John Stern was in Australia to cover the 2014/15 Test series against India when news broke of Phil Hughes’ death. He recounted the aftermath of the tragedy, a sensational, emotional Test match at Hughes’ adopted home in Adelaide and the search for closure as friends and fans attempted to come to terms with the loss.

Published in 2014

Published in 2014

It was time to move on. The last few stragglers were making their way from the Adelaide Oval and across the River Torrens back into the city. Some felt inspired and enriched by one of the great Test match finishes, others by the local Coopers Pale Ale. Just to the right of the main entrance of this swanky and expensively rebuilt stadium, officials from the South Australia Cricket Association (SACA) were packing up the shrine to Phillip Hughes, their adopted son who 18 days earlier had fallen while representing their state.

There had been flowers, bats, pads, gloves, a helmet, even a bottle of Tasmanian lager. There was a book of condolence. These tributes sat beneath an image of Hughes in his Adelaide Strikers T20 shirt, smile beaming out at those who came to observe and pay their respects.

It was an arresting sight. The new Adelaide Oval is an imposing edifice, all shiny, modern and corporate. Then it hits you, these messages from players, fans and cricket-lovers, from all over this vast continent. Yet this shrine was but a small percentage of the global outpouring that greeted the passing of Hughes. The contagion of Twitter yielded the remarkable #putoutyourbats, a photographic symbol of sympathy which spread from Dubbo to Delhi, from Noosa to New York City, where the Australian actor Hugh Jackman placed a bat on the Broadway stage before a performance. At a concert in Munich, Elton John dedicated Don’t Let The Sun Go Down On Me to Hughes.

These waves of emotion culminated in a televised funeral in the broiling afternoon heat of Hughes’ hometown of Macksville in New South Wales. Thousands watched on big screens at the Sydney Cricket Ground and the Adelaide Oval.

Arriving in Adelaide five days before the rescheduled first Test against India, I was unsure what to expect. The mean-spirited Pommie cynic in me had started to baulk at the seemingly bottomless reservoir of sentiment for one tragic individual. There was plenty more to come in the course of the next 10 days. At times it felt like ‘enough now’ but it was also possible to understand why this shocking tragedy should touch so many so deeply and why it will have a lasting impact on Australian cricket.

Some of the 63 bats lining the windows of Cricket Australia’s headquarters. Stay strong @seanabbott77 #PutOutYourBats pic.twitter.com/CwHOOeA1bp

— cricket.com.au (@cricketcomau) November 28, 2014

***

“It was their Diana moment and that’s not a cliché,” says Mark Nicholas, the English face of Channel 9’s cricket coverage in Australia. “The emotion, the compassion, the sentimentality is, I think, pretty easily explained. A man you love dies in a car crash – that’s awful, shocking, a waste, tragic. A man dies because a cricket ball hits him – it’s different because we all relate so closely to the game and it barely seems possible that someone could die because of it. Therefore the sharing of the grief is understandable.”

Nicholas’ assessment of Hughes, the batsman, only exacerbates the excruciating sense of loss for the cricketing public. The country boy, who lived for cattle and batting, had been living Australia’s cricketing dream. “He was a hell of a player,” he says. “I thought the previous group of selectors really got him wrong. Perhaps John Inverarity [former chairman of Australia selectors] was worried that his raw technique might not stand up. He’d have been in this side ahead of Chris Rogers ultimately, and I think he’d have gone on to do great things.”

Keith Bradshaw, the man who used to run Lord’s as secretary of MCC, was Hughes’ boss, the chief executive of the South Australia Cricket Association who signed him from New South Wales two years ago. A former first-class cricketer with Tasmania, Bradshaw has experienced enough pain in his life recently, having had two bouts of bone cancer. Speaking on the eve of the Adelaide Test match, his voice understandably still shakes with emotion. “We’ve been totally gutted and shattered,” Bradshaw says. “We loved him. Everyone loved him. I’ve never experienced anything like it and I hope I never do again. He fitted in really well. He spent a lot of time at coaching clinics and with kids. He always took time to have his photo taken and I’ve had lots of letters from people, with photos of their children with Phillip.”

Amid all the grief in the immediate aftermath of Hughes’ death, Bradshaw and his team at SACA had to reschedule a Test match with a week’s notice. There was a small core of Adelaide patrons who were unhappy with their annual five-day festival being brought forward by three days (and becoming the first Test of the India series). There was an outcry from some SACA members, who, unable to attend on the new dates, could not transfer their membership passes to friends or family. In the circumstances, this seemed to be the sort of small-minded reaction that Bradshaw would have often experienced at Lord’s. He saw the funny side of this comparison.

When it came to the event itself, this unprecedented match charged with emotion, electricity and symbolism at every turn, the naysayers were not heard. Instead of the traditional series-opener in the unforgiving heat of the Gabbatoir, Australian cricket would re-emerge from the darkness in the city of churches. The sporting world is full of meaningless mottos. I noticed in the lead up to the match that the Adelaide Oval’s tagline is ‘The heart of it all’. I’m not sure what that’s supposed to convey on an everyday basis but in this unusual week it seems to have an unintended resonance.

