CricViz analyst Ben Jones looks at the approach and workload of Jofra Archer in Tests since his debut last summer, and tries to decode how England can get the best out of the speedster.

Jofra Archer hasn’t struggled this summer. He’s averaged 36, taken some important wickets, and his body has held up across three Tests in four weeks. However, in contrast to the glory of 2019, it feels a little flat – understandably. Archer took the world by storm, a force in the World Cup and then the Ashes. He will recover that effectiveness because he’s far too good a bowler not to, but the general sense is still that England are working out how best to use him.

Is he a new ball bowler?

Is he an enforcer?

A speed demon?

An old school line bowler?

With a player this versatile, the question England need to answer is – how do they get the best out of Jofra Archer?

THE QUESTION OF PACE

Is Archer an out-and-out quick?

The issue of Archer’s pace is the most delicate aspect of any discussion surrounding him. Whether or not Archer can ‘come back spell after spell’, ‘crank it up consistently’, has been brought up time after time, sometimes even by the man himself, but also often by those who have another agenda to push.

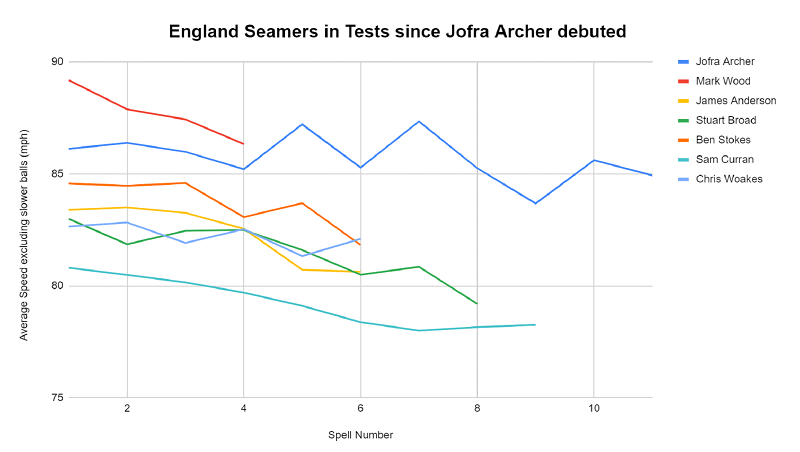

It’s a debate clouded by agendas and misinformation. Archer averages over 85mph in every spell until his ninth. No England seamer – other than Wood – averages over 85mph in any spell.

Wood is the only Englishman who is close to Archer’s speed – indeed, he is quicker than him. Yet since Archer made his Test debut, Wood has bowled 555 deliveries in Test cricket, while Archer has bowled 515 bouncers alone. Since the start of 2019, Archer has bowled 2442 balls in all forms of cricket; Wood has bowled 1229. Wood can bowl as fast as he can because it leads to him getting injured, and because England only pick him for very occasional games.

Since making his debut for England, Archer has bowled more deliveries in international cricket than any England bowler. The only bowler of any nationality to bowl more deliveries in international cricket in that time is Pat Cummins. Pat Cummins’ average speed in that time? 138.07kph. Archer’s? 138.06kph.

With Ben Stokes unavailable, England will be forced into at least one change for the second Test of the series.https://t.co/jDccMlpbjc

