With cricket increasingly encouraging new thinking and challenging old orthodoxies, what does this mean for the future of coaching? Jon Hotten meets three ‘mavericks’ whose philosophies and methods are starting to change the way our game is coached and understood.

Life comes at you fast, as they say in the movies. This piece began as a story about three ‘maverick’ coaches, interesting people working in unorthodox ways in that nebulous nether-zone ‘outside of the system’. It was going to ask rather grand, fundamental questions about the way the game is played and taught. After all, there’s something seductive about the notion that Everything We Know Is Wrong.

A book that began a kind of quiet revolution, Michael Lewis’ Moneyball, worked on just such a principle, and that book has had its effect on cricket: one of its early readers was Andy Flower, who was running the ECB’s National Cricket Performance Centre at Loughborough. Moneyball was published in 2003, the same year that T20 cricket began, and hard statistical analysis fitted well with the new game that was emerging. Cricket was to be demystified by numbers, undressed in a way that it had never been before, revealing gleaming ‘pathways’ along which the players of the future would walk. It would become measurable, empirical, identifiable.

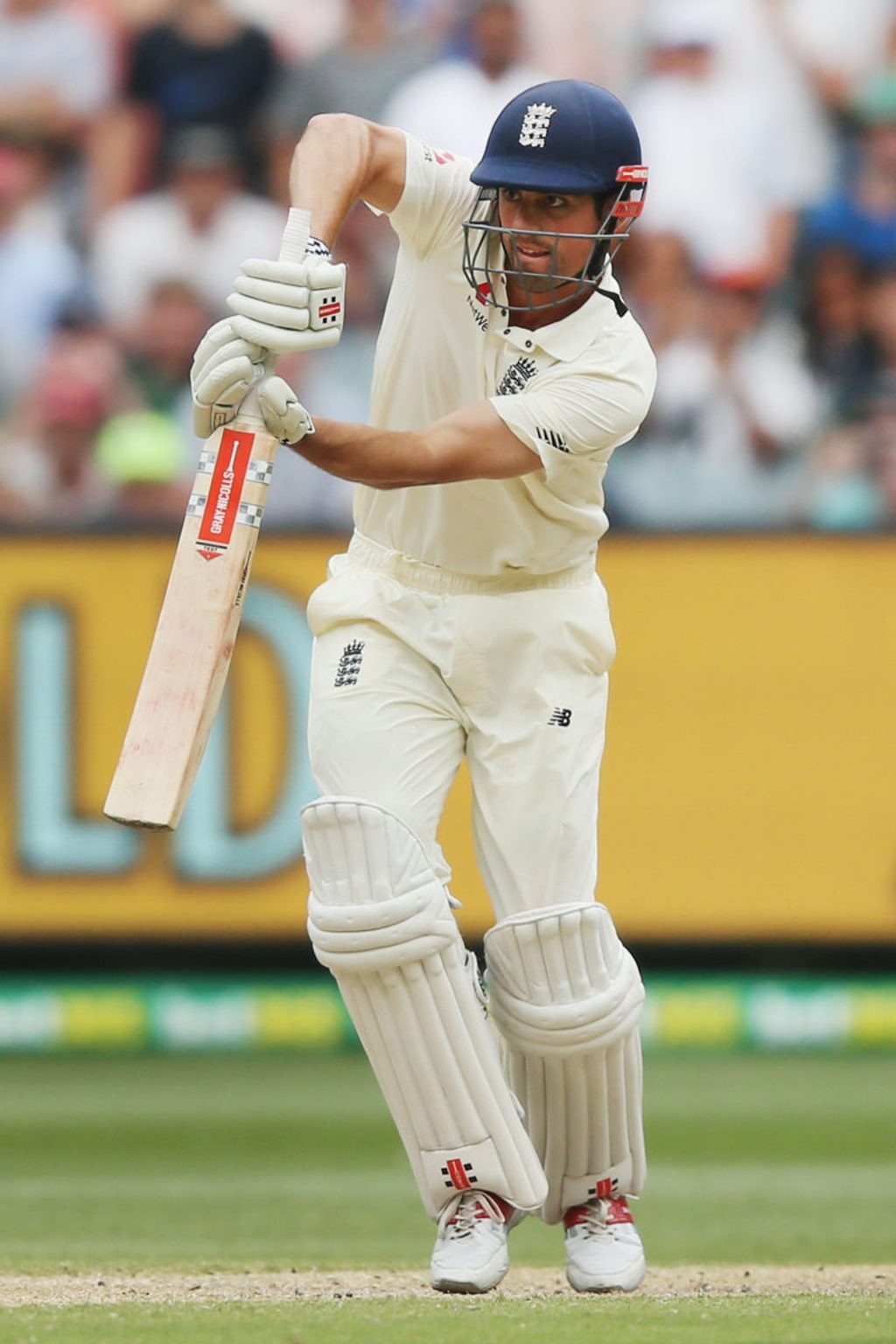

Alastair Cook has regularly tweaked his technique throughout his career

Alastair Cook has regularly tweaked his technique throughout his career

At the same time, T20 cricket ushered in the greatest changes to established technique since the young Grace grew his beard out and began playing forward and back, assaulting the bowlers of Victorian England in ways that no one had before. Watching him play, Fuller Pilch, who was regarded as the game’s premier batsman until Grace’s emergence, had exclaimed: “Why this man scores continuously from balls that old Fuller would have been thankful to stop.” Fuller’s words could easily have crossed the centuries, as pertinent to Chris Gayle’s 66-ball 175 not out in the 2013 IPL as it was to Grace’s 224 not out at The Oval in 1866.

From all of this, a paradigm was formed. The modern England cricketer, chosen early, walked his pathway and emerged blinking into a life of development squads and Lions tours, central contracts and NOCs, a new, shimmering world in which everything that could be controlled was controlled, from the timing of their trigger movements to the correct quinoa portion size. Loughborough was a vision that for so long during the fractured 1990s seemed chimeric and distant, yet that had somehow become real.

It existed to make cricketers: batsmen, fast bowlers, spinners. It was the gravitational centre of England’s methods, and as such it established a new orthodoxy. And it meant that, in having all of English cricket within it, there were people left outside of it too, people whose ideas on the game didn’t quite fit.

***

The Batting Lab is situated on a former tennis court in the back corner of some light industrial units on a farm in rural Oxfordshire. There are some rather lovely stone buildings that have been converted into offices, a bustling café, and then a car park and a portakabin that serves as a kit store-cum-shelter for the disciples that travel here.

