It’s been over a year since Liam Plunkett last represented England, and the ODI world champions have still not successfully replaced the middle-overs expert. CricViz analyst Ben Jones takes a look at the options on offer.

Ask an England fan to name their 2019 World Cup final heroes and there are some names you anticipate hearing. Ben Stokes, a given; Jofra Archer, the super over hero; Jos Buttler, for once the hipster’s choice. One man who might not crop up is Liam Plunkett. The man who took 3-42 on that dramatic day at Lord’s – dismissing Kane Williamson, Henry Nicholls, and Jimmy Neesham – is often overlooked when rattling off the iconic names who lifted the trophy.

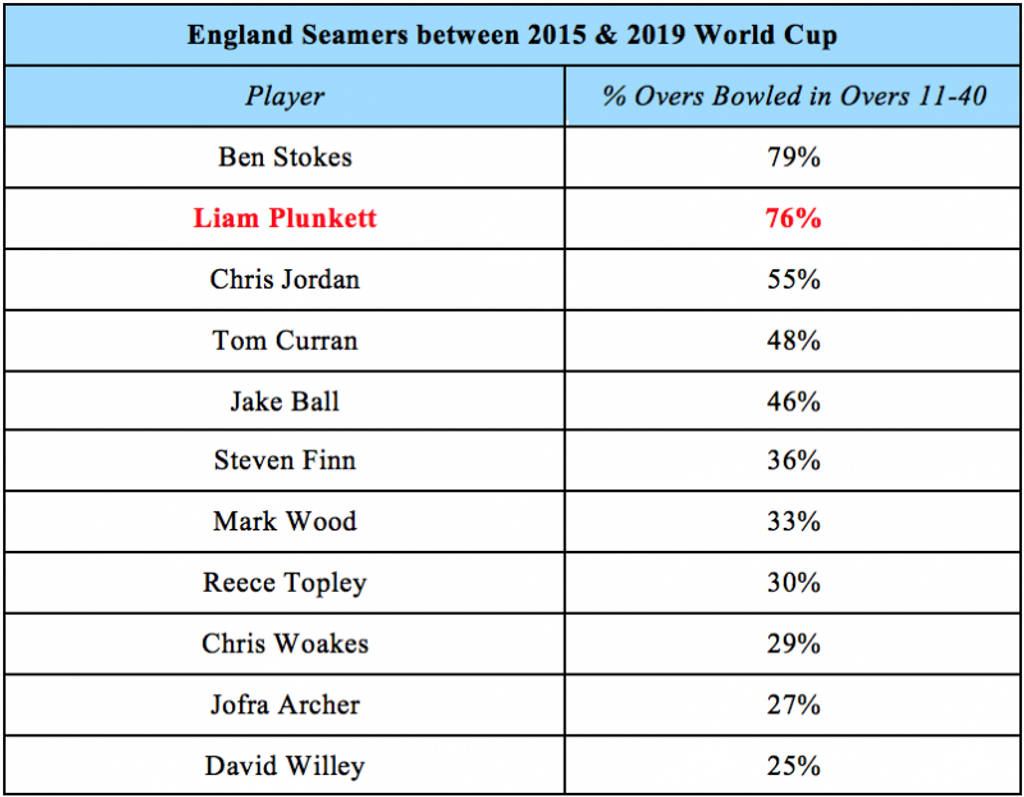

And yet to those within the England set-up, Plunkett was among the most important members of that side. The main reason for this was that England used Plunkett in a very specific role. Between World Cups, England had 11 seamers bowl a considerable number of balls in the middle overs; of those bowlers, only Ben Stokes delivered a higher proportion of his total deliveries in the middle overs than Plunkett. There’s a reason why ‘LIAM PLUNKETT IN THE MIDDLE OVERS’ was a Twitter meme throughout the tournament – that’s where he excelled.

