Spinners are the most effective – yet least used – bowlers at the death in T20 cricket. Why? And which IPL teams can exploit it in 2018? Ben Jones of CricViz provides fresh analysis for Wisden.com.

CricViz are cricket intelligence specialists

The early stages of the 2018 IPL have seen some bruising figures at the death. Dwayne Bravo’s mauling at the hands of Andre Russell saw him concede 40 off 12 deliveries. His Chennai teammate Mark Wood was also taken apart by Krunal Pandya, with 36 coming off the Durham man’s two overs. Mitchell McClenaghan was taken for 20 off a single over. Even the great Jasprit Bumrah is going at 14.5rpo in the closing stages so far.

Of course, what all these bowlers have in common (aside from all appearing in the nerve-shattering curtain-raiser between Mumbai and Chennai) is that they are all seam bowlers. Despite the fact that when they have bowled, the spinners have been mightily effective at the death (and that the top seven ICC ranked T20 bowlers in the world are all spinners), just 19 per cent of the death bowling in the IPL so far has been from spin.

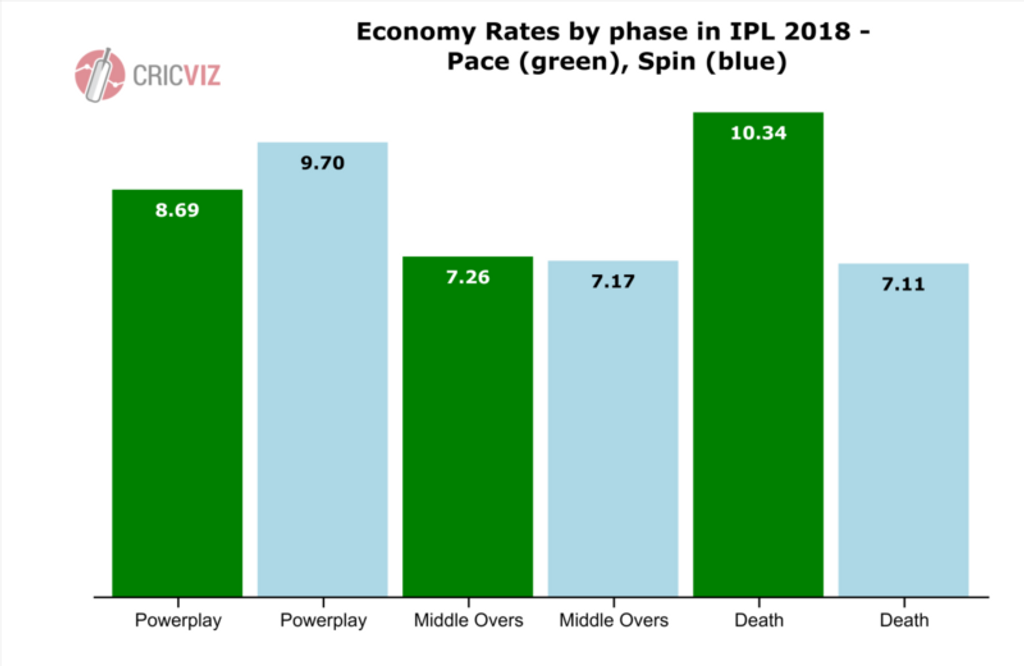

This isn’t new. In the last year, just 16 per cent of deliveries at the death (overs 16-20) have been bowled by spinners, compared to 36 per cent in the innings as whole. Yet over that time period, spin has been more economical than pace at the death in every single major T20 tournament around the world.

That’s right – even with the vastly varying conditions globally, the fluctuating quality of batting from competition to competition, not one tournament has seen spin punished to a greater degree than pace at the end of the innings. In a wider sense, the effectiveness of the slower bowlers in T20 cricket has never been more widely accepted – with one notable exception. Why aren’t they trusted at the death?

