There is something to be said for the thrill of an era when a player could take a hat-trick one day and score one the next, says Daisy Christodoulou.

This article first appeared in issue 14 of The Nightwatchman, the Wisden Cricket Quarterly

Buy the 2018 Collection (issues 21-24) now and save £5 when you use coupon code WCM9

Australia were 500 for 6 at The Oval in 1884, and nine players had already bowled for England, when the captain, Lord Harris, turned to his wicket-keeper, Alfred Lyttelton. WG Grace put on the gloves, and Lyttelton took 4 for 19 with his underarm bowling. But then, the multi-talented Lyttelton was used to excelling in different fields: by this stage he had already played in an FA Cup Final, become the first man to play for England at cricket and football, and gained Oxford Blues in cricket, football, real tennis, athletics and racquets. He managed all this before retiring from sport aged 28, in order to concentrate on his career in law and politics.

Still, for all his sporting success, he never captained England – unlike Tip Foster, born 21 years later in 1878. Foster remains the only man to have captained England at cricket and football, and still holds the record for the highest score by a Test debutant (287 at the SCG in 1903). Like Lyttelton, Foster’s sporting career was restricted by his career outside sport: he turned down many cricketing opportunities in order to focus on his business commitments.

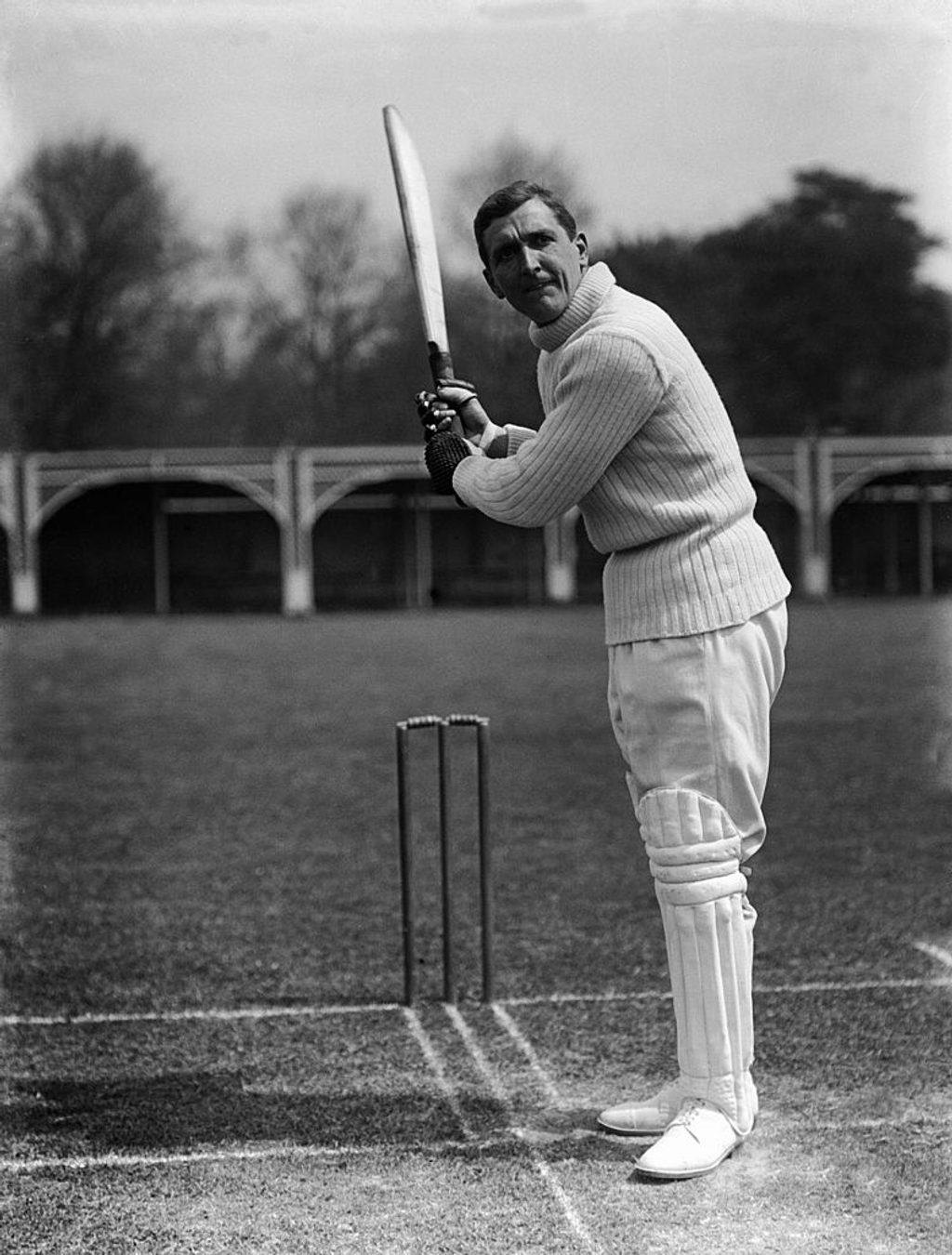

CB Fry – a useful all-round sportsman

CB Fry – a useful all-round sportsman

In a different way, Billy Gunn’s business commitments affected his sporting career. Employed in the warehouse of Richard Daft’s cricket equipment shop, he had to get up in the early hours to practise his batting. He too played for England at football and cricket, before retiring and setting up Gunn & Moore, the bat manufacturers. At Nottinghamshire, Gunn batted alongside Alfred Shaw and Arthur Shrewsbury, who organised the first British rugby tour of Australia. The captain on that tour was Andrew Stoddart, who also went on to captain England at cricket as well.

