Aadya Sharma breaks down Malinga’s ODI career into three phases and is astonished by what he finds.

After 15 years replete with yorkers, from toe-smushers to clever, slower ones, Lasith Malinga left a lasting impression on ODI cricket, and bows out as a modern-day genius of the white-ball game.

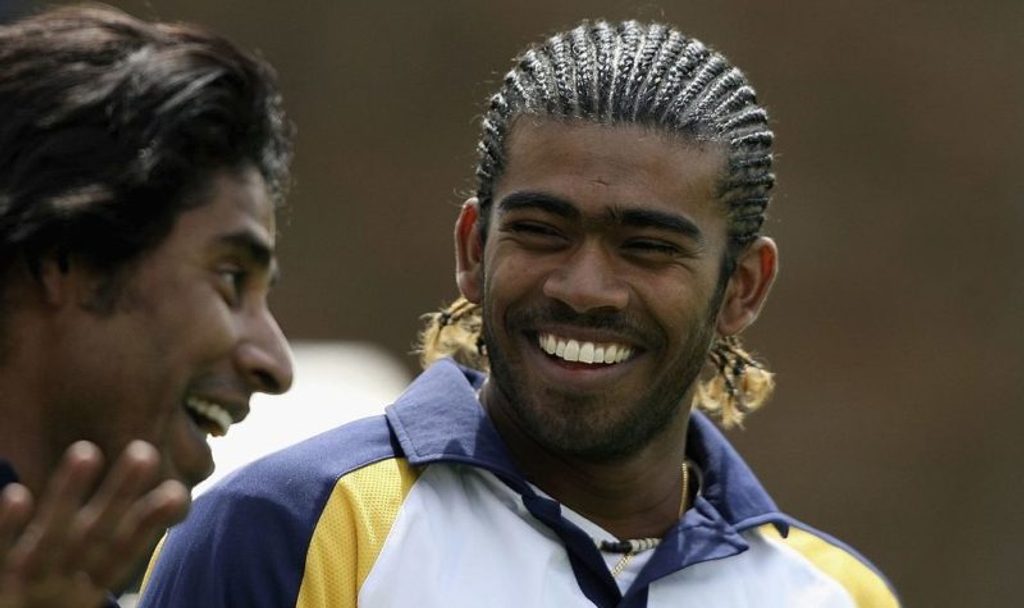

Right from his formative playing days, Malinga was deemed an outlier, courtesy his quirky bowling action. His biggest challenge, therefore, was staying true to his identity. The ‘Rathgama Express’ faced several obstacles, but shape-shifted his way out of each of them with an array of variations.

Breaking down his ODI career into three broad phases, we see how much Malinga adapted, but how little he changed.

2004 to 2006: Finding his feet

When Malinga first entered, Vaas was Sri Lanka’s unchallenged spearhead

When Malinga first entered, Vaas was Sri Lanka’s unchallenged spearhead

A scrawny Malinga was handed his ODI debut in Sri Lanka’s 2004 Asia Cup triumph, the first of many white-ball honours that came his way. At the time, Chaminda Vaas was Sri Lanka’s pace spearhead, enjoying a second wind following a stellar 2003 World Cup.

Malinga’s first two years in ODI cricket went by in a flash – he played just five ODIs till 2006, even as his red-ball exploits turned heads.

Initially, it was Malinga’s unique action that caused problems for batsmen. The slinging arm, invariably right-angled to the rest of his body, was a far cry from the conventional upright release, meaning the hard white ball had a scrambled seam.

Congratulations on a wonderful One Day career, #Malinga.

Wishing you all the very best for the future. pic.twitter.com/RLeKIudyWl— Sachin Tendulkar (@sachin_rt) July 26, 2019

At 5’8’’, Malinga’s bent knees brought down his release points ever lower, and to his credit, Malinga never tampered with this aspect of his game.

His dipping yorkers, employed primarily at the death, broadly branched into two categories: The quicker one seared off the arm and hurtled towards the base of the stumps, while the other, a cheeky slower one, twirled through the air, trapping batsmen in front of the sticks.

2007 to 2012: The Lankan messiah

Malinga’s feat of four in four remains unmatched in ODI history

Malinga’s feat of four in four remains unmatched in ODI history

Malinga’s brilliant ODI versatility was at the forefront of Sri Lanka’s run to the final of the 2007 World Cup. It was most evident during his 4-54 against South Africa, remembered for his unmatched feat of claiming four wickets in as many deliveries.

The first and fourth ball, pitched almost identically on the middle and leg stump, were delivered at 135.9 kmph and 144.7 kmph respectively, highlighting a distinct difference between his two kinds of yorkers.

Through his spell, a dot-ball percentage of 58.9, and a boundary percentage of just 14.28, denoted an ability to sustain pressure by interspersing his wicket-taking deliveries with dot balls.