— Wisden (@WisdenCricket) August 11, 2020

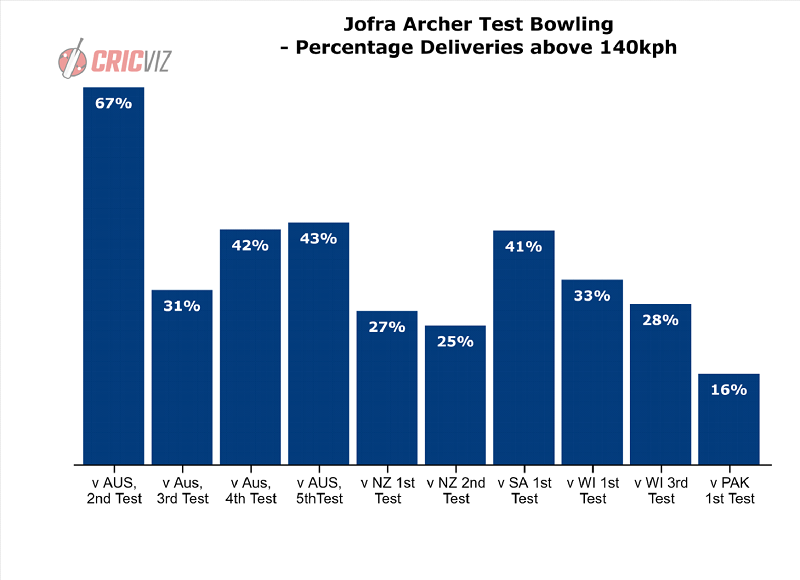

In Archer’s Test career so far, he’s bowled 799 deliveries above 140kph; all other England seamers put together, since Archer’s debut, have bowled 666. If you up the threshold, and switch to old money, Archer has bowled 130 balls over 90mph, while the others have bowled 129.

So since the start of his international career, Archer has the biggest workload of any bowler in the world, apart from one man, who bowls at the same pace as him. And he’s managed to do all that while bowling more heat than every other Englishman combined. His pace has decreased, no question, but simply down to the level that is sustainable for a bowler who is playing as much cricket as he is.

Let’s put questions of pace at the door. Archer may not be lightning quick on demand, but he doesn’t really have a chance to be. You want Archer to deliver Mark Wood pace, consistently? Give him Mark Wood’s workload.

ARCHER THE LINE BOWLER

As has been written about on this site before, there is one rather important reason for the way Archer is treated slightly differently. However, there’s something else at play here.

There is distrust of Archer – or rather, a distrust of his ability – because he has in many people’s eyes proved himself, promoted himself, and brought himself to prominence, in white ball cricket. Before debuting in Test cricket, his most high profile moments had come in the colours of Hobart Hurricanes, Rajasthan Royals, and the England ODI side. There is still – remarkably – a scepticism that a bowler grooved in formats with specific demands and lower workloads, can translate their success into the longer, more traditional, ‘tougher’ form of the game. It ignores the fact that Archer averages 23.79 in the County Championship for Sussex, but no matter.

Some white ball bowlers may struggle to translate their skills into longer format cricket – even from T20 into ODI – because their primary trick is unpredictability, a mastery of variations. Some may struggle because they rely on iconic short-form deliveries like the yorker, or the slower ball, deliveries rendered less effective when the batsman’s main aim (scoring in white ball, survival in red ball) changes. Those are the main obstacles to bowlers crossing over into red ball cricket.

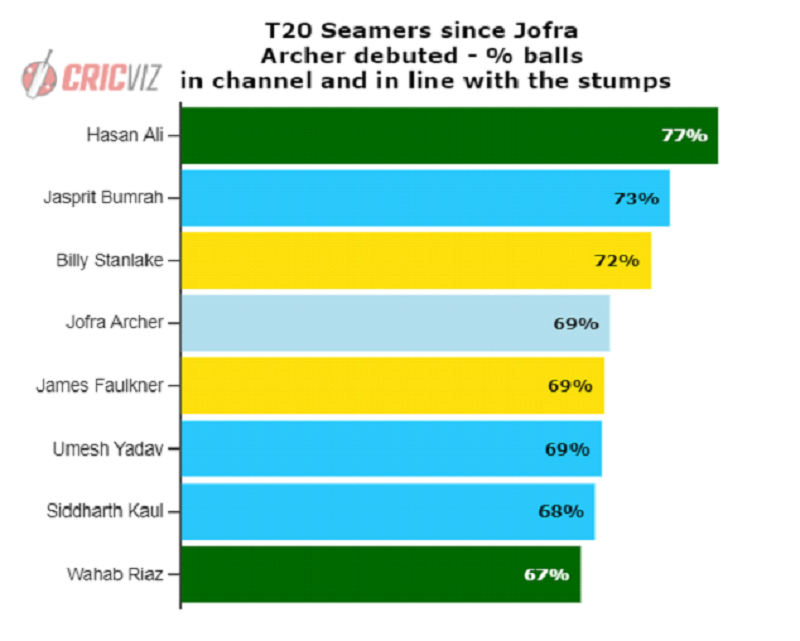

However, Archer’s defining feature as a white ball bowler is something far more durable – an immaculate control of line. Since he debuted in T20 cricket, only a handful of seamers in the world have bowled a higher percentage of their deliveries either in the channel outside off stump, or in line with the stumps themselves.

