The Yorkshire–Lancashire rivalry is the ancient trans-Pennines feud that stretches across the backbone of England and which looks set to endure well into this century and beyond. Richard H Thomas examines English cricket’s thorniest neighbourly scrap.

First published in 2015

Three cheers for “Lancashire hotpot”, “crumbly cheese” and “Eccles cakes” wrote Jeanette Winterson in Country Life. In response, Nigel Farndale acerbically suggests that “the problem with Lancashire, if you face the thing squarely” is that “it’s not Yorkshire”. So it has been since they first formally squared up to each other with bows, arrows and vats of boiling oil; though represented by the sweetest smelling blooms, arguments about who is there to keep the wind off whom have barely desisted.

Cricket-wise, official Roses hostilities began in 1867 with a Yorkshire victory at Whalley, near Blackburn. Yorkshire all-rounder Roy Kilner defined the ideal ‘Roses Match’ as having “no umpires and fair cheating all round”. Even in their most modern manifestation, passions still run high: in 2014, Yorkshire’s Andrew Gale got into hot water for calling Lancashire’s Ashwell Prince “Kolpak”. References to anyone being a gun-for-hire are especially acute in a fixture that’s all about belonging. Summarising 150 years of testiness, ex-Yorkshire skipper Martyn Moxon reflected in 2011 that “…there have been issues, but it’s not as if we go into these games thinking, ‘Let’s do this lot’. It’s more of an unfortunate case of stuff happening.”

Not that Roses clashes were always so exciting. Early tussles acquired a reputation for dourness; allegedly an unwritten law suggests “no fours before lunch”, as if that would be adding too much frivolity to an otherwise solemn ritual. Michael Parkinson reports that among his father’s sage cricketing advice (nothing flash, never cut until July, remember it’s a side-on game) was that “only a girl who can sit through a Roses match without yawning” should be considered a suitable wife. So forbidding could the cricket be, that Geoffrey Moorhouse recalls a Roses match when Winston Place and Phil King took four hours over their centuries for Lancashire, and everyone considered it to be “pretty palpitating stuff”.

Traditionally Roses cricket is no place for the faint-hearted neutral. The great writer Neville Cardus recalled that when an impartial onlooker suggested that the action was rather prosaic, he was told from all directions: “It’s nowt to do with thee”. Another time, a non-connected spectator returned to find his seat occupied by a ruddy-faced northerner. “Excuse me,” he protested, “but I left my hat on my seat” only to be told that in these parts, “it’s bums what keeps seats, not ‘ats”. When the Roses lock thorns, spectators are driven to deep and thoughtful introspection; Moorhouse says it reminded him “who I am and what I am about” – a man “with a responsibility to discharge so that a legend shall live on into the recollection of his children”.

Furthermore, he suggests: “It is the only event which I allow to justify the wearing of a tie”, it being “unthinkable”, especially in the “enemy camp” that he should not appear “without that dark blue silk sprinkled with the neat red roses of my county”. Cardus recalled a Yorkshire clergyman admonishing the England selectors for damaging the wider interests of the game by picking Lancashire and Yorkshire players for representative cricket, drawing them away from their “main and primary duties”.

