Phil Walker charts the story of cricket commentary through a selection of some of the classic calls in the game’s broadcasting history. This article was first published in issue 67 of Wisden Cricket Monthly, guest-edited by Isa Guha.

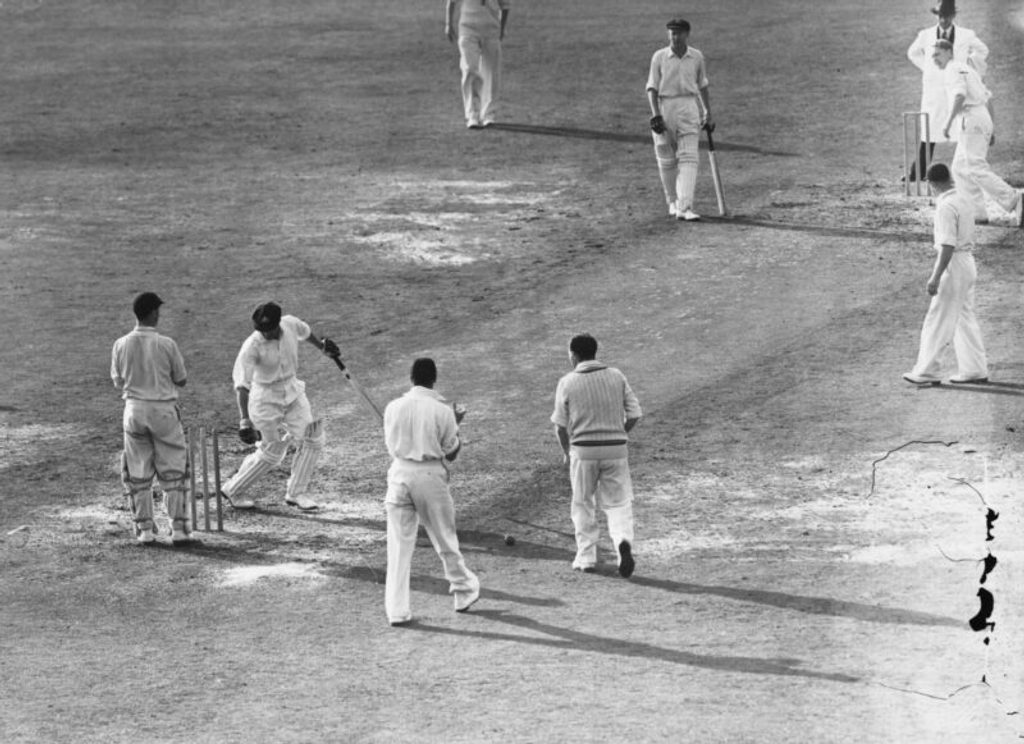

Howard Marshall | England v Australia, Lord’s, 1934

The 1920s was one of cricket’s great leaps forward. The Golden Age was fading. Ashes tours had become big business, the West Indies were mobilising, and a boy-genius from uptown New South Wales was having great sport with a stump and a golf ball. For an Australian public desperate to connect with their national obsession, the formal establishing of radio stations in 1923 would be a godsend.

No doubt, Test cricket commentary originated in Australia. The first ever recorded broadcast had taken place at Sydney in 1922, for a testimonial game to celebrate the career of Charles Bannerman, Test cricket’s first centurion. Sadly no recorded evidence exists, nor for the broadcast that would follow for the Sydney Test of the 1924/25 Ashes, when Len Watt and the former Aussie left-hander Clem Hill were asked to give a report on the state of play and the studio announcer told them down the line just to keep going. The first ball-by-ball coverage would occur later in that series at Adelaide, when Bill Smallacombe, station manager at Adelaide radio station 5CL, performed the considerable feat of commentating on his own for all seven days of that Test match. The Adelaide faithful were the sole beneficiaries of his efforts, but while the technology was in its infancy, and those early hits were stuttering efforts delivered via a single microphone positioned next to a sightscreen, the notion of bringing live cricket commentary into Australian homes had begun to take hold.

