150 years on from the 1868 Australian Aboriginal cricket tour of the UK, Olly Ricketts looks back on the life and times of the team’s hero, Dick-a-Dick.

The Royal Albert Memorial Museum in Exeter is lending Aboriginal artefacts, newly identified from the 1868 tour, for display at Lord’s throughout the 2018 season. To visit the MCC Museum book a Lord’s tour at www.tour.lords.org. Alternatively, entry is free to the museum on all major match days to people attending matches

This article first appeared in The Nightwatchman, the Wisden Cricket Quarterly

Buy the 2018 Collection (issues 21-24) now and save £5 when you use coupon code WCM7

On June 13, 1868, Dick-a-Dick was carried from the Lord’s pitch into the dressing rooms on the shoulders of a throng of spectators who had adopted him as their new hero. He had scored a grand total of eight runs – which was admittedly better than his tour average of 5.26 – and had not taken a single wicket or catch. Not many cricketers have managed to provoke such a reaction from the usually placid Lord’s crowd, let alone one who evidently wasn’t actually very good at cricket. But then not many people have lived a life so full of incident for such an event to seem like just another day.

Though records are sketchy of births and deaths in the Australian Aboriginal communities of the 19th century, it is believed that Dick-a-Dick was born at some point between 1845 and 1850 in Victoria. What is certain is that in August 1864 he played a central role in an incident which was to become part of Australian and indeed British folklore. On Friday August 14, 1864 three young siblings – Isaac (9), Jane (7) and Frank Duff (3) – went missing in the harsh terrain of The Wimmera, a region in western Victoria. Search parties proved unable to locate the children, not helped by torrential rain which had seemingly removed any evidence of where the Duffs might have gone. As a last resort, their father enlisted the help of three Aboriginal trackers, one of whom was Dick-a-Dick.

