. Most of the Test matches with a positive result played since 1970 have been won by the side bowling first (497 out of 966), and yet two-thirds of captains in that period have elected to bat.

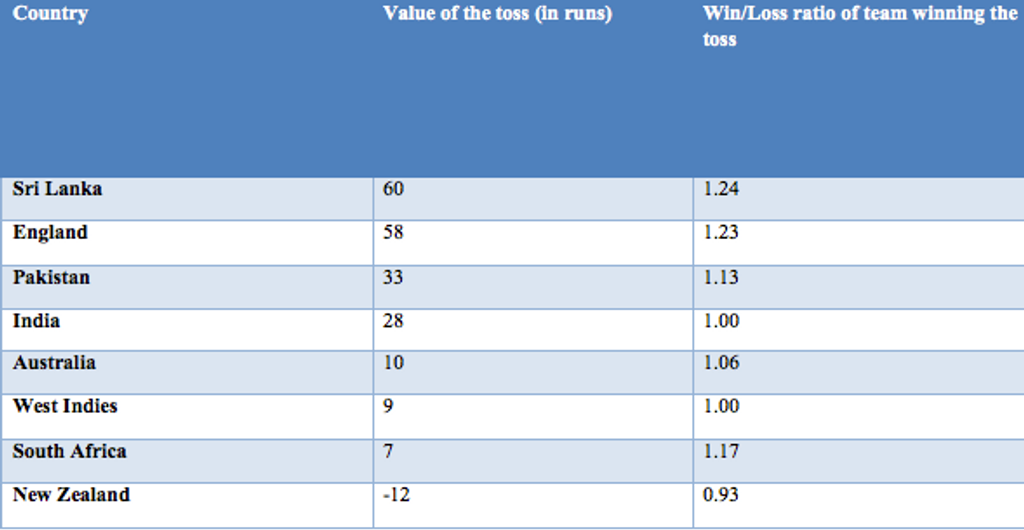

Where, then, is it most important to win the toss? As might be expected, the overall benefit of winning the toss of 24 runs (we’ll take the figure since 1970) varies widely between countries. Intuition suggests that the dry pitches of the subcontinent might be the ones on which winning the toss is most important; indeed, the Asian nations make up three of the top four most “toss-friendly” countries. The big surprise is England, coming in at No.2, where winning the toss has historically been worth 58 runs; there, the toss-winning team are 23 per cent more likely to win the game. The full table is below (qualification: 100 Tests in the country):

There are a couple of interesting quirks to this table – in particular, the fact that extra runs do not translate into a game-winning advantage in India, and the negative toss value in New Zealand, where weather conditions often change quickly. Let’s concentrate, though, on the imbalance that the toss creates in matches in those countries close to the top of the table. Whatever your views on the sentimental value of the toss, it is undeniable that cricket – viewed purely from a game-theoretic point of view – is the weaker for it. The game starts with one side feeling the odds are already tilted against them; this is avoidable.

Shrewd-minded parents across the world have made use of the “you cut, I choose” method for dividing cake among two children. This remarkably simple algorithm ensures that both children believe themselves to have won at least half of the cake, and therefore at least as much as the other child. “You cut, I choose” is an envy-free algorithm: in the cake-eating game, both children feel they have been treated fairly. (For the interested reader, longer envy-free algorithms exist for dividing cake among three and four children; none has yet been found to divide cake among five.)

An equivalent envy-free algorithm exists to start a cricket match, in the form of sealed bids. Both captains submit sealed bids – in runs – to the match referee half an hour before the game. The captain with the higher figure may choose whether to bat or to field first, but the number of runs he submits will be added to the opponent’s score. As a result, both captains consider themselves at an advantage after the bids are announced.

Imagine yourself at Lord’s on 16 July 2015: the first day of the second Ashes Test match. Australia won the first match in a close finish in Cardiff (of course they didn’t, but let’s give them this hypothetical victory), chasing down 248 on the final day with a few overs to spare and four wickets in hand. The rain has stayed away but moisture is in the air; it seems very much a bowler’s day. With the pitch expected to flatten out, Day One could be crucial.