“It’s very fitting that it’s being played here,” Bradshaw said before the Test. “Phillip was loved by everyone here and hopefully it’ll be a very fitting tribute to someone we’re all going to miss. It will be an occasion and the eyes of the world will be on us. It will be a moment in history that we will remember for the rest of our lives.”

***

He wasn’t wrong. From the moment that Australia’s players reconnected with their sport on an Adelaide club ground three days before the Test, the whole event was compulsive viewing on every level. David Warner, a teammate and close friend of Hughes, withdrew from the first practice session to be counselled by the team psychologist, Michael Lloyd. Coach Darren Lehmann said he wanted “normal Test cricket”. Shane Watson admitted to apprehension when going into to the nets for the first time.

The following day bouncers were bowled in the nets and Brad Haddin became the first player to speak formally on behalf of the team since Michael Clarke’s remarkable funeral address. Arms folded, leaning on the table, eyes reddened, his words were sparing and tart. In normal circumstances it would have felt like he was being uncooperative but not on this occasion. He was just getting through it. He was asked if the tragedy had united Australian cricket. He paused for thought and said: “I… I don’t really have an answer for that.”

Watson spoke more expressively, his voice wavering more than once. Then the day before the Test, when the captain usually gives a press conference, Mitchell Johnson appeared. Clarke had been spared this ordeal. In a stage-managed start to proceedings, Johnson was asked whether he could reveal the team for the Test. He took a breath, smiled and said: “I’m actually quite nervous. Josh Hazlewood misses out, Shaun Marsh misses out and Phillip Hughes is our 13th.”

For two days, as balls were hit, limbs stretched and bravado displayed, it felt like normal service had resumed. But Johnson’s hurried utterance brought it home yet again that this would be no normal Test. This was Phillip Hughes’ Test.

Cricketers the length and breadth of Australia had already paid their own tributes. One club player made 37 and walked off, saying he was completing Hughes’ century. The score of 63 became the new ‘retiring’ score for junior cricket. Black armbands had been worn, 63 seconds’ silences had been observed, teams of all ages and abilities had bonded more strongly than ever.

And now, on an international stage, it was time for Hughes’ colleagues, some of whom had been on the field when he fell, to bare their souls and channel his spirit. The front page of the Adelaide Advertiser on the first morning of the Test carried a full-page picture of Hughes, accompanied by the words ‘We must play on’ and a green border on which were printed dozens of tributes from fans.

The two teams line-up before the start of the Adelaide Test

The two teams line-up before the start of the Adelaide Test

There were many uncertainties. Would the pre-match tributes be solemn, respectful and appropriate, or mawkish and cheesy? How would the Aussie players cope diving straight into a Test after what would surely be an emotionally overwhelming preamble? Who would bowl the first bouncer, when would they bowl it and what would the repercussions be?

The bit that got me on the first morning was the playing of the Australian national anthem, which had followed hard on the heels of a brief but beautifully voiced tribute by Richie Benaud that finished with the words: “Forever… Rest in peace, son.” That was also the bit, we would learn later, that got Warner. He was emotional too when he reached 63 and when he made a barnstorming first-day hundred, he buried his head in Michael Clarke’s shoulder.

