Paul Edwards looks back to 1965, reminiscing Graeme Pollock, the South African all-time batting great whose scintillating century at Trent Bridge is regarded as one of Test cricket’s finest knocks.

Paul Edwards would like to thank David Wright and Alan Morton for their great help with the research for this article.

Nineteen-sixty-five. Monochrome. Three TV channels and an era in which you had to get out of your armchair to switch from one to another. At home in Southport this cricket-crazy little boy is watching Sportsview and they broadcast a feature on the South African tourists. Specifically, they focus on the fielding of Colin Bland. As I recall, they put a net up – at Canterbury, is it? – and ask him to throw at the stumps. I don’t remember him missing once but surely he must have done. Swoop, pick-up and an absurdly fast throw with no break between the movements, no sense of the fielder setting himself for the final action. Balance seemingly without effort. What was this?

Bland. “Lacking strong qualities and therefore uninteresting.” Has any cricketer had a less fitting surname? The South African was a gift to the cameras: his fielding had accounted for Ken Barrington and Jim Parks in the drawn first Test at Lord’s. Memories return, though they are hardly more than flickering frames of film, of batsmen stretching vainly towards the crease. Bland, said Leslie Smith in Wisden, had “barely more than one stump to aim at” when he ran out Barrington, that square-jawed epitome of English resistance.

In Playfair Cricket Monthly, Peter West, his photo byline enlivened by a pipe held contentedly in one hand, attempted an analysis of Bland’s fielding: “By dint of practice and hard work… he has lifted [his art] to quite a new plane… There is nothing in the remotest sense flashy about his performances.” If you said so, Peter, but in a decade of portly batsmen, wizened spinners and fast bowlers for whom fielding seemed a begrudged hazard, Bland’s athleticism was one of the most expansive shows in town, albeit that it was the product of months of practice. Suddenly, fielding was not merely that thing you did when it wasn’t your turn to bat or bowl. Swoop, pick-up, throw. Except that I missed by yards and/or fell over.

It had been a fairly bleak season. For the first time two international teams were touring but the New Zealanders won just three of their 19 first-class matches and were well beaten in the Tests. It had seemed vaguely appropriate that hot coffee was taken out to the players on the second day at Edgbaston. Summer more or less arrived with the South Africans and not solely because of Bland. Peter van der Merwe’s team contained a host of talented cricketers and they were to win the three-Test series 1-0.

Batting was a particular strength. “The most heartening feature of the tour was the willingness of these gay young men to hit the ball,” enthused Norman Preston in Wisden. And no one was more willing to strike the ball with phenomenal power than Robert Graeme Pollock. We saw that at Trent Bridge. Or if we were “watching” on television, we missed the best of it because BBC rarely showed the first hour’s play after lunch. That Thursday afternoon in 1965 live coverage of the Welsh National Eisteddfod was preferred.

Fifty years on and in an age clotted with hyperbole, people still talk of Pollock’s 125 on a seaming Nottingham wicket as one of the great innings. Cricket writers who were not born in 1965 speak of it with awed reverence, even though their only sight of the century is almost certainly the few yards of film used in a tribute to Pollock many years later. Those who were on the ground did not stint themselves. Jim Swanton wrote that Frank Woolley at his best would have been proud to play as well. John Woodcock observed that Pollock “held dominion where others foundered”.

Pollock made 125 of the 162 runs scored when he was at the wicket at a might impressive strike-rate of 86.2

Pollock made 125 of the 162 runs scored when he was at the wicket at a might impressive strike-rate of 86.2

***

David Wright had watched South Africa’s foundering with particular satisfaction. Then a 22-year-old umpire with Coventry and North Warwickshire CC, he had gone to Trent Bridge in the hope of seeing Tom Cartwright do well. It was a case of one Coventry Kid supporting another. Sitting on the Bridgford Road side of the ground, Wright watched Cartwright take three wickets in the first session. The tourists collapsed to 80-5 on a pitch described by Richie Benaud as “just like plasticine”.

Pollock had gone out to join Eddie Barlow with South Africa on 16-2 and he had made 34 in 68 minutes when the players came in for lunch. After the resumption, Pollock hit a further 91 runs in 71 minutes. In all, he made 125 of the 162 runs scored when he was at the wicket. His strike-rate on a pitch no one else could bat on was 86.2. He established a new yardstick by which greatness could be judged. “Above all, there was this scintillating innings by Pollock,” said Wright. “The timing was the thing. The ball just fizzed to the boundary and I thought, ‘My God the ball’s here already’. The batting was on a different planet when he was there.”

