Jonathan Liew says Dinesh Karthik’s stunning, match-winning innings in last month’s Nidahas Trophy final was an indicator of where modern batting is heading.

Jonathan Liew writes every month in Wisden Cricket Monthly

MORE BY JONATHAN LIEW

It’s the 19th over of the Nidahas Trophy final in Colombo. India need 34 off 12 balls to beat Bangladesh. Dinesh Karthik is about to face his first delivery from Rubel Hossain. It’s full, fast and just outside off. Karthik takes a big stride down the pitch, turning it into a full toss and clouting it over long-on for six.

The second ball is full, fast and just outside off. Karthik stays where he is, and smears it over mid-wicket for four.

The third ball is full, fast and just outside off. This time Karthik takes a big step back in his crease, almost treading on his own stumps, and swings it high over square-leg for six.

Karthik’s brilliance led India to a dramatic victory

Karthik’s brilliance led India to a dramatic victory

The last ball of the over is full, fast and just outside off. This time Karthik does not so much play the ball as enact an entire dance routine with it: feinting with his right boot as if to back away to leg, then running all the way over to the off-side and flipping the ball over fine-leg for four.

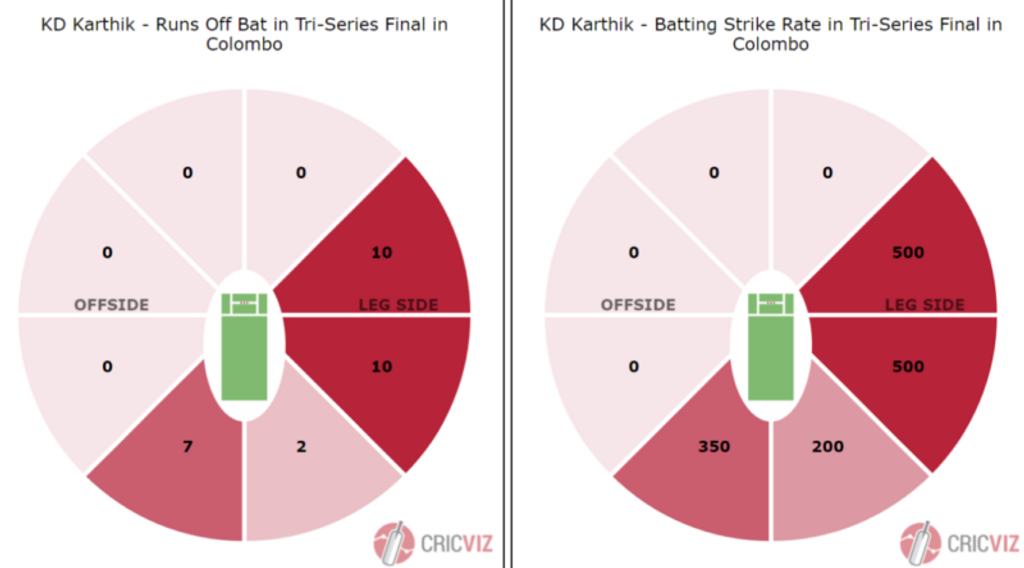

Four almost identical deliveries, addressed in four different ways, and despatched to four different areas of the ground. Of course, Karthik’s last-ball six to win the game ended up stealing the headlines. But it was that penultimate over – almost flawless, and yet carted for 22 – that, in its own strange way, showed us exactly where modern batting is heading.

When we talk about variations in cricket, we’re almost always referring to bowlers: yorkers and cutters, arm balls and slower balls, doosras and googlies. But these days, nourished by the anarchy of Twenty20 and its thirst for new frontiers and cutting edges, a new phenomenon is beginning to crystallise. Now, it’s the batsmen who come with variations of their own.

A new phenomenon is beginning to crystallise. Now, it’s the batsmen who come with variations of their own

Around this time last year, Sunrisers Hyderabad’s Deepak Hooda played a shot that reduced the IPL’s commentators to incredulous laughter: not only shuffling across his stumps, but behind them, striking the ball from behind the bowling crease. And in the audacity of Hooda and Karthik and many others, we are watching the geography of batting being transmuted before our eyes into something boundless, lawless, almost shapeless.Of course, batsmen have always made creative use of their space, whether sauntering down the pitch to the spinner, or stepping across their stumps to turn straight balls to leg. More recently, the last decade has seen perhaps the greatest era of disruptive shot innovation – the switch-hit, the ramp, the lap sweep – since the early 20th century.

Kevin Pietersen playing a switch hit in a Test match against India

Kevin Pietersen playing a switch hit in a Test match against India

But somehow, this feels new, different, transgressive. Fifteen years into T20, it seems batsmen are finally beginning to challenge one of cricket’s longest-held orthodoxies: that good batting comes from repetition and rhythm, grooving and honing your responses until they become second nature. Now the best short-form batsmen – Chris Gayle, Virat Kohli, AB de Villiers – talk of having three possible shots to every ball. Brendon McCullum can launch a length delivery over backward point, over backward square-leg, dead straight, and virtually everywhere in between, and as the ball leaves the bowler’s hand it’s possible even he doesn’t know which one he’ll plump for.

We are watching the geography of batting being transmuted before our eyes into something boundless, lawless, almost shapeless

This isn’t just unorthodoxy. It’s wilful shapeshifting, masks upon masks, pre-emptive elusiveness, alchemy on the fly. The net result is to upset or even invert the one built-in advantage that bowlers have enjoyed since the dawn of time: that they know what they’re going to bowl, and the batsman doesn’t.And as ever, it’s the bowlers playing catch-up. Detecting subtle variations in stance from 40-50 yards away is no mean feat, and even if you see a batsman on the move, adjusting in full flow is no easy task. “If they move to the leg-side, sometimes you want to push it wide,” explains Tymal Mills. “But as soon as you’re in your jump, gather, delivery stride, the human eye tends to follow a moving target. Unless you’re aiming away from them in the first place, it’s easier said than done.”

Nor is this purely a short-form phenomenon. Part of Steve Smith’s devastating potency during the Ashes was his ability to mock England’s bowling plans by playing different shots to the same delivery: often to different sides of the ground, sometimes even with different stances, different backlifts. In the rapidly shifting field of batting variation, Smith has been an indisputable pioneer. One of the more oblique reasons to lament his recent troubles is that by the time he returns, he may be no longer.