For all of these men’s versatile excellence, not one of them was offered the throne of Albania, as was famously reputed to have happened to CB Fry. But then, there are few sportsmen of any era who can hold a candle to Fry, with his triple Oxford Blue, long-jump world record, international football and cricket caps and FA Cup Final appearance. He probably would have won gold medals at the inaugural Olympic Games too – only nobody told him they were happening.

***

Up until about the 1960s, some exceptionally talented sportsmen were able to sustain careers in more than one sport and a handful of them managed to reach the highest level in two. Their numbers dwindled and eventually petered out entirely as the 20th century wore on and the commitments required by professional sports grew ever greater. As a result, their achievements will never be equalled and, from a modern perspective, are barely believable.

Fry’s career, in particular, is like a cross between something in a Boy’s Own Paper and a Monty Python sketch. As well as his astonishing feats of record-breaking athleticism, he also liked to perform his “party piece” of jumping from the ground onto a mantelpiece in one leap. Even though his phenomenal cricketing successes needed no exaggeration, he exaggerated them anyway, claiming hat-tricks and unbeaten captaincy records that he never actually achieved. And then there is the utterly bizarre offer of the throne of Albania, which may have been a real offer, may have been an elaborate practical joke by Fry’s Sussex colleague, Ranjitsinhji, or may have been an even more elaborate counter-bluff by Fry, playing along with the joke in order to embarrass Ranji. If it was all a joke, it must certainly qualify as one of the more imaginative dressing-room pranks in history, putting Joe Root’s Bob Willis mask into some perspective.

***

But it’s not just Fry. Amongst the men who played two or more sports to a high level, it feels as though the flamboyant, glamorous and even tragic are over-represented. Many of them were blessed with abundant talent and represented a compelling and attractive ideal of unstudied excellence. (It’s perhaps no surprise that two of the most romantic figures in cricket, Denis Compton and Keith Miller, for whom the Compton-Miller medal is named, both excelled at other sports.) As well as providing thrills and excitement, the histories of these dual sportsmen tell us something about how modern sport has developed, and the outsize impact cricket has had in that development.

