The Adrian Shankar Files, part one, by Scott Oliver.

This is the first in a seven-part series, The Adrian Shankar Files. Read the rest of the series here.

In The Adrian Shankar Files, a seven-part series, Scott Oliver delves deep into new material about a player who, in May 2011, was fired just 16 days after signing for Worcestershire when it was discovered that his age and the tournaments he claimed to have played in had been fabricated. We will see in detail how Shankar attempted to land an IPL contract with the help of radical bat brand Mongoose, who saw him as the perfect marketing vehicle in their attempts to crack the Indian market, as well as the methods used to secure his Worcestershire deal.

Part one is a recap of what we know so far, including mysterious attempts to create websites and edit Wikipedia to support the existence of the Mercantile T20 tournament, a competition which purportedly took place in Sri Lanka and in fact never happened.

***

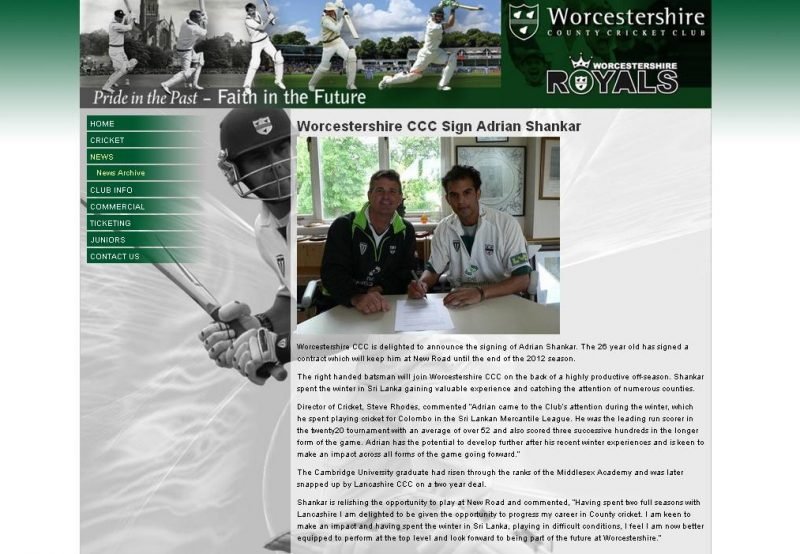

Ten years ago today, a 29-year-old Cambridge University law graduate who had never played a First XI county match sat in the quaint old pavilion at Worcestershire CCC’s idyllic New Road ground posing for a photograph with the club’s Director of Cricket, a contract (presumably just signed) sitting on the table in front of them. For a person whose dreams had just become reality, he appears more anxious than happy, as though overwhelmed by the enormity of the moment, the ramifications of it all.

The Worcestershire CCC website announcing the signing of Adrian Shankar

The Worcestershire CCC website announcing the signing of Adrian Shankar

On the surface, it is an unremarkable image, an archetype staged to service basic publicity requirements, two men smiling (or trying to smile) as they are about to embark upon what they hope will be a fruitful professional adventure. On the surface.

This is how the Worcestershire website announced the news, how they framed the image:

Behind that image, in the innermost thoughts we can only guess at, things were very different. Because as Adrian Anton Shankar posed for the camera alongside his new boss, pen in hand, he was acutely aware, no matter how far from his conscious thoughts he tried to push it, that he was only sitting where he was because he had perpetrated a colossal act of deception. Not that Rhodes was entirely blameless.

The words attributed to ‘Bumpy’ Rhodes in the press release describe a tournament that never took place, a pure fiction. But there it is in black and white, the assertion that Worcestershire had been monitoring his progress in Sri Lanka and details of the success he had had. Let us call it an oversight in due diligence. But one of the curious realities behind that image – in among the small talk of that day, the conversations about how tough Shankar had found conditions in Sri Lanka, how he was looking forward to progressing his career – was exactly how that press release came to be written and how it came to be Worcestershire’s official statement. Neither Rhodes nor David Leatherdale, the chief executive at the time, is prepared to answer questions about the episode. The club’s then chairman, Martyn Price, says “it was all swept under the carpet” and confirms that nothing was ever explained to the Worcestershire membership.

As with so much about Adrian Shankar’s story, there is a large amount of embarrassment and thus a resolute silence from those who were taken in, almost an omertà, leaving us with a Rumsfeldian mixture of known knowns, known unknowns, unknown knowns and unknown unknowns. What we do know, though, is that almost six years before the Trump presidency, around the time the Kremlin began ‘weaponising’ misinformation for geopolitical ends, cricket had its own bespoke post-truth story. And we know, broadly speaking, how things unravelled at New Road, how it all went pear-shaped for Shankar with the Pears.

