One of the most celebrated cricketers of his or any other generation, the enigmatic Wally Hammond moved to South Africa after retiring and tried to make a clean break from his past with a new family.

Luke Alfred explores the melancholic later years of Hammond’s life following a serious car crash and discovers that he kept even his own children in the dark about his previous life as a cricketing superstar.

In February 1960, while driving from his home outside of Durban to Pietermaritzburg, Wally Hammond rolled his car. The accident took place in daylight but the stretch of road was new and unfamiliar: Hammond swerved suddenly to avoid a cyclist, lost control and the car corkscrewed down an embankment. “The story Mom told us was that he always wore very wide trousers with a turn up, and the leg of the trouser was caught under one of the pedals,” says Valerie Guareschi, Hammond’s youngest daughter. “His car door flew open but he was not thrown clear due to the trouser leg being caught. His head hit the ground every time the car turned over. There was a doctor in a car behind on the road coming back from the beach who stopped and wrapped a beach towel around his head. Somehow he contacted St Anne’s Hospital in Pietermaritzburg and told them to send an ambulance but not to hurry. Dad wouldn’t make it.

“Well, make it he did, and doctors said it was due to his physique and fitness, but unfortunately he was a heavy smoker which caused problems with his recovery. The hospital had to tip his bed up to clear his lungs. I remember walking into the ward with Mom and I did not recognise Dad. He had turned white overnight and had stitches from his forehead to the back of his head. Mom said his head had split like a melon.”

Sybil had a cricket net built in the garden so her husband would have something to do once he recovered

Born in 1903, Hammond was already 56 by the time of the accident, and was bed-ridden for almost a year. Roger – Wally and Sybil Hammond’s (neé Ness-Harvey) only son – remembers his mother cutting up coconuts and boiling them to extract the oil before applying it to Wally’s scalp to help restore his hair. Sybil also had a cricket net built in the garden so her husband would have something to do once he recovered. An intensely practical woman, she used to place cups of tea and glasses of water just out of reach to encourage Hammond to use his wasted muscles. “He would shout and swear at her but she never moved those cups and glasses closer,” remembers Valerie. “It got him going. After Dad’s terrible accident, Mom was amazing. She dedicated herself to him. He was virtually paralysed.”

An inveterate womaniser when young, Hammond probably met Sybil, his second wife, while captaining England on tour of South Africa in 1938/39 – the series that launched the ‘Timeless Test’ into cricketing folklore. Sybil’s father was one of Natal’s youngest-ever barristers when he passed the bar and subsequently went on to found the Law Faculty at the University of Natal. Her older brother, Maurice, was an energetic club cricketer who played the odd match for Natal ‘B’. Family members suspect it was he who introduced his sister to Hammond.

Hammond offers a cigarette en route to Australia for the Bodyline tour in 1932

Hammond offers a cigarette en route to Australia for the Bodyline tour in 1932

Blonde and tall, Sybil was a beautiful Natal socialite who was crowned ‘Miss Hibiscus’ in the prelude to a Miss SA Beauty Pageant before World War II. During the War, Hammond was based in Egypt and he frequently took leave or convalesced in Durban rather than returning to England to be with his first wife, Dorothy Lister, from whom he was estranged. After the War he and Sybil attempted to live in England but she was unhappy and wanted to return home. Hammond’s first marriage was annulled and, fearing the disapproval of his mother, Sybil quickly changed her name from Ness-Harvey to Hammond by deed poll.

Once settled in Durban, Hammond secured a position at Denham Motors working for a local tycoon by the name of Norman Marshall. Times were good for the family. They lived in a fine home in Hillcrest, with a retinue of “chefs and housemaids”. Valerie – born in 1952, two years after the eldest daughter Carolyn, who was born two years after Roger – remembers having her own nanny, while Roger recalls sneaking into the in-house pub where the Hammonds entertained a small circle of regular guests.

Roger and Valerie both claim not to have known at the time that their dad had captained England. Valerie remembers a cupboard of white linen shirts and Roger recalls a boomerang brought back from Australia and the occasional item of memorabilia, but nothing more. Their father playing for and captaining England, participating in the Bodyline series and being the best batsman in the world until Don Bradman stole his thunder were never discussed.

