Shannon Gill talks to an Australian icon about the summer his cult-hero status was forged.

“The problem with Merv Hughes… is that he thinks he’s a fast bowler.”

Ian Chappell’s assessment of Merv Hughes’ early forays into Test cricket was blunt, but hardly harsh.

His debut against India in 1985 returned one wicket at a high price. In his first Ashes Test he was embarrassed by a Botham assault and made a pair in a seven-wicket defeat.

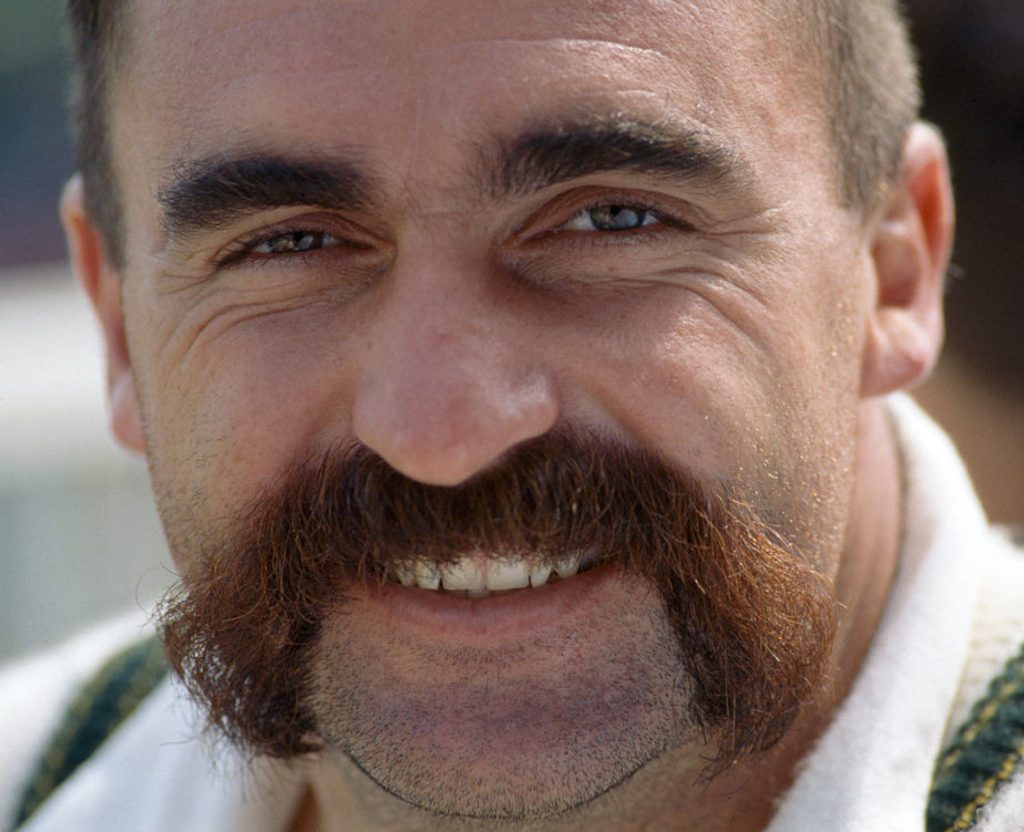

In an era where pace ruled the world, the Hughes macho show – handlebar moustache and the rest – had fallen flat, just 21 wickets at 37 in seven Tests. His Australia captain Allan Border was forced to issue a public ultimatum: “If he’s going to be fair dinkum he should look at this [weight problem] very closely… He’s got a long, long way to go.”

Hughes’ weight came in for criticism

Hughes’ weight came in for criticism

It’s a measure of the man how Hughes responded to such severe criticism from his captain. “Border came out and had a crack, and the media came to me as if it was shock, horror,” he tells Wisden now.

“But AB spoke to me the night before and told me what he was going to say, so I knew it was on the table. AB was the boss and if your boss tells you to do something and you want to hang around, you better do it. That was a kick in the backside.

