He sat down with Wisden Cricket Monthly editor-in-chief Phil Walker to discuss hitting Ponting, bouncing Lara, supporting Fred, the “golden age” of ’04 to ’06, and how he survived being simultaneously on top of the world and on the floor.

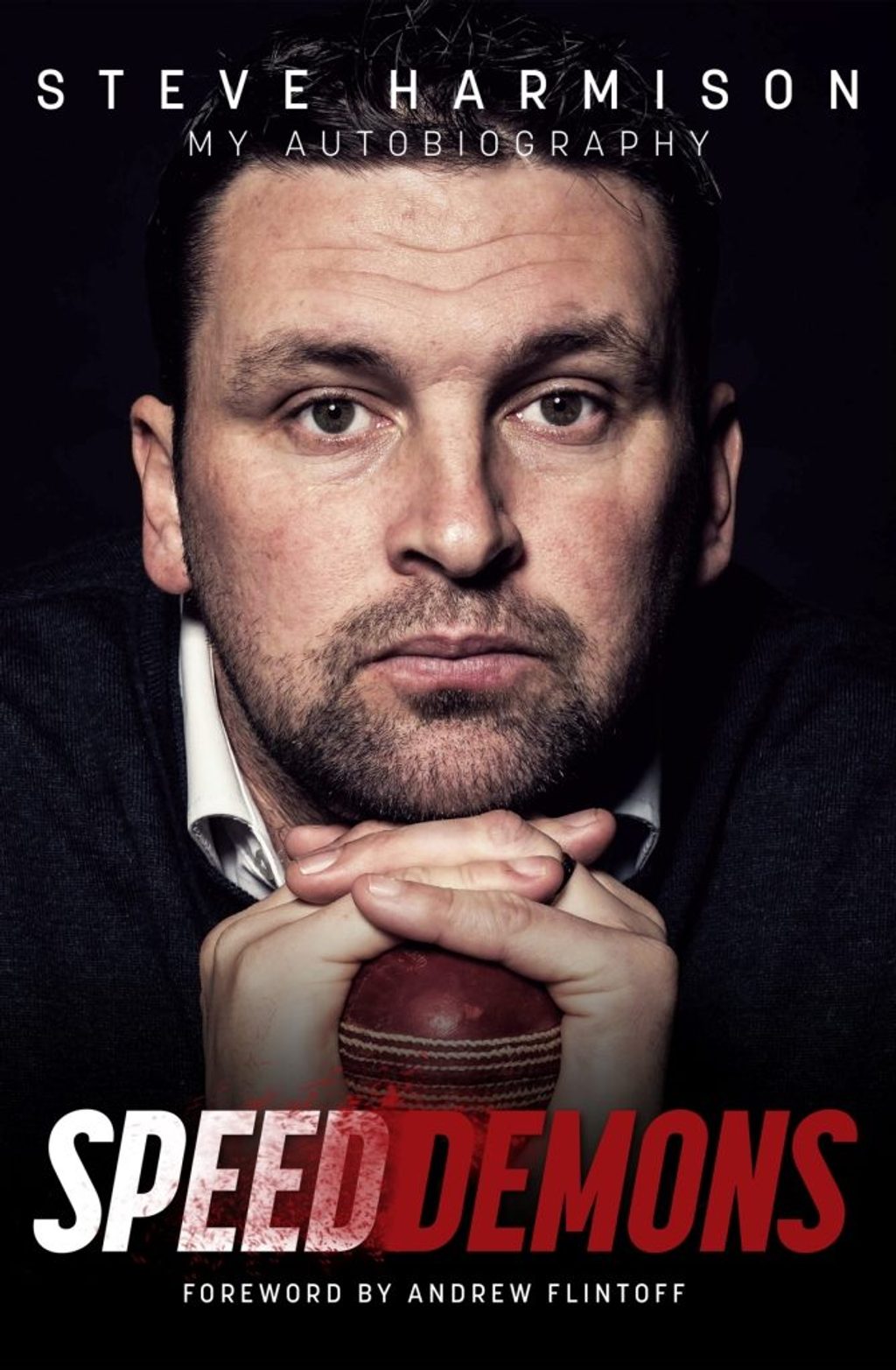

Speed Demons is out now, published by Trinity Mirror Sport Media, available for £20

In 2004, Stephen Harmison was 25, playing for England in the same team as his best mate, earning good money, happily married, and recognised as the best exponent of his job in the world. And he felt dreadful.

