In 1981, the Lancashire League was a hothouse of overseas talents and personal rivalries, with little respect given to big reputations until Michael Holding, the most feared bowler in the world, stepped forward as an overseas pro for Rishton CC. Stand well back …

The Pinch Hitter aims to help out freelance cricket writers during the current coronavirus crisis. Read on a pay-what-you-can basis here

First published in Issue 6 of the Pinch Hitter

The Kensington Oval in Barbados is a raucous ground at any time, but on March 14, 1981, when Clive Lloyd told Michael Holding for the first time that he and not Andy Roberts would have choice of ends, it was frothing. In deference to his mentor, Holding replied, “Whichever end Andy doesn’t want” and duly took the second over. And what an over it was. The unfortunate batsman taking strike was Geoffrey Boycott, master technician but recently turned 40. After being speed-roasted for five balls – Holding at his rhythmical best, running in purposefully but smoothly, head still and slightly forward, a cheetah prepared to pursue his quarry over miles of savannah – the sixth sent Boycott’s off-stump into a series of Simone Biles floor-routine cartwheels, an iconically brutal moment from the snuff-movie show-reel of one of cricket’s most unforgiving teams.

Thirty-six days (and two Test matches) later, in a village four miles west of Blackburn, Ramsbottom CC’s opening batsman, Peter Ashworth, might well have had those images flashing through his mind as the lean and mean 27-year-old Jamaican stood at the top of his run and prepared to send down his first ball for Rishton, defending just 108. Ashworth survived physically intact, but didn’t make many as ‘Rammy’, despite wobbling from 93-4 to 94-7, managed to scramble over the line. Suffice to say, the surface lacked some of the zip of Bridgetown.

If the pace-pacifying club pitches of a Lancashire April provided something of a culture shock for Holding, then the abandonment of the following Saturday’s game at Colne due to snow was stark proof that the cricket was going to be decidedly un-Caribbean. Not that the snowfall accounted for the full fixture list that day. Indeed, Holding’s West Indies new-ball partner Roberts, arriving a week later than his colleague to pro for Haslingden, woke up to snow-dusted Moorlands but was told their game at East Lancs was still on. “I don’t think he’d ever seen snow before,” recalls Haslingden skipper Bryan Knowles. Holding had seen snow, but never before walked in it.

Together with Rishton’s club chairman, Wilf Woodhouse – owner of a shop on Rishton High Street that rented TVs and top-loading video recorders – Holding headed over to Blackburn to watch Roberts bowl in several sweaters, the snow having been swept off the outfield and piled around the boundary. Later, he visited his mate in the dressing room, where the pair huddled around a one-bar gas heater. Not so much Whispering as Shivering Death.

Woodhouse had approached Holding during the previous summer’s Old Trafford Test and impressed the Jamaican with his bullishness, as Holding would later record in his autobiography, No Holding Back. “Wilf was very enthusiastic; I liked that. He told me that the standard of cricket was good and I would not find it a chore. He said that Rishton would pay me £5,000 for the summer. In those days that was a lot of money, especially for playing at weekends only. After discussing it further, I thought, why not?” He left his job in the Central Data Processing Unit of the Jamaican government and took his “first venture into professional cricket outside West Indies”.

Woodhouse would also loan Holding to Lancashire for seven first-class and seven List-A matches that summer – reputedly claiming back some of the outlay, although the county commitments had to fit around Rishton’s needs – but if anyone thought that having the world’s quickest bowler in their ranks would simply blow other sides away, they was sorely mistaken. Not least because the league was littered with international pros, including five players who would take part in the World Cup final a couple of years later: Holding, Roberts and three Indians.

Rishton recorded a first win the following week, over eventual champions Rawtenstall, for whom Franklyn Stephenson would take 115 wickets at 9.65, top in both categories and all faithfully recorded by future TMS scorer Malcolm Ashton. But things got weirder still for Mikey a week later when Church CC skipper Ian Osborne, an IT manager, plonked him for four sixes, not something to which he was all that accustomed. Especially not by an Englishman.

“It was a very wet day,” recalls Osborne, “and there was a reasonably short leg-side boundary. Michael would say that he wasn’t bowling at full pace, but he was still pretty quick. He was at the height of his powers at the time. He wasn’t coming over as a has-been. He was The Man. Anyway, the first six I top-edged and it hit the sight-screen behind me. Clearly, he wasn’t slow. There were two over square leg, front foot pulls, and the other was a pick-up over mid-wicket.”