The rise of the dual sportsman coincided with cricket’s first Golden Age, the quarter-century before the First World War. As well as being an era of great cricketing feats, it was also a time when there was an explosion of interest in sport, particularly the younger team sports of football and rugby, which had only recently been codified. Indeed, in the 1880s and 1890s, the various different football and rugby codes were often all referred to as “football”: Stoddart’s 1888 team were known in Australia as the English footballers, despite playing what we would now call rugby union. As late as 1892, football and rugby were evolving and learning from each other: in that year, the amateur Corinthians football team challenged the amateur Barbarians rugby team to a game of rugby – and won. The rugby historian OL Owen argued that “the success of the fast and powerful Corinthians, forwards as well as backs, led to the speeding up of rugby forward play.”

The histories of these dual sportsmen tell us something about how modern sport has developed, and the outsize impact cricket has had in that development

In this context, the more mature sport of cricket, whose rules had first been formulated by the MCC in 1788, offered something of a template. Shaw and Shrewsbury got their idea for a rugby tour of Australia from the cricket tours they had played on, while many of the big early football and rugby matches were played on cricket grounds. The first international football game was played at the West of Scotland cricket ground in Partick, while the first FA Cup Final was played at The Oval.

Both of these early football games owe a lot to the organisation skills of CW Alcock, one of the most important men in the early evolution of football and a perfect example of the fluid links between sports at this time. He was educated at Harrow, where he played football and cricket without very much distinction.

After leaving school, he went to work for his family’s business interests in the City of London, but he kept playing football and cricket, and kept organising football matches at a time when there was very little supporting infrastructure. He formed Wanderers FC, the best of the amateur football clubs, and recognised at the time as being the footballing equivalent of MCC. In 1870, he became secretary of the Football Association, and proposed the idea of a football challenge cup competition. Wanderers, captained by Alcock, were to win the first FA Cup in 1872, held at The Oval. Just a month before the final, he had become secretary of Surrey County Cricket Club too. He was to hold senior positions at Surrey and the FA for the next quarter-century, sometimes writing letters to himself as the representative of the two organisations, as well as arranging and playing in the first football internationals, refereeing two Cup finals, and organising the first Test match in England, in 1880 against Australia at The Oval. Alcock, however, was not a fan of all sports. He was critical of the growing popularity of lawn tennis, attributing it to an unmanly desire to want to spend time with females.

Cricket was not just the more mature sport at this time: it was also the most dominant and, as a result, most of the all-round sportsmen in this era had cricket in common. And whereas rugby and football competed for dominance in the winter months, cricket held sway in summer. Winter cricket tours and summer football ones are not quite as modern as we might think, but still cricket was generally not competing with other sports over the calendar. Some players managed to compete in all three team sports, but in general combining football and rugby was harder and rarer. There have been 12 English international cricketer-footballers, and seven cricketer-rugby players, but no international football-rugby players.

Between them, those three British team sports went on to conquer most of the globe and, to begin with, the links between the sports abroad were just as pervasive as those at home. For example, the Buenos Aires football club evolved out of the Buenos Aires cricket club; Charles Miller, who famously introduced football to Brazil when he took two footballs there in 1894, also played cricket for the Sao Paulo Athletics Club. Early football matches in Australia were played between cricket clubs, while in Italy, AC Milan and Genoa were first established as cricket and football clubs. Interestingly, however, those countries that embraced football rarely took cricket or rugby to their hearts. Those that adopted cricket sometimes took on rugby, but rarely football. Thus, whilst cricket, rugby and football all became international sports, the cricketer-footballer did not travel so well and remains a mostly British phenomenon.

Interestingly, those countries that embraced football rarely took cricket or rugby to their hearts

Professionalism increased after the First World War, but this did not immediately lead to the decline of the dual sportsman. Many of the dual sportsmen mentioned above were amateurs, but even the professionals played a game that would seem amateur to modern eyes. Even those who played for money often had a job or a trade as well, salaries were reduced or even non-existent in the off-season, and training, fitness regimes and tactical work were all in their infancy.

