Ben Jones analyses the return to form of the Australian opener.

There’s a funny difference in mentality between the cricketing cultures of England and Australia. Eoin Morgan’s England side haven’t lost an ODI series at home since 2015, and have all but swept the board over the last two years, but the default position for most England fans is nervous concern ahead of the World Cup. “Is there enough bowling? What if the pitches are slow turners? Will we choke in the semis again?”

By contrast, Australia have been abysmal in ODI cricket for more than a year, and yet two series wins against India and Pakistan sides rotating as they attempt to find combinations ahead of the World Cup has seen optimism soar. “Best attack in the competition … they’ve got that tournament nous, built in … as good a chance as any other side”. It’s interesting how a culture so used to winning can always see a route back to the top.

Australian cricket’s refusal to accept mediocrity is infectious and usually well-meaning, but it translates into the mainstream coverage of the game, into much of the discussion around the national team. They are presented as either no-hopers or world-beaters. Most notably in recent times, it has translated into the treatment of Aaron Finch.

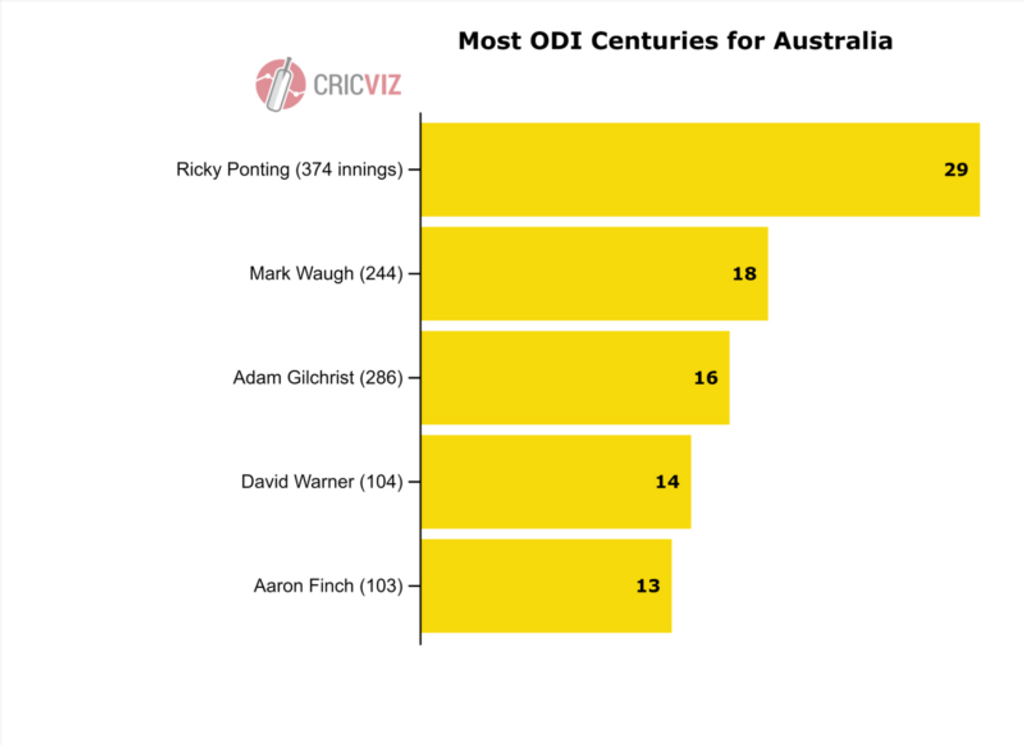

It’s reasonable to say that Finch is a notch below ODI greatness. He is inconsistent and flawed, but prolific and devastating when he hits his stride. On one hand, only 16 Australians have made more ODI runs than Finch; on the other, his average is worse than all but four of them. Equally, he has 13 centuries in this format of the game, and the four Australians with more have all played more matches than him.

In the history of Australian ODI cricket, no batsman has ever made three centuries in three consecutive innings, but few will get closer than Finch did yesterday. He should be held in higher regard, enjoying the cushion for brief failure that comes with sustained excellence.