Osborne’s exploits even saw him make the national press, with a report in The Daily Star: “It was the original 15 minutes of fame, the sort of thing that is never going to happen in your life. It was quite, quite strange.” Even more so considering that Holding, playing for Lancashire against Somerset the following week, dismissed Vivian Richards in both innings. Four weeks later, Osborne added an unbeaten 33 in a match that succumbed to bad light, averaging 99 for the two games.

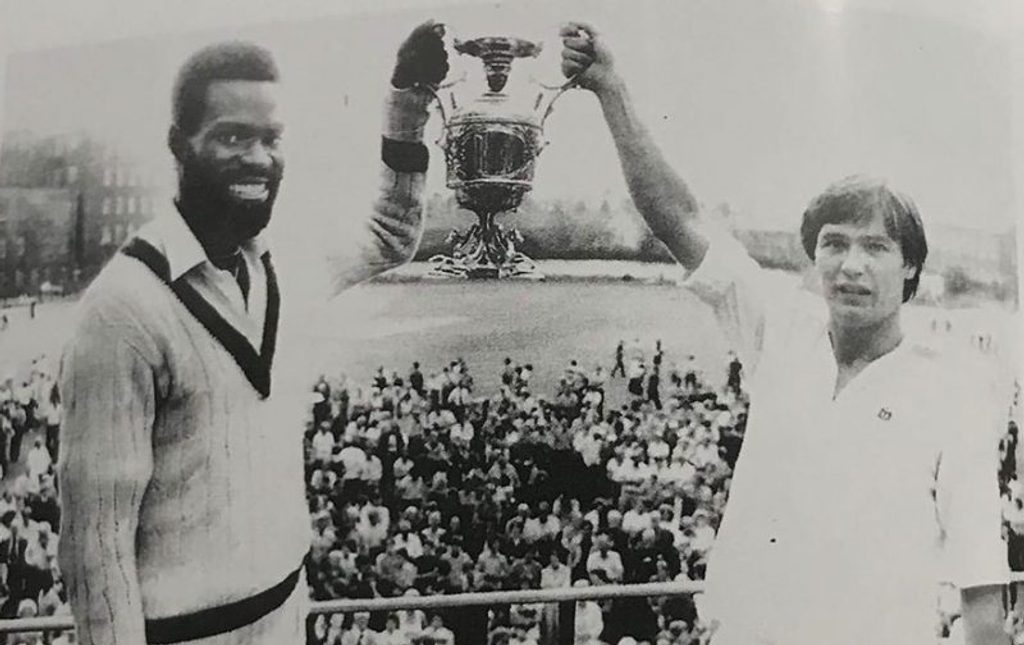

Franklyn Stephenson left (pipped) Holding in the wickets tally

Franklyn Stephenson left (pipped) Holding in the wickets tally

Besides such idiosyncratic fixture lists that threw up home and away fixtures within a few weeks of each other, another quirk of the Lancashire League were its eight-ball overs, 34 per innings. And Mikey was expected to bowl half of those, which meant he rarely bowled off a full run, recalls wicketkeeper Frank Martindale: “Michael said, ‘I won’t bowl at top pace against the amateurs. These guys have to go to work on Monday morning to earn money to feed their wives and kids. I wouldn’t feel right hurting them’. A couple of times he really let it go against the professionals. And some of the amateurs said he bowled quick at them, and he might have done, but not as quick as it could have been…”

After his first encounter with Church, Holding took back-to-back 5-36 hauls – the first in a narrow defeat to Madan Lal’s Enfield, the second to back up 47 not out in a win over Colne – followed by 7-51 at Ramsbottom. Rishton were starting to find their feet, even as the Jamaican was struggling to keep his, on wicket ends that, away at least, were invariably wet, regardless of the weather. “I remember turning up for an away game once,” he wrote in No Holding Back, “and for the entire week before the weekend it had been nice and sunny. I thought, finally I’d get a dry pitch, but when I got there the square was soaking wet. Now Lancashire is not such a wet county that the rain comes from under your feet, so I think someone must have said, ‘Hey, that Holding’s here on Saturday – get the sprinklers out.’”

But as June rolled around, the water did plummet from overhead and three of Rishton’s next four games failed to produce a result. The one that did reach a conclusion was the return against Rawtenstall, although only after a delayed start that saw Holding accost Franklyn Stephenson to ask where the nearest bookies was. The Barbadian found out, he writes in My Song Shall Be Cricket, and accompanied Holding on what was Stephenson’s first experience of a betting shop. “After a short while inside, which felt like ages, I asked if we shouldn’t check on the conditions of play. Michael’s response was to assure me that no play would be possible with all the rain that had fallen. I left and went back to the ground to find our ground staff and team in full flow getting water off the ground.”