At The Oval in 2004, the England team stood on the verge of a staggering tenth Test win of the calendar year. Their opponents, the West Indies of Gayle, Lara and Chanderpaul, had already taken six of those beatings. England batted first, a boy called Ian Bell made 70 on debut against a pumped-up Fidel Edwards, and by lunch on day two they’d got up to 470.

By mid-afternoon, it was over to the bowlers. To peak Hoggard, pounding Flintoff and the promise of Jimmy Anderson. Things were happening fast by this stage, and for all the handfuls of signposts staked along the road, 2004 still felt like a sudden and seismic acceleration. English cricket fans, for the first time in 20 years, were enjoying a summer-long showcase of Ashes-readiness.

In 55 overs that day across two brutalised Windies innings – the tourists having followed-on to finish two-down at the close – 10 wickets would be taken by England’s quicks. But they didn’t fall to Flintoff or Hoggard, who at least managed one apiece, nor to Anderson, who went wicketless. Not that it mattered, because the gaggle of arms and legs who’d got things rolling that year with a spell of seven wickets for 12 at Sabina Park, Jamaica, had already decided to finish the job himself.

Harmison was the first England bowler since Botham to be ranked as the best in the world

Harmison was the first England bowler since Botham to be ranked as the best in the world

Stephen Harmison’s eight wickets that afternoon – six in the first innings, two in the second – took his tally to 102 from 23 Tests to cement his position as the No.1 ranked bowler in the world. It was not hard to see why. Six-and-a-half feet of lissome menace, styled in the vein of the great wordless West Indians yet filtered through Ashington, a proud, once-thriving pit village in the north of England with a tasty sideline in world-beating sportsmen. He was quick that day. Searingly quick. Even Lara was out hooking; it was on him too fast. Back then, that went for everyone.

Harmison was 25, playing for England, earning good money, and recognised as the best fast bowler in the world. And he was in bits.

Now, aged 38 and five years retired, Harmison has decided to get it all down on the page. Of that match at The Oval and its surrounding noise, he writes: “I would have to lie down in the dressing room to help ease the churning in my stomach. I was masking my true problem by saying I had a bad back and I needed to stretch it. Sometimes I’d lie on my front and push my back up. I’d be complaining it was stiff, but all I was doing was trying to ease the awful sensations I was feeling. It worked in that it helped me get through those periods when mentally, physically, and literally, I was on the floor. But it was no solution.”

In English cricket circles Harmison is both hugely popular and famously unreachable. When we do finally track him down after a handful of aborted missions and missed calls, he is as expansive and open as ever. We talk for well over an hour. He has much to say.

Harmison’s new book is frank and candid

Harmison’s new book is frank and candid

Why choose to write the book now?

Well, firstly it was an enjoyable process. It was hard going over old ground, but I thought it was quite therapeutic. It made me feel a lot better about myself, with what I achieved in the end. It was good to reflect on that. The book highlights that you can suffer, but also succeed as well.

That Oval match in 2004 that you talk about in the book – what was it was like to be on top of the world and, at the same time, literally on the floor?

It’s difficult… Cricket was my release – I struggled when I was in my own head. That was quite scary. But when you’re out in the middle and you’re bowling – especially when you’re doing well – you just want to be bowling. The more I bowled, the more I could put the other stuff to one side. My focus on the game would improve, there was no room for these negative thoughts circulating around my head. My game was in such a place that I was basically in cruise control. I just had to turn up and put me boots on. I had programmed my body to bowl a certain way, the dynamics of my bowling action at the time were perfect. I didn’t need to think about it. I just had to ensure that I controlled my emotions, trying to be the best that I could be when I had the ball in my hand. But when I was away from the game, other aspects became increasingly difficult for me.

