On the day Denis Compton would have turned 100, Jonathan Liew looks at the legacy created by the first superstar of cricket’s television age.

Jonathan Liew is a regular columnist for Wisden Cricket Monthly.

The story goes that one day Denis Compton handed his friend, the legendary sports journalist Reg Hayter, a suitcase full of unopened mail he could not bear to deal with. When Hayter opened them, he found a letter from the News of the World, offering Compton the handsome sum of £2,000 a year to write a column. Later in the same stack was another, curter letter from the same newspaper, explaining that some time had passed without a reply, and so the offer was being withdrawn.

“Denis,” Hayter told him, “you want looking after.”

Denis Compton signs his autograph for photographer Ronnie Pilgrim

Denis Compton signs his autograph for photographer Ronnie Pilgrim

So Hayter introduced him to a businessman called Bagenal Harvey, who in turn introduced him to the Royds advertising agency, who represented a brand of hair products called Brylcreem. And thus was forged the legend of Denis Compton, a man who would become the first superstar of cricket’s television age, and whose fusion of the sporting and commercial would ultimately change the game forever.

One hundred years after his birth, and seven decades after his golden prime, it’s tempting to wonder what remains of Compton’s legacy today. His record of 3,816 runs in a season, scored in 1947, feels so distant and unmatchable as to be essentially irrelevant. The majority of his great innings were never captured on film. And the spirited tales of bravado and aggression he inspired can occasionally seem – in an age of Dilscoops, towering sixes and 12-an-over chases – just a little ‘tame’.

Yet in his own way, and his own time, Compton was a pioneer. His partnership with Harvey made him the first cricketer to have an agent, and a decade later the pair would team up again to establish the International Cavaliers, the all-star travelling team that can be seen as a precursor to today’s riotous, entertainment-driven Twenty20 circuses. In opening cricket’s doors to the world of brokers and intermediaries, and in exploring the limits of his own commercial worth – Brylcreem, Slazenger, Watney’s Red Barrel beer – Compton set in motion a phenomenon that would ultimately see its fullest expression in the modern franchised freelancer: the cricketer-as-brand.

Of course, there was a lot more to this than money, or even fame: Compton was by no means the first celebrity cricketer. Yet unlike Grace or Bradman, whose renown was essentially inseparable from their athletic prowess, Compton became a celebrity in his own right. His private life, and particularly his acrimonious divorce in 1950, became fodder for the newspaper gossip columns. And away from the crease, he carefully cultivated – or more accurately, had cultivated for him – the character of the chuckling cavalier, the debonair playboy who would arrive at the ground still dressed in his dinner attire from the night before.

What was happening here, essentially, was the making of a myth. The image – the fine silk shirts, the immaculately creamed hair, the pristine dinner suits – was but one part of it. The other was the careful positioning of Compton as a national hero rather than simply a sporting one, a ray of light piercing the gloom of post-war austerity, a triumph of English ingenuity, the working-class boy who shed his working-class accent and held a country in thrall. “There was no rationing in an innings by Compton,” as Neville Cardus put it, and it was a motif eagerly pursued in the subsequent years by a generation of writers keen to seal their own sun-drenched, Boys’ Own memories into posterity.

