While many counties greeted the advent of limited-overs cricket with suspicion or distaste, Jack Bond’s Lancashire embraced the new format and brought the good times back to Old Trafford, winning five trophies in the space of four seasons, writes Paul Edwards.

First published in July 2017

First published in 2017

If limited-overs cricket ever stops reinventing itself in glitzier, more customer-friendly formats, there must be a chance that some courageous soul will write a history of it. The author may pay attention to the development of short-form, evening cricket in England before the counties became involved and he or she will certainly note the landmark year of 1963 when a 65-over knockout competition was introduced.

However, in order to identify the ancestor of the riotous enthusiasm that characterises the IPL, the Big Bash or many matches in the Blast, our historian will probably have to delve into Lancashire’s history in the late 60s and early 70s, when people took to one-day cricket with an enthusiasm that was unmatched anywhere else in England, with the curious exception of Kent. It was an era when crowds filled Old Trafford for 40-over matches on Sunday afternoons and regarded their trips to Lord’s for knockout finals as annual holidays, or ‘wakes weekends’, if you will.

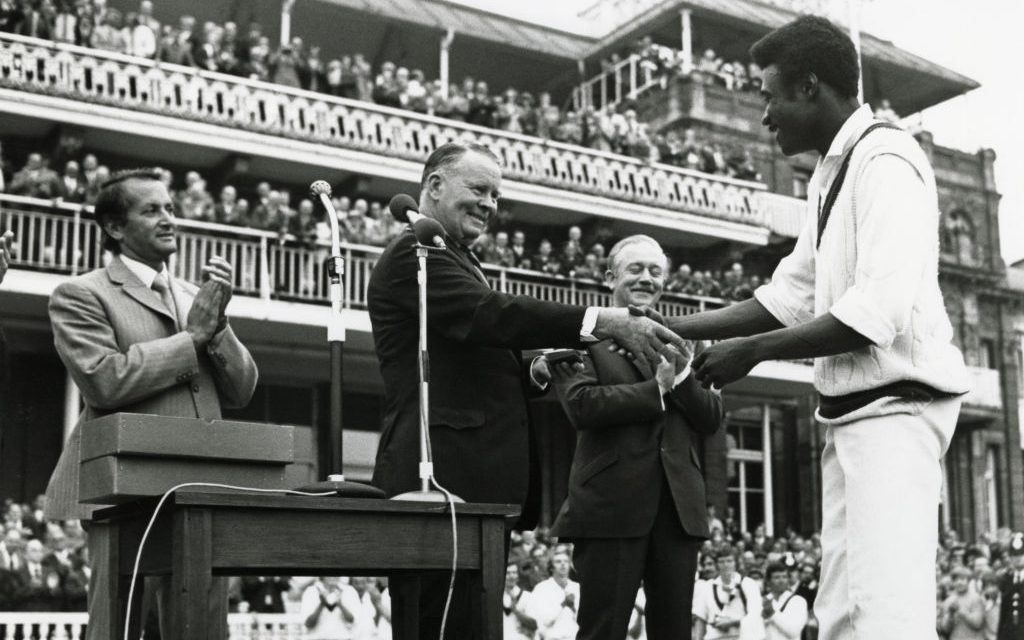

Jack Bond is presented with the Gillette Cup trophy by MCC president and former England cricketer Freddie Brown at Lord’s in September 1972

Jack Bond is presented with the Gillette Cup trophy by MCC president and former England cricketer Freddie Brown at Lord’s in September 1972

Stories are still told at Southport of the multitude that filled Trafalgar Road on July 13, 1969 to watch Lancashire’s keeper-batsman Farokh Engineer smack 78 not out in a nine-wicket victory over Glamorgan. Wisden put the attendance at 10,000 but no one is really sure. What is certain is that the gates were locked half an hour after the start of the game and that any comparable attendance on this club ground today would send the Health and Safety Gauleiters into masochistic apoplexy. All this for a format which many wise observers dismissed as not cricket at all.

What had happened? And why had it happened in Lancashire?

The first question is the easier to answer. In the late 1960s county cricket was short of money. The one-day knockout competition, eventually called the Gillette Cup, offered a maximum of four home games each season and so a sponsored 40-over Sunday league was introduced in which each bowler could deliver no more than eight overs and was limited to a 15-yard run-up. Games began at 2pm and one was shown live each week on BBC2. They fitted neatly into leisure patterns.

