In the latest issue of Wisden Cricket Monthly, a 22-strong panel of writers and broadcasters from across the world picked Steve Smith in their Test team of the year. Here, Adam Collins and Geoff Lemon justify the former Australia captain’s selection but argue he’s missed a valuable opportunity to broaden his horizons during his ban.

This article originally appeared in issue 15 of Wisden Cricket Monthly. Click here to subscribe to the magazine

A lot of people will blink hard at seeing Steve Smith’s name in this team. It’s the Test team of the year, is it not? And didn’t he spend most of that year suspended by his own board from all international cricket, and the bit beforehand being worked over by South Africa’s bowlers?

Well, yes. But the qualification period isn’t 2018, it’s from November 2017. Meaning it captures the most recent Ashes entirely, in which Smith made three centuries and a couple of near-centuries, in a Bradman glut of 687 runs at 137.4. He guaranteed his team the tiny trophy off his own bat, which in turn guarantees him a spot in this imaginary team. It starkly illustrates how far and fast he fell, after his teammates were caught sandpapering a cricket ball with his knowledge.

His process of public rehabilitation began days later during his tearful press conference at Sydney Airport. Mercifully, this process wasn’t set back by a recent bid from the players’ union to have Smith’s ban reduced. While the case was theoretically sound, it was never going to work for his public reputation. Australians will welcome their wunderkind back with open arms in March 2019, but only after doing his time. There are no shortcuts.

Smith and his former deputy David Warner have been playing grade cricket while they serve their bans

Smith and his former deputy David Warner have been playing grade cricket while they serve their bans

So where has the ban left him? The financial toll on Smith has been estimated at $7million AUD considering all of his playing and commercial contracts. To that end, and to keep his game in working order, it was understandable that he wanted to fill his gap year by working. But at what cost?

In truth, it makes for a fairly sad list. After the broken shell of Smith left Sydney Airport, he signed up to play in a T20 circus in Toronto. En route, he was papped by a scumbag media organisation having a beer alone in a New York bar, as though this was some personal failing. He went to T20 leagues in the Caribbean and Bangladesh, with some Sydney grade games in between. All cricket, all the time.

There is still a chance that Smith will captain Australia again after his two-year suspension from leadership. Perhaps not immediately but eventually. His year away from the international frying pan could have been used as an investment in his future self by colouring in the gaps that have been missed over the last decade as he systematically went about developing his game.

Take Jobe Watson, former captain of the Australian Rules football club Essendon. In a case of players’ trust being breached by those around them at a club with a dismal culture – sound familiar? – most of the playing list was banned for a year for drug code violations.

Watson, the captain, took off for New York City. But not for a holiday. He went to work in a café, embracing the anonymity of his new surrounds. He returned to Australia with a better handle on the world around him and became a better leader as a result. There weren’t many better examples for Smith than that.

A substantial factor in the demise of Smith’s team was the fact that the captain was appointed young and green, with no life experience outside of the world he’d entered as a teenager. He had few outside interests and showed no sign of a strong identity of his own. So when stronger personalities asserted themselves, he either aped them or went along.

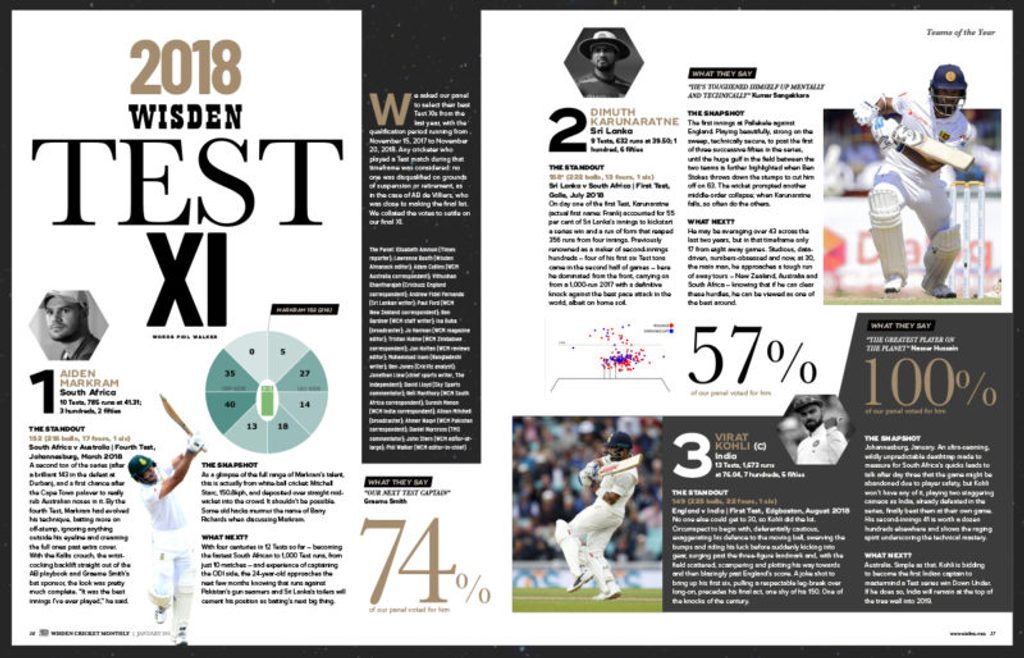

The Test team of the year revealed in Wisden Cricket Monthly

The Test team of the year revealed in Wisden Cricket Monthly

In a parallel universe, picture how Smith could have spent a year finding some of the breadth that his lifestyle had never allowed. With the contacts and cash to dissolve any barrier, he might have travelled to countries where nobody has heard of cricket, let alone heard of him. He might have volunteered to build houses in Brazil, or moved to an Aegean island to learn Greek. Hiked the Appalachian trail or assisted on an archaeological dig. Imagine Steve Smith training to be a yogi like Cameron Bancroft, or working on a fishing boat. Going on a road trip during which he could form an unlikely friendship with a humorously incompatible character, in the process discovering both America and himself. Realising that the real Test centuries were the friends he made along the way.

Instead, he kept doing what he always did. He batted. Not for ego and probably not for cash but precisely because it is all he has ever known. He let a world of opportunity slip by for the comfort of a familiar orbit.

So when he does return in Australian colours, the question isn’t just about whether he can newly attain his batting dominance of old, or whether he’ll be picked or accepted again as a leader. It’s whether he’s able to deliver as a leader. It’s whether he’s coming back a broader or better person, with anything significant learned from the experience.