They call Port Elizabeth ‘The Friendly City’. Well, Keshav Maharaj does.

CricViz’s Ben Jones analyses the work of the spinner on day one of the third Test between England and South Africa.

They call Port Elizabeth ‘The Friendly City’. Well, Keshav Maharaj does.

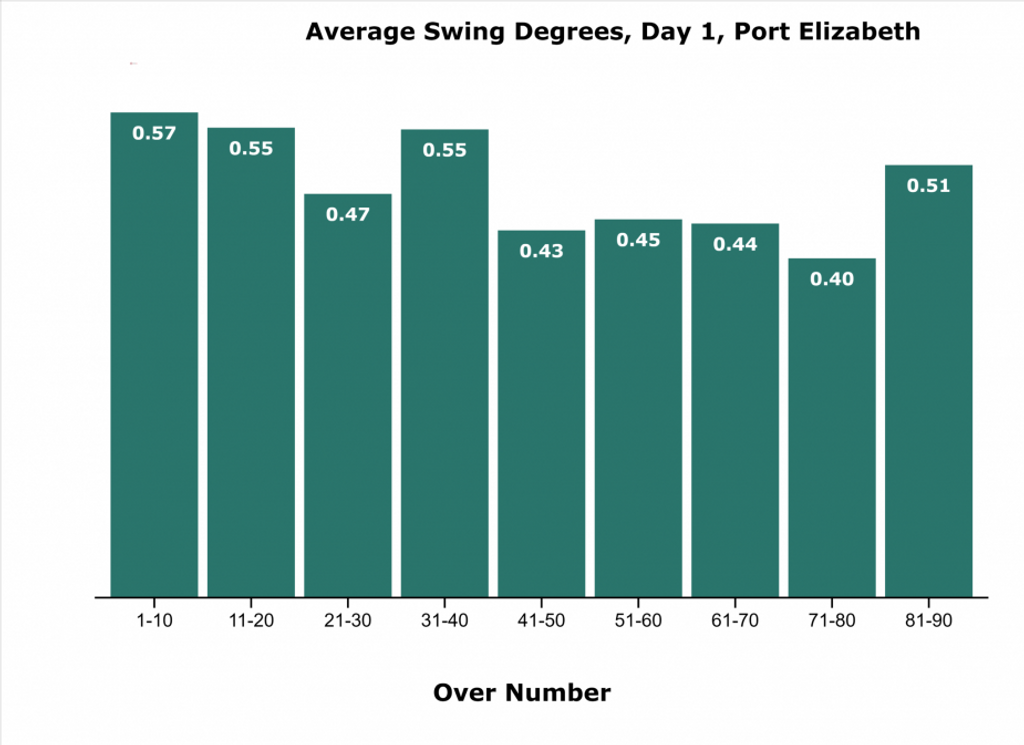

Ahead of play in PE, many noted the abrasive nature of the surface, and anticipated reverse swing playing a factor. It’s a tough gig reading pitches before a ball has been bowled, and given what was in front of the assorted ex-skippers and educated onlookers, that was a fair assessment. Swing looked as if it was going to be the threat.

However, it wasn’t. The seamers found 0.5 degrees of swing, on average, the second-lowest ever recorded on day one of a South African Test. Dom Sibley and Zak Crawley saw off the new ball and, after England’s longest opening partnership on day one in around a decade, the time arrived for reverse. Except it didn’t arrive. A few signs of tail, a bit of shape here and there, but nothing substantial. The main threat was going to have to come from elsewhere. It needed to.

For Faf’s sake, it did. The flipside of the dry, abrasive surface is that whilst it negates the stand-the-seam-up quicks, it brings spinners into the game earlier, and that’s exactly what we saw.