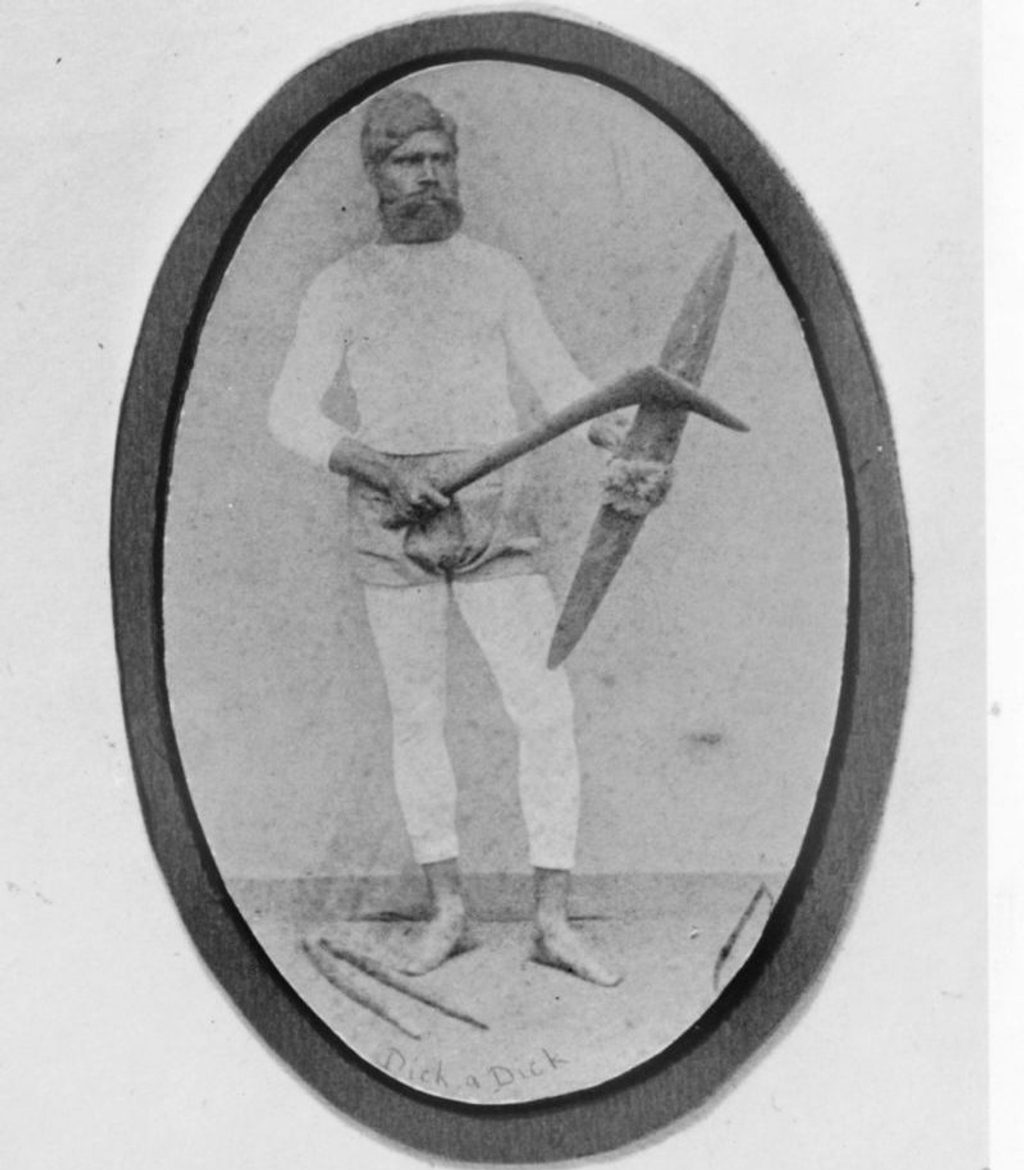

A drawing of Dick-a-Dick with a parrying shield and a leangle

A drawing of Dick-a-Dick with a parrying shield and a leangle

They began what seemed certain to be a futile search in the early hours of Saturday August 22, over a week since the children’s disappearance. Where others had seen only muddy paths and desolate ground, however, the Aborigines saw vital clues in tiny deviations and splintered twigs which led them to a clearing in which the Duff children must have spent their first night.

Later that day, the trackers found the children. Miraculously they were alive and well, though it seems unlikely they would have survived a further night of the freezing cold.

Dick-a-Dick and the other trackers did supposedly receive some remuneration for their efforts. However, they were largely airbrushed out of the reports in the local papers, which instead chose to focus on the selfless efforts of Jane Duff to keep her brothers alive (in spite of the cold she had given some of her clothes to Frank in an attempt to keep him warm), and their father’s role in the search. Many pictures of the scene omit the trackers entirely, showing the children being rescued by white men.

Two years later the story of the Duff children was turned into The Australian Babes in the Wood, an illustrated rhyme book for British schools. The trackers feature more prominently in both the narrative and the illustrations, albeit with Duff senior giving the orders:

“Ah, ’twas a joy to see that man

Returning with his new-found guides,

Dick, Jerry, Fred – three blacks to scan

The hidden path. – God aye provides!”

Four years later, another extraordinary chapter was to unfold in Dick-a-Dick’s story. During the 1860s, some Aborigines had begun playing cricket in the missions and on the sheep stations. Jane Lydon argues in Fantastic Dreaming: The Archaeology of an Aboriginal Mission that the missions “were intended to be environments in which the twin goals of conversion and ‘civilisation’ could be pursued”. Cricket, with its strong reliance on fair play and sense of hierarchy, could be used as a valuable teaching tool in the ways of the English.

While he had offered little with bat or ball, Dick-a-Dick had his own segment following the match in which Surrey players and officials were given the opportunity to pay a shilling and, from no more than 10 paces, throw a cricket ball at him

Moreover, many Aborigines seemed to have a natural aptitude for the game, for they were quick, agile and strong. It did not take long for speculators to realise that there was potential profit from the novelty of an Aboriginal cricket team. An attempted tour of Australia in 1867, (which was intended to go on to the UK,) in 1867 had proven to be a disaster both financially and personally, with four players dying either on the tour or shortly afterwards. By rights, there should have been a fifth. Dick-a-Dick was part of the squad, but had contracted measles, a devastating illness for the Aboriginal communities which had not been exposed to it until the European invasion and had therefore not built up a resistance to it. He was extremely fortunate to survive.

A year later, however, a second tour was proposed. The side was to be coached and captained by Charles Lawrence, an English ex-pat and former first- class cricketer. They were also accompanied by William Hayman, George Smith and George Graham as team managers and investors. Of course, for “investors”, read “profiteers”.