Lancashire won the first two John Player Sunday League titles and in 1970 secured the first of a memorable hat-trick of Gillette Cups.

The irony was that the captain who inspired them to win five trophies in four years – their first silverware since they shared the Championship with Surrey in 1950 – was a devout Methodist and an outwardly conservative figure who made his Lancashire debut in 1955 and had only intermittently nailed down a first-team place. His name was Bond, Jack Bond.

Lancashire cricket was in a mess in the 1960s. Good players had been allowed to leave and the county regularly finished in the bottom half of the County Championship table. Bond’s appointment to replace the great and loyal Brian Statham, who retired in 1968, hardly had the air of a full-throated endorsement but it was typical of a committee which had allowed a mighty gulf to form between the players and officials.

“We’ve just had a committee meeting and they want you to take the captaincy on a caretaker basis while they look for somebody else,” the new skipper was told by the secretary, Jack Wood. Bond himself was delighted and David Lloyd, who had made his debut in 1968, cites the appointment as a rare example of the Old Trafford committee getting something right.

“The club had some wonderful players in the 60s but it was in the doldrums,” recalls Lloyd. “Initially in 1965 the committee stumbled on Brian Statham as captain, which was ridiculous because he should have had the job years before that. Jack Bond was an in-and-out first-team player but in their wisdom – and they didn’t have much of it – the committee then chose the right fella.

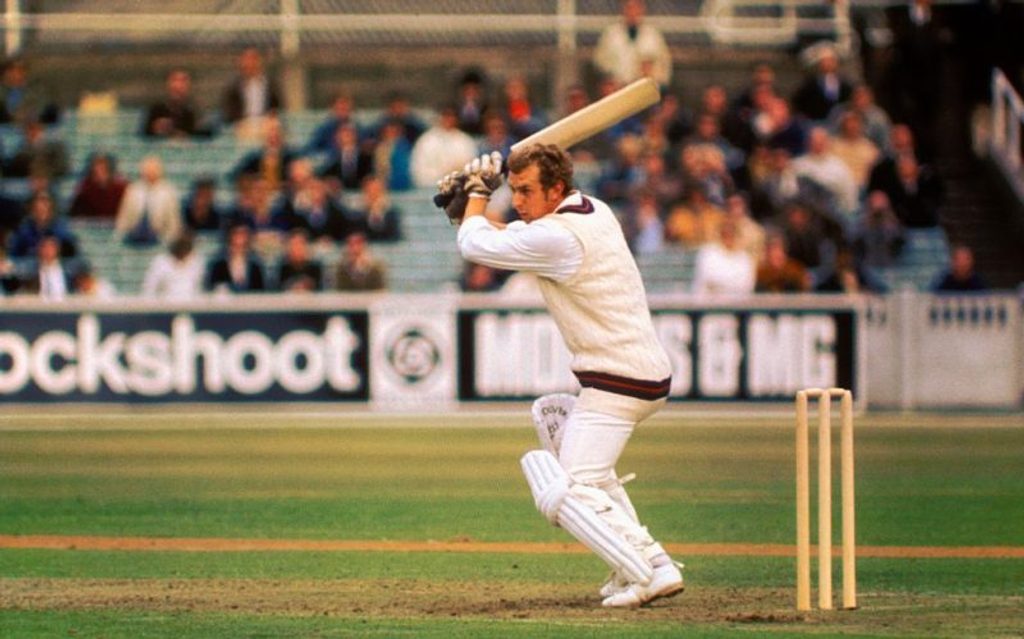

David Lloyd batting for Lancashire in the John Player League in June 1970

David Lloyd batting for Lancashire in the John Player League in June 1970

“Jack was a brilliant man-manager. He put everyone before himself. If we needed shoring up, he’d do it, if we needed someone to sacrifice themselves chasing quick runs, he’d do it. Jack understood that we’d all come from the leagues and were used to playing one-day cricket.”

Lancashire finished sixth in the 1968 County Championship, their highest placing in eight years, and even the committee could not fail to make the captain’s appointment official. What followed was four summers of glory as Lancashire engaged two overseas players, Engineer and Clive Lloyd, whose loyalty to the county became so deeply rooted that they still live there. When 40-over cricket was introduced in 1969, Bond embraced a format which other counties, Yorkshire amongst them, mocked.

“This new league can be the making of cricket,” he said in 1969. “We may not like sacrificing first-class principles in order to provide a spectacle but it is worth a try. Let us go out there and enjoy ourselves; if we do that the crowds must surely enjoy themselves, too.”