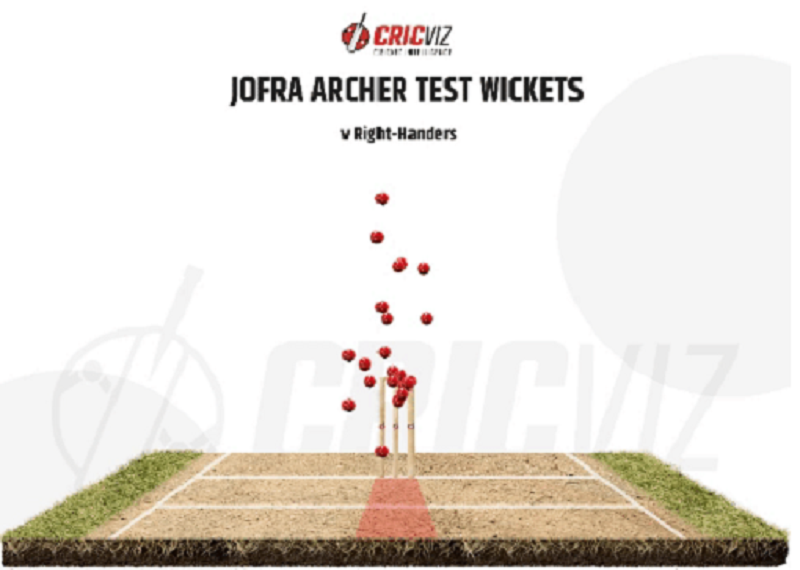

For all the excitement about pace and aggression, if you look at Archer’s Test wickets, it’s this that comes across most strongly. 41 per cent of his wickets have come with balls in line with the stumps; the average for seamers, in Test cricket, is about 29 per cent.

Small samples could be the reason for this slight disparity, but given the volume of work we have seen from Archer in white ball cricket, it isn’t a leap to suggest this will be his pattern going forward. Archer’s primary ability is that of putting the ball on a good line. For all the bells and whistles, Archer is a line bowler.

A SWINGER OR A SEAMER?

