Amol Rajan, the BBC’s media editor and author of Twirlymen, the Unlikely History of Cricket’s Greatest Spin Bowlers, wondered what happened to the forgotten and formidable art of medium-pace spin.

This article originally appeared in The Nightwatchman, The Wisden Cricket Quarterly.

First published in 2017

First published in 2017

It is a curious fact that when cricket was first becoming popular in England, in the latter half of the 18th century, all bowlers were either spinners or had great ambitions to be. This was because at the time bowling referred to the action we now associate with ten-pin bowling: rolling the ball along the surface of the earth, from bended knee, as if making a proposal of marriage to the distant batsman. A bowler’s best hope during this, the dawn of the game, was for a mole-hill, fox-hole, or adder enclave to impart deviation and so befuddle the batsman. When, finally, bowlers were allowed to give the ball air – probably around 1770 – their under-arm actions couldn’t generate much pace. So they relied on spin.

All the reports, including those of John Nyren, author of cricket’s first notable work of literature The Young Cricketer’s Tutor, show that the earliest air bowlers, men such as Edward ‘Lumpy’ Stevens and Lamborn, the ‘Little Farmer’, used ‘twist’ to break the ball from off to leg or, more commonly, leg to off. The round-arm and over-arm revolutions were many decades away alas, so bowling was a twirlyman’s task. This pattern continued for so long that, rightly understood, the modern dominance of pace bowling is akin to a decades-long aberration from the norm. The history of mystery didn’t leave much space for pace.

On July 15, 1822, a maverick named John Willes, who had been pushing the boundaries of the laws of the game for over a decade, bowled a round-arm delivery for Kent against MCC at Lord’s. The umpires called no-ball. Willes threw the ball down in disgust, called for his horse and rode off into the sunset, scarcely playing again, so ostracised was he by cricket’s fraternity. Little did he know that he had planted the seeds of a revolution that would catapult the game into modernity. In 1828, MCC moderated Rule 10 to allow the hand as high as the elbow; in 1835 another change allowed the arm up to shoulder height; in 1845 the benefit of the doubt was declared (as usual) against the bowler; and in 1864, the grand overlords of the game finally succumbed and declared over-arm bowling legal.

But then a funny thing happened, and kept happening for years. Rather than open the floodgates to a new breed of super-fast bowling tyrant, the dominant form of bowling right up to the interwar period became something the like of which we hardly see in today’s game, to the detriment of fans and players alike. In the late Victorian period, all the most successful bowlers in the game were those who, rather than submit to an illusory need for speed, decided they could have the best of both worlds. They bowled spin, but at medium pace.

In England, three dominated: WG Grace, AG Steel, and George Lohmann. In Australia, a further three stood out: FR Spofforth, Monty Noble and Hugh Trumble. Each in turn pre-empted the rise, and extraordinary success, of the most complete bowler that ever lived, that cantankerous English rascal Sydney Barnes. He too was a medium-paced spinner. In fact, if you look to see who has the best career averages and best strike-rate in Tests, you’ll alight on Lohmann and Barnes. All of which rather begs a question. If medium-pace spin was so effective, why on earth did it die out?

Before answering that question, it may be worth establishing the credentials of these bowlers, by focusing briefly on Barnes who, understood in the proper context, is really their apogee. The dashing county player Jack Meyer said Barnes was definitely quicker than Alec Bedser, which seems astonishing. My guess is that, depending on the pitch, Barnes would hit around 70 or even 75 mph. If you’re a club cricketer, that’s probably up there with the fastest you’ve faced. CB Fry said of him that: “In the matter of pace he may be regarded either as a fast or fast-medium bowler. He certainly bowled faster some days than others; and on his fastest day he was distinctly fast.”

And yet, as he brought his arm over, Barnes gave the ball an almighty rip. I’m not talking here about using seam and swing to extract cut from the pitch. I’m talking full-on spin, with a couple of special attributes. That is why John Arlott could say of Barnes: “He was a right-arm fast-medium bowler with the accuracy, spin and resource of a slow bowler.” Note that Arlott, who always chose his words carefully, describes Barnes not as medium or even medium-fast, but as fast-medium. And that he was a genuine, even prodigious, spinner of the ball is evidenced by Barnes’ account of an extraordinary meeting with Noble.