While it can be argued that Lawrence genuinely enjoyed coaching the Aboriginal players, of far more importance was the novelty factor involved with bringing such a side to both Australian and English audiences. It was common practice at the time for cricket matches to feature an extra day of “sports” after the main action had finished, usually comprising of running, jumping and throwing events. Lawrence et al saw a lucrative expansion of these events to include Aboriginal tribal practices adapted for white audiences. As such, they were not unduly concerned by the fact that many of their squad, including Dick-a-Dick, were not proficient cricketers, for their true value lay elsewhere.

***

On May 13, 1868 a team of 13 Aboriginal players, including Dick-a-Dick, arrived at Gravesend following a three-month journey by sea. In doing so, they became the first Australian cricket side to tour the UK. It is important to note that Dick-a-Dick’s birth name is actually Jumgumjenanuke. Aborigines were often given sobriquets by their pastoral landlords, who evidently struggled (to be bothered to learn how) to pronounce their real names. The players were therefore given exotic but often downright condescending nicknames. Unaarrimin became Johnny Mullagh, Bullchanach became Bullocky, and Arrahmunyarrimun became, erm, Peter. Evidently the well of inspiration had run somewhat dry by that point.

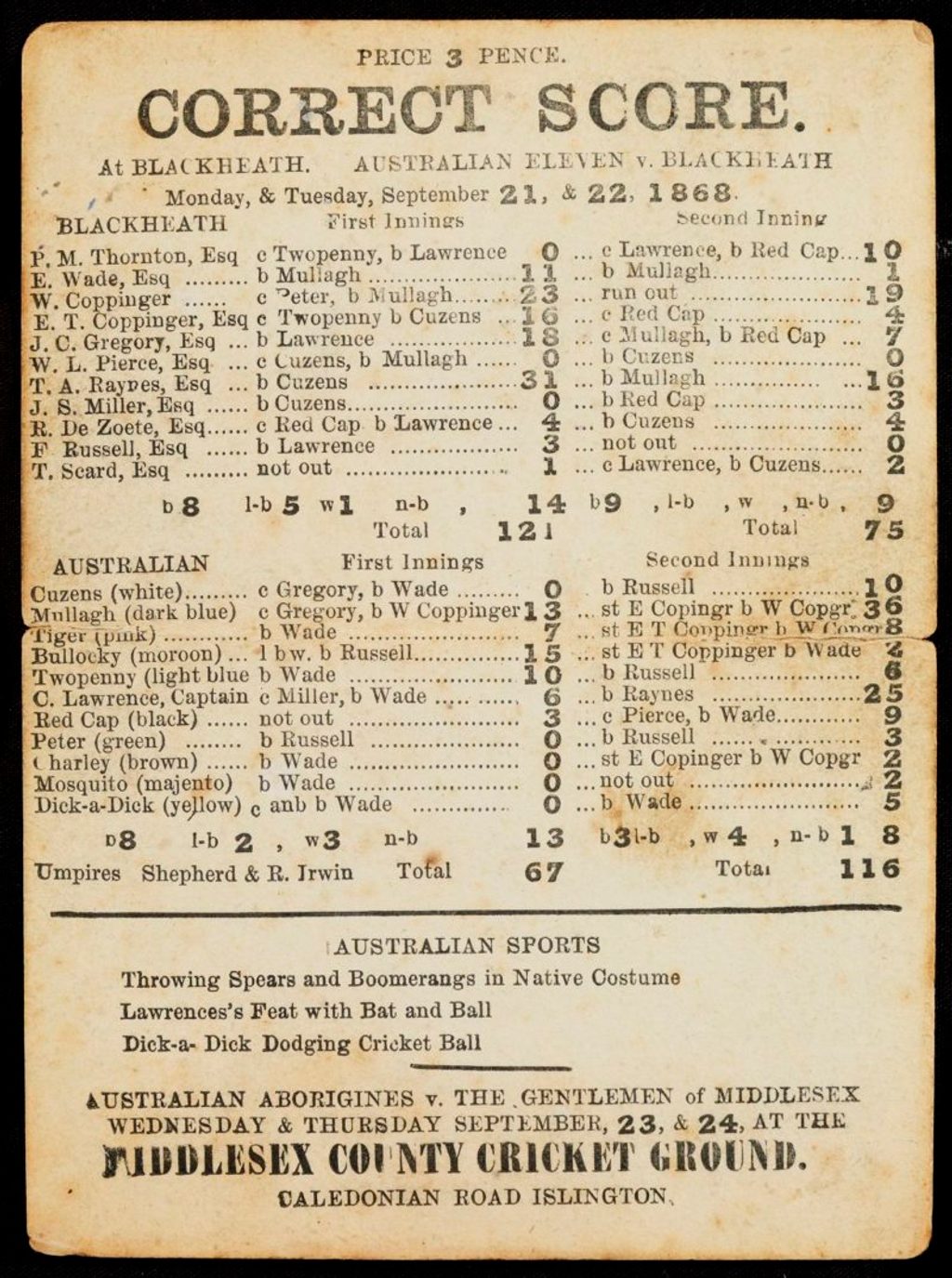

A scorecard from the Aborigines tour to England in 1868

A scorecard from the Aborigines tour to England in 1868

The tour began in a flurry of publicity on May 25, 1868 with a match against a Surrey side at The Oval. The press varied from the hyperbolic, with the Sheffield Telegraph describing the tour as “decidedly the event of the century”, to the Daily Telegraph’s more disdainful observation that “nothing of interest comes from Australia except gold nuggets and black cricketers”.

While he had offered little with bat or ball, Dick-a-Dick had his own segment following the match, in which Surrey players and officials were given the opportunity to pay a shilling and, from a distance of no more than 10 paces, throw a cricket ball at him. Really hard. Armed with just a parrying shield and leangle (a type of boomerang), Dick-a-Dick managed to avoid or deflect every single one, even when as many as seven were launched at him in unison.

Dick-a-Dick’s talents were not limited to dodging, however. He was an important part of the side’s mock hunts. He usually won the competition to throw the cricket ball as far as possible, and was an expert proponent of the 100 yards run backwards

