England’s historic Hedley Verity-inspired victory was just the start of the amazing sporting pageant that lit up the summer of 1934, writes Robert Winder.

First published in 2015

First published in 2015

When Graeme Swann sealed a rare (bowling Mitchell Johnson) the celebration was given extra warmth by the fact that this was the first English victory in this famous fixture for over 70 years. But flicking back to that grand day in 1934, when Australia were toppled by the left-arm spin of Yorkshire’s Hedley Verity, I was surprised to learn that this was not merely the last time England had beaten Australia at Lord’s: it was the only time they won there in the entire 20th century. And it was the high point of an unusually tense summer, since this was the rematch following the furious winter of 1932/33, when Douglas Jardine’s England had battered Bradman and company in Adelaide and Sydney, using Harold Larwood’s electrifying bowling as the spearhead of a bad-tempered new gambit: Bodyline.

So the atmosphere at Lord’s, that grey weekend, was rapt with expectation.

England batted first and scored 440, and when Verity dismissed the Don in the first innings (caught and bowled, following a strangely hesitant swish) the billboards read simply: “He’s out!” Bradman was a nonpareil, so everyone knew what that meant.

Australia finished the second day on 192-2, leaving the game well-balanced. But overnight rain gave the next day’s pitch a dark green tinge, and when Verity looked out of his hotel window he could see gleams of water streaking silver on the road.

“I shouldn’t wonder if we don’t have a bit of fun today,” he murmured.

When he came on to bowl a few hours later, drifting to the wicket in that famously unhurried way of his – “lightly and decisively”, as his captain put it – the game at once took on a fresh complexion. As always, Verity found “an impeccable length” right away, but the ball was turning and lifting too. In the slips, Walter Hammond was smiling. “We knew,” he said later, “that the Lord had delivered them into our hands.”

It didn’t take long. Out they marched, the baggy green caps, and back they traipsed. As Herbert Sutcliffe put it: “When the rain had done his work, Verity was able to do his work, and that was the end of it.” He took 6-37 in a flash, and when Australia followed on he was at it again, plucking their feathers like a fox in a chicken coop.

As always, the key wicket was Bradman’s. From the word go he seemed fidgety, and when Verity floated one at his leg stump he leapt at it, dropped his shoulder like a novice and had a swing. The ball flashed high into the murky Lord’s air until Ames trotted forward and took the catch. Australia’s chief and legendary hope was gone.

Crowds queueing up for the Lord’s Test, 1934

Crowds queueing up for the Lord’s Test, 1934

In Bowes’ view it was “one of the worst shots he ever played”; Wyatt judged it born of “desperation”. Either way, the heart seemed to go out of Australia in a rush. They came, they took guard, and back they went. The last wicket fell at 10 to six, meaning that Verity had bowled virtually unchanged for over five hours, taking 14 wickets in a single day – bettering his merely useful 7-61 in the first innings with a superlative 8-43 in the second. After tea, he snagged six for just 15 runs.