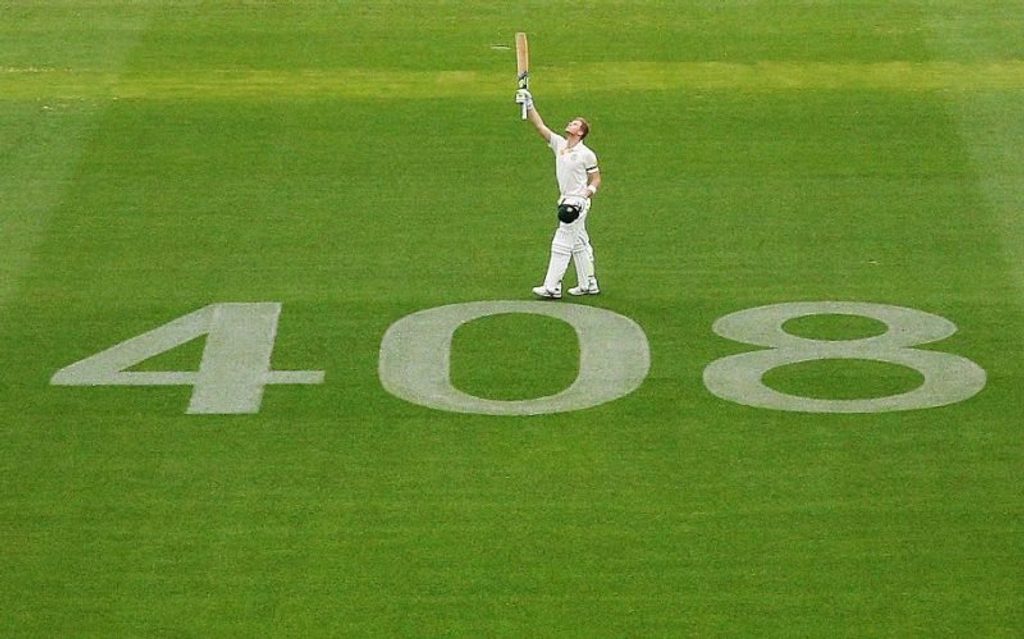

There were so many weirdly magical moments in the match. It was enough to turn someone into a numerologist. Three New South Welshmen made hundreds – the first time ever an Australian Test innings had contained three century-makers from the same state. That they were all close friends of Hughes, whose home state was NSW, seemed more than a coincidence. Reaching 63 took on a symbolism that has a feel of permanence for Australian cricket. When Steve Smith made a first-innings hundred he walked over to the 408 (Hughes’ Test cap number) painted on the outfield, pointed his bat at it and raised it skywards. Bowlers patted the specially embroidered 408 on their shirts, Peter Siddle kissed his black armband, Nathan Lyon raised the ball to the heavens after taking a five-for.

Sentiment fatigue set in once or twice, not least when Warner, in his second press conference of the match, started saying that 63 felt like an unlucky score and how he wanted to get off it quickly. Everything had got a bit weird. But the crowd’s spontaneous response to these new milestones was so uplifting, the relationship between them and the players so unusually close, it was impossible not to be moved.

Steve Smith pays tribute to Phil Hughes after completing his hundred

Steve Smith pays tribute to Phil Hughes after completing his hundred

***

It took 19 balls for Varun Aaron, the man who spoiled Stuart Broad’s good looks at Old Trafford in August, to bowl a bouncer. It was decent enough without being dangerous. Warner avoided it comfortably enough. There was an ‘oooh’ in the crowd, then applause and then cheers. This was what Ricky Ponting meant when he wrote before the Test that he wanted the first ball of the match to be a bouncer to “clear the air”. The game was on and there would be no holding back.

Fifteen minutes later, 800 miles away in Sydney, Sean Abbott, whose bouncer had felled Hughes, bowled a bouncer against Queensland. He would later take a career-best 6-14 to lead New South Wales to victory.

But just before lunch on day three, Virat Kohli ducked into a Johnson bouncer first ball and was hit on the badge of his helmet. The batsman was the man on the field who appeared least bothered. Players and umpires rushed from all sides and Johnson was clearly shaken up as he walked back to his mark while being comforted by his captain. It was another step on the road back to normality.

At the end of a pulsating Test, both captains used the phrase “no regrets” but for different reasons. Michael Clarke had jeopardised the rest of his career by playing in the first place while carrying a hamstring injury, then by batting on after aggravating his long-standing back injury and tearing his other hamstring. “It was the most important Test of my career,” he said. Kohli, in his first Test as captain, had batted like a warrior prince, carrying his team with a century in each innings and pursuing a run-chase with an unblinking belief that belonged to another era. No regrets. This match was fortunate to have Kohli leading India. They lost but they may have discovered a spirit of adventure that can serve them and the five-day game very well indeed.

The one on-field flare-up on day four – sparked inevitably by Warner when he was recalled after being bowled off a no-ball – did not dilute the spirit in which this match was played. There was nothing half-hearted about the play. If anything, the opposite was true. Trifling off-field agendas or petty grievances were sidelined and the only concern was the game. Play hard, play to win, give it a damn good go. It would be naïve to think that international cricket is suddenly a game devoid of animosity and negativity but there is reason to hope that, as Mark Nicholas says, “the spirit of the game should be the spirit of Phil Hughes”.

The crowd figures at the Adelaide Oval were large, despite the rescheduling, and Channel 9 crowed about their TV ratings. There was a sense that this tragedy had rebooted Australian cricket and reconnected the public with cricket as a game, not just a job or a multi-million dollar business.

“I hope that it means nothing more than a little reining in of attitudes and priorities,” says Nicholas. “At large I think the modern sportsman has become very selfish and I certainly think that in Australia there has been an ugly side, at times, to the cricket. For me, the spirit of cricket is about respect – for your opponent and for the game. That’s all. If it brings it back to that, if it rationalises things a bit, that’s something good that can come out of it.”

***

The flowers have gone now and the fierce Adelaide sun has set. But Australia’s players are still out on the Oval. They are huddled, arms round shoulders, standing on the painted 408, the number of their “little mate”. There is a moment of quiet reflection, a few meaningful words and then an explosion of guttural blokeishness, as Nathan Lyon leads the raucous singing of their victory song, Under the Southern Cross I Stand. And the hot, night air in the city of churches is punctured with “Australia, you f***in’ beauty”. It was time to move on.