“It’s the old ‘tyranny of distance’,” explained Jim Maxwell, the legendary voice of modern Australian cricket on the radio, on Calling The Shots, the definitive podcast of cricket commentary. “That and the Bradman phenomenon. Getting to the ground in those days was only really for those who lived in the city or that state. It was a way of getting the message across to the whole nation. Everyone wanted to hear what Bradman was up to.”

Before too long, word of the revolution would reach the control rooms of the British Broadcasting Corporation.

As the head of outside broadcasting at the BBC, Lance Sieveking understood the value of sport. The man whom John Arlott later called “the outstanding and most creative pioneer of British broadcasting” had already produced the first rugby union internationals and been credited with drawing up the eight-squared grid that formed the basis of early football commentaries. After hearing baseball commentary in the US, he went about convincing the establishment that the same could be done for cricket.

The press were initially hostile to the idea. The Radio Times said it would be impossible. The Guardian scoffed. While at Lord’s, the rumblings were barely quieted when Plum Warner delivered, questionably, the first broadcast from the roof of the ground’s clock tower. By the turn of the decade, however, attitudes were shifting.

The BBC covered elements of the 1930 Ashes in England, while those matches were covered in Australia by cabled reports. These ‘synthetic’ reports – involving local commentators calling the action ‘as live’ from delayed ball-by-ball cables – proved so popular that when the return Bodyline series caught fire the BBC went all in, broadcasting reports from the former Australian player Alan Fairfax, who would deliver his own interpretative commentary based on the cables from a Poste Parisien radio studio high up in the Eiffel Tower.

By 1934 the BBC was ready to provide full, detailed coverage of Test cricket, and Sieveking had the ideal man to realise his vision. “Howard Marshall had the perfect voice and disposition for covering Ashes cricket,” the former Test Match Special producer Peter Baxter told Calling The Shots, and listening to Marshall now, with his tonal variations and eye for the evocative (“Bowes walking slowly, purposefully, back to his pile of sawdust”), its rhythms sound almost eerily contemporary. He was fortunate to have a good series to cover, too: while Bradman bestrode the summer, the Lord’s match was the scene of Hedley Verity’s 15-for, and Marshall’s call at the end of that match, notwithstanding the uniformly plummy vowels of the time, would not be out of place in the commentary booths of today. Cricket had its model for radio. Let the shows commence.

John Arlott | England v Australia, The Oval, 1948

No single piece of cricket commentary is more famous, more sparse, nor more debated. While it’s broadly accepted that John Arlott’s halting 16-word account of Bradman’s final act could never happen now, some would argue that it wasn’t that great for the time either. One thing is not disputed: Arlott’s words remain, then as forever, inseparable from the moment itself. Landmarks would have their soundtracks, and the gravelly, tobacco-tinged Hampshire tones of the sombre Arlott, the son of a cemetery manager and a former policeman, Japanese POW and published poet, were synonymous with the cricket of the time.

If the instant reaction to Bradman’s fall verges on the monosyllabic, Arlott gathers himself with sensitivity and astuteness in the moments after, wondering if perhaps even Bradman was unnerved by the grandeur and gravity of the occasion.

“How… I wonder if you see the ball very clearly in your last Test in England, on a ground where you’ve played some of the biggest cricket of your life and where the opposing side has just stood around you and given you three cheers, and the crowd has clapped you all the way to the wicket… I wonder if you really see the ball at all.”

If Arlott and his sprightly colleague Rex Alston were the voices of post-war English cricket, then Alan McGilvray’s belonged to Australia. McGilvray was a born broadcaster. Even as captain of New South Wales, he was partial to delivering close-of-play reports from games in which he was playing. He was sent by ABC to cover the ’48 series and was thereafter a fixture in the commentary boxes of the world, broadcasting over 200 Test matches until his retirement at the end of the 1985 Ashes, signing off with the line, “Well, that’s my story”.

Don Bradman, b Eric Hollies, 0

Don Bradman, b Eric Hollies, 0

The journalist EW Swanton described him as the most professional of commentators, “in that he was essentially a meticulous communicator of fact… his commentaries were instantly distinctive because his Australian intonations were almost whispered into the microphone, too quietly sometimes to be heard by his colleagues in the broadcasting box”.