The majority of the crowd were enthralled by what they had witnessed but some were affronted by the sight of a black man hollering with delight as he repeatedly humiliated the white man. Or so a few morons saw it, anyway, throwing abuse and indeed missiles at Dick-a-Dick until the police arrived to disperse the trouble. Thinking that throwing a bottle from 50 yards would prove effective when the source of their ire was his ability to avoid cricket balls from markedly shorter distances probably provides an insight into the intellect of the troublemakers. Regardless, a star of the tour was born.

Dick-a-Dick played in 45 of the 47 matches that the tourists crammed into their hectic five- month schedule in the UK. He was a strong, athletic man, but apart from the odd spectacular piece of fielding –- The Sheffield Telegraph acclaimed a “splendid” one- handed leaping dismissal, for example – his cricketing ability was truly average. The man himself cared little, as his turn as the ‘Artful Dodger’ (a moniker coined by the Australian ex-Test cricketer Ashley Mallett in his exceptional book Lords’ Dreaming about the 1868 tour) continued to prove a huge attraction for crowds throughout the country.

Dick-a-Dick’s talents were not limited to dodging, however. He excelled at several of the other events staged following matches. He was an important part of the side’s mock hunts. He usually won the competition to throw the cricket ball as far as possible, and was an expert proponent of the 100 yards run backwards, an event that I think we can all agree the International Olympic Committee IOC should strongly consider for inclusion in future Olympic Games.

Much of Dick-a-Dick’s appeal lay in his easy-going demeanour and keen sense of spectacle. Rex Harcourt and John Mulvaney argue in Cricket Walkabout that: “Dick-a-Dick was a showman of whom Barnum would be envious. It was not only what he achieved in the centre, but the manner in which he performed which delighted the crowds.” On one occasion Dick-a-Dick drew spontaneous applause from the crowd during a match in Bootle, simply by smiling at an inquisitive child who had come on to the pitch to stare at him while he fielded at long-leg.

Aboriginal artefacts, newly identified from the 1868 tour, on loan to MCC from The Royal Albert Memorial Museum

Aboriginal artefacts, newly identified from the 1868 tour, on loan to MCC from The Royal Albert Memorial Museum

While many of his team-mates found England to be a cold, lonely place, Dick-a-Dick fully embraced the life of the tourist. He had cash to spend, as he was the only Aboriginal making money from the tour. The 1868 tour ledger shows that the players were paid nothing more than cursory expenses; so popular was Dick-a-Dick’s dodging segment proving, however, that as well as making money directly from those who challenged him, later entries in the ledger show expenses listed as ‘Dickdodging’.