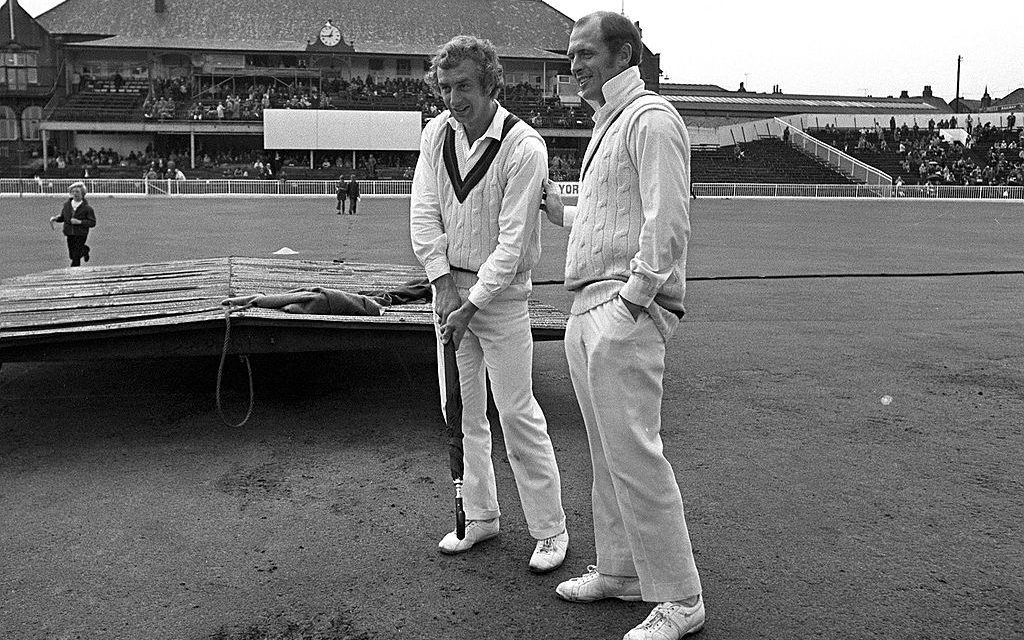

Bumble and Boycs: northerners in excelsis

Bumble and Boycs: northerners in excelsis

For Yorkshire, suggested JM Kilburn, “cricket has always been a private enterprise with a public responsibility”, but an equal case can be put for Lancashire. In both counties, hard cricketers are weaned on hard cricket in the leagues. Indeed, only when one considers the respective rolls of honour does Yorkshire establish some bragging rights. Having won the County Championship title 31 times outright in all, between the early 1890s and WWII, their grip on the silver trophy never relaxed for long. Lancashire have triumphed many times less, but that’s not the full story.

The Red Rose county holds the historical sway when it comes to the shorter formats. Back in the Seventies, with overseas talent like Clive Lloyd and Farokh Engineer beautifully complementing local lads like David Hughes, Harry Pilling, “Flat Jack” Simmons and David Lloyd, Lancashire realised sooner than everyone else how to win one-day cricket matches. While Lord’s became a regular September day out for them, Yorkshire cricket began killing itself slowly with a thousand bitter cuts, administered, suggests Rob Bagchi, by “pro and anti-Boycott factions” which “left the club thoroughly demoralised, impoverished and moribund both on and off the field”.

Up until 1991, you still had to be Yorkshire-born to play for them, Michael Parkinson noting that concerned fathers-to-be would fly their pregnant wives back home. “You felt an affinity with the club,” reflected Geoffrey Boycott, “heritage” and “upbringing” providing the spur to compete. In 1992 though, the introspection ended, as Bagchi reports: “The club’s cricket committee finally dismantled the Broad Acres-born policy that had, with a few breaches that were brushed under the carpet, prevailed for more than 70 years”.

Northern Byas: Yorkshire legend David Byas crossed the Pennines in 2002 – the first man to do it in living memory

Northern Byas: Yorkshire legend David Byas crossed the Pennines in 2002 – the first man to do it in living memory

The first overseas signing was Craig McDermott, but he pulled up lame before arriving and a rethink was needed. Soon a young fellow called Tendulkar was posing in a flat cap with a pint of the county’s finest, making him, Bagchi suggests, “the most incongruous Tetley Bitterman to date”. New members joined in large numbers and there have been few reasons since to doubt the wisdom of the more inclusive policy.

For 2015, Yorkshire have captured two of the hottest one-day signatures around – Aussies, Aaron Finch and Glenn Maxwell. While the playing field is more level these days, defections across the Pennines are rare; Julian Guyer reports that when David Byas joined Lancashire in 2002, it was “the first instance in living memory of a captain of one team joining the other side”. Dickie Bird pronounced himself “stunned”, though perhaps not as much as Byas when in his first innings for his new county he was despatched lbw first ball by Barrie Leadbeater – a Yorkshireman.

Byas reflects that these days the rivalry lacks some of the old-time ferocity, and while the “pride, history and tradition” remain, “it doesn’t have quite the same bite” as it did. Martyn Moxon also feels that generally “both teams get on well”, and no harsh words between Gale and Prince seem likely to change that. The increasingly hybrid nature of cricket means that the bitterest of old scores remain in the past; perhaps it hasn’t been the same since the war, suggested Fred Trueman; after “long years serving alongside one another” the full passion of the rivalry was “difficult to recreate”.

Peace has really broken out when, as Tom Collomosse points out, an Old Trafford crowd can “dispense with parochialism” and boo David Warner “with every last breath” for having the temerity to challenge Joe Root – a Yorkshireman – to some late night fisticuffs. Indeed, Bolton-born Geoffrey Moorhourse admitted to always finding it hard to whip up “the proper degree of belligerence” towards the Yorkshire team or its crowd; Mancunian Cardus wrote that “the Yorkshireman’s intolerance of an enemy’s prowess” is simply the measure of “his pride in his county’s genius for cricket”.

If Imran versus Javed and Botham versus Chappell are toxic, in comparison Yorkshire and Lancashire are two curmudgeonly old men who shake their sticks at each other then nurse half a bitter apiece while they fix the world’s problems. Long may they continue to do it; with national fortunes in flux, we need the two great houses of Lancaster and York to lead the recovery.