So cricket was your separation?

It was, yeah. It was somewhere where I could go, knowing that they couldn’t get to me. Nothing could get to me. Team-wise we were in a great place, and individually I was in a decent spot meself. From that aspect, it was a release. As soon as I stepped on that pitch, my troubles just seemed to go away.

Glory days: Harmy, Rob Key and Andrew Flintoff celebrate in ’04

Glory days: Harmy, Rob Key and Andrew Flintoff celebrate in ’04

You debuted for England in 2002 as a kid, and within two years you were the No.1 bowler in the world. And yet you write in the book that cricket was by no means an obsession and if anything you fell into a career by accident. How were you able to process all of this happening so quickly?

I just had to go with it. I would never say that cricket was an obsession from my first day at Durham until the final ball of my career. I viewed cricket as my job. I worked in the game, I never saw it as a sport that I’m playing which I love. However, I really did love bowling. That’s one of the only aspects that I truly loved. It was never an obsession and I began to resent it towards the latter stages of my career. My body was in such bad shape it forced me to give up the sport. People ask me now: Do you miss it? No, I don’t miss it. I miss being around the game, and being around the people, but the game itself I don’t.

What made you so good between 2004-2006?

My team, simple as that. When you’re around good players your game seems to come more freely. There were no egos in the dressing room. The seamers wouldn’t be discussing who’d got the individual wickets, it would always be, ‘How are we going to get 20 wickets between us?’ That’s why England were successful then and why I was successful as a strike bowler. If you look at it, we all got five-wicket hauls in key series. Over the two years I got the credit and I’m grateful that I was regarded so highly. It was the team though – if we were all bowling well, we knew that no batsman was getting away.

Was there a moment during that period when you knew you were on to something special?

We didn’t know how to get beat. The third Test against West Indies at Old Trafford in the 2004 series is a prime example. We were chasing 231 and we were two wickets down and only 27 runs on the board. Vaughan was dismissed and we were three down on a bowler-friendly pitch needing a further 120 runs for victory. And the West Indies were bowling rapid. Hostile. What the public don’t know was that Graham Thorpe was in hospital, he’d had an injection and passed out. He wasn’t going to be able to bat for us, so we were effectively four down. But we simply didn’t know how to get beat. Fred and Keysy [Rob Key] saw us home. It was that moment that I knew we were on to something special.

I believe when Nasser got the job [as England captain] that was the turning point for English cricket

Do you think, a decade on, that we are living with the legacy of that era?

I think a lot of it’s down to Nasser [Hussain]. He took the national side by the scruff of the neck and gave the youngsters a chance. He brought us on tour, we were ruthless and our games developed at a rapid rate. He wasn’t bothered whether he was liked or not. You could argue that the ‘golden era’ of ’04 to ’06 was down to Nasser, he gave us the opportunity that just wasn’t offered in the past. I believe when Nasser got the job [as England captain] that was the turning point for English cricket.

***

Six months on from The Oval match against Lara’s Windies, Harmison was at Heathrow airport preparing to fly to South Africa. A huge year lay out in front of him. But the prospect of touring – of being away from the securing presences of his family life – had brought on an acute sense of anxiety ever since his first overseas trip to Pakistan with Flintoff’s England Under 19s team.

Of Heathrow that day, Harmison writes: “Have you ever tried to tell a five-year-old that daddy’s not going to be home for weeks on end? At that moment I really wish I wasn’t a cricketer. I really wish I’d stayed working in the factory with my dad. This feels like the worst day I’ve ever had. Walking through Heathrow, I’m in a daze, but it’s not far off Christmas and I can tell other people are happy. They’re going places they want to go. They’re probably going off to see their families.”

You talk about saying to yourself at Heathrow, over and over again, “I’m not giving in, I’m not giving in”. It’s a recurring theme throughout the book.