Dad tried to forget his career as a famous cricketer I think – he never mentioned it

The children were not encouraged to express opinions and were left very much to their own devices, the family occasionally gathering around the radiogram to listen to an episode of Mark Saxon and the Creaking Door. Both parents were stern but distant. For the most part Roger found his father “mean as all hell”, while Valerie was awestruck by his powerful frame and enigmatic silence. “Dad tried to forget his career as a famous cricketer I think – he never mentioned it,” she says. “My parents only had a couple of very close friends and cricket was never mentioned. His friend’s son was a promising golfer and they seemed to chat quite a lot about that in the evening.”

It wasn’t easy tip-toeing away from such an illustrious past. Hammond was sporting royalty through the late 1920s and well into the 30s. His first wedding was covered by the British Pathé cameras, and his exploits on both sides of the picket fence were dissected and cheerfully exposed.

Boys of all ages grew up mesmerised by the famous image of Hammond taken by the Australian agency photographer Herbert Fishwick in a game played between MCC and New South Wales at the SCG in 1928. Taken from a slightly raised position beyond the boundary ropes at third-man, the photo shows Hammond cover-driving with perfect poise. Neil Harvey, the great Australian left-hander, taped the photograph to his mirror when he was growing up, and doubtless many others the world over did the same thing. On that tour Hammond solidified his reputation as the pre-eminent batsman of his generation, inpsiring England to a 4-1 series win, plundering double-hundreds in Sydney and Melbourne and scoring a hundred in each innings at Adelaide. His series aggregate of 905 runs remains the highest by an England batsman against Australia.

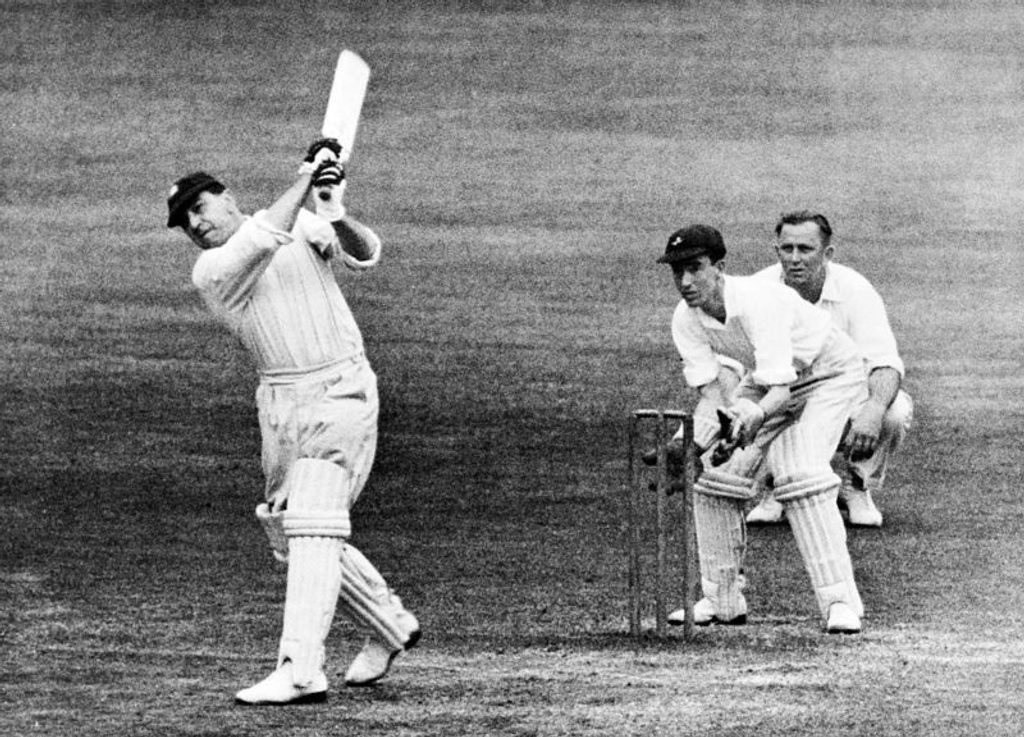

Hammond on his way to a century at Lord’s in 1945

Hammond on his way to a century at Lord’s in 1945

Despite trying to flee from his past, there were constant little reminders of his lingering fame from neighbours, well wishers and hangers on – he was only employed by Marshall because of who he was. Hammond played no administrative role in the cricketing affairs of his new province, though, and played social cricket only occasionally. He wasn’t a regular at Kingsmead, the closest ground, and didn’t comment on the cricketing affairs of the day other than having three books ghostwritten under his name.

