The world-beating West Indies, endless garden cricket and bubblebath Winston Davis beards – Tanya Aldred remembers the summer of 1984 and the arrival of the maroon-blazered galácticos.

First published in 2015

First published in 2015

It was May 1984 – the beginning of my last summer of primary school. Days passed in a haze of handstands and the fear of imminent nuclear war, and televised sport played very little part at all.

But then a crack commando unit arrived at Heathrow. They wore smart maroon blazers and open-necked shirts and were lithe, debonair and quite brilliant. They leant casually against the wall and demolished England’s cricketing straw-hat – an entire tour slipped by from mid-May to mid-August and they lost only one match – a one-day international at Trent Bridge – and as for the Test series, well, 5-0 was polite.

Open Account Offer. Up to £100 in Bet Credits for new customers at bet365. Min deposit £5. Bet Credits available for use upon settlement of bets to value of qualifying deposit. Min odds, bet and payment method exclusions apply. Returns exclude Bet Credits stake. Time limits and T&Cs apply. The bonus code WISDEN can be used during registration, but does not change the offer amount in any way.

They didn’t look like those other sportsmen, often just a Cornish pasty away from elasticated trousers. These guys laughed as they sprang in the air to pluck the juicy red apple from the sky, they high-fived as yet another hundred clocked in, bowled long-limbed Exocets, and topped it all with a rolling strut to win the heart of any pre-teen with taste.

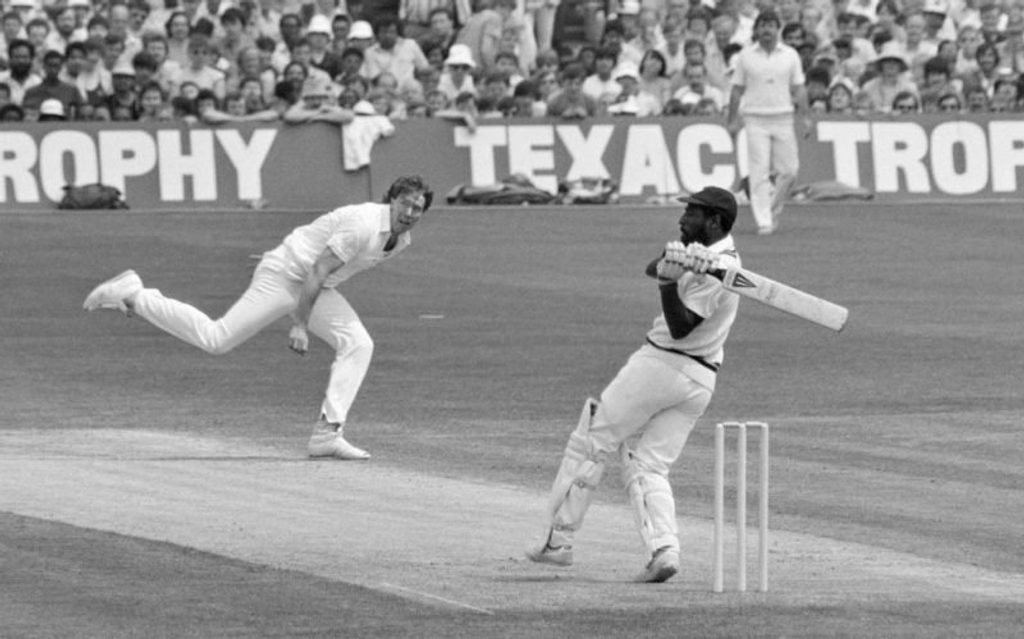

England had endured a dismal winter – becoming the first English team to be beaten by Pakistan and New Zealand, hampered by both injury and accusations of pot smoking. Few thought that the summer would reverse the last three series defeats by the West Indies, and any optimism lasted until, oooh, the first one-day international at Old Trafford when Viv Richards in West Indies cap and Rasta wristband, cocked Duncan Fearnley in his hand, calmly struck one of the greatest one-day hundreds.

