First published in issue 26 of Wisden Cricket Monthly. Subscribe here

The West Indian workaholic explains how he became one of the most prolific and durable fast bowlers the game has seen.

First published in issue 26 of Wisden Cricket Monthly

From the get-go I wanted to play cricket. I had a special love for the game from an early age and just wanted to play all the time. I started out playing for Melbourne Cricket Club in Jamaica, the same club as Mikey Holding, and then watching West Indies play for the first time gave me those vibes that this was something I wanted to be involved with.

When I made my Test debut in Australia in 1984, alongside Mikey, Malcolm Marshall and Joel Garner, there was a wow factor to be in the same team as these superstars. But it wasn’t intimidating. This was a boyhood dream come true.

I was very dedicated to looking after myself from an early age. I probably wasn’t as talented as some of the guys I played with when I was a youngster so I saw fitness as a way of getting up to their level. I was always prepared to do more than my teammates. I tried to get as fit as I could to manage whatever workload came my way. I did a lot of running in the early days to make sure I was in good health and that whenever I was asked to bowl, I was ready to bowl.

Walsh celebrates West Indies’ victory over Australia at the Adelaide Oval, January 28, 1993

Walsh celebrates West Indies’ victory over Australia at the Adelaide Oval, January 28, 1993

When I was a young kid at Melbourne they used to laugh at me when I was running in the evening. After practice everyone would go indoors to play table tennis and I would be outside running, doing an extra couple of laps. I would always do extra, mornings and evenings. I got my body accustomed to bowling long spells and that was probably one of the reasons why I didn’t break down as often as some other fast bowlers. I always pushed myself.

I didn’t get much coaching when I was a youngster and my action got better with experience – playing games and watching videos, gradually fine-tuning it. I was never really coached about the rudiments of fast bowling. I remember the first time I probably got coaching was when Andy Roberts came to Jamaica to do a fast-bowling clinic but I was already playing for the national team by then so it was more a case of giving me advice and things to think about. Before that I was doing everything raw.

I had a natural inswinger as a youngster and with experience and exposure I became able to swing the ball both ways and seam it both ways off the wicket. And the fact that I was tall meant I got more bounce than most people.

I got a lot wiser as my career went on. I understood my game more and what I needed to do to get the best out of myself. I probably didn’t get to that point until I was about 27, 28. As a youngster you want to run in and try and bowl as quick as you can but later I got smarter and stayed more focused on what was required.

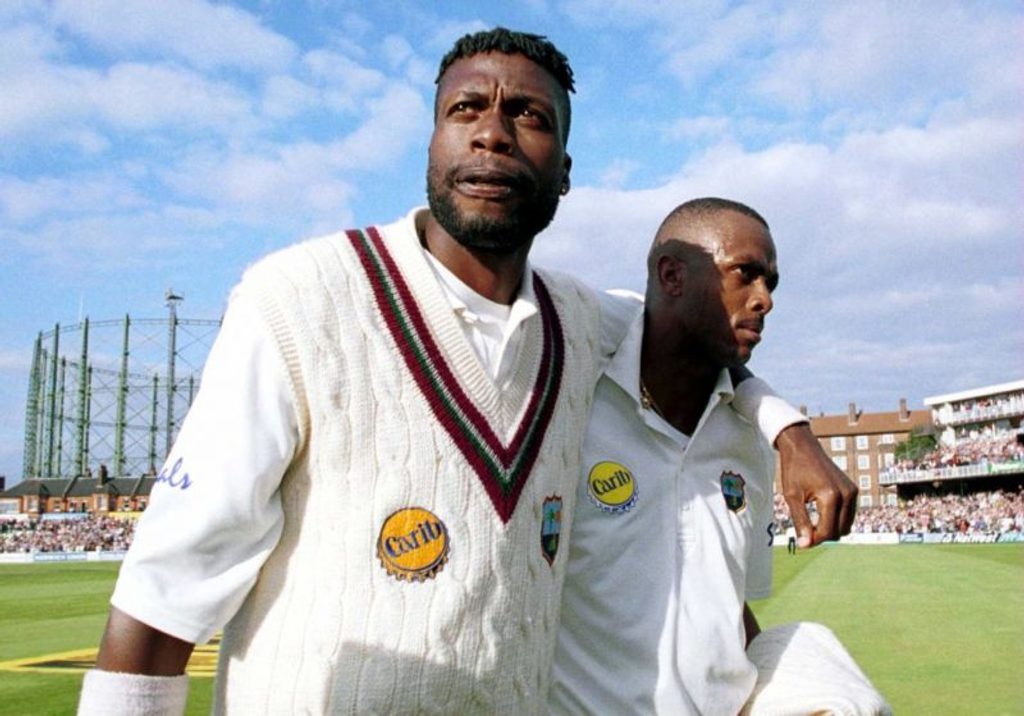

Walsh & Ambrose – one of the great bowling partnerships

Walsh & Ambrose – one of the great bowling partnerships

At the start of my Test career I would be first or second change but when you’re the leader of the pack you need to do things differently. It’s your job to dismiss those opening batsmen, to get the ball rolling. Whereas coming on later, it might be more about containing.

Curtly [Ambrose] and I complemented each other and we didn’t compete against each other. If it was Curtly’s day I would enjoy his success and if it was my day then he would do the same. In tandem we had a good understanding. We would try and build pressure, give nothing away. We looked out for each other. If he saw something wrong he would tell me, and I knew I could do the same.

It was very, very special when I passed Kapil Dev to become the leading Test wicket-taker and even more special that I did it at my home ground in Jamaica. Those are memories you can never forget, they will always be there. And then to top it off ‘Paddles’ [Richard Hadlee, who had held the record before Kapil Dev] spoke to me on the phone and wished me well. He was always a friend of mine, we had that mutual respect, so to receive a call from him was a pleasant surprise as well.

Jason Gillespie picks out the high points and hurdles from his technical journey. In association with @proatar.https://t.co/VNiP3JaFqC

— Wisden (@WisdenCricket) October 27, 2019

The ability to vary my pace was something I learned the more I played. It’s not something that happens overnight, you have to work hard. I tried different grips and tried not to change my action because then the batsman knows what you’re doing. Those variations were particularly effective on certain wickets. Not all pitches were bouncy and fast and I needed to make sure I had another way of outfoxing the batsman.

The Graham Thorpe slower ball [at Old Trafford in 2000, trapping Thorpe lbw for a golden duck] was something I’d worked hard on and I was happy when my plan worked perfectly. Not every time you plan something will it work to perfection. I had discussions with myself about how best to get him out because he was a high-class player. I didn’t really discuss it with my other teammates. Sometimes you discuss things and word might get out. So that one I kept to myself and it was only after the execution that I spoke to Curtly about it.

Batting was something I enjoyed but I wasn’t able to get as much bat on ball as I would’ve liked [Walsh holds the record for the most ducks in Test cricket with 43]. I didn’t get as many runs as I wanted but I always tried to do the best I could.

Courtney Walsh is one of the legends of cricket available on Proatar, the coaching and mentoring app. Send a video of your skills and get it analysed by Courtney. Download the app at proatar.com/download and use code PRT10WIS to get 10% off your first booking.