We know that, ten days after his 29th (not 26th) birthday, seven days after signing – having told new colleagues Alan Richardson and Jack Shantry at nets that, during the winter, he had hit five sixes in one Rangana Herath over (Herath confirms that no one ever did this to him in his career) – Adrian Shankar played his first ever professional match, a televised CB40 game against Middlesex at Lord’s in which, opening the batting with Moeen Ali, he was bowled by Tim Murtagh for a third-ball duck.

We know that, three days earlier, having spent his first three days on the staff up at Edgbaston getting to know his new teammates, Shankar played a second-tier Birmingham League game for Evesham alongside Steve Rhodes’ son, George. As Worcestershire were going down to a 218-run defeat to the Bears, their fifth loss from five Division One games, Shankar opened the batting with Tom Kohler-Cadmore at Bromsgrove and made four.

We know that, prior to signing for Worcestershire, Shankar’s 12 first-class appearances had all been for Cambridge University or Cambridge UCCE (where they combine with Anglia Ruskin University), for whom he had averaged 19.2, a figure significantly boosted by an innings of 143 in his maiden Varsity game against an Oxford University attack described by Cambridge coach Chris Scott as “unbelievably bad”. Without that innings, his first-class average would have been 12.68. Given that he had started that first University season with scores of 6, 2, 15, 0, 0 and 1 against the counties, it is fair to assume the century played a significant part in him being elevated to the Cambridge University captaincy, which he held for two years.

We know that, the day after his duck against Middlesex at Lord’s, Shankar made his first ever appearance in the County Championship, against Durham at New Road, and that he fielded for five sessions as the visitors racked up 587-7d, coming in at the back end of the day at 50-4 to face Ben Stokes. We know that he survived until the close – initially alongside Moeen until he nicked off to Steve Harmison, then with fellow Mongoose-sponsored player Gareth Andrew – making 10 not out from 60 balls, including a pair of swept threes off Ian Blackwell. “Harmison was bowling a decent spell,” recalls Andrew. “As soon as the Durham boys saw [Shankar’s] technique – he did not want to come forward and when he did it went over his head. He just looked so out of his depth. It was a bit scary. It was a bit embarrassing to be at the other end – they just took the piss out of him for half an hour.”

We know that, after a night to process this experience, Shankar didn’t resume his innings the following morning due to a ‘knee injury’ sustained during the warm-up. “We were doing ground fielding,” says Andrew, “going from side to side and throwing it at the stump, and he threw one and just went down in a sack and that was it, he couldn’t get up. I had to stretcher him off with a few of the other guys. He said his knee had gone. I think it was a running joke that Harmison had shit him up that much that he didn’t fancy it anymore.”

We know that, later that Friday, David Leatherdale – a teammate of Rhodes’ at Pudsey St Lawrence in their Bradford League days and right through several hundred games for Worcestershire – was alerted to the discrepancies in Shankar’s story: chiefly, that a quick check on Google showed that the Sri Lankan T20 tournament on the back of which they had signed him didn’t appear to have taken place, and that several sources indicated he was three years older than was being claimed. We know that his date of birth was mysteriously changed from May 1982 to May 1985 on his Cambridge University CC profile.

We know that a couple of days later, on May 22, as Worcestershire conducted an internal investigation, a rudimentary website appeared purporting to cover the Mercantile T20 tournament. All the edits were carried out by ‘John Winton’ between 10.28am and 6.43pm. The menu tabs included ‘Latest News’, ‘Our Vision’ (a statement from tournament director ‘Ravi de Silva’), ‘Stats’ and a couple of player profiles – for Sachith Pathirana and Adrian Shankar, who, it said, “has an interesting pedigree, becoming one of the youngest ever captains of Cambridge University in 2003 and forming part of one of the first intakes in the Arsenal Academy in Arsène Wenger’s tenure.”

The profile of Adrian Shankar on the Mercantile League T20 website

The profile of Adrian Shankar on the Mercantile League T20 website

There were also scorecards for the two semi-finals: Colombo Reds vs Dambulla Greens and Kandy Blues vs Galle Indigos. We know that, of the 43 players besides Shankar on those cards, a total of 25 could not be traced on the extremely extensive Cricket Archive database, and of the 18 who were genuine players, only eight could feasibly have played as the rest were involved in first-class matches on the dates given for those semi-finals.