Viv Richards was at his belligerent best during his 189* in Manchester. It remained the highest individual ODI score for 13 years

Viv Richards was at his belligerent best during his 189* in Manchester. It remained the highest individual ODI score for 13 years

His 189 not out included a six into Warwick Road station leaving England’s bowlers scuffing the dust and the delighted crowd sprawling out onto all the pavilion balconies. And so it would continue for the remainder of the tour, barring that sketchy and unconvincing win by England at Trent Bridge – which was immediately followed by a resumption of normal service, and another Richards exhibition, at Lord’s.

“I have always felt as a black man that there are so many unfair people out there,” Richards later said. “I wanted to show them that we can climb the mountain too.” The mountain was duly climbed.

***

We watched a lot of the series on our grandmother’s television, a relic even in 1984, which belched when switched on and, in a branch of physics still undiscovered, squashed the picture from the top down. This didn’t render the West Indies any less omnipotent.

From the first match against Worcestershire to the joyous celebration of blackwash at The Oval, West Indies were a team first, just one bulging with individual talents. There was Viv, of course, and Gordon Greenidge, and Roger Harper with his origami arms and Velcro hands and Michael Holding coming off his long run at The Oval and most memorably of all, Malcolm Marshall, at Headingley, playing on with a double fracture of the left thumb. He batted to allow Larry Gomes to complete his century, thrashed a one-armed boundary, then, hand in plaster, beguiled figures of 7-53, his compact little body so fast, so perfect. And in charge of all these blades, Clive Lloyd, a man who at times resembled a weary old dog shuff ling off for one last walk, but who held it all together.

The unbreakable spirit – Malcolm Marshall batting one-handed at Headingley

The unbreakable spirit – Malcolm Marshall batting one-handed at Headingley

There were moments of English dominance – especially at Lord’s, where they were on top until the innings of the summer, 214 not out from Greenidge, led to Gower becoming the first England captain since 1948 to declare in the second innings and lose. Allan Lamb was the rare creature able to counter-attack the West Indies squadron of fast bowlers, with three centuries (only Graeme Fowler made another) and Ian Botham took his 300th wicket. Other than that, the highlight of each Test was the relief that followed when Richards was out.

In between the fourth and the fifth Tests, my dad took my three brothers and me up to Lord’s, to see West Indies play Middlesex. It rained for most of the day but we discovered Joel Garner signing autographs as he perched on the steps of the tour bus, his extendable legs stretched out in front of him, a real life BFG. Cricket’s allure had by then soaked through our pastel coloured windcheaters. In the bath, my brothers patted bubbly Winston Davis beards into place. We collected the Texaco Trophy caricature cigarette cards – which slotted pleasingly into a green paper folder. And after school the early evening highlights became routine viewing.

My parents had bought an old house with a big garden the previous year – and all summer we were outside. When my brother Sam was forced to wear a sling after an insect bite became infected he became a perfect stand-in for Paul Terry, who, left arm broken trying to avoid a ball from Winston Davis at Old Trafford, came out to help England save the follow-on. And amid scenes of confusion, had to face Garner with his arm in plaster. My middle brother Toby protected his head from a barrage of tennis balls with his CHIPS (Californian Highway Patrol) helmet that he had unwrapped the previous Christmas. It wasn’t actually a bad homage to the head protection England were hiding behind.

West Indies fans celebrate the 5-0 “Blackwash”

West Indies fans celebrate the 5-0 “Blackwash”

The summer ended with a one-off Test against Sri Lanka which was supposed to provide light relief but ended in further humiliation. Gower invited the Sri Lankans to bat, and had to watch them do so for two days with centuries from Sidath Wettimuny and Duleep Mendis. Only the ever-reliable Lamb scraped much dignity from the situation; England were even booed by the Lord’s crowd for slow scoring on the Saturday afternoon.

That West Indies side of 1984 was unbeatable in a way that must be unimaginable to children who follow cricket today. They were the All Blacks and Real Madrid combined – with the same fear and excitement but more grace, perhaps more joy, and certainly fewer financial endorsements. It was both political and awesome. What I didn’t realise as a child, was that these men were all-time greats, at their all-time prime. What luck, to stumble on them that long hot summer.