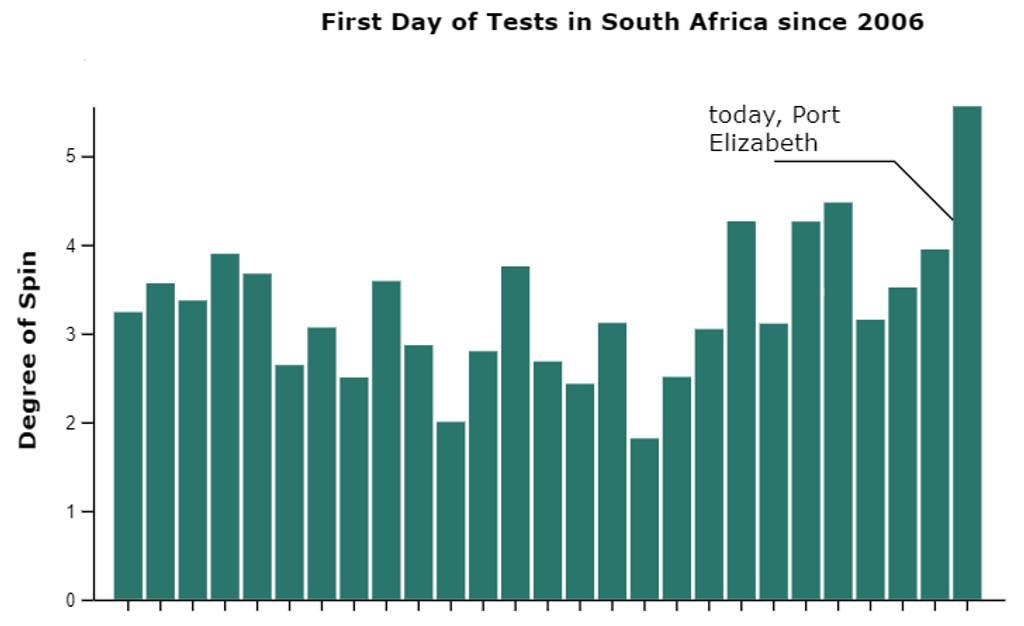

Maharaj found an average of 5.6 degrees of spin today in Port Elizabeth. That’s a serious amount given that in South Africa Tests Maharaj typically averages 1.5 degrees of turn. Today was a treat. He’s more than used to operating in such conditions, and has found a way to succeed without enormous movement off the pitch but, today at least, Maharaj was met with unprecedented help from the surface.

In fact, it was a historic amount of assistance. Not since ball tracking data has been recorded (2006) has a pitch in South Africa spun as much on day one of a Test. Typically, with these sorts of stats, the man responsible is a ripping leg-spinner, some round arm hard-spinning wristy-sacrificing accuracy for revs. Yet here was a finger spinner bowling around 84kph getting big, consistent spin off the pitch. This was never going to be a straightforward day for the batsmen, though as it turned out, not for the reasons we expected at the start of play.

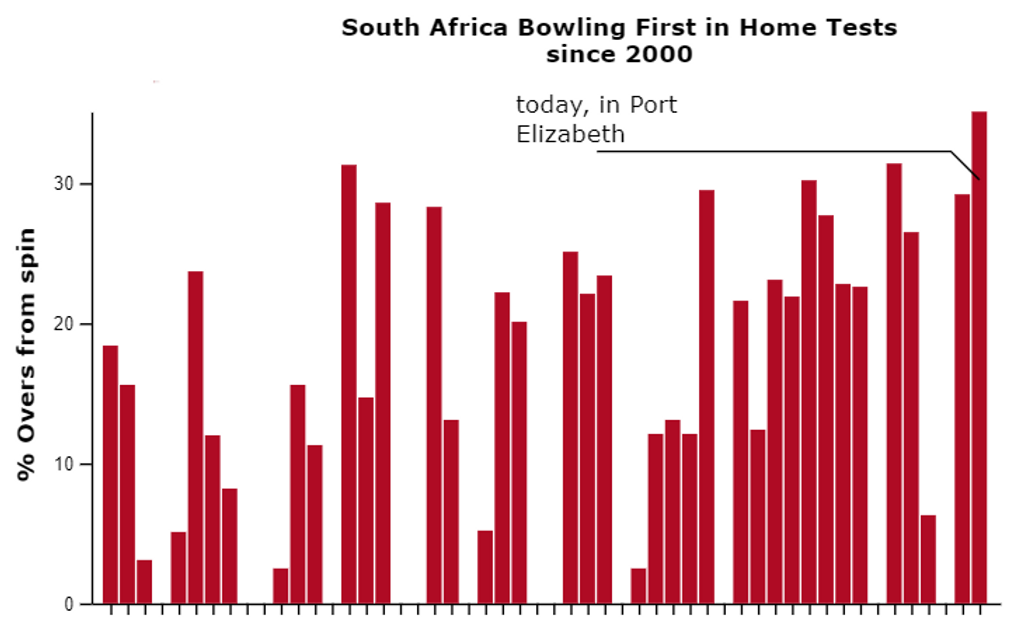

To his credit, du Plessis recognised this, and went with it. Philander was thrown into the outfield for all of the day barring a few short and not-so-sharp spells, with Maharaj bowling unchanged for a remarkable chunk of the day. Thirty-five per cent of the balls bowled by South Africa were from spinners – that’s the highest percentage in the first innings of a home Test this century.