“Going into 88-89, in the back of mind I knew I had to perform. I was 27,28 and if you’re not in the side regularly by then it’s just about over… I was viewing the start of the 88-89 as a last chance really, to get into the side make a statement and be a consistent member of an Australian team.”

It was a summer that would change Hughes’ life, and re-endear the Australian team to the public. Perhaps it even paved the way for 20 years of world dominance.

***

The marquee event of the summer was the visit of the West Indies, supposedly a side on the decline. Instead, Curtly Ambrose, Malcolm Marshall and Courtney Walsh blew away a Hughes-less Australia in the first game of the series.

Hughes was reinstated for the second Test in Perth, and while the loss of 10 kilograms and his mullet – the moustache remained intact – suggested he’d heeded Border’s words, those in the media remained unconvinced.

“Hughes’ selection was more surprising as he has failed almost every time he has been elevated from Sheffield Shield ranks,” wrote Trevor Grant in the Sydney Morning Herald. “His rampant bull routine has never impressed Test batsman as easily as it has State players.”

No-one was more surprised at his inclusion than Hughes himself, who had been readying himself for 12th man duties, and he reaped the benefits of a build-up free from pressure. “AB came in minutes before we went out to say I was in and Craig McDermott was 12th man. I didn’t have the tension or the sleepless night before and that may have done something for me, it loosened me up.”

“The problem with Merv Hughes is… he thinks he’s a fast bowler”

“The problem with Merv Hughes is… he thinks he’s a fast bowler”

Dropped catches and Viv Richards ensured Australia chased leather, but Hughes got five wickets. Then, in the second innings, something clicked, or rather cracked. Geoff Lawson was felled by an Ambrose short ball, and while his broken jaw was a painful reminder of a team that was bringing a knife to a gunfight, it also served to bring Hughes to boiling point.

“Emotions were high,” Hughes says. “I didn’t think the boys had played that badly in Brisbane, but when we got to Perth and that happened… beforehand it had been just nice against the West Indies. When Lawson got hit it triggered a reaction in me.”

It was some reaction. Hughes struck with his first ball, pinning Gordon Greenidge in front to claim an unheralded hat-trick spread across three overs. He ended with second-innings figures of 8/87, set against 1/239 taken by the rest of the attack.

“I’m looking around at Steve Waugh, Tony Dodemaide and Tim May and thought, ‘I’m a fair chance to take the new ball here’,” he says. “If Geoff Lawson hadn’t have got hit I would have bowled half the overs I did. Opportunity presented and I cashed in. In our minds we were still in the game and we got Greenidge. We got Greenidge and thought we had a chance.”

Australia lost the game, but Hughes had grabbed his chance. His 13/217 in the match remains the best figures claimed by an Australian in a losing cause. A cult hero had been born. “I confess to being a Hughes convert,” Peter Roebuck wrote in the SMH. “He may be a cricketer of spit and sawdust but his spirit is infectious.”

Battered and bruised all summer, Australia were desperate for anything, anyone to cling onto, and Hughes was the ideal candidate for a side in the dirt. His iconic moustache, penchant for a swear-filled sledge, and love of food and drink made him the archetypal Australian, but his appeal went beyond pure aesthetic.

Hughes was popular for more than just his handlebar mustache

Hughes was popular for more than just his handlebar mustache

As Martin Blake wrote in The Age: “Another lad, is Merv. Like the outer’s representative on the national team.” The everyday fan could relate to him, how he put his utmost effort into every ball, how he walked like a tearaway even if ‘fast-medium’ was a more apt descriptor. He claimed wickets through sheer force of will. A nation was hooked.

An appearance at the MCG, his home ground, saw his popularity reach its apex. In the 80s and 90s it was a teenage rite of passage to skip school and go mad at a one-day game, and Bay 13 was the national epicentre of the movement.

