In 2015 Simon Lister, author of Fire in Babylon, explored the wider meaning of the West Indies’ period of dominance in international cricket.

First published in 2015

First published in 2015

My first cricket was England’s cricket. Simple and straightforward. From April to September I willingly sat in my father’s car as he drove the Saturday A-roads and Sunday B-roads of 1970s Shropshire. League matches at Wellington, Wem and Whitchurch. Friendlies at Shifnal and Sheriffhales.

Cricket seemed an easy, likeable game. Its history was convenient and digestible. English shepherds discovered it first, then men in top hats. There were great England players. Other countries started playing the game too, but never as well.

Then, in 1976, a very different journey with Dad. On the 133 bus in South London from Streatham to Oval station for a Test match. Hot sun, the smell of plastic cushions, washing-up-water beer and baking concrete. Noise, excitement. And black people. Black boys on the bus, black men in the next seats, black players on the pitch.

These were West Indians. One of them with the ball in his hand was a young fast bowler called Wayne Daniel. He was from Barbados.

Earlier this summer, nearly 40 years after that Oval Test, the BBC broadcast two programmes called Britain’s Forgotten Slave Owners. Using records from the national archive, the programme revealed the extensive number of ordinary people living in Britain who owned Caribbean slaves in the early 19th Century. One of the interviewees was Professor Hilary Beckles, the esteemed historian and cricket academic, some of whose thoughts were also recorded for my book, Fire in Babylon.

Beckles was asked about Barbados – the island of Wayne Daniel’s birth – in the days of slavery. This was a “militarised, highly capitalistic, entrepreneurial, brutal, terror-based society.” This beautiful island was unique, said Beckles, because Barbados was “the incubator where the greatest experiment in human terror in the modern era was first put in place.” That experiment was slavery. And the experimenters were the English. What was more, the threads of Caribbean cricket and those of colonial savagery were impossible to unknot.

I knew it not in 1976, but Daniel and his teammates were cricketers from a region with a very different history. Far less straightforward, not at all convenient.

It’s safe to assume that almost none of the young men who sat around me at The Oval that day were academics or historians. Many of these fans had been born in England and labelled by the government with the threatening and troublesome socio-historical tag ‘the coloured school-leaver’. They may not have studied in any detail the history of their region, but most watched cricket – and their players played cricket – with a purpose.

The year 1976 was a good time to be an urban British West Indian fan. You may have been misunderstood by your parents, ignored by your neighbour, dismissed by your teachers or employer, but for that summer and the 18 which followed, the power-play of the West Indian Test and one-day side brought great pleasure. For some, it was payback pleasure. Enough, at least, to make getting out of bed and going to school or work a little easier.

The alchemy of that power-play was simmered and served by one man – Clive Lloyd. Lloyd was the captain of the side who at the end of 1975 had overseen a humiliation in Australia. His men had their asses whipped by Lillee, Thomson and the Chappells. It would never happen again, Lloyd demanded change. What he craved was a formidable bowling attack. Four men that could be relied on to take 20 Test-match wickets in a working week.

It came to pass that those men were fast bowlers and the best of a large crop were Andy Roberts, Mikey Holding, Colin Croft, Joel Garner and then Malcolm Marshall.

The effect this team had on those who watched them was potent.

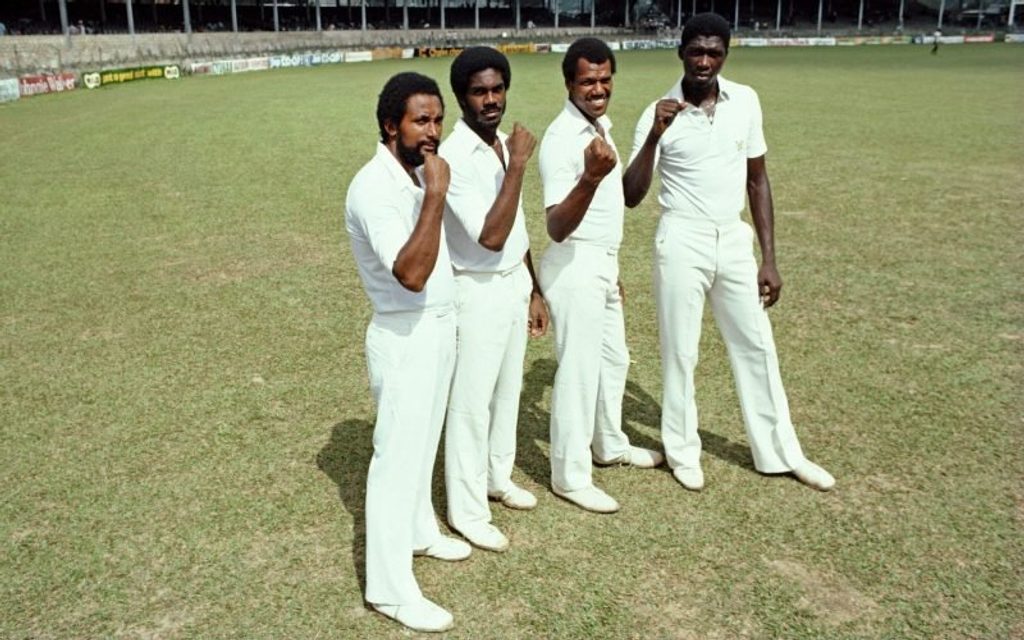

The four horsemen of the apocalypse: Roberts, Holding, Croft and Garner

The four horsemen of the apocalypse: Roberts, Holding, Croft and Garner

The broadcaster Trevor Phillips is one of the subjects of Fire in Babylon. As a student activist in London in the late ‘Seventies, he watched those bowlers (and the great batsmen of Lloyd, Richards and Greenidge) begin their modern domination of world cricket. It meant a lot.

Phillips was one of the young men who “felt the everyday experience of being black – the grating humiliations you suffered every day”. Yet the way this cricket team conducted themselves against their opponents was demanding of respect. “That translated into something very important for our generation because there were hardly any other black people you could point to and say ‘that’s the way to deal with it’. On the pitch they were anybody’s equal – and I suppose for young people it was quite simple; these guys didn’t take any shit from anybody.”

What Lloyd and his team did for the next 10 years, through one victory after another, was restore joy and respect to the region and the Caribbean diaspora. There was no West Indian nation to look back fondly on, no towering figures to admire. There was no Drake, no Shakespeare, no Nelson. Their collective birthing had been at a profound level both shameful and humiliating. Followed by an enduring disaster. West Indians wanted to run from their history, not savour it. But now, after 300 years, local heroes could be clearly pointed out. And they played cricket for a living.

It sounds simple, unremarkable even, that this group of cricketers began to play so well, but as Lloyd himself says: “When you consider our painful history, the bitter impositions forced upon those who came before us and the particular ordeals that the inhabitants of the Caribbean had to overcome each day of their lives, you can begin to understand why winning cricket matches for the West Indies meant so much to us all – those at home and those making their way around the world. Excellence had arrived. Our collective and individual skills had at last been recognised and could not be denied any longer. We represented people who could make a difference.”