Mitchell Johnson experienced the lowest of lows and the highest of highs over the course of his career. In 2017, he spoke to Geoff Lemon about how he rediscovered his hunger for the game on the way to decimating England in the 2013/14 Ashes.

This first appeared in issue 149 of All Out Cricket.

“Your mind’s very clear and it just happens,” he says. “You feel free, and the ball comes out easy. You can finish a game and come off the field and you don’t feel the aches and pains as much. When it starts, you go with it. It’s very rare when it does happen like that. I guess you’re sort of fighting it through your career, trying to get that moment.

“It comes out fast, too, because your whole body is relaxed. Cricket bowling is like a catapult. Your front leg plants and that front arm pulls everything through. Your bowling arm needs to be really loose. It’s a great feeling when you get it, you just feel free in your mind.”

Mitchell Johnson is talking about speed. The pure, unadulterated stuff, not the cut-down version that a thousand would-be tough guys dish out at club and county grounds of a weekend. Not respectable pace, not brisk, not decent enough at first-class level. True pace, the kind that upends even the split-second timing and decades of muscle memory of the very best batsmen.

“It’s a great feeling when you get it, you just feel free in your mind”

“It’s a great feeling when you get it, you just feel free in your mind”

There were days when Johnson had it. And as he describes it, many more when he didn’t. A man who pursued an elusive dream through a thousand nights, occasionally plunging through the surface of sleep into its depths. A Mustang stuck in traffic longing for a highway.

When he found it, he was untouchable, the most menacing in the world. Low-shouldered, more muscle than room to contain it, that particular prowl with which he traversed the field. In profile his run-up was cartoonish, paws tucked up and alternately bobbing, Gargamel chasing a Smurf. But the less common angle from the batsman’s perspective morphed Sylvester into a panther. Teleport to the middle and any laugh would die in your throat. Your throat was the target, the ball exploding from the pitch with mute hostility.

Other times he lost it and fell apart. The evident fragilities, the enigmatic performances, became part of a show that fascinated and frustrated. Few cricketers copped quite the pile-on from opposing supporters and the backlash from their own. In this context, Johnson’s autobiography is actually a worthy addition to a stale genre because of the insight it gives into that conflict. With his persistence and eventual success, he has earned the title: Resilient.

***

One of the most interesting revelations is how much Johnson was an accidental cricketer. A knockabout kid from Townsville, little money and a disjointed home life, moving between relatives, never settled. It’s an entirely normal Australian story, but in contrast to the usual suburban tale of those in the talent pathways. He got into cricket late and by accident to spend time with friends, and stayed because his club insisted. Someone had a good eye: they sent him to the bowling camp where he fluked a sighting from Dennis Lillee. Suddenly he was an accidental Academy player, then state, then international, and soon enough leading an inexperienced attack.

Even by then, Johnson knew little about his bowling action or approach. So when things fell apart on the Ashes tour of 2009, he had no answers. “In England I had a lot of people come and say, ‘You need to be doing this, your back leg’s doing that, here’s the footage,’ and to me the footage looked exactly the same. It was just an overload. I needed to have my own space and talk to the people who knew me best.”

Lillee remained one of them. But he wasn’t often around, and Johnson struggled to put improvements into practice. “When you’re in that bubble it’s really hard. You know there are things you need to work on but you just don’t have the time. You’re going from one hotel to the next. You can’t do it in a game, because you haven’t practised it.”

In the meantime, his good days and Australia’s limited bowling stocks meant he just kept being picked. The three years before his foot gave out in Johannesburg in 2011 saw Johnson pull on an Australia shirt for 34 Tests, 65 one-day internationals, and 20 T20s. The grind did what grinding does. “I did fall out of love with cricket,” he says. “You are playing for your country, but it becomes like a job. When I had that toe injury, I was looking forward to something breaking at the time. It felt like a blessing in disguise. I was able to get away from the game, and I didn’t miss it at first, but then I started to get that hunger back.”

This applies across various walks of life: a dilemma in which being at the top of your field denies you the chance to improve or maintain your standard. Johnson felt his strength and fitness had suffered, and took to a gym frequented by SAS soldiers. He also resolved to sort his head out. “I was able to actually fix problems,” he says of the time out, “whether a little technical thing or a mental thing. Most of the time it is mental. I was up and down through the early parts of my career. I didn’t know how to keep aggression but not go overboard, and body language is huge. If I didn’t bowl exactly the ball that I wanted you could see it in my body language.”