The man they come to see is Gary Palmer, a 51-year-old former pro cricketer who had 10 years with Somerset as an all-rounder, but who was perhaps better known as the son of the much-loved umpire Ken. Five years ago, he did a deal with the farmer over the tennis court, re-fenced and re-covered it and opened for business. As laboratories go, it’s more local middle school than Large Hadron Collider, but as word about the work that Palmer did spread through the game, international batsmen began making the journey to hear what he had to say about their craft.

Palmer demonstrates his front-on batting method

Palmer demonstrates his front-on batting method

While Palmer is necessarily guarded about exactly who he has worked with, Ian Bell, Nick Compton and Charlotte Edwards are among the names that appear on his website. In April 2015, he began working with Alastair Cook, a relationship that Cook has described as “in one way like a golfer has with a swing coach… purely just technical”. England’s all-time leading run-scorer would often drive from his home in Bedfordshire out to Oxfordshire in the early mornings to take guard before the doleful, unblinking eye of Palmer’s trusty bowling machine.

After we’ve sat in the café to discuss his philosophy, Palmer gives me a coaching session, one that begins at 1pm and, as time blurs, concludes three hours later in a revelatory fervour. Cook’s golf swing analogy stands. What Palmer has done is to strip down batting, from stance and grip to follow-through, and examine each of its component parts, before rebuilding them into something subtly and yet radically unlike anything else. Like a swing coach, he adapts what he knows to the make-up of the player he is working with. In my case, as a club hacker, that means interrogating everything I thought was certain about my game.

Alastair Cook with his technical coach, Gary Palmer

Alastair Cook with his technical coach, Gary Palmer

Without trying to clumsily explain in a paragraph what Palmer has taken a lifetime to learn, he uses four angles of delivery – left-arm over in-swing and away-swing, right-arm over the same – and makes you hit the ball back past the bowling machine.

The stance is opened, the leading shoulder turned outwards. Hands are held high and close to the body, feet are pointed directly down the pitch. In a theme that will reoccur, the backlift in this position points almost towards gully. At first it is drastically uncomfortable, but that feeling soon eases. So attuned is Palmer’s eye that he will sometimes look at how I’m standing before the ball is delivered, a position to me that feels no different to the ball before or the one after, and say, “This will be a good shot…” He is always right.

“I could have probably used some help on the psychological side,” Palmer says when he reflects on his playing career. “Everyone thought I was going to play for England because I smashed 78 in my second game, but I realised how difficult it was…”

His desire was so fierce that it became stifling and counter-productive, yet it also lit his hunger to understand, at the deepest level, what batting was. Arriving at Somerset while Viv Richards was still at the club was formative. “From a young age, Viv must have worked out, ‘This is the best way of doing it’. Whether that’s luck or his environment, I don’t know. But as a coach, if you can take what he found out then, and implant that in a young player, you can give them clarity.