From this base of appreciation, it’s also important to note that Finch’s dry spell in ODIs has been exaggerated, for two reasons. One, because the rest of the Australian team have been dire, and in such a climate everyone comes under greater scrutiny. Bad players aren’t given time, good players are held to higher standards, and everyone gets raked over the coals.

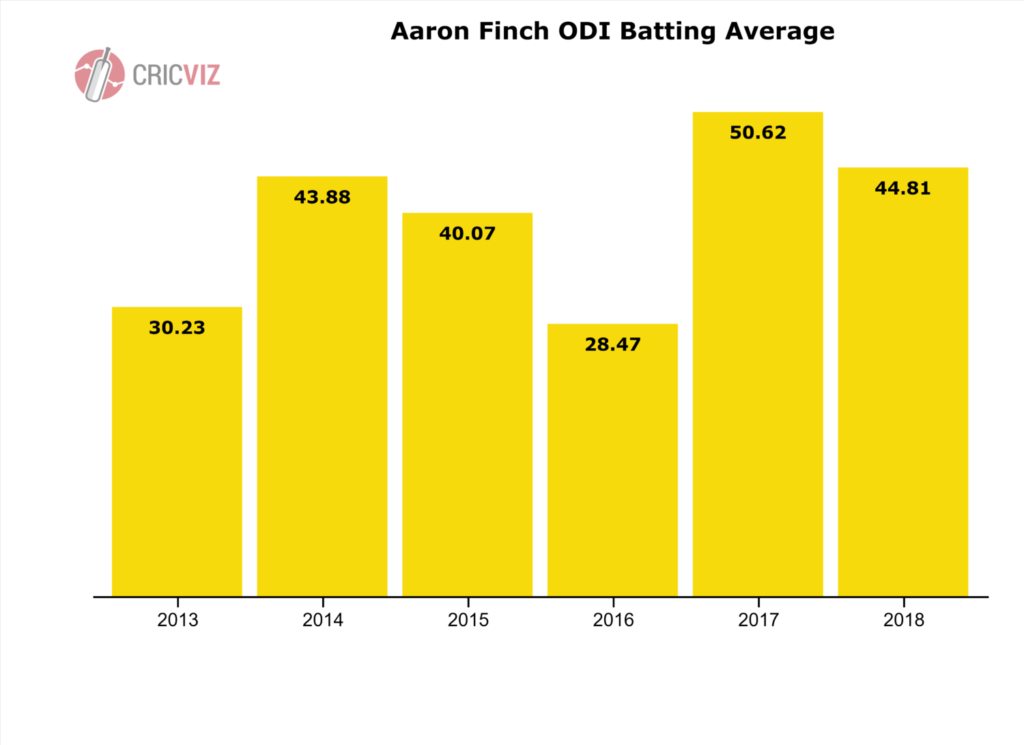

Two, because of his shonky and unconvincing performances in the Test series against India, where the general cricketing public grew frustrated with Finch’s inability to get them off to a solid start. Whilst his decline has been intensifying in 2019, last year’s average of 44.81 was actually the second highest average Finch has ever recorded in a calendar year. He has hardly been in terminal decline.

However, that record was boosted by an excellent performance against England at the start of the year, and for the remainder of 2018 Finch averaged 27.25. With the question of how to incorporate the returning David Warner an increasingly pressing issue, Finch’s place in the XI was coming under ever greater scrutiny from many commentators.