All the evidence suggests that in South Africa he mired himself in a kind of willed forgetfulness. “He still had a first-rate cricket brain,” remembers John Watkins, one of several all-rounders in the South African side Jack Cheetham took to Australia in the early 1950s, drawing the series 2-2. “I remember bowling in a scratch game and he was on the fielding side. ‘Why are you bowling to two slips at your pace?’ he asked me. Take out the second slip and put him in the gully – that’s what you need to do’.”

***

Hammond’s accident was catastrophic for the family. It roughly coincided with the loss of his job at Denham Motors and the family were forced to sell their Hillcrest home. A cousin owned the Field’s Hotel in Kloof where they stayed temporarily, before managing to buy a far smaller house in Park Lane. Wally, frustrated by his lack of mobility, slipped into the melancholy that had plagued him at times before the War.

Valerie remembers a weekly ritual during this period. Every Sunday morning her father would head down to the local tearoom to buy the papers and a fruit cake. Desperate for her father’s attention, she would watch him consume the cake, slice after tantalising slice, hoping for one herself. Oblivious, he flicked through the newspaper while she knelt like an expectant puppy at his feet, the cake slowly disappearing until there were only crumbs. The paper was folded and put away, with the child barely acknowledged.

Luckily Owen Horwood, a family friend and later Minister of Finance under South Africa’s Nationalist Government, stepped in and offered Hammond a coaching role at the University of Natal. Under different circumstances the overture might have been rejected but Hammond had no choice. And so began the final chapter of his cricketing career, where he coached a very good university team by saying very little and watching carefully, making it count when eventually he had something to say.

He coached by saying very little and watching carefully, making it count when eventually he had something to say

Peter Muzzell, captain of a strong Natal Universities team in the early 1960s, remembers a long train trip across the veld to an inter-varsity tournament in Cape Town – following the same route the England team would have taken after the ‘Timeless Test’ – where he asked to sit in Hammond’s couchette and pick his brain. Beneath the withdrawn exterior Muzzell found a deep cricketing intelligence, although he notes that Hammond was quick to dismiss the unorthodox. “He didn’t like [Eddie] Barlow, who was playing for Wits [University] at the time,” says Muzzell. “Said he was far too loose.”

In the years after the accident, life slowly returned to normal. Valerie remembers her mother and father as united in their attitude towards parenting but strangely removed from one another: he read while she worked in the kitchen or garden. They smoked heavily, drank beer off the shelf and slept in separate bedrooms. There were no overt displays of physical affection, few celebrations and even fewer family gatherings.

Hammond in 1936

Hammond in 1936

Life unspooled in steady rhythms. The emotional environment was austere. “If you didn’t finish your breakfast you had it for lunch,” recalls Roger. “If you didn’t finish it at dinner, you had it for breakfast the following morning. They were tough measures. When we put our elbows on the table she used to walk around and tap the back of our elbows with a little knife.”

Hammond didn’t seem to notice much, being by far the less active of the two parents. He seldom reciprocated Valerie’s adoration and, although kinder to Roger, was only present in a blurry, half-formed way. He encouraged Roger to enjoy school – “The best days of your life” – but did so distantly. He was never heavy-handed or raised his voice, leaving the physical discipline to Sybil, who could also be thoughtful and kind.

Many years after Hammond’s death, from a heart attack in 1965, Sybil found work in a boutique on Durban’s Musgrave Road. Valerie had moved out of home by that stage and was living in Johannesburg. “Every month I would receive a parcel with a coat, or shoes and bag, and then to follow the outfit to go with it,” says Valerie. “Mom really was a very elegant woman and had a good eye for fashion. I loved receiving those parcels. I don’t remember at what stage she left the boutique but I do remember that all three of us chipped in every month to assist her as her pension came to nothing. She died lonely and without a cent.”

Once, in happier times before Wally’s accident, both parents combined to celebrate a special Christmas, one Roger has never forgotten. “I believed in Santa Claus until I went to Murchison Prep when I was about seven or eight,” he says. “When we were all asleep one Christmas Eve in the Hillcrest house they dug two furrows across the lawn and threw horse manure all about – that was for the horses and sleigh, of course. In the morning we heard a little bell and there were presents waiting. That was special. It was the one and only time they ever did it.”