Australia had snuck a few ODI wins on the bounce and the 73,000 spectators thought it nothing less than a heavyweight title bout, with Hughes their prize fighter. The stands were a sightscreen of daubed bedsheets that day – ‘Merv FOR PM’, ‘That’s Mervellous’, ‘Merv Magic’, ‘Mervmania’. The MCG was Hughes’ own shrine, and the adulation soon crossed into imitation. Hughes picks up the tale.

“I’m on the boundary in front of Bay 13 and AB gives me the wave to warm up to bowl. I did a few exercises and heard a bit of a roar but every time I turned around there was nothing happening.

“At the end of the over Deano [Dean Jones] came up and asked me what was going on, and I just said I think they’ve had too much to drink. He said, ‘It’s looking good from here, there’s 20,000 people copying every exercise, what are you going to do next?’ I thought, ‘Well I might invent a few more exercises.’ So that’s when I started mucking around with the crowd.

“AB was in on it too! He said, ‘That’s great, we need the crowd support, but if you drop a catch or misfield it stops.’ I was at fine leg as the innings started that night and Dean Jones at third man in front of Bay 13. Before Terry Alderman came in to bowl, he could hear Bay 13 chanting ‘We want Merv’, so he held things up just before Terry ran in and said, ‘Right, Merv and Deano, swap’ so now I was at third man to do the exercise routine!

“Over the years I’ve ran into 100,000 people who claim to have sat in Bay 13 that night. Shit, I can’t remember Bay 13 being that big!”

The story of that summer, of Hughes and that Australian team’s mass appeal, remains relevant today. The series against West Indies was surrendered 3-1, and Hughes took just one more wicket after his 13-for at Perth.

“There was still a gulf between my best and worst that made me edgy,” he says. “In between people chanting ‘Merv, Merv’ some bloke on the hill yelled out at me: ‘Hey Hughes, you’re not that fucking good, how many wickets have you taken since Perth?’ I put up the two fingers as if to say ‘fuck you’, and he replied ‘And you can’t count either’ – the best sledge I ever copped!’”

Even as true success eluded him, Hughes remained able to laugh at himself. In 2018 as the Australian team and its public try to reconcile, the ‘winning cures all ills’ answer doesn’t add up to the fervour that developed 30 years ago around a team that had won one series at home in four years, and a player who still averaged 37 with the ball in Tests. They proved that it’s possible to be adored without the adulation being dependent on success.

***

Still, with England their next opponents, Hughes knew the goodwill would run out at some point. “The side was being picked for England and I was still one of the fringe players, I wasn’t assured of a spot. You’re not going to get picked because you’re a character or a good bloke.”

Hughes celebrates reclaiming the Ashes

Hughes celebrates reclaiming the Ashes

Hughes was selected to play in the Ashes and was accused of exactly that. “Off the back of the exercise stuff, when we went to England the media was all about me,” he says. “AB liked that because it took the pressure off the rest of the team and it wasn’t going to worry me.

“There were jibes going around that I’d only been picked because I was a character but I thought once it got started they’d write about who was getting runs and wickets and it wouldn’t be me, so I went along for the ride, it was all good fun.

“They called me a surfie from Bondi – I’m not from New South Wales and I’d never been on a surfboard in my life! I learned a lot about myself from the tabloids.”

Billboards depicted him with beer froth in his moustache, but 19 wickets in a 4-0 series smashing ensured Hughes and Australia had the last laugh. They wouldn’t relinquish the Ashes for another 16 years.

And yet, while Hughes played 42 of Australia’s 47 Tests after the 88/89 season, claiming 177 wickets at under 27 in them, and while Australia reached No.2 in the world with Hughes in the team, and No.1 the year after he retired as the West Indies were finally toppled, his legacy rests not on the years of success, but on the summer he came to be loved.

“It’s helped me since, don’t worry about that, I’m still living off that season. People still walk up and all they want to do is the stretching.”

Hughes gave Australia someone to cheer when they had little. Sometimes that’s enough.