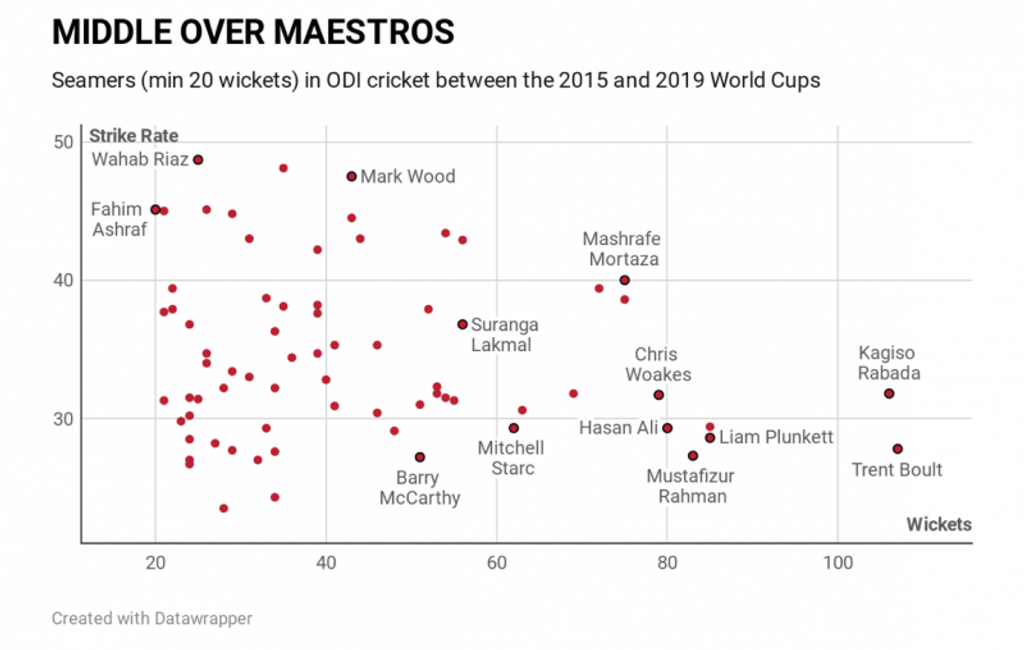

They identified a talent early, they gave him time and backing to learn the role and then reaped the rewards. In the last World Cup cycle, only two seamers took more middle-over wickets than Plunkett – Trent Boult and Kagiso Rabada – and only one did so with a better strike rate than the Englishman.

This is not to say that Plunkett should be in the side. His World Cup final performance was excellent, but that should not obscure the fact that there were clear signs of decline. There were concerns in the set-up about his loss of pace in the run up to the tournament, and while it is testament to his skill and experience that he still contributed, there’s no question that his physical attributes are no longer what they were.

There have been arguments made that Plunkett should have been kept around to teach the next generation the tricks of the trade, but once you reach that point, the employment of bowling coaches comes into question. If the only way you can teach a horse to be a racehorse is to get another racehorse to talk them through it, then what’s the point of a jockey.

The idea that Plunkett had earned a testimonial, a run-off into retirement and a sepia sunset, is entirely at odds with the selection logic which made him a success. World Cups don’t last six weeks; they last four years. Eating into that time with sentimentality is folly.