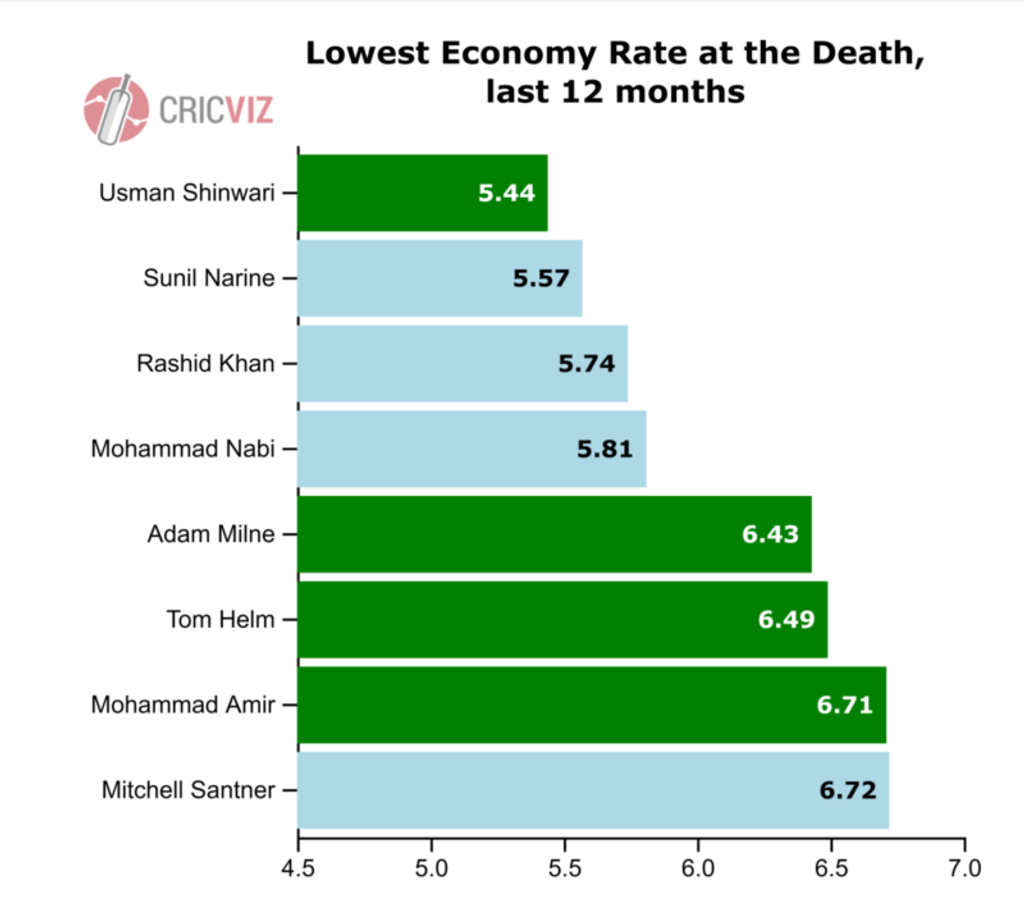

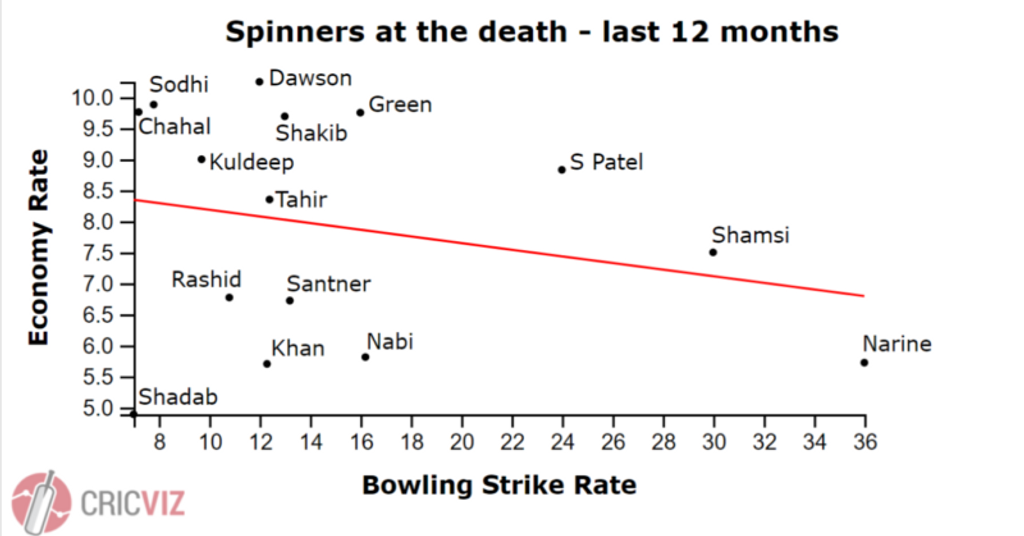

Interestingly, despite the lack of opportunities, and an almost structural obstacle to overcome in the form of accepted wisdom, the cream has still risen to the top. Of the eight most economical death bowlers over the last year (minimum 60 balls), four have been spinners.

The two men at the top of that list are the major trailblazers. In fact, Khan and Narine have bowled 13 per cent of all spin deliveries at the death over the last year.

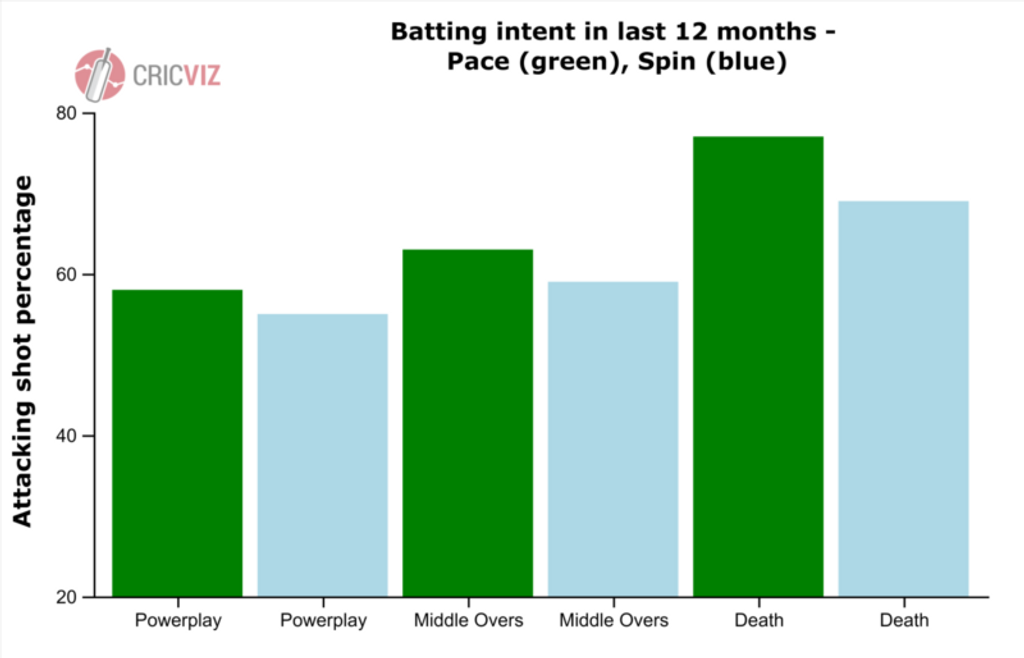

So why are spinners more economical at the death? The data suggests that it’s only partially to do with a lack of intent on the part of the batsman. Batsmen do attack spinners less at the death, but broadly, as the graphic below shows, the increase in attacking intent from batsmen as they move into the death overs is the same regardless of whether they are facing quick bowlers or slow bowlers.

The difference in scoring-rate when attacking is also negligible. Batsmen score at 9.8rpo when attacking spin, and 10.21rpo when attacking seam. The more obvious differential comes when looking at the scoring rate when rotating – ie attempting ones and twos. Rotating seamers, batsmen are able to score at 5.95rpo, almost a run-a-ball – against spin, this drops to 5.02rpo.

Given this clear undervaluing of spin bowlers in this period, one is inclined to ask how the world’s collective cricketing intelligence let this potential innovation slip through their fingers? Every single team in the IPL has a spinner in their squad who’s bowled at least four death overs in the last year. They all have options. So why aren’t captains bowling them?

Sunrises captain Kane Williamson has death spinners at his disposal. Will he use them?

Sunrises captain Kane Williamson has death spinners at his disposal. Will he use them?