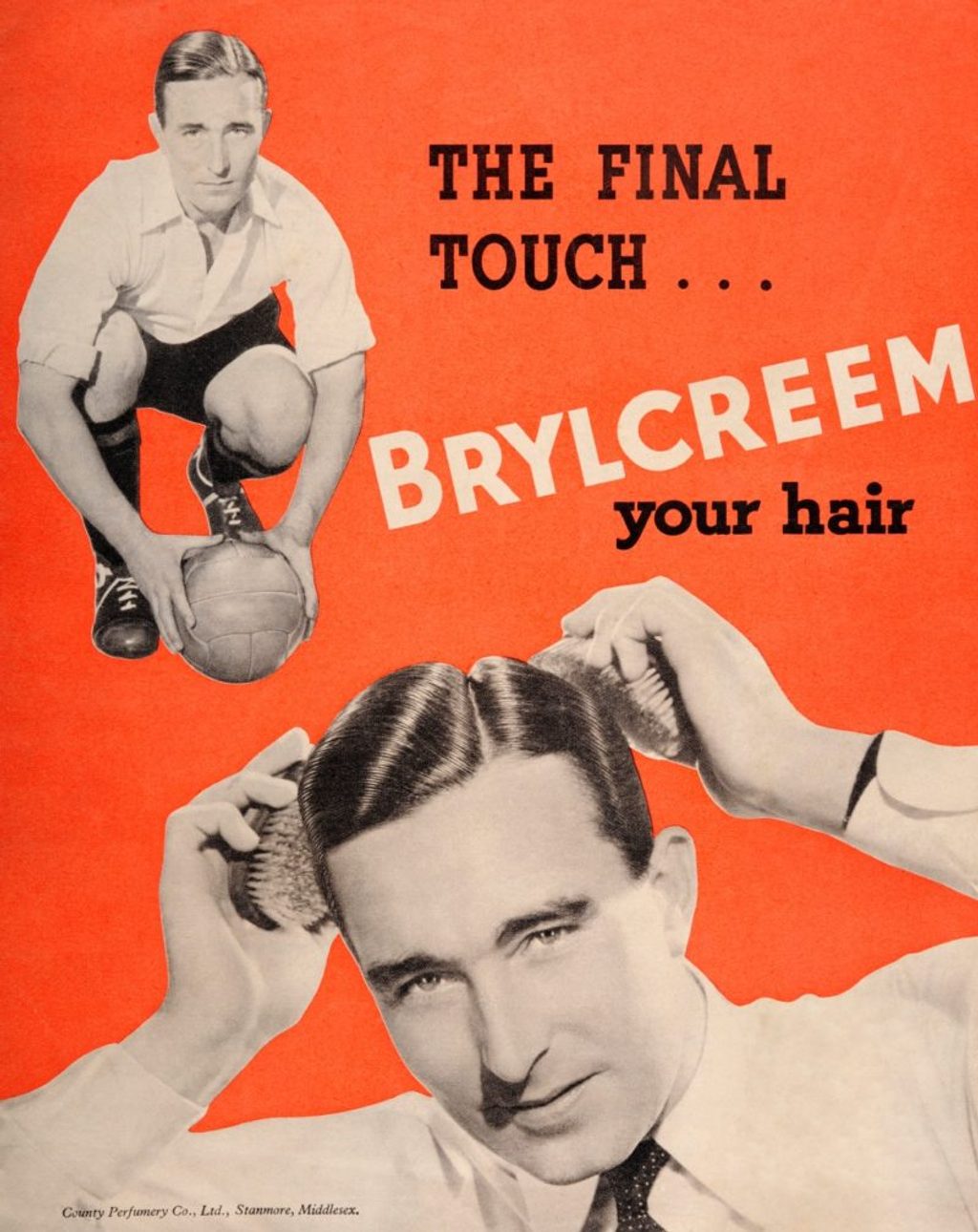

Denis Compton featured on a vintage advertisement for Brylcreem published in 1950

Denis Compton featured on a vintage advertisement for Brylcreem published in 1950

How much of this tale was genuine, and how much confected? It’s hard to know for sure. But the ideological subtext of what goes into the Compton myth – and what stays out – is hard to ignore. When he died in 1997, the obituarists justifiably waxed on about the dashing batsman, the absent-minded genius, the bon viveur. Most, however, failed to mention his frequent statements in support of apartheid South Africa, a cause he pursued long beyond the point where it was fashionable or even acceptable. As the sports historian Professor Jeffrey Hill puts it: “The Compton legend was a comforting, reassuring image of what Britain could achieve by reasserting essentially conservative values.”

The Compton we remember today is thus essentially a palimpsest, a collage of various evocative pictures and memories, many of which have been placed in our eyeline for that specific purpose. And as we survey the current breed of stage-managed cricketing celebrities, with their PR strategies, premature autobiographies and fistfuls of endorsements, we can observe that in this respect, too, Compton was well ahead of his time.