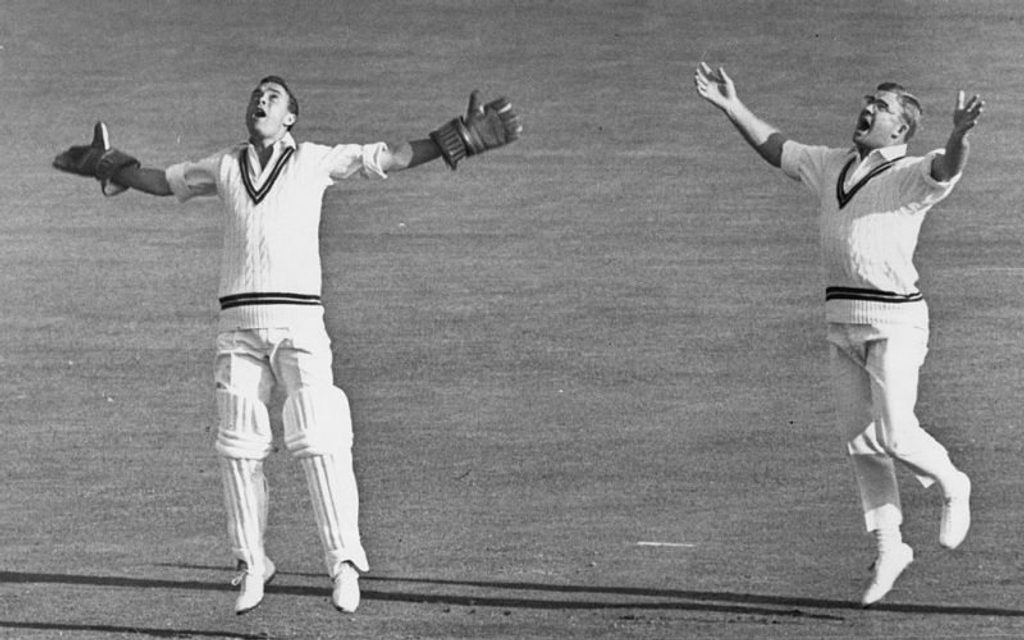

Denis Lindsay and Eddie Barlow celebrate the wicket of Bob Barber at Trent Bridge

Denis Lindsay and Eddie Barlow celebrate the wicket of Bob Barber at Trent Bridge

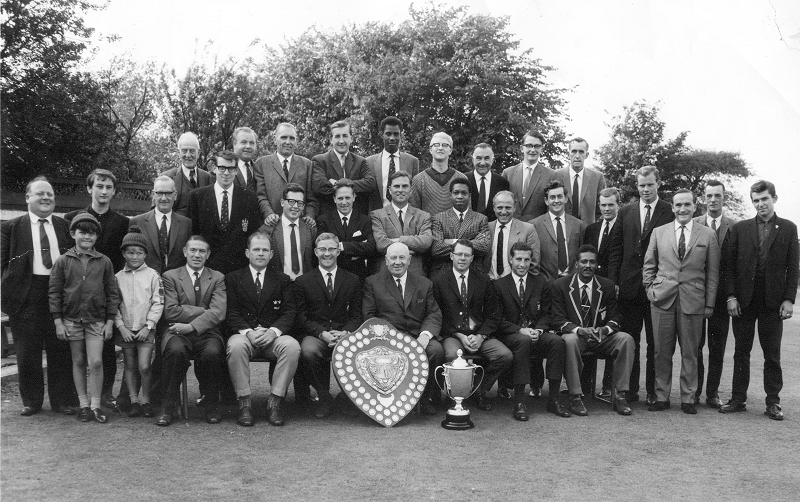

Then there is the photograph of 31 men. It was taken on Saturday, August 21 at Sandwell Park, the home of West Bromwich Dartmouth CC. Play on the first day of the South Africans’ match against Warwickshire had been abandoned that morning and a group of tourists had taken the chance to watch West Brom beat West Ham 3-0 at the Hawthorns. Then four South Africans made the short journey to the local club where the first and second teams were celebrating winning their championships in the Birmingham League, at that time the strongest league in England.

No doubt they were persuaded a little by the presence in the Dartmouth side of the former South African Test cricketer, Jon ‘Pom-Pom’ Fellows-Smith. Of the 31 adults in the photograph, 28 are wearing ties. One of the three non-conformists is still dressed stylishly, though, and he has a handsome half-smile playing around his lips as he looks into the lens. This is Jack Petit. He is a fitter at Tangye’s, a local engineering firm, although he looks more like a guitarist with the Dave Clark Five.

A picture featuring seven Test cricketers: Roly Jenkins is first on the left; then from left it’s Jon Fellows-Smith, Eddie Barlow, AN Other, Peter van der Merwe, Richard Dumbrill, and the West Indian Frank King; Jack Petit is standing on the extreme right; Peter Pollock is three to his right

A picture featuring seven Test cricketers: Roly Jenkins is first on the left; then from left it’s Jon Fellows-Smith, Eddie Barlow, AN Other, Peter van der Merwe, Richard Dumbrill, and the West Indian Frank King; Jack Petit is standing on the extreme right; Peter Pollock is three to his right

In all there are seven Test cricketers in the photograph: five South Africans, the leg-spinner Roly Jenkins, who was Dartmouth’s professional, and Frank King, who is proudly wearing his West Indian blazer. King is one of the three black cricketers in the picture. Nelson Mandela will remain in prison for another 25 years. When South Africa next tour England, he will be president of his country.

First published in 2016