Former England batsman Michael Carberry tells Jo Harman the national selectors have continued to show “utter disrespect” for the specialist role of the opener.

To read ‘Confessions of an England opener’, as Michael Carberry, Sam Robson and Adam Lyth reflect on the technical and mental challenges of the most difficult job in cricket, pick up a copy of the October issue of Wisden Cricket Monthly

If further evidence was needed that being a Test opener in England is the toughest gig in international cricket, then this summer’s Ashes provided it. Faced with exceptional pace attacks and seamer-friendly conditions, England’s average opening stand for the series was 16.6. Australia’s was just 8.5.

David Warner, with 21 Test hundreds in his back pocket, was reduced to a state of paralysis. “I don’t think David solved the puzzle,” said Australia coach Justin Langer. “He’ll probably be very relieved when he gets on the Qantas flight and doesn’t have to face Stuart Broad for a while I reckon.”

Out of the debris rose Rory Burns. His average of 39 won’t look like much when scorecards are revisited in years to come but it was a Herculean effort from the Surrey left-hander when you consider a) his form ahead of the series and b) the track record of English openers over the past seven years.

Burns scored 390 runs in the 2019 Ashes, including one century and two half-centuries

Burns scored 390 runs in the 2019 Ashes, including one century and two half-centuries

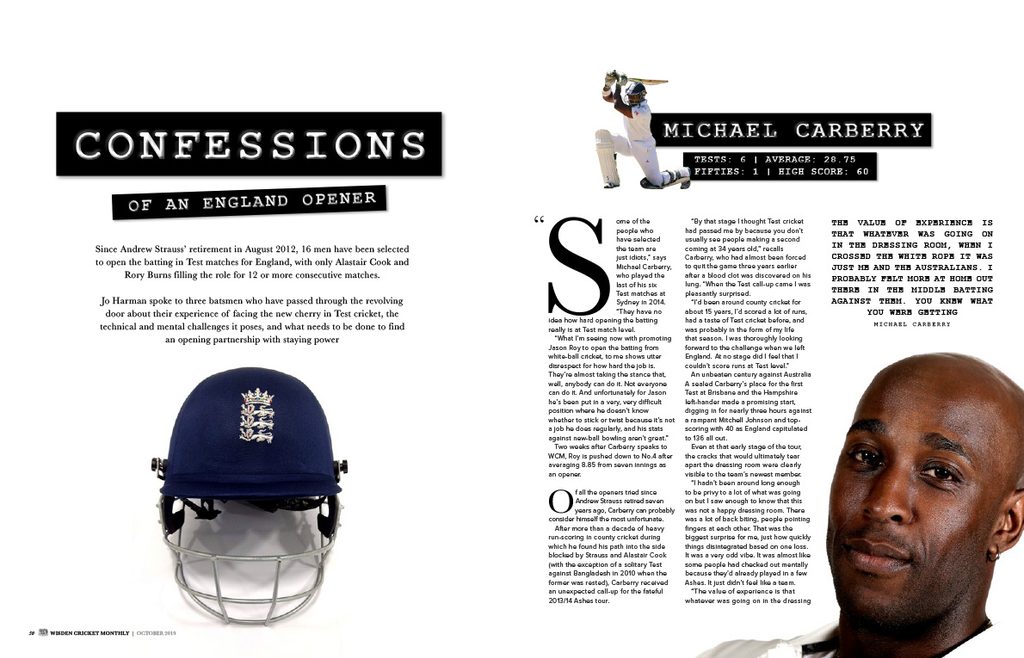

Since Andrew Strauss’ retirement in August 2012, 16 men have been selected to open the batting in Test matches for England, with only Alastair Cook and Burns filling the role for 12 or more consecutive matches.

The difficulty of the job in part explains the not-so-merry-go-round of opening batsmen, but Michael Carberry, who played the last of his six Test matches at Sydney in 2014, believes there’s another reason.

“Some of the people who have selected the team are just idiots,” says the former opener in the October issue of Wisden Cricket Monthly. “They have no idea how hard opening the batting really is at Test-match level.

Read the full interview in issue 24 of Wisden Cricket Monthly

Read the full interview in issue 24 of Wisden Cricket Monthly

“What I’m seeing with promoting Jason Roy to open the batting from white-ball cricket, to me shows utter disrespect for how hard the job is. They’re almost taking the stance that, well, anybody can do it. Not everyone can do it. And unfortunately for Jason, he’s been put in a very, very difficult position where he doesn’t know whether to stick or twist because it’s not a job he does regularly, and his stats against new-ball bowling aren’t great.”

Two weeks after Carberry speaks to WCM, Roy is pushed down to No.4 after averaging 8.85 from seven innings as an opener before being dropped from the side altogether.

