Sonali Dhulap examines the discrepancy of the performance between India’s and South Africa’s fast bowlers, the final signifier of the comprehensive dominance the hosts have enjoyed over the visitors.

In the summer of 2008, a South African side led by Graeme Smith set off for England, where they hadn’t won a Test series since 1965. Halfway through the first game of the four-match rubber, it looked likely the streak would continue. England declared on 593-8, South Africa were bowled out for just 247 and home skipper Michael Vaughan had no hesitation in asking the tourists to follow on.

The move backfired – 167 overs and three centuries later, South Africa had displayed all the characteristic grittiness that would eventually take them to a historic 2-1 series win.

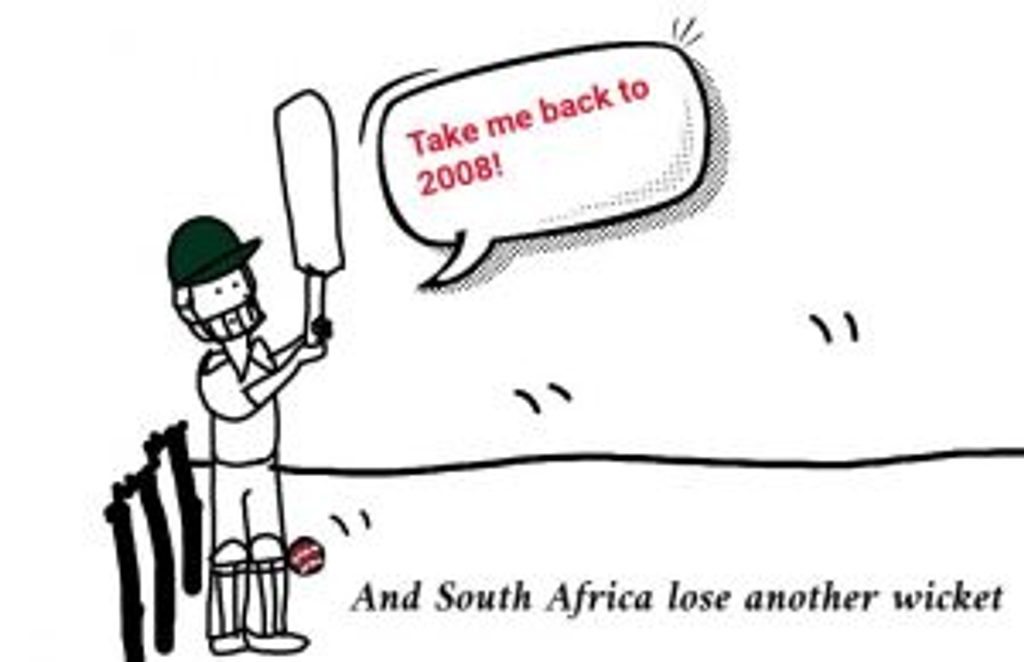

Flash forward to 2019, and, for the first time since that Lord’s Test, South Africa had been asked to follow on. This time, the result couldn’t have been any more different. They are no longer the side that went eight years without an away series defeat. Dale Steyn’s retirement marked the end of a generation of Test greats, few of whom have been adequately replaced. The team now finds itself suspended in limbo.

India have now won 11 consecutive home Test series. No other team has ever won as many.

They're quite good, aren't they?#INDvSA pic.twitter.com/alzbQMNH5D

— Wisden (@WisdenCricket) October 13, 2019

***

Before the second Test began, Faf du Plessis, the South Africa captain, had admitted that he would reconsider the team composition after their experiment to play three spinners in the first Test did not bear fruit.

India won the first Test in Visakhapatnam by 203 runs

India won the first Test in Visakhapatnam by 203 runs

With the 203-run defeat in Visakhapatnam fresh in the memory and the series on line, the visitors decided to tweak their bowling unit, bringing in Anrich Nortje to complete the fast bowling trio with Vernon Philander and Kagiso Rabada.

But a change in line-up brought no change in script. As was the case in the first Test, once India saw the first hour off on day one, they found it relatively easy to bat on the Pune surface. While Philander troubled the openers early on and restricted the flow of runs, his lack of express pace meant that the Indian batsmen had little to fear. Debutant Nortje had the raw pace to threaten but he leaked runs, unable to create any pressure. The real star of the pace line-up was Rabada, who used the movement and bounce the pitch had to offer to his advantage and snared the three wickets that fell on the first day.

A scoreline of 273-3 at stumps was as good as it got for South Africa however. India ended their first innings on a monumental 601-5, courtesy Virat Kohli’s career best 254*. The visiting quicks had returned combined figures of 81-14-259-3.

If there was any solace to be had, it was that the surface looked benign, and the Proteas might have felt they had simply come up against a surface they couldn’t exploit. India soon showed the folly of any such thinking.