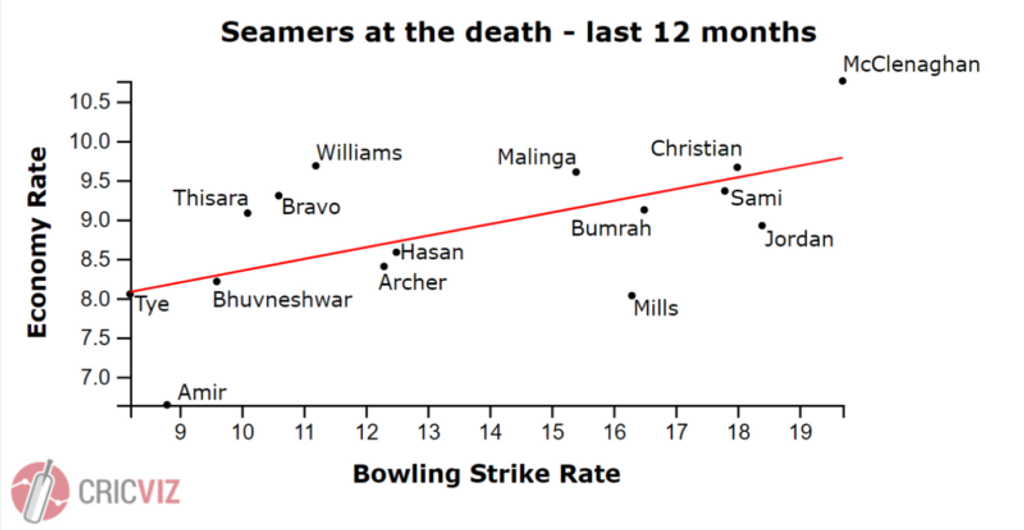

Well, it might have something to do with a statistical difference between the two bowler types in the final overs. The scatter graphs below show that in recent times, seam bowlers at the death are far easier to label either good, or bad, simply by looking at their basic statistical record. A good death seamer (e.g. Andrew Tye) is generally able to keep the runs down and take wickets; a poor one (e.g. Mitchell McClenaghan) can do neither.

This seems pretty logical, in some respects. Bowlers are almost always trying to take wickets whilst limiting runs, so it naturally it follows that good bowlers do both. However, this is not the case with spin. There seems to be more of a trade-off for spinners at the death; those who can take wickets in those frenetic final overs do so with a very high economy, whilst bowlers who can keep the runs down do so with a diminishing threat. Only the very best (e.g. Shadab Khan, Rashid Khan) can do both.

Perhaps this explains why they’re underused, relatively speaking. An effective pace bowler at the death is useful in a wider range of situations; Tye, Bhuveneshwar Kumar or Mohammad Amir can be used in either a tight finish where runs are all that matter, or when the bowling side is struggling and needs wickets. Contrastingly, whilst Ish Sodhi is an incredibly prolific wicket-taker at the death, and could be a great asset for Rajasthan Royals, bringing him on to bowl is a huge gamble given his economy. Equally, Narine and Mohammad Nabi may be able to limit the scoring rate, but they’re unlikely to be effective in breaking the game open when the required run-rate has dipped below 6rpo. Essentially, spinners at the death are tremendously effective in one situation, but tremendously ineffective in another.

The differences between spin and seam at the death place greater emphasis on the captain having the nous and intelligence to use the spinners correctly. Sunrisers skipper Kane Williamson can just throw Bhuveneshwar the ball in the last five overs, knowing that he’s capable of both taking a wicket and going for next-to-no runs. Strategically, it requires almost no consideration. But opting for Sodhi or Narine is a stark tactical choice, a clear decision to either attack or defend. In the cut-throat environment of franchise T20, the conservative choice holds considerable attraction for a nervous captain.

Finally, as a warning to T20 skippers reluctant to innovate – the benefit of moving towards spin at the death may not last long. As more spin is bowled at the death, it’s reasonable to assume batsmen will improve their record against the slower bowlers, simply through increased exposure. For the captain who rolls the dice this season – and you suspect it will be Williamson or Dinesh Karthik, given the tools they have at their disposal – the rewards could be far greater than the risk.