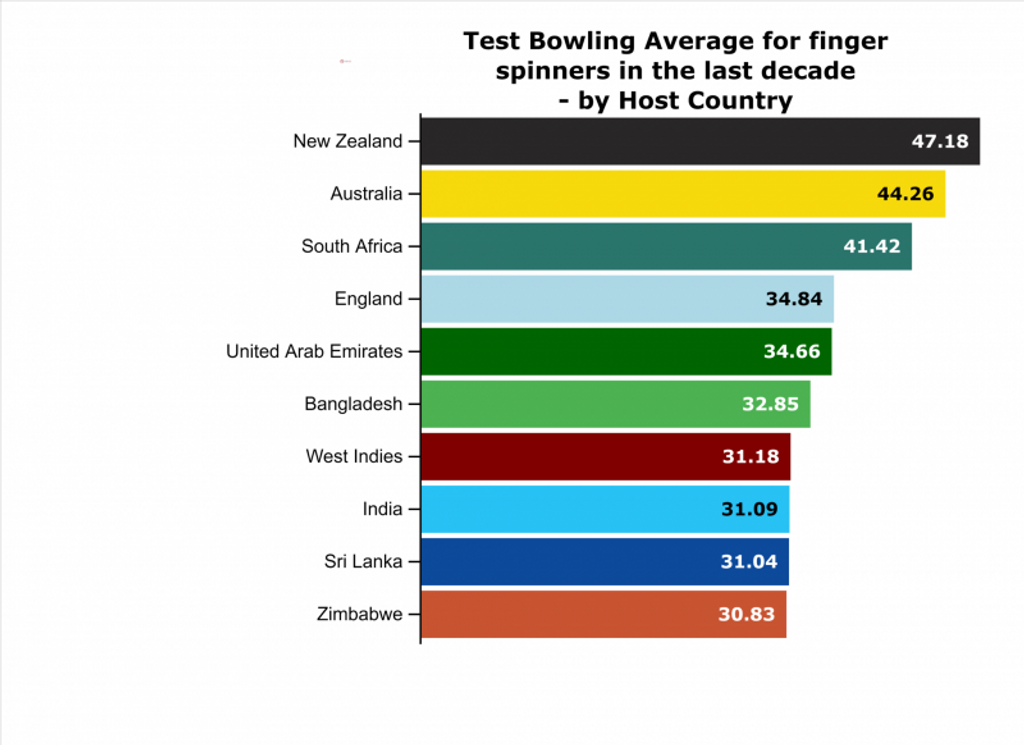

It’s not been an easy life as a finger spinner plying your trade largely in South African conditions. Wickets are more expensive there than almost anywhere else in the world. Maharaj had earned this, and he was making the most of it.

He had Joe Denly cornered. The English No.3 faced 62 balls from Maharaj, scoring just three runs before being dismissed – an attractive and crowd-pleasing run rate of 0.3rpo. Denly may have only played three false shots – one bringing the dismissal – but he was straining to remain secure. A stalemate between spinner and batsman on the first day of a Test match feels like a win for the bowler.

And yet, that wicket of Denly was the only tally in the wicket column for Maharaj at the end of the day. For all that turn, and admirable control, he hadn’t exactly ran through the tourists’ line-up.

Of course, that doesn’t tell the full story. According to our Expected Wickets model, the deliveries that Maharaj bowled would – on average – have taken 3.2 wickets. In part, the England’s solid defence is responsible for that difference. Root’s men clearly went out with determination to bat time and a willingness, where necessary, to resist any urge to accelerate the scoring. They were content to soak up pressure, and to leave runs out there – our model suggests that Maharaj’s deliveries would normally have gone for 86 runs, whereas England only took them for 55.

That was the trade-off England were willing to make. It defined the day.

Because that pattern was extrapolated across the whole action. The deliveries South Africa bowled today should, on merit, have taken 9.4 wickets, at the cost of 262 runs. England should have been in deep in it, but with a few on the board. That would fit the pattern of recent times, for this England side. It would have been an outcome South Africa settled for in an instant, when Joe Root called correctly at the toss. Yet England resisted. Fourty-one per cent of the strokes they played today were defensive strokes – the last time they played more on day one of a Test was on the India tour in 2016. There was a concerted effort, throughout the side, to defend. The merits of that decision are up for debate, but it is clear that England took a clear choice. They were going to leave runs in the middle, and take wickets to bed.

Such is a bowlers lot, tomorrow Maharaj will have to come back and do it all again, lay down that bet for England, invite them to twist when they really should stick. This England side don’t really make big scores batting first, but will be eager to change that habit – another session of grinding away could very quickly turn into some Stokes/Buttler fireworks if South Africa aren’t careful.

Ben Jones is an analyst at CricViz.