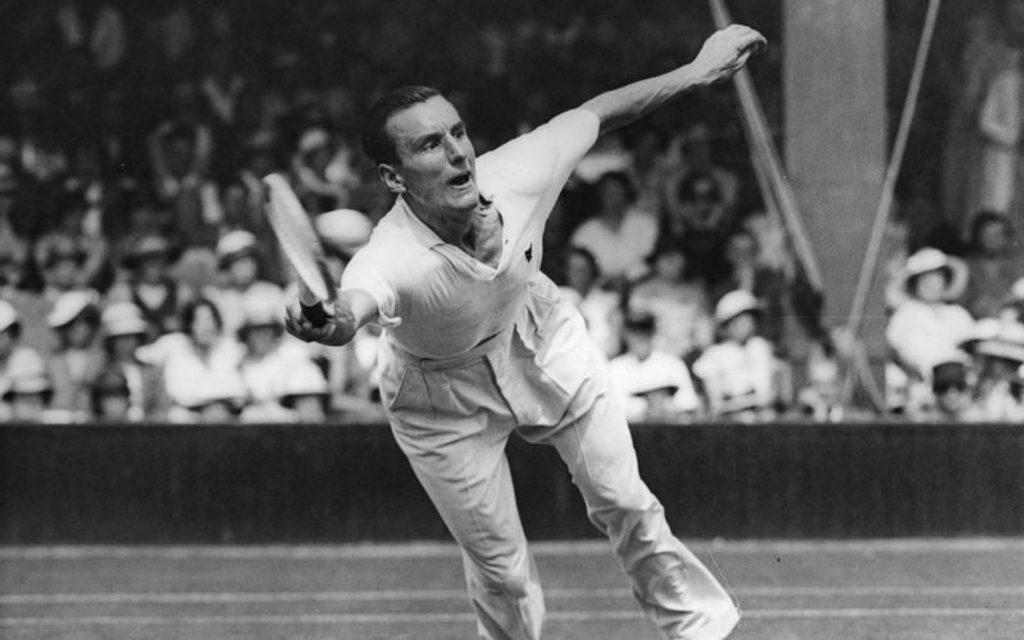

Verity’s stunning effort was only the start of the amazing sporting pageant that lit up the summer of 1934. On the same day he polished off the Australians, Henry Cotton was setting out on what would prove to be a record-breaking tilt for the Claret Jug at Royal St George’s in Kent (the historic 65 he shot in the first round actually inspired Dunlop to name a golf ball after it). And a week or so later, a coming thing named Frederick Perry was warming up for the first of his three Wimbledon victories.

There had not been a home champion in either of these great events for years (Arthur Gore was the last English winner of Wimbledon in 1909, and Jim Barnes’ Open win in 1925 was only a memory) just as there had been no victory over Australia at Lord’s since 1896. Thanks to the supremacy of American golfers and French tennis stars, the prospect of a domestic triumph in any of these fields seemed remote. But that is what happened in this midsummer rush of 1934. The Lord’s Test, the Open, Wimbledon – the three crowning glories of English sport all fell in a single wonderful swoop. It was, to use an overworked term, a shining annus mirabilis for English ball games.

Fred Perry’s first Wimbledon singles title capped a remarkable English summer

Fred Perry’s first Wimbledon singles title capped a remarkable English summer

There were black clouds behind these silver linings, however. Something profound had perished in the bloody mud of Flanders. No one could forget the way the papers described the lethal first day of the Somme, when 30,000 young men were massacred in just one hour after being ordered to walk – on no account run; vital to keep in formation – into the hot spray of machine gun fire. And then came the General Strike and the Wall Street crash; and the pound was shaken loose from its moorings. Mass unemployment stalked the land, and it was hard to be optimistic about anything.

In 1934, Britain was only just beginning to emerge, dazed and blinking, from all this. Out in the wider world, meanwhile, the silhouettes of new demons – Hitler, Stalin, Mao, Imperial Japan – were darkening the sky. It began to dawn on people that it might be only half-time in the struggle with Germany. The papers were heavy with martial images: naval exercises in Scapa Flow, icy waves crashing over grey decks and forward guns; submarines on the slipway in Barrow-in-Furness; HMS Malaya blasting its guns off Spithead, HMS Sussex and HMS Revenge tooting past Gibraltar.

In the House of Commons the chancellor of the exchequer, Neville Chamberlain, didn’t talk about the “long-term economic plan”, but turned to Dickens to support his point that the skies were clearing: “We have finished the story of Bleak House,” he said, “and are sitting down to enjoy the first chapter of Great Expectations.” It would be silly to suggest that the sporting glories that followed this remark were an actual response to this shift in the national mood, but they certainly came at an opportune time. They suggested that perhaps, maybe, England could start enjoying life again.

England would not again beat Australia at Lord’s until 2009

England would not again beat Australia at Lord’s until 2009

Not surprisingly, the simple fun of sport was extremely appealing at a time like this. As the Telegraph put it, revelling in the “triumph heaping on triumph… success in golf, in tennis, in the cricket field”, it was a sign of “recovered national confidence.” The New York Times made the same point: “It’s about time they declared a Bank Holiday over there,” it noted, “to celebrate the comeback of Great Britain in sports.”

Less than a decade after his historic effort at Lord’s, Hedley Verity was hit in the chest by a storm of German bullets as he urged his platoon forward during the 1943 Allied invasion of Sicily. But nothing could erase or dim the memory of the magical afternoon in which he had bewildered and vanquished the mighty Australians. As Neville Cardus, never slow to reach for the most lyrical of moods, put it: “The Gods of the game, who sit up aloft and watch, will remember the loveliness of it all, the style, the poise on light toes, the swing of the arm from noon to evening.”

It is possible that in time we will remember Graeme Swann in that sort of way. But then again, maybe not.