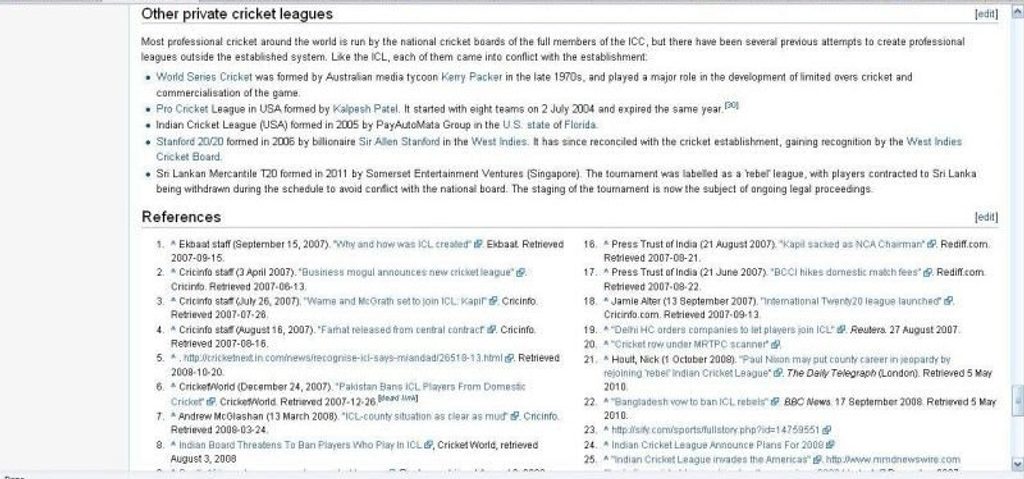

We know that, on May 24, there was an amendment under the ‘Other private cricket leagues’ subheading on the Wikipedia page for the Indian Cricket League, the forerunner to the IPL, which now included a line about the Mercantile T20, claiming it was “formed in 2011 by Somerset Entertainment Ventures (Singapore). The tournament was labelled as a ‘rebel’ league, with players contracted to Sri Lanka being withdrawn during the schedule to avoid conflict with the national board. The staging of the tournament is now the subject of ongoing legal proceedings.” The amendments were carried out by ‘Yperera’ between 11.20am and 11.43am, a user whose only other contributions to Wikipedia would come two days later on the page for Adrian Shankar.

Wikipedia ‘evidence’ of the existence of the Mercantile T20

Wikipedia ‘evidence’ of the existence of the Mercantile T20

We know that, on May 25, the BBC reported that “Shankar faces up to six weeks on the sidelines after scans revealed a strained cruciate ligament” and that, later that day, as Worcestershire’s investigation drew toward a close, a thread dedicated to the Mercantile T20 appeared on the slcricket.com message board, with a link to the recently appeared (and soon to disappear) tournament website. Three users who had registered that same day – ‘tp24’, ‘sangapump’ and ‘lavigne’, none of whom would ever post on any other thread – were able to answer various mysteries surrounding the competition. “Yes, it was a breakaway tournament,” said tp24. “I watched a couple of the games, standard was pretty good, organisation and publicity was terrible.” Sangapump followed up with: “Feel sorry for the players involved. They were duped and have not been paid properly.” And after some further explanation from those two about legal actions, splits in the SLC board, and match-fixing, lavigne would add: “There is a horrible smell of corruption in Sri Lanka, both in government and in cricket. I heard some players are v. scared because of threats from bookmakers and authorities are trying to hush it up.”

We know that, the next day, presumably limping, Shankar was called to New Road and had his contract terminated. We know that he told the Worcestershire chairman that he was being blackmailed by South Asian bookmakers. We know that he said that MI5 had become involved and that they had asked the journalist who broke the story, George Dobell, not to publish. We know that Shankar threatened to sue Worcestershire, but didn’t. We know that Worcestershire passed his registration documents to West Mercia Police, who conducted an investigation and ruled that it was an employment issue between player and club rather than a criminal matter. We know that later that night Yperera amended Adrian Shankar’s Wikipedia page to say that “the [Worcestershire] contract was terminated by mutual consent of club and player after Shankar injured his cruciate ligament.”