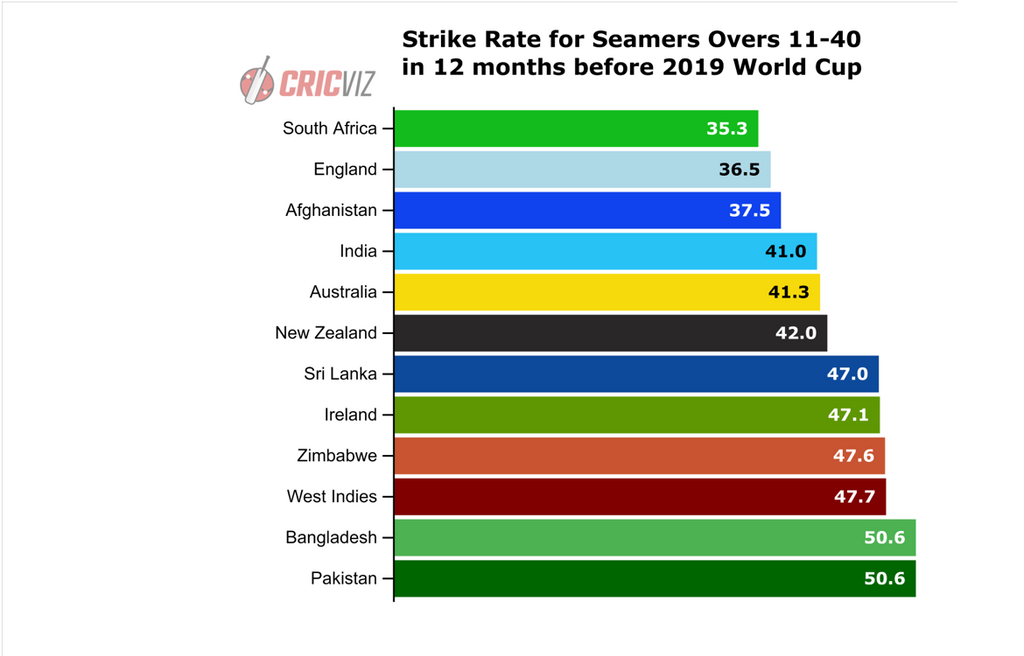

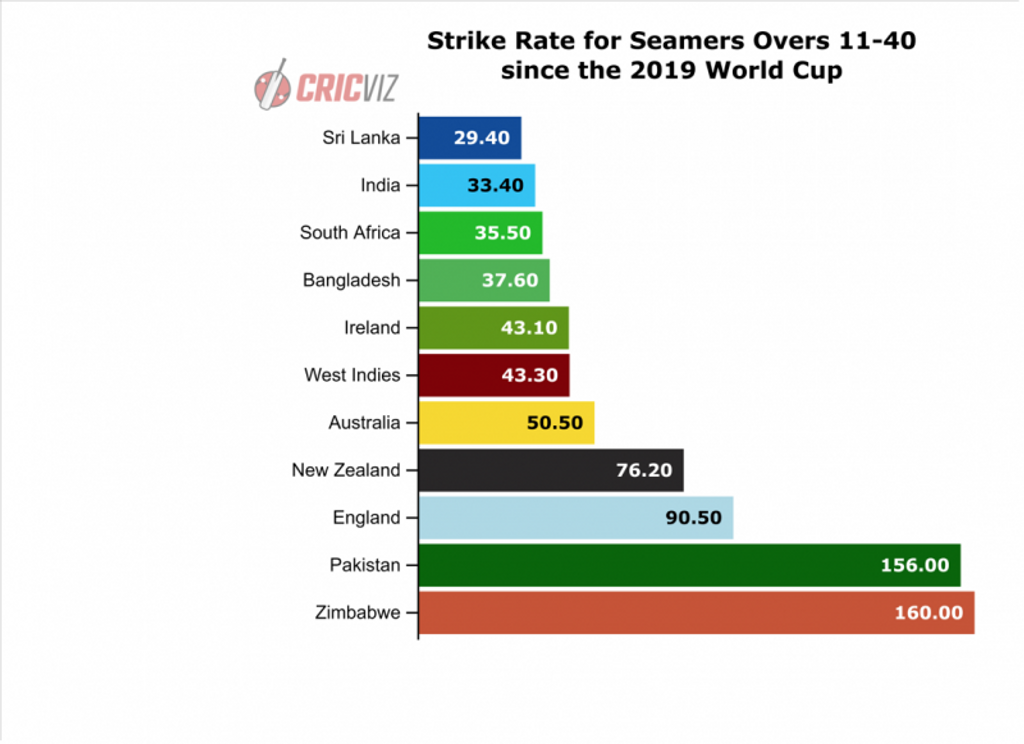

It’s that logic which dictates how England need to move swiftly to identify Plunkett’s successor because right now, his absence is all too notable. In the 12 months before the World Cup, England’s seamer strike rate in the middle overs was the second-best in the world, and Plunkett was a significant part of that; since that World Cup final, England’s seamers have been the third-worst in the world at taking wickets in the middle overs.

The third ODI against Ireland was something of an aberration, a significantly weakened England attack taken apart by a destructive, experienced hitter. Paul Stirling hit 101 not out (91 in the middle overs, with Tom Curran the only seamer able to keep him under a run a ball. Andrew Balbirnie hit 92 not out (90) alongside him, as England went nearly 33 overs without taking a wicket and Ireland landed a remarkable win over the world champions. While there were significant extenuating factors, there is a sense that this is a weakness in England’s set-up, right now.

The most natural successor to Plunkett was unavailable for that Ireland defeat, away with the Test squad – though not playing very much. Mark Wood seems well suited to performing the Plunkett-role with similar success. There’s no question Wood has the pace to trouble well-set batsmen, given that since the start of 2018 only Mitchell Starc and Lockie Ferguson have been quicker in ODI cricket, of those to play at least 10 matches. Wood’s middle-overs strike rate in ODIs (39.6) is only slightly worse than Plunkett’s since the 2015 World Cup (38.0), so there’s evidence that Wood already has good work under his belt. Already in the team, already with a World Cup winners’ medal in his back pocket, Wood is the obvious choice.

However, as is always the case with Wood, fitness and long-term reliability are not a given. The Durham seamer is only 30, but he’s struggled throughout his career to string together back-to-back performances, and has regularly been out for very long stretches. England may feel that with developing a younger bowler alongside Wood, to do a similar role, would be sensible.