“If you’ve stumbled upon a flawed technique, yet you’ve got a good eye and good concentration, you can get by and become a county player, and that’s great, but it’s so powerful to get the right technique at a young age. That’s what I do even with 10-year olds – slightly more open, point your laces, pick your bat up here. As far as basics go, they’re non-negotiables, and if you’ve got them right, that is a powerful coaching tool. But if I’m telling everyone to do the same thing, that’s poor coaching. That’s why people are a little bit frightened of someone coming in and saying, ‘This is how you do it’.”

Palmer has faced this resistance because he had made some relatively fine adjustments to methods that have existed for a century and more. Yet England’s greatest run-scorer was rising at dawn and driving halfway across the country to bat on an old tennis court because of what he knew, and that was a powerful thing.

***

Ian Pont played 28 first-class matches for Nottinghamshire and Essex between 1982 and 1988 as a quick bowler, and if he had a claim to fame it was that he could throw a cricket ball further than anyone else. His throw was so powerful, he went to America to try out for various Major League Baseball franchises as a pitcher, and there began to learn some essential truths about propelling a hard ball at high speed.

The Americans were astonished that he had never been coached how to throw. In baseball, it was a fundamental skill, and Pont was taught about the mechanics behind it. He returned to England and had a brief flurry with the javelin, throwing the Olympic qualifying distance of 72 metres, but despite that, and the fact that he could pitch a baseball at almost 100mph, it was cricket that drew him back. As a coach he has led the Dhaka Gladiators to consecutive Bangladesh Premier League titles, worked in the Pakistan Super League with Quetta Gladiators, coached Haryana in India, and, during a spell at Essex as bowling coach, worked with Dale Steyn and Shoaib Akhtar.

”If you look at swimming, people swim faster, if you look at jumping, they jump higher, throwing they throw further, running they run faster. Yet in cricket, we haven’t taught people to bowl faster”

On the day that we talk, he’s driving through a thunderstorm from one game to another, his voice compressed and tinny through the car speaker, rain bouncing from the car roof, his passion for bowling competing with this metallic concerto.

“In the history of sport,” he says, “if you look at swimming, people swim faster, if you look at jumping, they jump higher, throwing they throw further, running they run faster. Yet in cricket, we haven’t taught people to bowl faster? It doesn’t make sense. If you go back to the 1930s, Harold Larwood was supposed to bowl in the 90-miles-per-hour bracket. That’s 80 years ago. What was the 100m record 80 years ago? The technical aspect of every ballistic movement in every other sport – it changes. Fast bowling has never actually changed.”

In the early Nineties, Pont set up shop as a coach with the promise: ‘Bowl Faster or Your Money Back’. He bought a speed gun, and over five weeks worked with 22 club cricketers that all got faster, one of them by 16mph.

Pont on Bangladesh duty in 2011

Pont on Bangladesh duty in 2011

“What I was taught in America was: you throw from your legs, then your hips, then your chest, then your shoulder, then your elbow, then your wrist, and the ball comes out as a consequence of that. It’s like a multi-stage rocket taking off. It was a revelation. And then when I started the javelin, Margaret Whitbread, who was Fatima Whitbread’s mother and a national coach, came down to have a look at me, because I’d done the Olympic qualifying distance on about my fifth throw. She said to me: ‘You have the most natural throwing arm this side of the Iron Curtain, but you’ve got no technique.’ This was the second time someone had said it, and that got me interested. So 30 years ago, as a bowling coach, I wanted to know: can we teach ourselves how to bowl harder, bowl faster, and more effectively? My journey to speed was not through cricket.”

Pont has established the Ultimate Pace Foundation, which teaches his ‘Four Tent Peg’ system. “Over 20 years or so,” he says, “that methodology has been refined into a much more user-friendly way of teaching. And what I’ve discovered is that speed and accuracy go together. They are not mutually exclusive. If your muscles are working efficiently and you are using your body properly, you line up well and everything works.

“Now, take a batsman like Alastair Cook. Over the years he’s made lots of tweaks to his backlift and his stance and so on. When it comes to batting that’s called coaching. When it comes to a bowler it’s called ‘changing’ them. You know, ‘Leave him alone, it’s natural’. Because fast bowing isn’t understood properly and speed isn’t taught, a lot of fast bowlers are left alone. They don’t have the skills that they could have. That’s where I sit as a coach.”

So why does Pont think that he’s outside of the system? “Well, really, I suppose you’d have to direct the question at them,” he says. “When Troy Cooley came to Loughborough [as England’s fast-bowling coach], he did some fantastic work there. In the early years of Loughborough, I did a winter up there and I had a real insight into what the ECB were doing. It was really good with regard to where people bowled, and sports science. But with regard to the increase in speed, we weren’t really looking at that as a governing body. It was more, ‘Can we keep our 85mph bowlers on the field?’ But look, as far as the cricket boards go, my door’s absolutely wide open and always has been. At the coalface, your calling card is your bowlers. Can you make them faster? And that’s what I think I’ve done.”