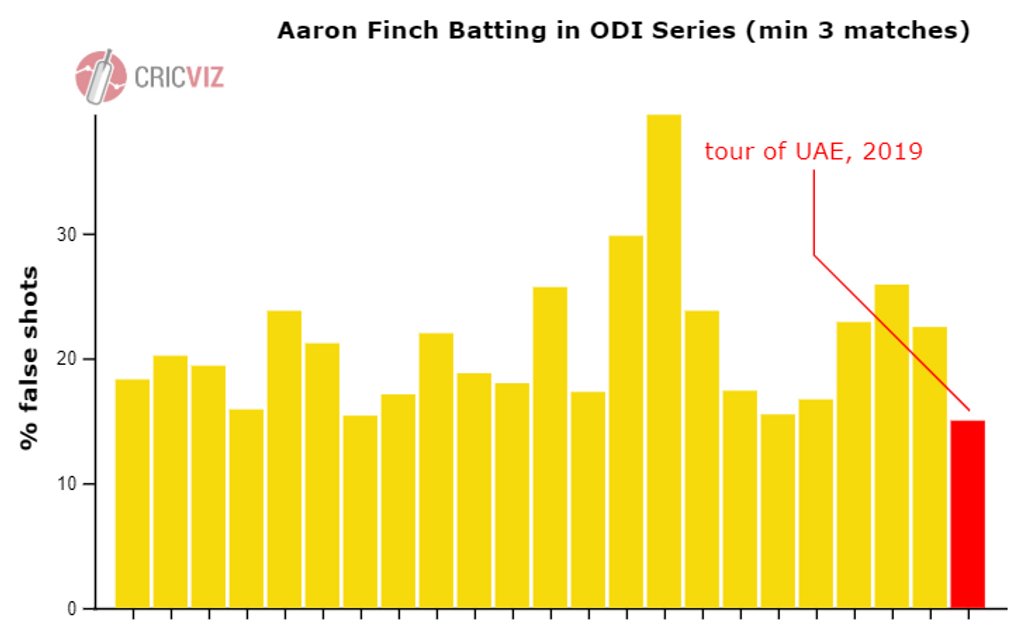

Yet two centuries (and a 90) in three matches against Pakistan – the holders of the most recent global ICC ODI tournament – have dismissed any questioning of his place in the XI. Playing with remarkable control that looked beyond him just weeks ago, only 15 per cent of his shots have resulted in a false stroke, the lowest figure for any series he’s played in (min 3 matches). He has been supreme.

So how did he orchestrate this turnaround?

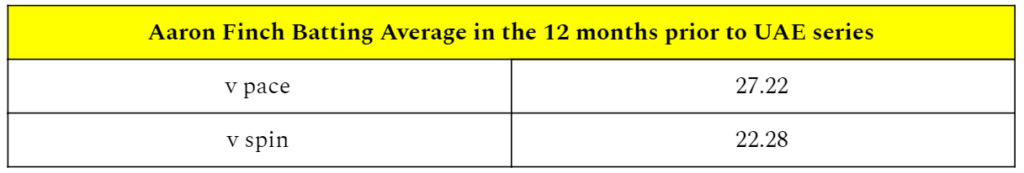

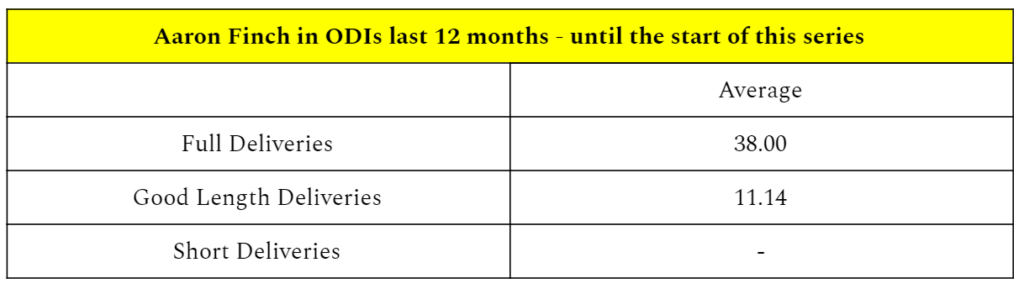

Well, the first thing to do is isolate where Finch’s issues specifically lay. In the 12 months prior to this series in the UAE, he averaged 25.06 in ODI cricket, but wasn’t struggling disproportionately against either pace or spin. There was also no evidence of a clear kryptonite head-to-head – the bowling type which dismissed him most often was right-arm pace, but he still averaged 23.55 against those bowlers, very much in the same ball park as the overall record. He had been struggling uniformly across the board.

On the other hand, there were patterns to his dismissals. Against seamers, he was troubled particularly by good length bowling – hardly an unusual weakness, but the severity of his trouble is notable. Against balls pitching 6-8 metres from his stumps, Finch had been averaging just over 10. He was negotiating the fuller bowling, and wasn’t dismissed at all by short pitched deliveries, but that difficult in-between length was causing him all sorts of problems.