We know that Yperera was merely putting his finger in the dyke, however, for in the aftermath of Shankar’s release from Worcestershire there was something of a free-for-all on his Wikipedia page: “According to Adrian he has five Test hundreds, all made while just 15 years old and using a piece of drainpipe … At the age of 12, Shankar represented Ukraine in the long jump in the 2000 Olympics at Sydney, recording a PB of 7.64 metres. He failed to progress to the finals and it later emerged that Shankar was not Ukrainian, but had forged passports in order to join the team. It was therefore surprising when he appeared as the Norwegian hockey goalkeeper four years later in Athens.” There was plenty more, and the gleeful amateur satirists also got stuck in on Twitter, using the #shankarfacts hashtag.

Adrian Shankar’s vandalised Wikipedia page

Adrian Shankar’s vandalised Wikipedia page

We know that, over the coming days, more and more stories emerged of Shankar’s fabulations and fabrications. Luke Sutton, a colleague on the Lancashire staff for two years, told in the Daily Mail of how he confronted Shankar over rumours he was three years older than he claimed. “His reply, straight to my face and without a shadow of doubt, was that he had been on a life support machine for the first three years of his life and was therefore physically three years younger than he should be. I challenged him on this and said that surely he grew during the three years on the life support machine. He simply replied ‘No, I didn’t’ and walked off.”

We know that, not long after signing with Lancashire, the Manchester Evening News published an interview with Shankar (Textbook cricket for Shankar) in which he said he was studying for a part-time Masters in International Relations, with the designated six weeks of tutorials per year – apparently delivered in two-week blocks in October, February and April – brought forward so that he could concentrate on his cricket: “Monday to Friday I will be doing whatever we are doing in the morning, whether that be netting or training, then in the afternoon I tend to set up in the dressing room to get to work on my thesis or whatever I need to be doing.” We spoke with several Lancashire colleagues from that season and none of them ever saw him studying.

The MEN interview also reported that Shankar had put his cricket on hold for 18 months due to a bout of glandular fever, yet we know there is no 18-month period in which he doesn’t play cricket. In fact, in the three years between his final game for Cambridge University and first game for Lancashire IIs he was playing for Spencer in the Surrey Championship, averaging 16.71 in the Premier Division in 2008 and 23.63 across 32 innings in the second tier in 2006 and 2007, with his top score in both those seasons coming against relegated clubs. MEN also reported that he had been in the national tennis squad as a teenager. This is also untrue – although he did have a tennis court at home when growing up – as was the claim about the Arsenal Academy, something that baffled the Lancashire players when they saw him in football warm-ups.

We know that Shankar signed for Lancashire in November 2008 after a short trial period comprising four Second XI three-day games in which his contributions were: 39 not out against Derbyshire, 19 against Northants, ‘absent hurt’ in both innings against Durham at South Northumberland CC after collapsing while retrieving a ball from a neighbouring garden out of sight of colleagues, and finishing with 46 against Surrey. We know that when the signing was announced, Lancashire’s Director of Cricket Mike Watkinson said that Shankar, averaging 19.2 in first-class cricket, had “attracted interest from a number of other counties, which confirms his potential.” (Sometimes you just get a feel for a player, particularly if a number of other ‘respected judges’ are singing their praises.)

We also know that Chris Scott, the Cambridge University coach whose opinion was sought by neither Worcestershire nor Lancashire, had to ask the latter to remove from their website a quote attributed to him referring to Shankar as one of the finest young players seen at Cambridge since John Crawley. And we know that, when the registration was going through, Pip August, the secretary of Bedfordshire CCC – for whom Shankar had played 21 Minor Counties Championship matches between 2000 and 2006, scoring 1002 runs at 27.83, with three fifties and one hundred in 38 innings – contacted Lancashire to tell them that Shankar was born in 1982, not 1985. And we know that nothing was done about it, by the county or the ECB (which goes a long way to mitigating Worcestershire’s oversight on this particular falsehood).

We know that, at the start of the 2008 summer, on May 8, more than three months before his Lancashire trial, Shankar played a game for the Duke of Norfolk’s XI at Arundel, telling acquaintances in the side from his university days who had enquired what he was up to that he was “on the playing staff at Lancashire, actually. There’s no Second XI game this week and, with Flintoff maybe missing next week, apparently I’m in with a shout of playing in the Championship in the next game, so I thought it would be good to get a game in here.”