***

It would be a stretch to call Tony Shillinglaw a coach, although, approaching his 80th year, he has had a lifetime in cricket. When he was 15 years old and playing for North of England schoolboys against the South, he was told that if he wanted to get anywhere in the game, he would have to alter his stance and his grip. When he did he lost whatever it was that had got him there in the first place. He played club cricket at a high level and appeared for Cheshire against Surrey in the Gillette Cup, where he dismissed John Edrich and Ken Barrington with his medium-pacers, but he often looked back unhappily on the compromise he had made.

As Shillinglaw grew older he began thinking more and more often about cricket’s greatest player, Don Bradman, who had been, by the numbers, 30 per cent better than anybody else. And yet Bradman, one of sport’s great autodidacts, had often railed against the orthodox techniques taught by rote, and seemed to be regarded by the game as some kind of unrepeatable cosmic fluke. “Better to hit the ball with an apparently unorthodox style than miss it with a correct one,” the Don hissed.

Tony Shillinglaw has made a study of Bradman’s unique technique

Tony Shillinglaw has made a study of Bradman’s unique technique

Shillinglaw began by converting his garage into a replica of Bradman’s famous porch with its water tank at his childhood home in Bowral. After constant work over several years, he found he was able to replicate – slowly – Bradman’s method, which he called ‘Continuous Movement’ or ‘The Rotary Method’. He began eulogising about The Don, and refused to stop. A couple of years ago, I saw him demonstrate the Rotary Method at his home club Birkenhead Park CC. He used a blue plastic bat and played a mesmerising series of shots with projectiles varying in size from a tennis ball to those small, rubberised ‘jet-balls’ once sold in Woolworths. He co-wrote a book called Bradman Revisited, visited Bowral, and became friendly with Tim Noakes, the South African sports scientist who had worked with Bob Woolmer on The Art and Science of Cricket.

Steve Smith has had success with a comparable method to Bradman’s

Steve Smith has had success with a comparable method to Bradman’s

Noakes began to use some of his PhD students to discover that Bradman’s method was highly favourable for budding T20 cricketers. Shillinglaw’s persistent emails to the ECB paid off when he demonstrated the Rotary Method to Andy Flower at Birkenhead Park. One thing he said stayed with me, above everything else. “At the 1968 Olympics, Dick Fosbury used the Fosbury Flop to win the gold medal and from then on, anyone that wanted to win at high jump had to use his method. And Fosbury himself said, ‘My mind wanted me to get over the bar, and intuitively figured out the most efficient way’. Bradman solved the problem of controlling a bouncing ball in his childhood completely intuitively. He developed a different style of batting which took it to unprecedented heights. The difference between him and Fosbury is that nobody copied Bradman.”

***

So that was to be the thrust of this story. Three very different men, and, if there was a common thread, it was that they were obsessive and driven by a way of seeing the game that didn’t match up with conventional thinking. There are others too, of course. Many of them, most notably perhaps Trent Woodhill – the Australian coach who was central to the development of David Warner, a player whose career path from T20 to Test match batsman has barely been replicated.

Cricket contains multitudes, and with the expansion of the game and the arrival of franchise leagues, there were more opportunities for new lines of thought. Yet Palmer, Pont and Shillinglaw didn’t seem to be advocating for a wider range of knowledge, instead they were diving for deeper, more quintessential truths. Why wasn’t cricket behaving like other sports, and showing an upward curve in the speed of its bowlers? How had one man batted so much more successfully than everyone else? Why had the notion of being side-on in batting existed for so long? There was an interesting crossover too in the work of Palmer and Shillinglaw. The backlift, in both of their methods, was to gully, and the pathway of bat towards ball was similar. Were they approaching the same solution from different directions?

And then things changed.

As the ECB prepared their winter plans for their various squads, Palmer was asked to come along and help, recognition for both his knowledge and his dedication. In Australia, he worked with England’s younger players, as well as Alastair Cook, who rediscovered his form with a record-breaking double-century at the MCG, and Dawid Malan, who made his Test breakthrough in Perth. Steve Smith scored piles of runs, and suddenly everyone was writing about his technical similarities to Bradman, something that Shillinglaw had long been pointing out. And, in the wake of a 4-0 thrashing, England began to examine, again, their lack of fast bowlers, a question that may yet lead to some re-thinking of approach.

Writing in the Times, Mike Atherton pointed towards a future of coaching at the highest level that took a new approach; holistic in parts, but which encouraged new thinking and challenged old orthodoxies. Sometimes what it takes is for an idea to have its moment, to dovetail with the times, and perhaps that has started to happen. Life comes at you fast, after all.