I never knew how to. I know people think that I didn’t fulfil my career potential but I know that I never gave in. There were plenty of opportunities for me to do so, but I made sure that never happened. If anyone is suffering with similar issues, I always make myself available for support. I don’t think there’s an issue that a cricketer can go through that I haven’t experienced, I’m always at hand. It wasn’t just with the South Africa tour, it was every tour. I knew that I was never going to give in. The area I’m from, the North East, we don’t give in.

Harmy draws blood on day one of the ’05 Ashes

Harmy draws blood on day one of the ’05 Ashes

Did you talk to people close around you?

When you feel that bad, it doesn’t matter who you talk to. There’s only one person suffering, you. I used to write things down to make me feel better. I spent a lot of time with Keysy, we shared a room and he would listen. But at the end of the day, they couldn’t do anything, I would try to go somewhere to get away from it, but it never worked. You don’t suffer in silence, but you suffer on your own. You must work out for yourself the natural progression of getting out of a negative mindset and into a more positive atmosphere.

Do you think there’s something innate about cricket that makes many people who play it professionally vulnerable to mental health issues?

I think it’s a hard one to blame on the game. There are individuals who are prone to having chemical imbalances in their bodies before coming into the game. A lot of the negative thoughts come when you’re by yourself. I don’t believe cricket is a team game, it’s an individual sport that is played by 11 people. It’s good to have team plans and strategies, but essentially, it all comes down to if that person bats well or that person bowls well. The mind is a cruel thing – at times, if someone’s balance is not right, that’s when cricket makes them susceptible to mental health issues.

I don’t think Ponting has ever been hit in the head – he was hit in the head. Hayden doesn’t get hit in the head – he was in hit in the head. The question could be flipped, were the Australians nervous?

Let’s go back to Lord’s, day one of the 2005 Ashes. Were you nervous, anxious, before climbing into Langer and Ponting?

I felt nervous before every Test match, but that’s natural. I’ve always said the difference between nerves and excitement is whether you’re smiling or not. You back your preparation, and the preparation for me going into ’05 was unbelievable. The one-day series was great; I played four games for Durham and got 30 wickets; Everything was positive in my game, I felt fit, I felt strong. I was bowling short because that was the plan. Hoggy was getting plenty of swing from the other end but I wasn’t a natural swinger of the ball, so I kept peppering them with the shorter ball. The batsmen would stop moving their feet because of the short ball, and when it’s swinging you’re susceptible to being caught behind the wicket. Had we planned to be aggressive? Not really. We were aggressive because the ball was swinging. I don’t think Ponting has ever been hit in the head – he was hit in the head. Hayden doesn’t get hit in the head – he was hit in the head. The question could be flipped, were the Australians nervous?

You said earlier some people think you didn’t fulfil your potential. Is that your opinion?

No, not one bit. Whatever people thought about the career I had I couldn’t care, I was happy with what I’d done. I enjoyed playing with the people I played with, and I put the best I possibly could in every single time, and whether it was good enough or not, I always knew I could sleep well at night knowing I’ve tried my best. It was always questioned throughout my career, whether I wanted to play cricket for England, whether I wanted to tour, the ‘homesickness’ problems were continuously brought up, but I was happy with them saying that, because there was more to it.

So that ‘homesickness’ euphemism that the England management fell back on was a necessary shield?

It was like putting an Elastoplast over where you should have put stitches. There was so much going on that I couldn’t let out and that I didn’t want to let out because I’ve seen what happened to two or three people where the minute you mention it, if you have one bad game you’re finished and you don’t play again. How I finished was brilliant. That Oval lap of honour in 2009 was muted compared to 2005, but me and Fred walked round very slowly. It was one of my most enjoyable moments walking off that pitch, because I knew that was me done, and the next chapter of my life was starting. We wanted to soak it all in, but we were both relieved.

Do you have a picture for your life over the next couple of years?

It’s basically a day by day thing. I’ve really enjoyed doing the commentary, I haven’t done as much TV as I would have liked but hopefully that’s still yet to come. I really do enjoy talking about the game, I love watching these players play well and to talk about when they’re playing well. The game still gives me a lot of pleasure.