A South African on the Duke of Norfolk’s XI asked about Faf du Plessis, then playing as a Kolpak at Old Trafford. Shankar replied: “Yes, he’s a good player – bats and bowls some medium pace as well.” One of those university acquaintances was bemused by the reply – among other things, du Plessis bowled leg-spin – and, after the match, put in a call to his friend Faf, who confirmed he had never heard of Shankar. (On the subject of Kolpak players, a plausible reason for Shankar shaving three years from his age when signing for Lancashire was that the ECB, unable to legislate against counties picking players from countries that had third-party agreements with the EU and which were thus subject to the same labour laws, were instead offering the positive incentive of payments for every appearance by an England-qualified player of 25 or younger as a workaround.)

Curiously, however, when Shankar’s signing was announced on the Lancashire website on November 26 that year, it stated: “Adrian spent some time with Lancashire during the 2008 pre-season period. He then spent the first half of the season playing for Kent’s Second XI.” We know that neither of these claims are true. Shankar had played six Second XI Championship matches in the seven years between starting university and trialling at Lancashire – none of them for Kent, and none in 2008 – in which his scores were 10, 41, 1 not out, 1, 2, 13, 6, 5, 14 and 12.

We know that Shankar attended Bedford School, where he played alongside Alastair Cook. We know that he went up to Cambridge in September 2001, aged 19, and that he graduated in summer 2004. After that year’s four-day Varsity match at the Parks, in which he was dismissed lbw from the very first ball of the game, Shankar told assembled teammates and opponents in Oxford’s Bridge nightclub that his post-university plans were to consider his job offers: working for either the UN or World Bank in New York or Geneva.

However, the following spring, to the surprise of the Oxford team, Shankar appeared in some early season games for Cambridge. One of Shankar’s teammates, replying to a query from the Oxford camp, said: “Yes, Shanks is back around! None of us really knew that he was still in Cambridge, but apparently he’s doing some legal research that makes him eligible to play Varsity.” In fact, eligibility rules were that you had to be a full-time student in residence. Nevertheless, despite scepticism about this story, and the unlikelihood that Shankar had been in Cambridge for two terms without any of his former teammates knowing about it, Oxford did not take the matter further, if only because they did not feel Shankar’s presence would disadvantage them. (While many subsequent reports would state that “Shankar first came to prominence at Cambridge,” the fact was that in both 2004 and 2005 he only played one of the three first-class UCCE games against the counties, for reasons of non-selection.) As it turned out, due to an unspecified injury sustained while fielding, Shankar batted down the order in that 2005 Varsity match for which he was almost certainly ineligible, scoring a duck in the first innings at number nine and 11 in the second at number eight.

We know a lot about the Adrian Shankar story, then, but not as much as we don’t know. Chiefly, we don’t know what his motivation was. We know that he desperately wanted to become a professional cricketer, but we don’t know why he went to the lengths he did, why he couldn’t see the inevitable endgame. The only person who can answer that is Shankar, and the chances are that he doesn’t really know since we humans are often mysteries to ourselves and such insight would require a degree of self-awareness that his actions – the spinning of more and more elaborate and far-fetched lies, all the way to the point at which, talk having been talked, walk needed to be walked – would indicate he was lacking.

At any rate, we know now about this long list of falsehoods, but we didn’t know much about it at the time he was sat in the old pavilion at New Road, innocently photographed putting pen to paper, shooting the breeze with Steve Rhodes. What we also didn’t know until now was that a stint in county cricket may have been slightly disappointing to him, that it was very much second choice. We didn’t know then that Adrian Shankar, with the enthusiastic help of Marcus Codrington Fernandez, CEO of his bat sponsor Mongoose, had spent that winter between Lancashire and Worcestershire trying to break into the IPL, first via the conventional route of the player auction (base price: $20,000) and, after that, through the more unorthodox post-truth methods that would ultimately open the door for him at Worcestershire.

This was an email sent by Codrington Fernandez to Dermot Reeve, assistant coach to Geoff Marsh at Pune Warriors, in December 2010, four months after Shankar had been released by Lancashire:

What is true in this, besides his stats being dreadful, was that Mongoose did receive a lot of articles about Shankar. All of them were pasted into the body of emails. None of them came with links to the original source. None of them had photos. None of them had scorecards. All of them had ‘journalists’ in the bylines who could not be found to have written anything else about cricket, where they could be found at all.

And yet all of them were blithely forwarded to IPL VIPs – coaches, captains, owners, scouts, agents – by the CEO of a cricket brand whose entire business strategy was based on cracking India, and who saw Adrian Anton Shankar as a key element in that effort.