Those fortunate to have been to Lord’s on the first morning of a Test know that early-bird murmur so well; that English expression of mutual expectation over breakfast. Delve into the white noise and you will find thousands of conversations largely focused on who’s playing and what the winner of the toss should do. Both of these subjects provide opportunity for debate; sometimes there are close calls to be made and the murmur will acknowledge both sides of the argument. Neither, though, forces spontaneous debate in the same way that sealed bids would. Even with unchanged teams and a clear advantage to bowling first, sealed bids challenge every member of the early-bird audience to come up with his own figure, to be pitted against those of cricket-lovers and pundits everywhere, and eventually against the numbers bid by the opposing captains.

The strategy can get complex. What you bid is not only a function of what you think the bat-or-field option is worth, but also what you expect your opponent to bid. Let’s assume that, in June 2015, Australian captain Michael Clarke already has a reputation as a low-bidder; he’ll be damned if he’s going to give away runs for free to the Poms. He did, though, in our scenario, win the bid in the first Test by 20 runs to 15. Bowling first at Cardiff for the previous Test turned out to be a shrewd decision, allowing Australia to bowl England out cheaply in the first innings and control the game to victory on the fifth day as batting conditions improved. Alastair Cook, keen to give Jimmy Anderson and Stuart Broad the first crack with a swinging ball this time around, sits in the Lord’s dressing-room and mulls over his options.

How would Alastair Cook and Michael Clarke adapt in this fictional scenario?

How would Alastair Cook and Michael Clarke adapt in this fictional scenario?

He believes fielding first is worth at least an early wicket, which against Australia is somewhere in the region of 45 runs. He also knows that, since 1970, the toss has been worth a mammoth 71 runs on average at Lord’s, with the captain calling correctly having won 59 per cent more Test matches. Most of them, though, batted first and Clarke has never gone any higher than 25 in the bid. For Cook, it would be folly to give away more runs than he needs to. In the end, Cook bids 42 runs, keen to beat away a bid of 40 from Clarke, or a possible bid of 41 designed to beat his own 40 bid.

In the other dressing-room, Clarke has already made up his mind. Maybe it’s a bowling morning, but there are five days to this Test, and all this statistical stuff is pure ivory-tower nonsense. He knows Cook is likely to want to bowl first given the conditions and the result at Cardiff. Clarke bids zero – a strong statement of intent and faith in his batsmen. It has the added benefit of making Cook look foolish for giving away all of those runs for free, when he could have won with a bid of just 1 run. First blood to Australia, who effectively start the game 42 for 0.

Let’s pause here and take a wander around Lord’s. We still have half an hour to go before the start of the match. We know the teams; we know who’s batting first; we knew all along that the winner of the auction would probably bowl. Spectators continue to filter in rapidly through the turnstiles. The murmur intensifies as the start of play approaches; what are they discussing now?

The conversations are still full of debate, in a way they were not in the era of the coin toss. Many believe that Cook has finally lost it, with the award of 42 free runs to the old enemy something abhorrent. Some tentatively agree but are secretly relieved to be bowling first; the air is only getting muggier, and the ball should hoop round corners. A small minority have – like Cook – calculated that 42 runs is only one wicket, and are backing the English bowlers to vindicate the decision by having Australia four down at lunch.

My tale stops here; I shall leave it to the reader to decide whether Anderson and Broad ripped through the Australian top order to leave them 70 for 6 at lunch, or whether a hint of early movement was soon forgotten on the way to dual hundreds from David Warner and Clarke and a closing score of 301 for 3. The important point is that the game has at once been made fairer and more controversial: there is something else to argue about as the first bottle of prosecco is popped open ten minutes after the start of play.

The toss of a coin to decide the start of the game is more than just traditional – it is poetic, and a great leveller. No matter how large the gap between teams, the match starts with an act that brings the captains together in a moment of equal chance and, as the coin falls, the audience watches on in hope. But in an era where many wonder where Test cricket will be in 20 years’ time, we need intrigue and debate, not poetry and tradition. Sealed bids are a rare way of making our great game better while courting the controversy that the sport needs to survive. Perhaps, in 100 years’ time, this new method of starting the game will be seen as just as traditional as the coin toss is today.

Anton Chigurh’s game of chance is ill-suited to cricket, which is, at its heart, chess on grass; a test of skill. The world of modern cricket is no country for old men: let the traditional coin-flip die.

Figures correct up until June 30, 2014

October 21 2019: We have been made aware of a similar proposal – the NBmethod – made by Nagesh Bharadwaj prior to publication of this article. While the author was unaware of this previous proposal, we wish to credit Nagesh’s work. Click here to read his proposal.