Shannon Gill remembers the mighty West Indies shredding his view of Australian superiority in 1988/89, only for his heroes – inspired by mustachioed Merv – to come out the other side stronger than ever.

First published in 2017

First published in 2017

If you were an Australian child of the 1980s you thought anything was possible. In your limited view of the world Australia played a starring role.

We could win the America’s Cup. We could make Crocodile Dundee. INXS, Men at Work and others made dents on US charts. Pat Cash was scaling grandstands at Wimbledon. A before-the-choke-became-a-joke Greg Norman swaggered around golf courses. Our girl Elle was on the cover of Sports Illustrated. Millionaire tycoons in white shoes were throwing cash around – before they crashed and fled to Spain (see Christopher Skase) – and in Bob Hawke we had a prime minster we all liked who could down a yard-glass. All the while we did it with a Mick Dundee “That’s not a knife…” insouciant charm. Hell, Paul Hogan even co-hosted the Oscars.

By 1988’s Bicentenary celebration year the fervour and pride went into overdrive, as flags and boxing kangaroos covered the nation and kids were taught a questionable and whitewashed version of Australian history. It all added up to a kid thinking that Australia was impervious to anything the world threw at it. Then the West Indies showed up.

Cricket was wallpaper for me up until 1988/89 when the sport came alive. A combination of a cricket bat appearing during lunchtime at school and Scanlens Cricket Cards on shop counters set the scene, and when the Windies arrived the world shook for me.

When confronted by the West Indies, the cocky, upstart, laugh-in-the-face of danger Australia that I thought I knew suddenly had all the poise and assuredness of the pimply, voice-still-breaking teenager on his first shift at the checkout counter.

