As a cricketer Ben Stokes has the potential to follow in the footsteps of Grace, Botham and Flintoff. But he’s unlikely to become a national icon, writes Wisden Cricket Monthly columnist Jonathan Liew

This article first featured in issue 15 of Wisden Cricket Monthly. Subscribe here

Ben Stokes may be the fourth great English all-rounder. That was certainly the impression from watching some of his recent performances in Sri Lanka, a series in which – in common with many champion cricketers – his contribution seemed to defy raw numbers, defined instead by the classic unquantifiables of timing, showmanship, pure athleticism, and an uncanny ability to pick up key wickets with rank long-hops.

England has, of course, been particularly fortunate in this regard. We can define a great all-rounder as a player who not only displays a mastery of all three disciplines, who not only does so at the highest level, but leaves a broader imprint, who somehow bequeaths a subtly different game to the one he picked up.

Few other countries can boast more than one or two: Australia have Noble and Miller, the West Indies Sobers and Constantine, South Africa Kallis and Procter and perhaps Aubrey Faulkner. But in Stokes, England have unearthed a player who – given a fair wind – will eventually stand alongside the existing triumvirate of Grace, Botham and Flintoff.

The story of England’s four great all-rounders is partly a saga of yeoman triumph over establishment orthodoxy. To read of how Grace reinvented the art of batsmanship, or how Botham smashed the glass ceiling of ambition and audacity, is to identify a genuine narrative thread between these four burly provincial boys with their agricultural strength, box-office instincts and distaste for convention.