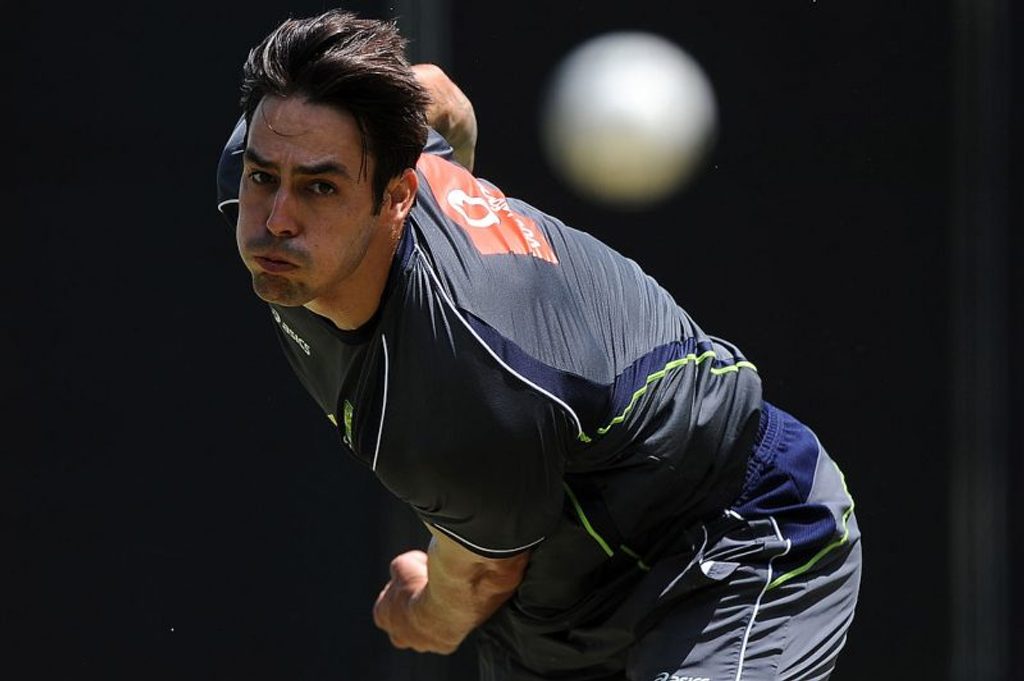

Mitchell Johnson lets loose in the nets

Mitchell Johnson lets loose in the nets

“I met [the boxer] Danny Green, and he’s got people trying to knock his head off, and the SAS guys, what they have to go through – I don’t compare war and sport, but knowing what their mental capacity is, it’s incredible. All we do is we play a game of cricket.”

He played a couple of decent Tests against a modest Sri Lankan side in 2012/13 and toured India as a back-up bowler, but had fallen back in the pack. Instead of Tests he went to the IPL, where in somewhat unlikely fashion everything clicked.

“Twenty20 in my international career was something I didn’t enjoy as much because I felt like it could take you out of your rhythm,” he says now. “But funnily enough, I had a really good season with Mumbai. I was swinging the ball at pace, I was one of the leading wicket-takers. That was huge for me, it was good to get out there and just bowl fast. That might have been a sign as well that bowling me in short spells was the best option.”

***

And so to the 2013/14 Ashes in Australia, which a few English readers might recall. Johnson’s book starts in Brisbane, with him preparing to bowl. “The top of my mark, I was still quite nervous, and the first over I couldn’t breathe,” he says now. “It felt like it was my first Test again, in a lot of ways. But I also felt like I was more ready. I’d missed out on the Ashes tour in England just before that, and I think that was a good thing because I wasn’t ready at that stage.

“The first three overs didn’t go to plan, but I had my tail up as soon as Trott came in. I’d been taken off, and I said, ‘Come on, this is a chance here.’ I got an over in, bowled a couple of short balls and got him down the leg-side. That got me up and going as we went into the break, and it started to feel really good again.”

I watched that summer’s carnage from behind the arm, and wrote on the Adelaide episode in these pages. There was a moment, midway through the balletic violence of that first-innings 7-40, when WCM editor-in-chief Phil Walker leaned over to say, “You realise you’re watching one of the great Ashes spells.”

Mitchell Johnson sends Alastair Cook on his way in Adelaide

Mitchell Johnson sends Alastair Cook on his way in Adelaide

Johnson (spoiler alert) also remembers that day fondly. “It’s in my top three, I reckon. Playing at the Adelaide Oval which doesn’t assist the quicks too much, coming from Brisbane. I was told I wasn’t hitting the stumps in the first Test by a former player on Twitter. So that fired me up a bit.

“My lines were really good, I felt like I had control, I was bowling straight, used the reverse swing when it came in, bowled my short ball on a wicket that didn’t bounce a lot. Had my best mate there celebrating his birthday. I came off and had a couple of tears in my eyes. The boys told me to lead them off, and I was quite emotional because a lot had gone on through my career, and it sort of just all came out. It definitely felt special.”