Soon, the umpires had decided upon a start time, meaning Stephenson had to “go back to the bookies and call Michael”. The game was trimmed to 20 eight-ball overs, and Holding’s figures were 10-0-98-3, with his betting chaperone slamming 81, “a mauling that he did not forget as he showed me when we met again in Tasmania a few months later”.

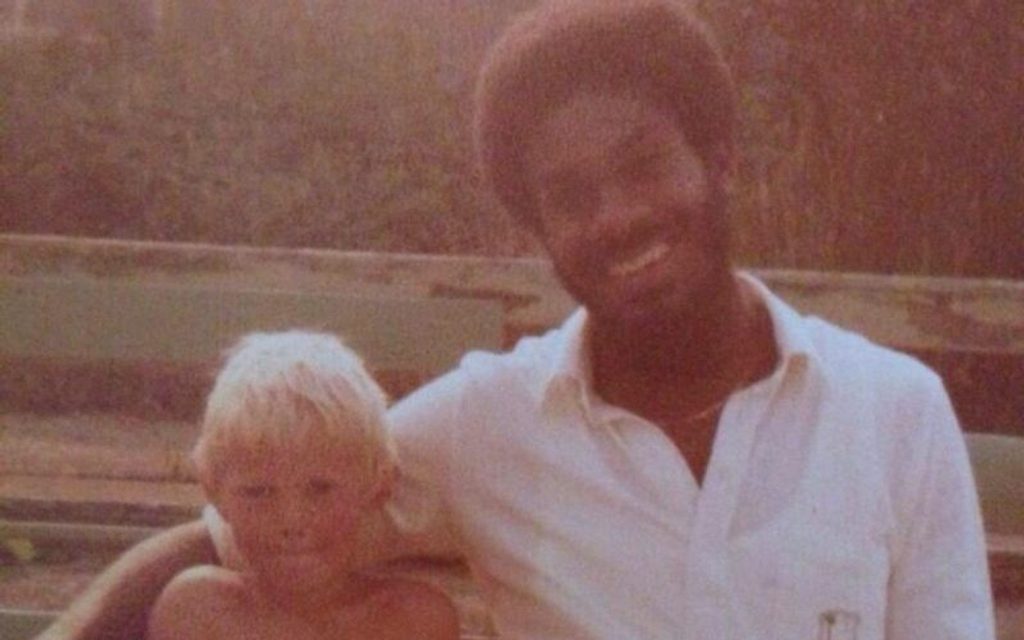

Holding, pictured with fan Ben Law, was a huge hit in the shires

Holding, pictured with fan Ben Law, was a huge hit in the shires

After a pair of County Championship outings against Surrey – Holding having been chauffeured to both games by Accrington-based offie ‘Flat’ Jack Simmons, who always stopped off for a mushy pea-based supper on the way home – late June brought back-to-back games against Lowerhouse. This meant Mohinder Armanath, who would of course win Player of the Match in that Lord’s World Cup final two years hence.

Rishton lost the first, away, by five runs, Pankaj Tripathi’s 47 out of 134 proving decisive. Unfortunately, it went to his head and in the lead-up to the game at Rishton there was some bravado-fuelled trash-talk that backfired spectacularly. Lowerhouse were routed for 67 – Armanath 43 not out – with Tripathi hit in the face by the West Indian and having his nose broken, temporarily interrupting a short innings in two acts. Holding’s figures did his talking for him: 13.3-6-13-9, with seven bowled and two caught behind. ‘Holding and Hill rout ‘House’, declaimed the local paper, perhaps overstating Barry Hill’s role in it all.

Poking the bear was evidently a fairly average idea, but it wasn’t the only bee in the Holding bonnet. He had regularly used his weekly column in the Lancashire Evening Telegraph to bemoan the reluctance of local players to walk. Lowerhouse’s Stan Heaton recalls an incident during the first of the head-to-heads. “In the game at our place he hit me on the chin and first slip caught it. Obviously, I didn’t walk, because I hadn’t hit it. He started to have a pop at me, but then stopped when he could see the blood trickling down my chin.” In the absence of hot-spot, bloodspots will have to do, although some club batsmen may well have been tempted to walk anyway.