As such, the progression of Saqib Mahmood is key. A rare young English bowler capable of bowling quickly and (according to observers who follow him closely) reverse swinging the ball, Mahmood is a bowler England want to invest in, but they may need to be patient. Whereas Wood is, to use the phrase of the moment, an ‘oven-ready’ ODI bowler in those middle overs, Mahmood’s record is mixed. He’s taken just seven List A wickets in overs 11-40, at an average of 73.16, and while Mahmood shouldn’t be judged too harshly on a small sample in his secondary role (for Lancashire, it is his new-ball exploits that have attracted attention), it’s a concern that England might be throwing him in at the deep end, learning new skills at the very top level.

If England want to stick with a seamer as the main partnership breaker in the middle, alongside Adil Rashid, then those are probably England’s best two options.

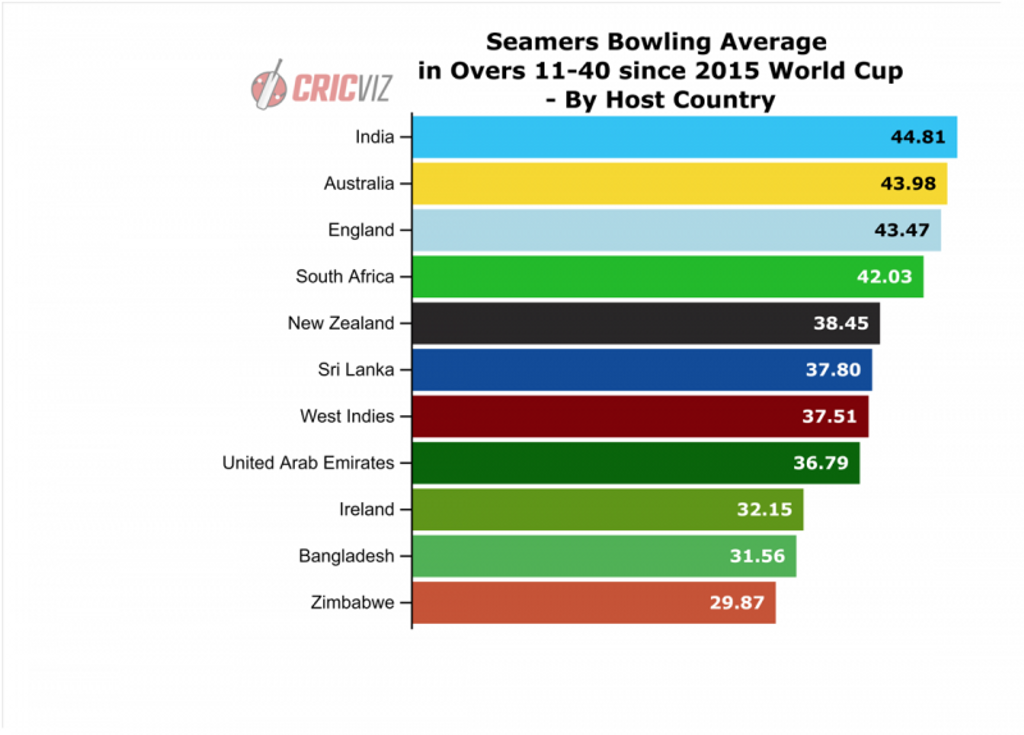

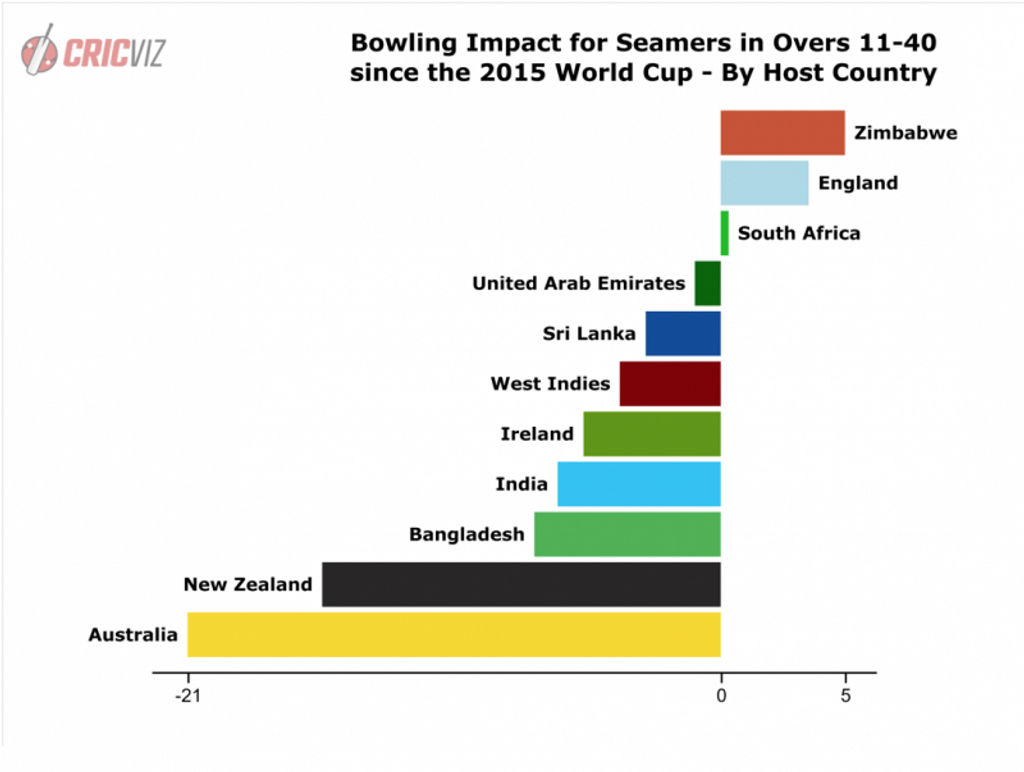

However, the next 50-over World Cup is in India where, comparatively, seamers have struggled to take wickets in the middle. The bowling average for quicks in India since the 2015 World Cup, for those middle overs, is 44.81; that’s the highest in the world, the worst for any country. The need for a Plunkett-style bowler might be less than on the typically hard, true, flat wickets in England.

Yet by that measure, England is the third-worst place to bowl for ODI seamers in the middle. That’s probably partly true, given the outrageous scoring rates we have seen in England over the last few years, but the effect that those seamers can have, if they get it right, has been huge. We can see this in more intelligent data – the Bowling Impact of seamers in the middle is much, much better in England than in India. The temptation to move away from pace in the middle, and towards more spin, must be significant.