There was no love lost in Arlott and McGilvray’s labours, after an early incident when McGilvray overheard the Englishman being less than kind about his commentary style. From that point on it was necessary for producers to ensure that neither man followed the other in the running schedules.

They were different too in outlook and attitude; McGilvray was a staunch traditionalist who abhorred what he saw as Arlott’s lofty indifference to the rudiments of the job. “He [Arlott] was a good commentator in his own way, but he didn’t give the score or the card. You should give the score three times in a six-ball over. He had a different technique to mine, more intimate, but he didn’t care about the Aussies not listening – a lot of what he said was way above their heads.”

Something else would separate them. While Arlott moved into early TV work, commentating in much the same style on the early years of the John Player Sunday League, McGilvray, a purist, was less enamoured with the direction of travel. Kerry Packer’s late-Seventies TV power grab was such anathema to him that he wrote a book about it, The Game Is Not the Same (1987). It became a bestseller

Richie Benaud | England v Australia, Old Trafford, 1993

Benaud was an industry in himself. A former captain of Australia, a strategist ahead of his time, and a velvet-voiced master of the mic who came to be the face and much-mimicked voice of cricket broadcasting in England and his homeland. The library of Richie-isms is vast, and you will likely have your own favourite. “His pronouncements, carefully rationed, were widely regarded as gospel,” wrote David Frith when Benaud died in 2015 aged 94. “Such guarded humour as he evinced bore the touch of a man who was keen to be seen above all else as discerning.”

The leg-spinning lineage running through Benaud to Shane Warne had been established before Benaud settled into the BBC TV chair to call Warne’s first Ashes delivery, but with that ball the bond was secured. Whatever Warne did, Benaud was there to illuminate. His response to the Gatting ball is almost comically understated, yet that last line, a trademark side-of-the-mouth witticism, nonetheless captures the sense of discombobulation that envelops a cricket field when someone does something extraordinary. As a leggie, Benaud knew what that delivery said. As a commentator, he let it talk for itself.

He was still at it in 2005, steadying the nerves across that cinematic summer (“Oh Stephen Harmison, with a slower ball, one of the great balls!” – Nicholas), and while the commentary boxes of Australia had by then become a little cramped for Benaud’s style – this was not a man to shout to be heard in an overcrowded bar – he was revered to the end, closing out his stint England with timeless class at The Oval. “It’s time to say goodbye, and to add: thank you for having me. It’s been absolutely marvellous for 42 years. It’s been a privilege to go into everyone’s living rooms, and a great deal of fun…” After which follows the briefest pause, as McGrath runs in to bowl to Pietersen. “But not so for the batsman. McGrath… has picked him up.”

Bill Lawry | Australia v West Indies, Perth, 1997

Kerry Packer’s fingerprints have stuck to cricket ever since he first grabbed hold of it in 1977 with the infamous challenge to Australia’s autocratic establishment: “Come on now, we’re all harlots – what’s your price?”

The Packer revolution, as it’s come to be known, would be broadcast live on his own Channel Nine, ushering in a new style of cricket coverage that still thrums to the rhythms of today. “It was perceived at the time as a commercial heist,” said Mark Nicholas on Calling The Shots, “and it was only when people understood that he had a true love for the game that they began to realise there was something behind it. He had night cricket in his head, he had the white ball, he had the coloured clothes, they were all in Kerry’s head. Kerry had the eye for television.”

With Australia’s best players signed up to Packer’s breakaway World Series Cricket, he assembled a dream commentary line-up of Richie Benaud, Bill Lawry, Ian Chappell and Tony Greig. The four would combine for the next few decades, reshaping the art of TV commentary. “No cricket commentary team has been able to match the original Channel Nine four,” says Nicholas, “and everything is compared back to them.”

Lawry and Greig were as close as cricket broadcasting got to a double act. They had a deep friendship, natural comic interaction, and impeccable credentials, as former Test captains. Greig was bolshy and ebullient, while Lawry was a master of light and shade – considered and analytical when the moment called for it; unhinged for the big stuff.