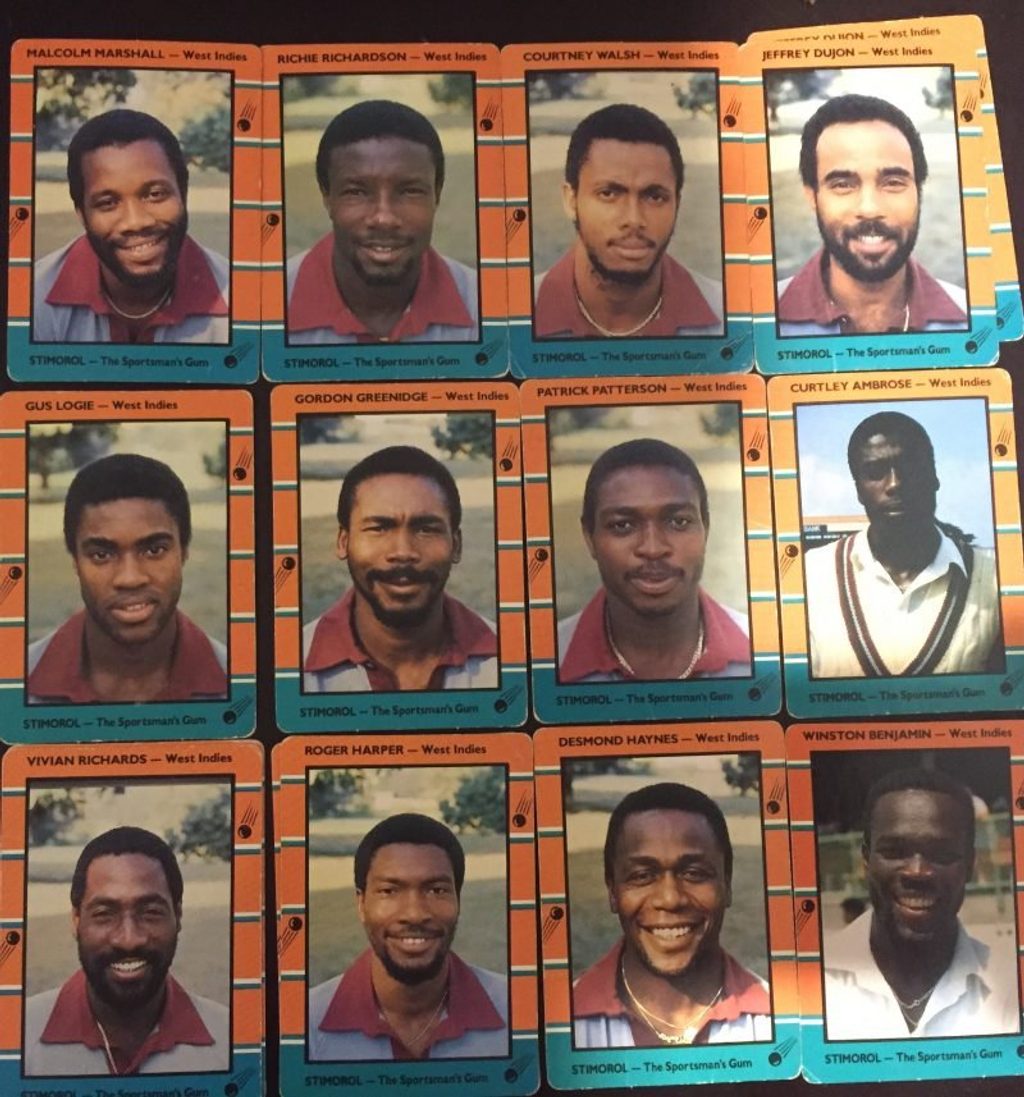

The 1980s West Indies were gods and they looked mighty cool on those cricket cards – still the best sporting cards ever made, the cheesiness of the captions a highlight. And as the 1988/89 summer rolled around they had a new weapon on board: Curtly Ambrose.

Scanlens Cricket Cards profiled the touring West Indies

Scanlens Cricket Cards profiled the touring West Indies

Impossibly tall and impossibly good, if Michael Holding was whispering death, Curtly was bounding horror and he captured my imagination more than anyone else with a mix of fear and admiration. The limbs were so loose; each stride to the wicket seemed to cover 10 metres, his boots on the cricket cards looked as tall as the stumps.

The Windies blew through Australia in the first two Tests, but the Sunday afternoon of the second match of the series at Perth also lit the fire. A 200-run partnership between Graeme Wood and Steve Waugh gave the hosts hope. But even then, compared to superheroes Curtly, Viv and Richie, Wood and Waugh looked like blokes you saw down the street.

Later Curtly graduated to villain when he floored Geoff Lawson, a broken jaw and a stretcher required. Watching TV at the kitchen table there was something electric as Australia promptly declared and Merv Hughes ran in hard for a few overs before stumps. When he got Gordon Greenidge lbw first ball not only was it a hat-trick (he’d cleaned up West Indies’ first innings with consecutive deliveries) and not only was the reaction the most exhilarating thing I’d watched on television to that time, but we now had a guy who looked just as scary as the bad guys and didn’t give a f*** what anyone thought. Finally Mick Dundee had shown up, albeit with a handlebar moustache.

Merv heroically took 13 wickets in that losing cause and in the process breathed life into the summer. The one-dayers came with the debut of the glorious ‘baseball’ World Series Cup uniforms and day/night cricket that had us all talking at school, and Merv had transformed from a state cricketer with a slightly ridiculous moustache into a national hero. There was his tongue in AB’s ear, the ‘Merv 4 PM’ crowd signs, the crowds mimicking his warm-up routines – all things that made an impact on a seven-year-old. Merv vs Curtly suddenly now looked like a fairer fight. As 1988 became 1989, Merv was only rivalled by Yahoo Serious for ubiquity (for English readers, Serious was the star of Young Einstein, an Aussie film that was a box-office sensation down under but rubbished everywhere else).

Despite all that, Australia couldn’t win a game against the West Indies. Sure, we beat Pakistan in some one-dayers, but the Windies figuratively and literally beat up on Australia at the MCG Test as if the Merv uprising gave another motivation to keep the natural order. Reading The Sun after Boxing Day I scanned through the injuries and for the first time I saw the word ‘scrotum’ in print in reference to Ian Healy’s painful blows – he was one of about six players that were battered.

The damn wall finally broke on January 5 in an ODI when, after what seemed like months, Australia finally beat the Windies in a game of cricket. Steve Waugh took a ridiculous running catch while swerving the sightscreen to dismiss Roger Harper and all of a sudden there was pride. The Merv exercise routine went to new levels of bizarre.

I had to know more. I found a copy of Australian Cricket magazine at the newsagents with Waugh on the front and it became a constant companion for months, reading it from back to front and discovering the back-story to what was going on out there.

Going toe-to-toe with the West Indies captured the imagination of the Aussie public

Going toe-to-toe with the West Indies captured the imagination of the Aussie public

Momentum was gathering as Australia beat West Indies in consecutives one-dayers – punctuated by a tense first World Series Cup final victory that I listened to in bed while biting my nails. I was heartbroken when the series was lost due to some unfair rain rules.

There was the feeling of living through the struggle and almost triumphing that I was relating to. The switch back to five-day cricket sealed the love affair, as Allan Border somehow took 11 wickets at the SCG and we had ourselves a Test win. The tour finished with a draw at Adelaide but the previously anaemic Australians now looked strong and confident and had begun to boss the world bosses. Dean Jones, who couldn’t make a run in November and December, hit a double-century and Merv swatted a six from the last ball of a session to bring up his fifty. Off the back of the 1988 Olympics I’d taken up athletics on a Saturday morning but I rushed home that day to watch Merv and Deano. Athletics was gone – summer was cricket now.

This was a rebirth of Australian cricket that was consummated by the 1989 Ashes win that followed. Australia would only lose one home series for another 20 years. Sport is most fun when the underdog rises, and it was the summer of struggle in 1988/89 that made the lasting impact.