The simplest definition of professionalism – that of pay for play – arguably helped those who wanted to pursue a career in two sports. Denis Compton’s mother turned her nose up when she found out that he’d been offered a post on the groundstaff at Lord’s, because it would leave him without a job for eight months of the year. Then the job on the groundstaff at Arsenal came along. There were plenty of men playing two sports in the Middlesex, Arsenal, and England sides Compton played in: his older brother Leslie kept wicket when Denis bowled his chinamen, and mopped up at centre-half when he lost the ball on the outside left. Joe Hulme also represented the same two teams, and Patsy Hendren, whom Compton idolised, had been a successful footballer earlier in his career. In fact, in one of Compton’s first matches for Middlesex, he batted at No.3 with Hulme and Hendren at No.4 and 5, and their opponents Hampshire opened the batting with Johnny Arnold, a one-cap wonder in both cricket and football. Later on, in the 1953 Ashes series, Compton would play in the same cricket team as Willie Watson, two years his junior. Watson also played four matches for the England football team, and was selected for the 1950 World Cup, although he didn’t play a game. Watson’s maiden Test century, in the Lord’s Ashes Test in 1953, saved the match for England and made Compton’s series-winning runs at The Oval later that summer possible.

Denis Compton: Arsenal footballer and England cricketer

Denis Compton: Arsenal footballer and England cricketer

If before the Second World War professionalism might have helped the dual sportsman, by the time of Watson in the 1950s it was definitely a hindrance. Better pay may have helped players to sustain two sporting careers, but the pay was soon followed by other effects of professionalism, many of which affected amateurs just as much, and which made doubling up much harder. Longer seasons and more frequent tours abroad are often cited as consequences of professionalism that have led to the decline of the dual international. But there was probably never some golden age when the different sporting seasons fitted neatly into contiguous parts of the calendar.

Cricket tours were happening from the 19th century onwards, and summer football tours are not just an invention of rapacious 21st-century chairmen. The difference was that in the 19th and early-20th century, it was easier to pick and choose matches and tours, both domestically and internationally. England matches in all sports had a much more fluid cast of players, and much less of a “Team England” approach. Over time, more definite competition structures developed. Cups and one-off challenge matches declined in importance. Leagues and series assumed more importance, and required a more settled and stable team. This probably had more of an impact on the ability to play two sports at once than the regular seasons overlapping. After Compton played his first full season of Test cricket in the English summer of 1938, there was a tour that winter to South Africa. He turned down the chance of touring in order to play football for Arsenal, but failed to hold down a place in the Arsenal first team that season. Out in South Africa his contemporaries, Len Hutton and Bill Edrich, established themselves in the Test batting line-up and played in the famous Timeless Test at Durban in March 1939. But skipping the tour had no long-term consequences for Compton’s cricketing career. He was back in the team for the first Test against West Indies the following summer.

”I am rather doubtful about England’s wingers, Stan Matthews and Denis Compton. They are grand to watch but both are individualists”

Compton would have a strong case for being the greatest of all the dual internationals – if, that is, he actually were one. As well as his 78 cricket Tests, he played 12 times for the England football team, but in war internationals, which did not count as full matches. However, the standard in these matches was generally high, with Stanley Matthews often playing outside-right to Compton’s outside-left and the two frequently being compared, although not always in flattering terms. After one match, a commentator said: “I am rather doubtful about England’s wingers, Stan Matthews and Denis Compton. They are grand to watch but both are individualists.” If we include Compton’s war football matches, then his combined total of caps in both sports would be greater than the combined total of any of the other 19 dual internationals, despite the fact that he lost six of the best years of his career to the war.

After Willie Watson, Mike Smith played one rugby Test for England in 1956, as well as 50 cricket Tests over the following 16 years. Arthur Morris won his only football cap in 1951 and his last cricket cap in 1959. They are the last English dual internationals. But just after this, perhaps one of the greatest double acts of all occurred. In 1964, Jim Standen managed something that had eluded Fry, Compton, Lyttelton and all his illustrious forebears: he won the FA Cup and County Championship in the same year. Even more remarkably, he did so with West Ham and Worcestershire. Not only were these two teams over 150 miles apart, making travel between the two difficult, but they were two teams without the same tradition of success of, say, Compton’s Middlesex and Arsenal. In fact, for both West Ham and Worcestershire, the trophies they won in 1964 were the first major ones in their history, and in both cases, the wins started a golden era of success.