If England did move in that direction, their spin reserves are a little bare, but not without talent. They would likely have to gamble on Adil Rashid still being fit and firing in three years time, by which time he’ll be 35 – with his history of shoulder problems, it’s no guaranteed thing. Moeen Ali, even disregarding his loss of form with the ball, would be 36. Blooding youngsters to come through and succeed, or challenge, the established spin-twins seems prudent.

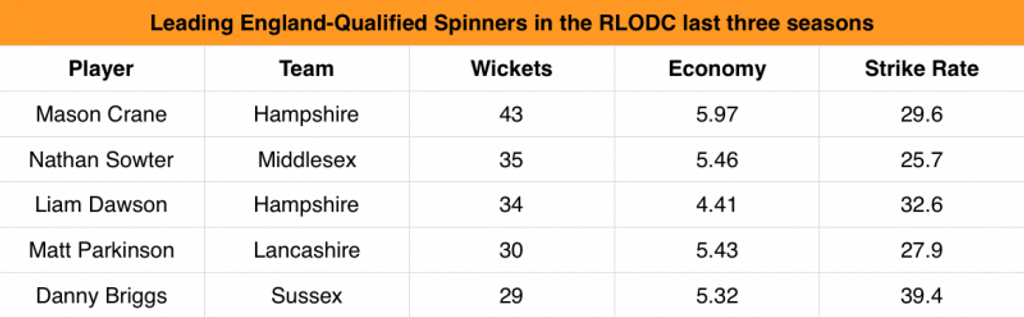

In the last three seasons of the Royal London One-Day Cup, the leading English spinner (in terms of wickets alone) is Mason Crane. The Hampshire leg-spinner has taken 43 wickets in 24 games, going at 5.97 runs an over but picking up a wicket every 29.7 balls; an aggressive, expensive, but very impressive option. What is particularly pleasing from an England perspective is that 32 of those wickets have come in the middle overs. The other obvious wrist-spin option is Matt Parkinson, a slower and more traditional leg-break bowler, who England have seemed keener to blood into international cricket than Crane; the Middlesex spinner Nathan Sowter, only recently qualified and thus under-explored in the development squads, also has a record to challenge the others.

All in all, England will feel like they have a wide enough range of candidates to replace Liam Plunkett and to fill his role in the side. The hard yards put in during the last World Cup cycle, identifying and developing talent in both the top six and in the bowling attack, have afforded England the luxury of being able to focus quite intently on this role – the rest of the side broadly picks itself, when everyone is at full fitness. Whoever is picked and backed will largely be picking up the baton from Chris Woakes after some early wickets, be working alongside Adil Rashid at the peak of his powers in the middle, and know that they have the safety net of Jofra Archer’s death bowling to come when their spell is finished. It’s always easier to tweak a winning side than a losing one. Hopefully, England take advantage of their own good work.