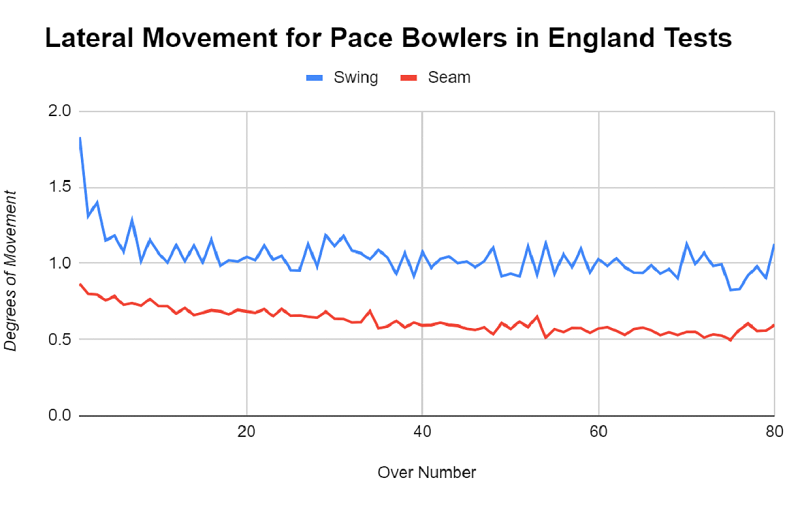

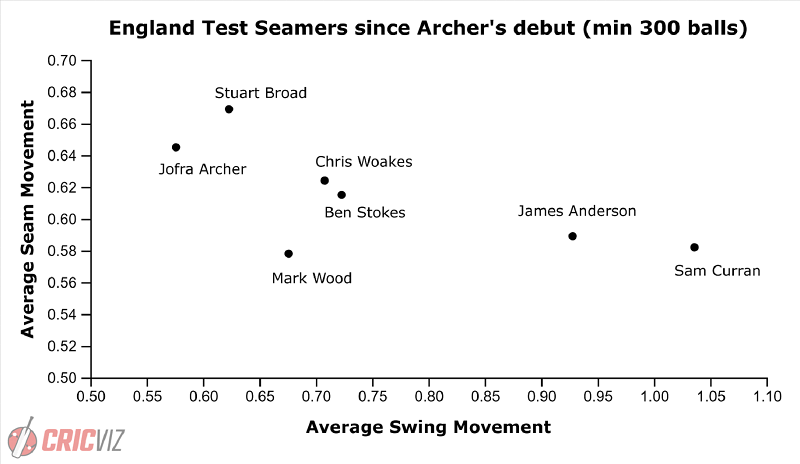

Generally, Archer doesn’t swing the ball. His primary lateral movement is off the seam, and he finds more of that movement than any England bowler barring Stuart Broad.

To confirm that this isn’t distorted by Archer bowling more bouncers than other bowlers, we can look at the figures for just good length and full balls, the ones which swing the most. Looking purely at those deliveries, Archer is seaming the ball, and still isn’t really swinging it.

The pattern remains for Archer when he takes the new ball. Whether he’s trying to (I don’t think so) or not, right now Archer is not a bowler who swings the red ball. In England, swing movement is more obviously weighted to the new ball period than seam movement, the Dukes ball has a more pronounced seam that appears to stand proud for longer. You could argue then, that the benefits of giving Archer the new ball are slim.

ARCHER THE ENFORCER

Linked but separate to the idea of Archer as ‘speedster’ is the idea of The Enforcer. It’s quite an English idea, the notion of nominating a player to bowl bouncer upon bouncer when the pitch has died and you’re behind in the game. Other countries’ sporting sensibilities might feel slightly queasy at the idea of setting up your XI with falling behind at the forefront of your mind.

Before this series, there was a trend of people discussing Archer’s capability with the old ball, highlighting his strength to the attack in this area. In 2019, Archer took 14 wickets with the ‘old’ ball (in overs 40-79), at an average of just 19.64. His extra pace when the ball had gone soft, his control, all were put forward as arguments for why this was a period when Archer stood above the rest. Yet this summer, Archer has taken just one wicket with the ‘old’ ball, at an average of 95.

Archer’s bouncer bowling is quite unique. His bouncer is the most ‘left’ bouncer of any bowler since 2015. You can interpret this as a positive (batsman are nervous enough to not attack him, content to duck and cover) and as a negative (perhaps he’s not ‘at the body’ enough), but the fact is Archer is an unusual bowler when it comes to bouncers. That spell to Steve Smith at Lord’s was evidence that he can get it right, but he has nowhere near the body of work in this role that he has in other areas. If England feel like this mode of attack is necessary in a game, then Wood feels a more natural fit.

CONCLUSION

The one thing Jofra Archer can’t be, is the one thing England know what to do with – a classic 82mph swing bowler. That’s the answer to this question, really. But they can take pointers from the way other bowlers have developed. The model for Archer shouldn’t be Mitchell Johnson, or Jasprit Bumrah, or Kagiso Rabada, but Pat Cummins.

As the axis of Anderson and Broad is slowly broken up in the coming 18 months, and matches where they both play become rarities rather than the default, Chris Woakes will move up and become the new ball bowler.

This leaves Archer a spot to grow into, as a first change bowler who doesn’t need the new ball – and the movement that comes with it – but instead challenges the batsman with excellent control of line at surprisingly high pace for one so consistent. He can bowl bouncers, but interspersed among more normal spells rather than as the sole mode of attack. He may not be able to execute that role as well as Cummins, but that is a very high standard to which to hold a young bowler. If Archer can grow to be a bowler even close to Cummins’ effectiveness in that role, then England will have gone close to maximising the talent in their hands.