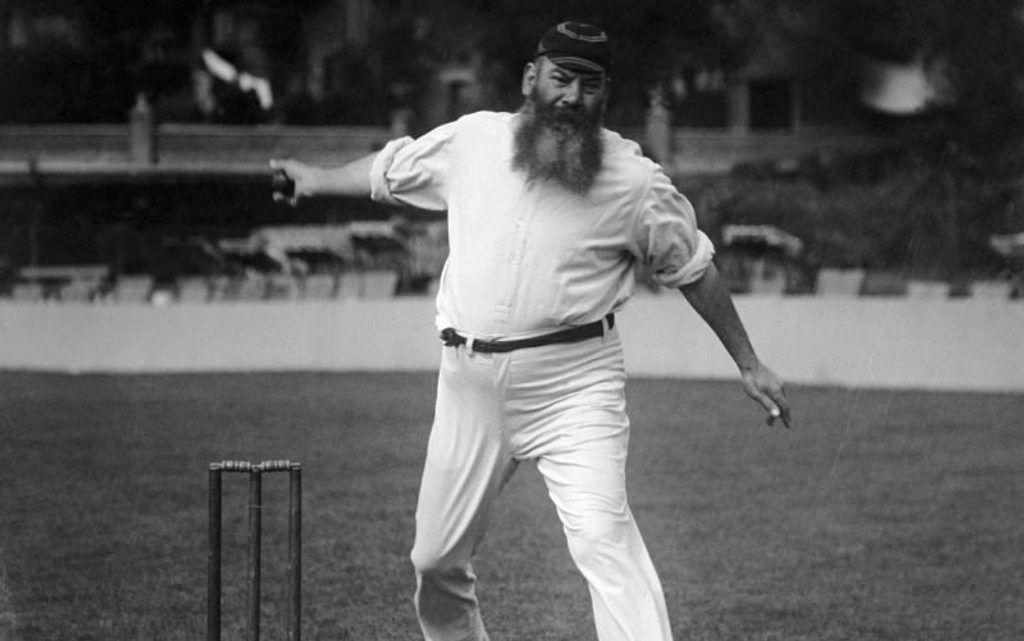

WG Grace: King of the swingers

WG Grace: King of the swingers

Twirlymen constitute a special breed within cricket, a fraternity that bestows special privileges on its members, and through the ages spinners have met with each other to pass on the wisdom they have gleaned. Shane Warne and Abdul Qadir once sat across a Persian carpet from each other in the latter’s house in Pakistan, spinning oranges hither and thither. Similarly, Barnes said he once asked Noble, “If he would care to tell me how he managed to bring the ball back against the swerve”.

“He said it was possible to put two poles down the wicket, one 10 or 11 yards from the bowling crease and another one five or six yards from the batsman, and to bowl a ball outside the first pole and make it swing to the off-side of the other pole and then nip back and hit the wickets. That’s how I learned to spin a ball and make it swing. It is also possible to bowl in between these two poles, pitch the ball outside leg stump and hit the wicket. I spent hours trying all this out in the nets.”

For such a fastidious man, Barnes is rather lazy in conflating ‘swerve’ and ‘swing’ here. What he means by both is what we today refer to as ‘drift’: the glorious tendency of a spinning ball to move in the air in the opposite direction to the eventual spin off the wicket. Unlike modern spinners, Barnes’ wrist was slightly cocked back at the point of release, as if he was screwing or unscrewing a light bulb above his head (screwing for the off-break; unscrewing for the leg-break). This, for reasons only a better physicist than I could tell you, compensates in accentuated swerve for what it sacrifices in turn off the wicket.