An honour to play with you and an honour to play against you! LEGEND ? pic.twitter.com/SMjpeOaziV

— Jasprit Bumrah (@Jaspritbumrah93) July 6, 2019

Contrary to other quicks, Malinga was at home on sluggish tracks, perhaps due to the days spent in his childhood bowling with tennis balls on sandy Galle beaches. As age caught up, he traded his cannon hurling for canny catapulting, but never shelved his mantra of channeling deliveries on the stumps.

He began the 2011 World Cup annihilating Kenya in Colombo, returning 6-38 – his best ODI figures to date. What Malinga subjected the Kenyan batsmen to is something that became his trademark: he hurled full and straight deliveries at the batsmen’s toes, repeatedly.

Malinga claimed his career-best figures of 6-38 against Kenya, yorking out six batsmen

Malinga claimed his career-best figures of 6-38 against Kenya, yorking out six batsmen

Astonishingly, his six wicket-taking deliveries, all yorkers, were within the range of 143.32 kmph and 144.24 kmph. It showed his remarkable control over a delivery considered extremely difficult to execute.

In chases, Malinga’s spells would dial down the flow of runs. When not hurling yorkers, he would shrewdly force false shots with subtle change in pace.

Months after the World Cup, Malinga rattled Australia in their chase of 287 during a bilateral series in August 2011, prising out five victims for merely 28 runs in Hambantota. Four of them exited through false strokes. His average speed in the spell was 136.52 kmph, with an astonishing dot-ball percentage of 74% and a boundary rate of a mere 6%.

Interestingly, his personal success mirrored Sri Lanka’s ODI fortunes in that period: two successive World Cups finals in 2007 and 2011 [averaging 15.77 and 20.76 respectively], while he was joint-top of the wicket charts in the 2014 Asia Cup.

2012 and beyond: Bruised, but not broken

Malinga’s variations lived through the two new-balls rule [introduced in 2012] that stymied late reverse swing – he therefore banked on late dip, rolling his fingers underneath the ball to execute it.

At the 2013 Champions Trophy, Malinga’s spell of 4-34 in New Zealand’s chase came with a dot-ball percentage around 73.3 [identical to the Hambantota chase], while his average speed was 135 kmph.

Malinga’s variations lived through the two new-ball rule, introduced in 2012

Malinga’s variations lived through the two new-ball rule, introduced in 2012

Between the 2007 and 2011 World Cups, Malinga’s debilitating knees caused problems – a swollen knee bone meant he could barely climb stairs – and he appeared in just 19 of the 51 ODIs in 2008 and 2009. He fought through that phase, but injuries caused more problems after 2015 as well, and this time, he had to make a sacrifice: his pace.

Between 2011 and 2013, Malinga consistently crossed 140 kmph, and clocked a top speed of 155 kmph. From 2015 to his last World Cup game, Malinga bowled exactly seven deliveries over the 140-mark, with a maximum speed of 145. That was a function of age, but he adapted here as well, with increased use of the slower ball on sluggish surfaces.

His last five-wicket haul, against England in 2018, indicated several aspects of this revamped approach. His average speed during the five dismissals ranged 118.76 kmph, three of which were yorkers.

Lasith Malinga with his family following his final career ODI ???? ❤️ pic.twitter.com/En7vzN7ctK

— ICC (@ICC) July 27, 2019

In the 2019 World Cup, Malinga’s speeds dropped further – he did not bowl a single delivery over 140 kmph. Throughout the tournament, he averaged 126.52 kmph. Yet, he remained effective against the best opposition – Sri Lanka defeated eventual champions England – thanks to his cunning variations.

In his spell of 4-43 against England, his average speed hovered around 127 clicks, with his slowest delivery dropping as low as 103.68 kmph.

Yet, more than half [32] of his deliveries were directed on the stumps – even in his last few matches, he never wavered from his tried-and-trusted approach of targeting the sticks. He sent down five yorkers, all of which were dot balls in that match.

A 35-year-old Malinga turned back the clock at Leeds with figures of 4-43

A 35-year-old Malinga turned back the clock at Leeds with figures of 4-43

In his seven games at the World Cup, the 35-year-old Malinga’s dot-ball percentage was 51.7 – only 12.46% of his deliveries went to the fence.

Between 2007 and 2012, Malinga’s yorkers had a dot-ball percentage of 60.4, and a boundary percentage of 4.87%. After 2015, the reduced speeds did little to affect his yorker – the dot-ball percentage was better at 63.57%, while the boundary percentage dropped to an astonishing 2.58%.

Malinga’s trust in his own abilities, and the effectiveness of his methods, stayed independent of his ageing body and diminishing speed. His 259 wickets in 173 games is the most by any ODI bowler in the last 10 years. This, despite him missing out on 70 of Sri Lanka’s last 122 ODIs over the last five years.

Malinga can now proudly look back at his legacy: constantly adapting, never quite changing.

CricViz numbers were incorporated in this analysis.