Roy struggled to take his white-ball heroics from World Cup 2019 into the Ashes

Roy struggled to take his white-ball heroics from World Cup 2019 into the Ashes

Of all the opening batsmen tried since Strauss retired, Carberry can probably consider himself the most unfortunate – a player who had waited so long for his opportunity receiving it at, in hindsight at least, the most inopportune time.

After more than a decade of heavy run-scoring in county cricket, during which he found his path into the side blocked by Strauss and Cook (with the exception of a solitary Test against Bangladesh in 2010 when the former was rested), Carberry received an unexpected call-up for the fateful 2013/14 Ashes tour.

“I’d been around county cricket for about 15 years, I’d scored a lot of runs, had a taste of Test cricket before, and was probably in the form of my life that season,” he recalls. “I was thoroughly looking forward to the challenge when we left England. At no stage in my mind did I feel that I couldn’t score runs at Test level.”

An unbeaten century against Australia A sealed Carberry’s place for the first Test at Brisbane and he made a promising start, digging in for nearly three hours against a rampant Mitchell Johnson and top-scoring with 40 as England capitulated for 136 all out.

Even at that early stage of the tour, the cracks that would ultimately tear apart the dressing room were clearly visible to the team’s newest member.

“I hadn’t been around long enough to be privy to a lot of what was going on but I saw enough to know that this was not a happy dressing room. There was a lot of backbiting, people pointing fingers at each other. That was the biggest surprise for me, just how quickly things disintegrated based on one loss.

“The value of experience is that whatever was going on in the dressing room, or whatever was being said behind people’s backs, when I crossed the white rope it was just me and the Australians. To be honest, I probably felt more at home out there in the middle batting against them. You knew what you were getting.”

Carberry scored 13,868 first-class runs in his career, but played just six Tests

Carberry scored 13,868 first-class runs in his career, but played just six Tests

Despite not nailing a big score, Carberry continued to handle the relentless ferocity of Johnson and Ryan Harris better than any of his teammates, scoring a maiden half-century in a thrashing at Adelaide and a couple of gutsy 40s and 30s elsewhere. Facing the new nut against the quickest bowler in the world, he emerged from one of the most humiliating and destructive series in English cricketing history with 281 runs at 28.10. Of his teammates, only Kevin Pietersen scored more, but neither was selected for the first Test against Sri Lanka the next summer.

“I don’t feel a bit unfortunate, I was unfortunate,” says Carberry. “That’s the system we’re in. If your face fits you’re going to get opportunities. There were a lot of times when Alastair Cook and Andrew Strauss weren’t necessarily always making runs but the system stuck with them. That’s different to what happened to me. I got a couple of Test matches, in relative terms had an OK tour, and yet was jettisoned.

“Eventually the selectors came out of the woodwork to tell me why I wasn’t selected and it was because they were looking in a younger direction. I think my response was, ‘If you pick me just after my 34th birthday to go on an Ashes tour, I can’t really see how I’ve dramatically aged in three months’. The reason for me kind of washed off. I knew there were a lot more underlying reasons as to why I wasn’t picked.”

Carberry’s comments during the tumultuous Ashes fallout in which he defended the conduct of the ousted Pietersen and highlighted the “very, very strange decisions” made by the ECB would not have counted in his favour. But he has no regrets about speaking frankly.

“If a player’s got a deficiency, as we all do, why the hands-off approach?”

“If a player’s got a deficiency, as we all do, why the hands-off approach?”

He returned to county cricket and scored 2,122 first-class runs across the next two seasons. Meanwhile, the revolving door continued at pace, with Cook accompanied to the crease by 11 different opening partners between June 2014 and the end of 2016.

Carberry accepts the County Championship schedule doesn’t create the ideal breeding ground for Test-ready openers – “You’re asking young players to go out in the middle of March to bat on puddings and prepare for Test level” – but says that once the selectors have identified their preferred candidates, it’s essential they show them patience. Otherwise, the problem is only going to get worse.

“You need to invest in good openers. You have to give people a chance. As openers, we don’t have the luxury of being able to come in against the old ball where it’s doing less. You see it on the first morning of a match. Everyone’s prodding the wicket. ‘Oh yeah, this looks a belter’. It’s never a belter when you’re facing the new ball. If the ball is going to do something, generally you’re the one who’s going to get it.

“If a player’s got a deficiency, as we all do, why the hands-off approach? Actually get in there and coach them, guide them. That’s what coaches are there for, surely? Not just, ‘He hasn’t scored runs in five Test matches, let’s throw him in the bin’.

“I’m telling you now, the youngsters who are coming through the game, not many of them want to open. And, honestly, I don’t blame them. There’s a massive fear. I coach kids now. If you’re seeing guys at the top of the game getting dropped after three, four or five games, and yet the middle order seem to be getting a longer run where it’s supposedly easier, why would you want to open the batting as a youngster?”