They both understood the value of the catchphrase. From Lawry declaring another cricket ground to be “ON FIRE” to Greig sending off another batter with a “Goodnight Charlie!”, they honed their own signature lines to amplify the theatrical. There are many moments to pick from, but for a slice of unadulterated Lawry, set to a backdrop of Curtly Ambrose running through Australia’s tail at Perth, the above takes some beating.

Ian Bishop | West Indies v England, Bangalore, 2016

The global game, fragmented and disparate and sprawling, now has a travelling troupe of diverse voices to articulate it.

Many of the best now flock to the game’s commercial epicentre, where the world’s grandest circus continues its inexorable expansion and coteries of great old boys wear their elevated status on a nightly basis.

In among them is the silver-tongued encyclopaedia Harsha Bhogle, unique among the big beasts in never having played at the highest level but as central to the articulation of the Indian experience as any. He’s a dying breed, he says. “I am the last of my type – there will never be another me,” Bhogle once told WCM. “It is impossible. Because people are not giving those who haven’t played international cricket a break. I was very lucky to come in at the time that I did.”

“Stephen Harmison with a slower ball”

“Stephen Harmison with a slower ball”

Still, as the landscape shifts like a swiftly shaken etch-a-sketch, there is still space for an explosion of old-style partisan joy, and all the more potent and moving when it’s delivered by a commentator as discerning as the Trinidadian, Ian Bishop. His call at the end of the 2016 T20 World Cup final – a pitch-perfect synergy of words, pictures and moment – was only made possible because Bishop’s co-commentator David Lloyd cleared the airwaves for him to take over. In that moment of crazed tension Lloyd recognised that this was a West Indian thing.

Bishop, along with Michael Holding and latterly Fazeer Mohammed, form a magical Caribbean cohort that began with Tony Cozier, the conscience of West Indian cricket and its most distinctive voice. Test Match Special’s Daniel Norcross wondered in the pages of The Nightwatchman if Cozier might be the most complete of them all: “Diligence and professionalism, whilst being admirable virtues, do not explain the unique quality of his commentary style. Rather it was that the watcher or listener was transported to a beguiling, exciting, familiar but transfixing place whenever he was on commentary. His voice evoked memories of the first time you heard it while firmly placing you in the here and now.”

Mel Jones | Australia Women v India Women, Melbourne, 2020

While radio remains a constant hum in the ear, TV tends to gobble up the big moments. Picture Ben Stokes’ one-hander at The Oval on the first day of the 2019 World Cup. Who doesn’t hear Nasser Hussain, utterly flabbergasted, in thrall to, yet on a certain level offended by, the sheer brass of Stokes’ audacity? And no mention of that tournament’s final seconds is ever complete without recourse to the barest of margins, a line so perfectly weighted by Ian Smith, so fair and humane and – in the chaos of his own emotions – journalistically astute, that whenever it’s used again out of its original context it transports the listener back to that very moment, a call-back to the endlessly magical.

“Build the man a statue!” – Mark Howard’s line after Scott Boland’s sixth Ashes wicket at the MCG is another contemporary classic from a bold new voice of the modern era. Howard epitomises the new style of Australian commentary, first with the BBL on Network 10 and now with Fox Cricket, where the use of headsets, having three people on at once and the feed being more knockabout and conversational has become the prevailing tenor of their coverage, and where Mel Jones, also on the roster at Fox, has become arguably the most authoritative female caller in the game, the frontwoman of a new band of ceiling-busting voices that are reshaping the whole experience.

From Alison Mitchell and Ebony Rainford-Brent to Natalie Germanos, Lydia Greenway and our very own guest editor, female voices are shaking up the game, opening it up to new audiences while dismantling the prejudices that have hung to parts of the old. Jones, says Isa Guha, who’s seen her work up close, is right up there with the best. “Her line in the 2020 women’s final is iconic. And that was such a pivotal moment for the sport.”

Jonathan Agnew | England v Australia, Headingley, 2019

For all that, nothing quite compares to radio when it’s done like this. “Aggers at his best,” says Norcross (who knows of what he speaks). “His timing is perfect. His urgency. His pause. A masterclass, really.” Howard Marshall would no doubt have agreed.