There was further non-walking shenanigans in the next game, at East Lancs, when Holding sent down 8-4-9-0 before limping out of the attack with back and ankle niggles. The non-departing batsman was Brian Ratcliffe, who would go on to make an unbeaten 101 out of 170 all out after getting away with gloving a Holding bouncer to leg gully.

Holding: “I enjoyed my time with Rishton, although not the cricket”

Holding: “I enjoyed my time with Rishton, although not the cricket”

“He immediately started rubbing his head,” recalls Martindale, “and the umpire fell for it. Michael turned and asked: ‘Why isn’t that out?’ He said it had hit him on the head. Michael said: ‘Umpire, if that had hit him on the head, he would be dead’. Brian admitted it in the bar later. And that winter, after we had re-signed Michael for the following season – although he didn’t come back because of knee surgery – Brian actually joined Rishton. He left East Lancs so he wouldn’t have to face Michael Holding again!”

A simmering Holding took his third 5-36 haul the following week – another defeat, though, Rishton’s seventh in 11 completed games – but the ankle problem saw him play just two matches in 42 days through the rump of July and August. Both were against Nelson, whose pro was one Kapil Dev.

In the first match, at Rishton, Kapil made a third of his team’s total. Unfortunately, that was only 18 as Nelson subsided from 54-4 to 54 all out, Holding taking 7-16 in a 10-wicket win (although not the Indian all-rounder, who fell to the left-arm swingers of Blackburn Rovers centre back John Waddington). In the return, Nelson were 45-9 when the rains saved them, giving them an aggregate of 99-19.

“‘Here are my weapons’ he seems to say. He looks so relaxed, so in control.”@benjonescricket on the iconic Holding photo from 1976, an image that perfectly captures the man’s charm. https://t.co/ItwsIomVKQ

— Wisden (@WisdenCricket) April 29, 2020

With six games remaining, Rishton were nailed on for mid-table mediocrity, leaving little for Holding to play for save professional pride – not least in consecutive Sunday head-to-heads with AME Roberts’ high-flying Haslingden that followed a pair of Saturday wins over Accrington and Bacup.

The first, at Haslingden, saw the home team amass 205, Holding taking 5-68, with Bryan Knowles making 96 of those after getting away with a feather through to the keeper off Holding in the first over and later having the audacity to pop the Jamaican back over his head for a one-bounce four. Roberts then took 4-29, including Holding lbw for a single, as Rishton crashed to a 104-run defeat.

Having warmed up for the return match with 4-17 on the Saturday, Holding was ready to settle accounts with his Antiguan amigo, although perhaps even he didn’t imagine it would come with the bat. Stuck in on a tricky pitch, Holding slammed 75 out of 132 all out, with the next highest contribution being just 13.

In reply, only one visiting batsman made it to double figures – Knowles again, with 70, en route to becoming the first amateur since 1929 to make a thousand Lancashire League runs, the first to top the overall averages for 24 years, astonishing given the quality of pros. Haslingden were tumbled out for 117, Barry Hill taking a career-best 8-27.

The penultimate weekend brought defeat at Accrington – Holding playing on the rest day of the Roses match, in which he bagged match figures of 10-115 at Headingley – before the Jamaican signed off with a demob-happy 52 against Bacup, peppering Rishton’s short straight boundaries off the left-arm spin of a teenage Keith Roscoe.

“I remember it well,” says Roscoe, who runs a racing pigeon accessories company and is still going strong 39 years later, second on the league’s all-time wickets chart. “He hit the first four balls of the over for 24 – four consecutive sixes – and I had him stumped on the fifth. Now that’s what you’d call buying a wicket. One of our lads got injured crashing into the sight-screen trying to catch the fourth of them. It had everything, that over: runs, wicket and an injury. It’s a good job I got him when I did, though, what with ‘em being eight-ball overs…”

Holding finished the campaign with 86 wickets at 10.74, second to Stephenson on both counts, and 418 runs at 26.12 as Rishton finished sixth of 14. He was, by all accounts, the same polite, amiable and dignified man that has provided mellifluous musings in the Sky commentary box these last couple of decades, the same principled yet occasionally cantankerous soul who disdains Twenty20 and comes off the long run about other well-known bugbears. One of them being the Lancashire weather.

“I enjoyed my time with Rishton, although not the cricket,” he wrote in the autobiography. “It was not as high a standard as club cricket in Jamaica and – the Lancashire tourist board will be gunning for me after saying this – it was forever raining.”

Having seen that over to Boycott, one or two local batters might have welcomed pulling back the curtains to see it persisting down.