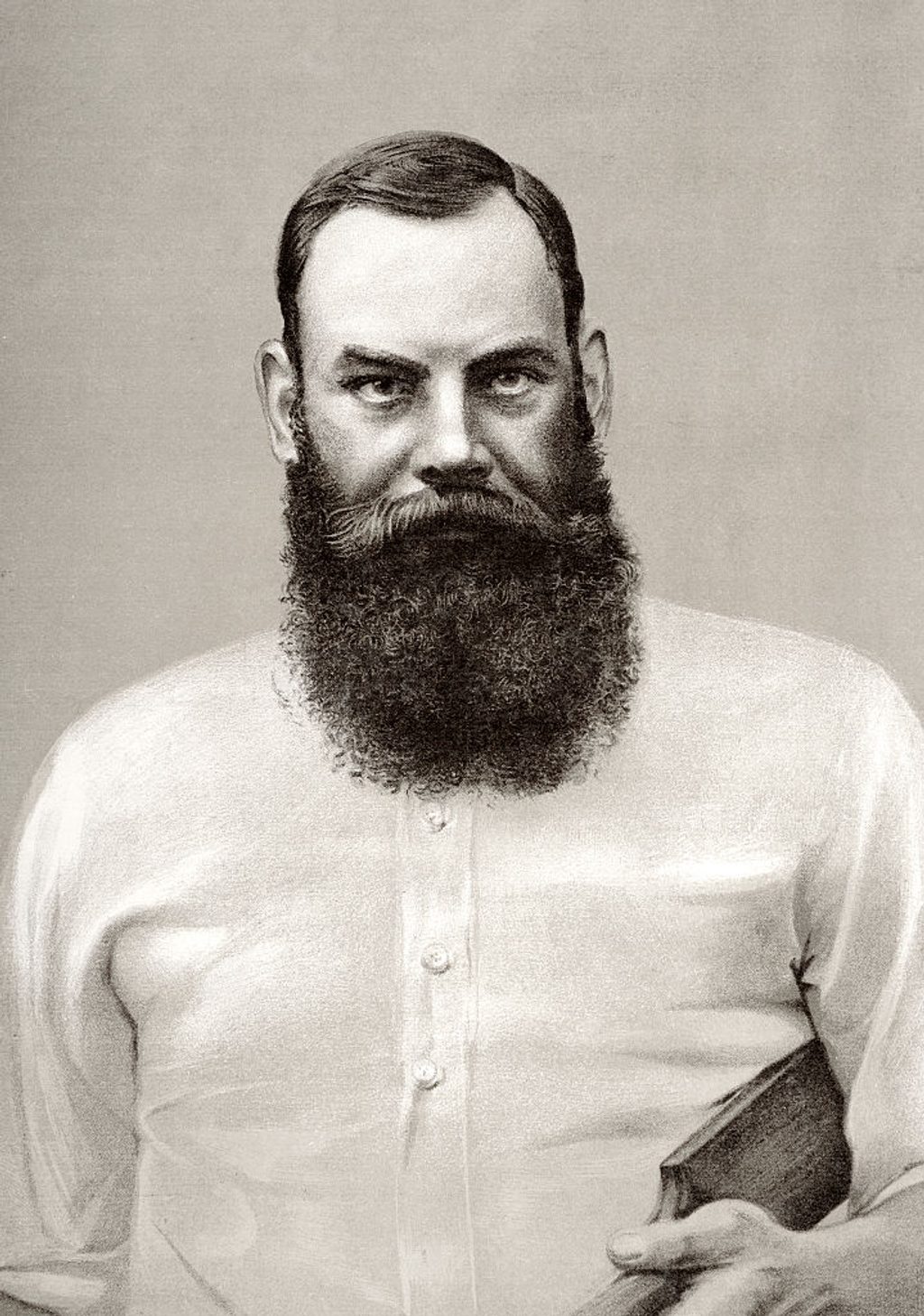

A vintage illustration of England cricket legend WG Grace, circa 1895

A vintage illustration of England cricket legend WG Grace, circa 1895

Yet in this quartet can be traced a different story, too: the dimming of English cricket’s light bulb, the waning of its resonance, its retreat into the national margins. The 150-year journey from Grace to Stokes is also a tale of decline.

Grace’s celebrity can often be overdone; there’s little evidence, for example, to support the oft-cited claim that his fame was outstripped only by William Gladstone and Queen Victoria. What is certainly true is that he enjoyed a cultural cachet that reverberated far beyond the confines of his sport. During his Indian summer of 1895, a benefit fund attracted donations from both the prime minister Lord Rosebery and Lord Salisbury, the leader of the opposition.

Grace’s unmistakable features were used to sell everything from soap powder to life insurance. Indeed, his biographer Richard Tomlinson considers him “the first truly modern international sports star”. For CLR James, he “enriched the depleted lives of two generations, and millions yet to be born”.

Ian Botham’s exploits in the 1981 Ashes series earned the all-rounder legendary status

Ian Botham’s exploits in the 1981 Ashes series earned the all-rounder legendary status

In August 2018, in Grace’s hometown of Bristol, a judge called Peter Blair was interviewing potential jurors ahead of the criminal trial of Stokes for affray. “Are any of you an extremely committed cricket follower?” he asked. “Does anyone fall into the category of having an extreme passion for the sport?”

Nobody came forward. Blair then asked if anybody knew either of the defendants, Stokes or Alex Hales, or any of the list of potential witnesses in the case. Nobody did. It was a verdict as quietly devastating as any the jury would later issue. And in a sense, the Stokes trial was its own sad window into the diminished status of English cricket and its cricketers. “The ginger one offered me £60,” testified Andrew Cunningham, the bouncer at Mbargo nightclub, during the trial. “I didn’t know they were famous.”

Ben Stokes leaves Bristol Magistrate’s Court on February 13, 2018

Ben Stokes leaves Bristol Magistrate’s Court on February 13, 2018

It’s hard to imagine such a statement being uttered about Botham or even Flintoff. A generation after the retirement of the former and a decade after the retirement of the latter, these two remain this country’s two most recognisable cricketers, its last real stars of the terrestrial television age. A criminal case involving Flintoff or Botham would have been the trial of the year, perhaps even the decade; with Stokes, even the initial dribbles of interest eventually congealed away after a few days.

Andrew Flintoff is still a prominent figure in the public eye

Andrew Flintoff is still a prominent figure in the public eye

It’s possible that Stokes may yet reach that exalted level one day, perhaps if he wins next summer’s Ashes all on his own. But it’s very much odds against: the inevitable fracturing of the attention market in the personalised internet age means cricket has never been easier to find or easier to avoid, its stars both more visible and less seen than ever. Stokes’ gargantuan feats with bat and ball, hands and mouth, remain destined for a niche audience.

And so there you have it: Grace, one of the most famous men in Victorian Britain; Botham, the most famous British sportsman of the colour television age; Flintoff, the most famous cricketer of his generation; Stokes, “the ginger one” who failed to get admitted into a nightclub. As a line plot of English cricket’s trajectory over the last 150 years, it’s as good a measure as any.