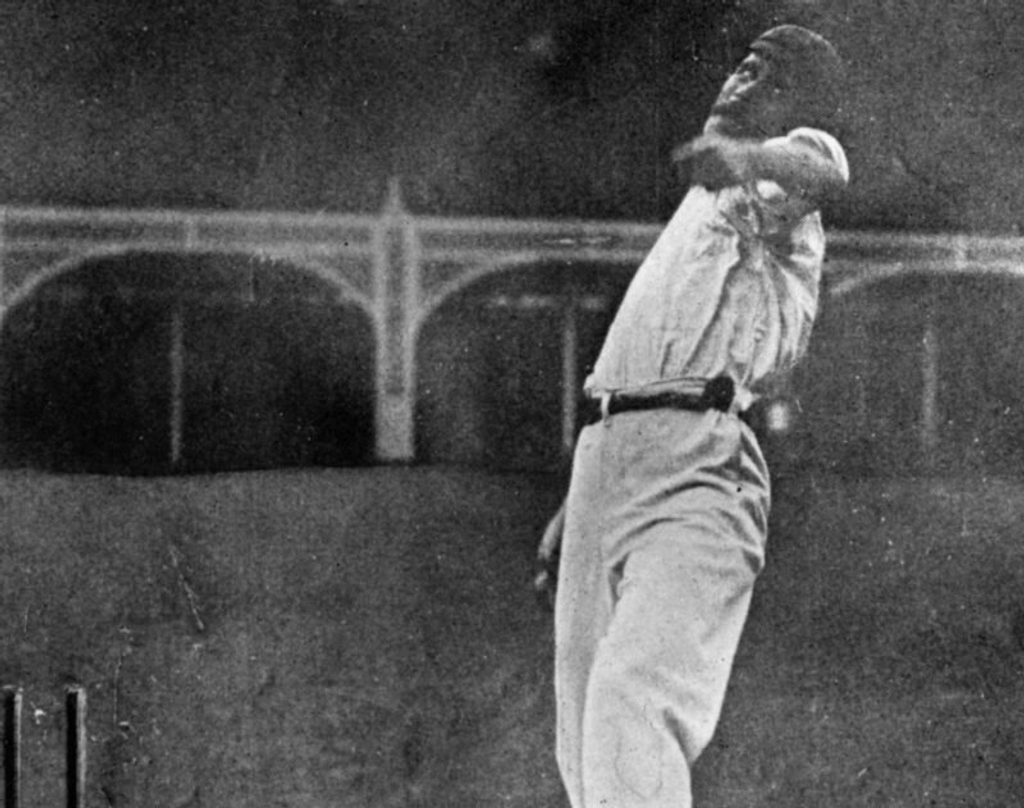

Sydney Barnes: ‘The most complete bowler who ever lived’

Sydney Barnes: ‘The most complete bowler who ever lived’

So the picture we have of the man (above) who took 189 wickets in just 27 Tests at 16.43, with a wicket every seven overs – and a record 49 wickets in four Tests against South Africa in 1913/14 (he refused to play the last Test in a dispute over his wife’s hotel fare) – is of genuine pace and genuine spin combined. He was perhaps quicker, and spun the ball more, than the other swift pioneers of the late Victorian period. But is there any good reason that modern bowlers resolutely refuse to ape Barnes’ astonishingly successful method? My answer is emphatically no.

It’s true that there has been a conspiracy against spinners throughout the course of the game – shorter boundaries, limited overs, bigger bats, video replays (which cost them dearly until Hawk-Eye) came in and, above all, covered pitches. The last of these may partly explain the dwindling of the art. But there are three other possible reasons too: first, fashion; second, modern coaching; and third, sheer laziness.

None of these are forgivable, of course, particularly the needless and harmful conservatism of coaches who insist young players specialise early. Barnes had only three hours of coaching in his entire life. He would scoff at the refusal of fast bowlers to learn the art of spin, and vice versa; and if there is no good reason to keep the two art forms distinct, there must be hope that some brave young bowler could raise the spirit of medium-pace spin from the sporting grave to which it has prematurely been consigned. If he had the wit just to try, and the talent to come into mild success, lovers of the game the world over would be eternally in his debt, for re-acquainting cricket with a once great technique.