Dick-a-Dick was sober throughout the tour, and indeed appeared to disapprove of those team mates that did indulge, but he had his own vice: shiny crap. He spent a fortune on cheap tat, getting ripped off buying vulgar rings and watches wherever he went, and was never able to resist the lure of a fun fair. He also fancied himself as something of an art collector. One piece, an oil painting of an old woman, was so vile that the team’s management felt it necessary to devise an unnecessarily complicated plan to rid itself of it via a raffle. This plan almost came unstuck when Dick-a-Dick was one of three people to claim a winning ticket, but thankfully a generous (and perhaps blind?) soul offered Dick-a-Dick money for his ticket, and crisis was averted.

In the first 30 matches of the tour, Dick-a-Dick managed to avoid being hit by a single cricket ball. In the 31st first, however, his luck ran out. He had already had a shocking match even by his modest standards, failing to score in either innings. Given that he didn’t seem to care all that much for cricket, far worse was to follow during his post-match dodging display. Soon to be Derbyshire captain Samuel Richardson somehow squeezed a ball past his defence and it brushed Dick-a-Dick’s left shoulder. In a rare moment in which the affable, easy-going nature which had impressed all who came into contact with him was momentarily forgotten, Dick-a-Dick complained vociferously that he had not been ready. Regardless, it was the only occasion during the whole tour in which he had to part with his cash.

In October 1868, at the end of the tour, a reception was held for the players in Surrey. Naturally, Dick-a-Dick was chosen to be the side’s representative. His speech was succinct:

“We thank you from our hearts.”

And with that, the side returned to Australia. According to a letter written by a daughter of William Hayman, which is quoted in David Sampson’s essay Culture, ‘Race’ and Discrimination in the 1868 Aboriginal Cricket Tour of England, if Dick-a-Dick had got his own way he might not have returned at all:

“One ‘Flash Dick’ (Dicky Dick) fell in love with a white girl in an Hotel at home [i.e. England] and she would have married him if he had stayed behind but Father made him come.”

So it seems that Dick-a-Dick might have been forced to leave against his will by a management team by now terrified of the Victoria Aboriginal Protection Board which had opposed the tour from the beginning. He left something important behind, however. In 1946 the Lord’s Museum took possession of Dick-a-Dick’s leangle, where it has remained ever since. It is not known where it had been located in the preceding years, but it is certainly fitting that the only tangible artefact – (save for a few withered photographs and scorecards –) for a tour of such cultural and historical significance relates to its star.

***

After the UK tour, Dick-a-Dick and his wife Amelia – how Amelia would have felt had she known how close Dick-a-Dick was to staying in England and marrying a woman there is anybody’s guess – travelled to the Ebenezer mission in Victoria. Dick-a-Dick’s health had swiftly declined following his return to Australia, and he passed away on September 3, 1870. His entire life dictated that it was never going to be quite as simple an end as that, however. While on the tour, Lawrence noted that Dick-a-Dick had taken a particular interest in the stories that he liked to tell the Aboriginal players about Christianity. On his deathbed, Dick-a-Dick decided that he wanted to be baptised, and his wish was granted on July 30, 1870. Shortly before he passed away, Dick-a-Dick supposedly claimed to have seen the face of Jesus.

Australian international Dan Christian will lead an Aboriginal XI squad on a commemorative tour this summer

Australian international Dan Christian will lead an Aboriginal XI squad on a commemorative tour this summer

But there is more. Although Ashley Mallett is convinced of the veracity of the above account, Mulvaney and Harcourt claim that he was spotted at a race meeting on Mt Elgin station in 1884 and lived until the mid-1890s, perhaps under the moniker of Euston Billy. Given that Dick-a-Dick’s story contains enough material for several lifetimes, I would not even be able to rule out both accounts being true.

The Aboriginal XI’s anniversary tour fixtures are below

Aboriginal XI Men

5th June – Aboriginal XI def Marylebone CC by 21 runs @ Arundel Castle

5th June – Aboriginal XI def Marylebone CC by 6 wickets @ Arundel Castle

7th June – Aboriginal XI def Surrey by 5 runs @ The Kia Oval

8th June – Aboriginal XI v Sussex @ The First Central County Ground

10th June – Aboriginal XI v Derbyshire @ 3aaa County Ground

12th June – Aboriginal XI v Nottinghamshire @ Trent Bridge

Aboriginal XI Women

7th June – Aboriginal XI lost to Surrey by 36 runs @ The Kia Oval

8th June – Aboriginal XI v Sussex @ The First Central County Ground

10th June – Aboriginal XI v National Cricket Conference @ 3aaa County Ground

12th June – Aboriginal XI v ECB Academy @ Trent Bridge