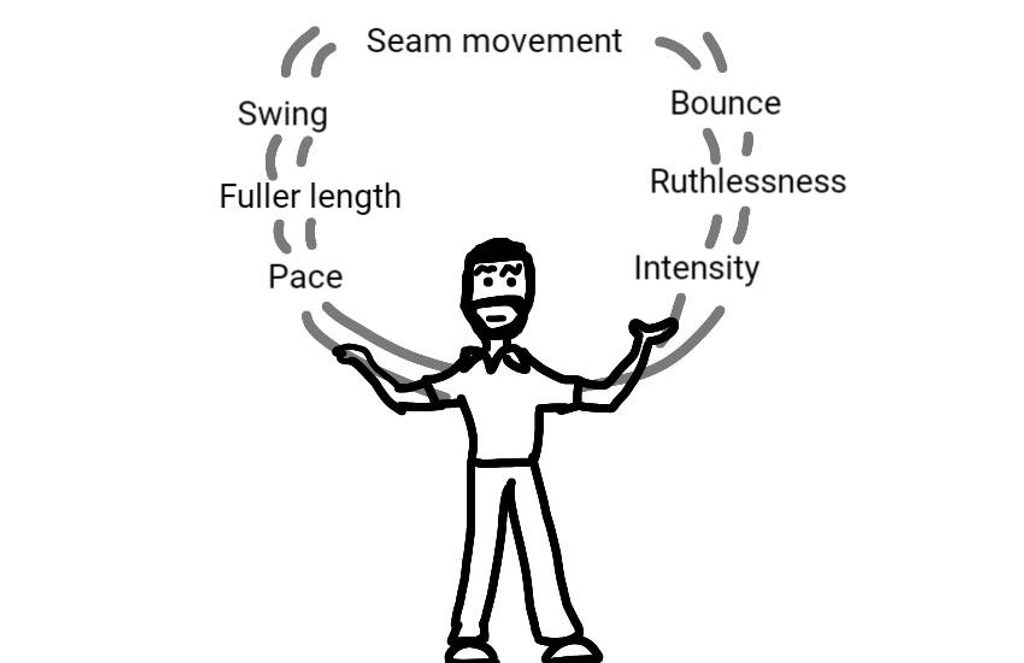

The current Indian seam attack knows how to juggle the different aspects of fast bowling quite effectively

The current Indian seam attack knows how to juggle the different aspects of fast bowling quite effectively

Though the constituent parts can change by the Test, India’s fast bowling unit rarely fails to resemble a well-oiled machine. This time it was Mohammed Shami with his skiddy pace, Umesh Yadav with his incisive swing and Ishant Sharma complementing the two as all three gears fit together to work in tandem.

“If the fast bowlers step onto the field, thinking the spinners are going to do all the job, it doesn’t do any justice to them playing in the XI,” said Virat Kohli after the game. “I think the attitude and the mindset they have created has been outstanding.

Shami on 🔥🔥🔥#INDvSA pic.twitter.com/nruaPwW1kt

— BCCI (@BCCI) October 6, 2019

“Even in India, they are looking to contribute. It’s not like if it’s hot and humid, they gave up. They ask for shorter spells and they give their 100 per cent. They have been brilliant. That’s when you see guys like Shami, Ishant, Bumrah and Umesh, in the past, doing important things that we want them to do.”

***

By the time, South Africa had lost half their side in the first innings, they only had 53 on the board. All five wickets had fallen to the Indian quicks – two to Shami, three to Umesh.

It was not just the pace of the Indian seamers, it was their relentlessness, quelling any sort of resistance. They bowled fuller lengths and rarely erred in their lines, giving batsmen no time to settle in. Even once they had, and even though the pitch had little to offer, Shami was able to extract extra bounce, forcing the South Africans to fend as the ball climbed onto their bats. Umesh used what movement there was well, bending the ball both ways and also straightening it off the pitch occasionally, weaving a web around the befuddled batsmen.

The difference in quality between the two sides couldn’t have been more apparent, and Temba Bavuma couldn’t find any other reason to explain the discrepancy in performance.

“The pitch was quite similar to what you get back in South Africa. I honestly found that it quite suited to our strength as a bowling unit. Probably being hypercritical, you would’ve expected our bowling attack and the skill we have to be able to make a lot more inroads,” he said after the third day’s play.

“Their bowlers have been able to put us under pressure. It’s quite obvious in batting totals that we’ve been able to accumulate. They are obviously doing something we are not doing. Or, their batters are just playing our bowlers better than our batters.” You can add to that the keeping too, with Wriddhiman Saha taking a trio of excellent second-innings catches.

It was not easy for the South African batsmen to square up against Indian seamers

It was not easy for the South African batsmen to square up against Indian seamers

The spinners remain as accomplished as ever, coming in to work their magic to wrap up South Africa’s lower half in both innings, but as long as the ball kept its shape and retained its shine, it was the quicks who used it to their advantage.

Once upon a time, not too long ago, it would have been unthinkable for an Indian fast bowling attack to dominate in this manner. And while recently we have become more accustomed to seeing their seamers excel – as R Ashwin said, “this seam attack of ours has completely earned the right of doing such things and we aren’t surprised about it anymore” – the contrast to South Africa’s struggles was still jarring. Here was an Indian bowling attack outplaying their opponents in their opponents’ preferred discipline, in conditions which should have offered little for them. What’s perhaps most frightening of all is that India’s quicks only seem to be getting better.