Standen also played a crucial role in each team’s victory. He was West Ham’s goalkeeper when they beat Preston 3-2 at Wembley, in a team that included Bobby Moore and Geoff Hurst. He also led Worcestershire’s bowling averages, taking 64 wickets at an average of 13. It’s a remarkable feat, and it’s puzzling as to why it isn’t better known or talked about. Standen himself was part of a West Ham team with cricketing influences: Hurst and Moore apparently first met whilst playing cricket for Essex Schools, and Hurst himself played one first-class match for Essex, scoring 0 and 0 not out. It took the England cricket team until 2010 to win a World Cup, but two English cricketers managed it 44 years earlier.

Since Standen’s feat, fewer and fewer sportsmen have even played two sports to a high level, let alone won trophies in both. Instead, the story now is of sportsmen who played more than one sport to a high level in their teens, and then concentrated on one. The Neville brothers were both talented cricketers, and Phil Neville was an opening batsman who captained England under-15s. In an interview with Sky last summer, Gary Neville maintained that, had the brothers both gone on to play cricket, he would have been a better cricketer than Phil even though Phil was much better aged 15 “because Phil was a better footballer aged 15 too.”

Gary Neville maintained that, had the brothers both gone on to play cricket, he would have been a better cricketer than Phil even though Phil was much better aged 15

The links between football and cricket positions are not as straightforward as might be assumed: one might have expected the goalkeeper Standen to be a wicket-keeper, not the striker Hurst. But the links are perhaps close enough to allow some tantalising suggestions. Would Joe Hart have been a barnstorming and uncomplicated all-rounder in the Ben Stokes mould, and might Ian Bell have been a Stewart Downing-esque winger, constantly flattering to deceive? Steve Harmison is now the manager of Ashington FC in the Northern League. Unsurprisingly, he says that he is not the type to throw teacups around the dressing-room.

In women’s sport, as recently as the 1990s Clare Taylor played as a central defender for the England football team and an opening bowler with the England cricket team. In 1993, she played in the FA League Cup Final with Knowsley at Wembley, and then won the World Cup Final at Lord’s with the England cricket team. She also held down a job with Royal Mail, although she did concede that she spent a lot of time away on unpaid leave. Few of the male dual internationals mentioned above can have made as many sacrifices for their sporting careers and have received so little public notice. When I first started playing football for a local girls’ club, aged about 10, I can remember reading a tiny, throwaway newspaper snippet about Taylor and longing to find out more about her exploits. Even then, when women’s football and cricket were much less developed than now, it felt astonishing that such an impressive achievement was not better known and more celebrated.

One can romanticise the dual international too much. In general, the greater professionalism that prevents the dual international has led to more consistently high standards across most sports, and to players being rewarded with the wealth created by their hard work and talent. And whilst the dual sportsmen thrilled the sporting public, when their careers ended many of them struggled to cope. In The Great Gatsby, F Scott Fitzgerald describes the American footballer Tom Buchanan as “one of those men who reach such an acute limited excellence at 21 that everything afterward savours of anti-climax.” It is an apt line for many great sportsman, and more so for some of these dual internationals, even if some of their excellence felt unlimited.

Compton’s biographer says that life could hardly fail to be an anti-climax after such a dramatic career, while his son rather wistfully informs us that he felt as though his father belonged to the nation, not to his family. CB Fry suffered with mental-health problems and perhaps never came to terms with the fact that his career in politics and journalism was not as successful as that in sport. Stoddart and Shrewsbury both killed themselves, Stoddart after his career was over and Shrewsbury as his was coming to an end. Perhaps in some ways the demise of the dual sportsman is a good thing, as it forces even the most talented players into following the routines and the practices of the team, and to recognise a limit to talent. Still, there is something to be said for the thrill of an era when a player could take a hat-trick one day and score one the next, and when the impossible dreams of childhood were made possible by a lucky few.