His momentum saw Australia roll through the series. A tired England team had been cracked with the first blow, and Australia’s strike bowler who had always been seen as unreliable was suddenly irresistible. By the fifth win in Sydney, the fullest possible catharsis was complete.

“I was absolutely cooked at the end of it,” Johnson says of greeting the result. “I was shattered. I could barely keep my eyes open trying to celebrate. I felt like it was an awesome achievement: that’s in history, one of the great results for Australia. I was there for the other 5-0 as 12th man, but to take that team and then compare it to ours…”

Johnson never looked fragile after that, even when he wasn’t dominant. He was content in his abilities. Perhaps, behind that newfound steadiness and resolve, behind that Ashes series and its lead-up, was something simple. “I started to really enjoy my cricket again. Bowled the way I wanted: bowl fast, bowl my bouncers, don’t worry about trying line and length. That’s not me. I’m not Glenn McGrath, I’m not somebody else, I’m just me, I’m a slingy bowler, just accept it. And that’s what I did.”

Sound advice for anyone. These days Johnson presents as a much more content and balanced character. Though just as his early career seemed to involve two bowlers, he still has contradictions. Johnson has spoken of being a private person, and writes in his book about the gulf in communication between Australian men, including his father and some teammates. Yet, both in that book and in this interview, this man is honest and direct about his struggles. For him at least, things are different now.

“We just don’t talk as males, I guess. It was a bit of an eye-opener actually, at the end of my career, I opened up about a few things and some of the younger guys were like, ‘Oh yeah, we’re going through the same sort of thing.’ That’s an issue that we have in society anyway. Walking down the street, you don’t know what the person across from you is going through.

“I find that I’m a lot more open now. I can talk about things and get it out there and not bottle things up. I feel better for it, a hundred per cent. That’s something a few of us tried to do more of at the end of our careers. Whether it’s sitting down at dinnertime or whatever it is, just talking and getting things off your chest.

“I’ve definitely had my ups and downs, being retired. You come off it, I guess? I was really on a high for a while after I finished. Then I hit a bit of a low, I probably missed that structure.”

***

It’s no surprise, then, that Johnson is contributing time to the depression charity Not Alone, speaking eloquently on some of their online videos. That’s one part of a busy life in Western Australia. He’s getting into craft brewing, building a bowling app, raising his family. “Cricket’s much easier,” he laughs. “We’ve got two kids and it’s hard work. I love seeing Leo grow up, I missed a lot of that with Rubika, she’s four now. She understands a lot of things, she’s clever. We bought her rollerskates today, and she’s trying to do jumps on them already.”

For his own adrenaline fix, there’s also the small matter of fronting sold-out WACA crowds to play Big Bash for the Perth Scorchers. Johnson has done his bit, taking 3-3 from four fiery overs in a semi-final victory over Melbourne Stars. It was Scorchers coach Justin Langer who drew Johnson back into the game. “Originally I wasn’t sure after retiring. I thought, how much is it going to take out of me? The way JL put it to me, he said, ‘We just want you to have fun, mate, and if you’re ready to go at the start of the season that’s perfect.’

“I’m enjoying it now. It makes me think about next season. I might go around again. There’s been a few offers coming in from different leagues, I almost feel like that specialist. I didn’t need to do the old training that I did, which was a lot of running, a lot of weights, a lot of bowling, just a lot of volume. With T20 it’s just about getting rhythm and staying fresh.”

It’s interesting trying to imagine Johnson becoming a dotage player. He says repeatedly in the book that all he ever wanted to do in cricket was bowl fast. Currently he’s still clocking 145 kilometres per hour (90mph), and has some time left. But could someone who was all about velocity cope with deceleration? “I could be someone who doesn’t bowl as quick, but that’s how I get wickets as well. It’s an intimidation factor. Whatever team picks me up, they’ve got to tell me what they’re expecting. If I can still go out there and bowl fast then that’s what I’ll do, and I think most teams would want me to bowl fast.”

Mitchell Johnson played his final Test in November 2015

Mitchell Johnson played his final Test in November 2015

He speaks of how quickly he got the taste again, of how being hit over his head for six was enough to fire up the yap and the glare and the want to bowl faster. Johnson is only 35 years old. His burnout in 2011 was close to repeating when he retired in late 2015, the schedule again the culprit. He was a surprise cricketer, and looking back over his story, it increasingly seems like no one quite knew what to do with him when he arrived. It also makes you wonder whether he might have done more, played longer, had he been managed with a bit more awareness.

The physical prowess is still there, and the competitive urge burns still. At least a glimmer. “When I heard that Nathan Lyon had said that Mitch Johnson could consider coming back playing T20 Internationals, my ears did prick up at the time,” he admits. “But then I thought – I know what it’s like at that level, and the stresses that come with it, and I’ve done that. I’m done with it. There are better players out there that deserve it, they can go through it now.”