Make no mistake, the Championship was still by far the most coveted prize in the domestic game but the best position Lancashire managed was third, in 1971 and 1972. In the meantime the “one-day stuff” was certainly worth winning and the limited-overs formats were to be the making of Bond and many of his players.

David Lloyd celebrates with his teammates after Lancashire defeat Middlesex in the 1975 Gillette Cup final at Lord’s

David Lloyd celebrates with his teammates after Lancashire defeat Middlesex in the 1975 Gillette Cup final at Lord’s

Lancashire’s five trophies under Bond were deeply populist triumphs. The players felt a vastly greater affinity with the crowds who packed Old Trafford on Sunday afternoons than they did with the waistcoat-and-watch-chain officials in the pavilion. After all, most of the cricketers had come from the leagues in which many spectators still played. And although there were no Claphits or tedious pop songs, younger supporters gave their loyalty to Bond’s side and borrowed the theme song from the short-lived American show, The Banana Splits. “Lancasheer, la la-la laaa, Lancasheer, la la-la laaa” rang out over M16 as home batsmen set challenging totals and the meanest attack in the country choked the life out of opponents.

“We had an unbelievable never-say-die attitude and it was born of dissatisfaction,” says Lloyd. “Jack got us together and it was almost us against them, but the ‘them’ were the committee. We were such a tight unit and we all had the red rose on our blazer and, crikey, did that mean something. We used to go out at night in them.

“It was like Manchester United in that we felt the crowd gave us another player. Cricket in those days was very intimate, you could sit on the grass by the boundary but people behaved themselves. Then when the game was over, the spectators ran on to the ground and, you know, nobody died. It was fine, it was good fun. The crowd were showing their spirit and their will for you to win and when the game was done, we went into the bar with the crowd. But there were none of these flaming selfies, you just mingled with the people who’d watched you play.”

Lancashire’s tactics were essentially simple but they depended on skilled cricketers knowing their roles. The openers, Lloyd and Barry Wood, would aim to set a secure platform, a task in which they were helped by the diminutive Harry Pilling. Once that had been done, the stroke-makers and hitters would be unleashed, most notably Clive Lloyd, who used a 3lb bat yet managed to make it look like a twig. Lancashire also batted deep. Most of the bowlers could bat, with the spinners, Jack Simmons and David Hughes, being especially effective late-order hitters.

Indeed, it was Hughes who took 24 off a John Mortimore over in the famous 1971 Gillette Cup semi-final against Gloucestershire – a three-wicket victory for Lancashire which finished in near darkness.

It was an era in which games inspired folk-tales and cricketers became folk heroes, no one more so than Simmons, who first learned a trade as a draughtsman and then played as a professional for Blackpool before making his Lancashire debut aged 27. Many of those watching Simmons play for the county had faced his darts in league cricket – his nickname was Flat Jack – and they also knew of his appetite for fish and chips, preferably two large portions.

Clive Lloyd is presented with his Man of the Match award for his game-defining 126 in the final of the 1972 Gillette Cup against Middlesex

Clive Lloyd is presented with his Man of the Match award for his game-defining 126 in the final of the 1972 Gillette Cup against Middlesex

“Jack assembled a team of willing Lancastrians bolstered by Engineer and Lloyd,” says Lloyd. “You had Peter Lever and Ken Shuttleworth as your opening bowlers and you had Peter Lee in there on occasions. You had Jack Simmons and David Hughes, who were all-rounders really and massive hitters. You had John Sullivan and Ken Snellgrove, who could both hit a ball a long way. And then you had Barry Wood as your sixth bowler and Sullivan as your seventh.

“The attack was foolproof. I remember Mike Smith from Middlesex saying: ‘Well, we’ve come up for another good hiding.’ Our approach in the field was to squeeze the opposition and put them behind the rate. They had to do something if they were behind the rate and they weren’t going to do something against Simmons and Hughes.”

Yet when all the skills of that Lancashire team are described – not least the predatory fielding, with Clive Lloyd patrolling the covers like a haughty puma – one is left with a memory of an undemonstrative Boltonian in his late thirties directing operations with the air of a natural leader, one who had earned the unquestioning loyalty of his players.

It was the team that Jack built and his selections, however unusual, were accepted without demur. Not since the early 1930s had Lancashire cricket stood on such a pinnacle.