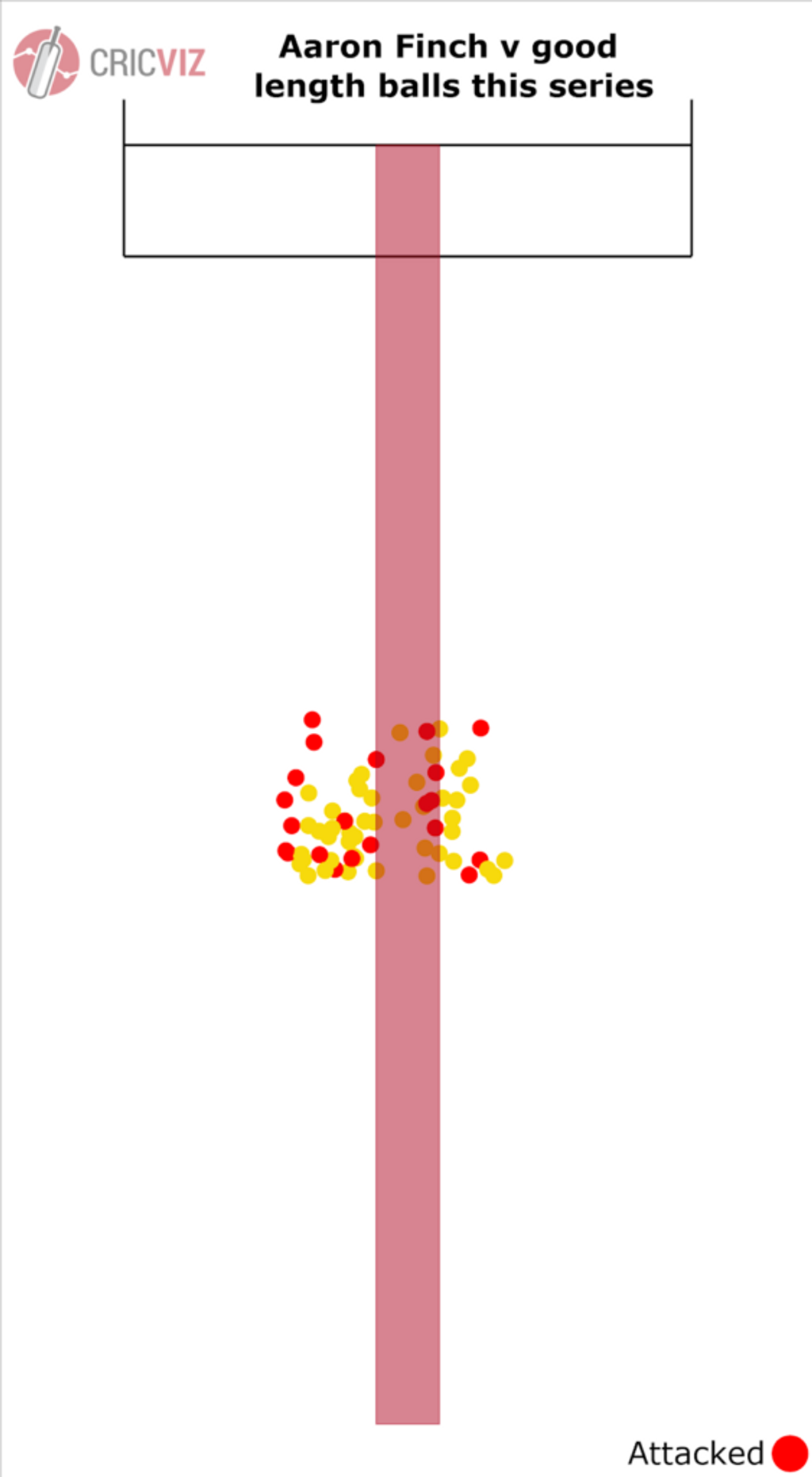

Some of his recovery in this series could be attributed to improvement against those deliveries. In the last three matches in the UAE, he’s averaged 33 against good length bowling, significantly more secure than he has been. He’s only scored at 2.95rpo against them, but Finch appears to have made a conscious decision to be very selective; the length balls that he has gone after have been wider deliveries. Typically, if the ball has been on a good length and a good line, Finch has been happy to defend or rotate.

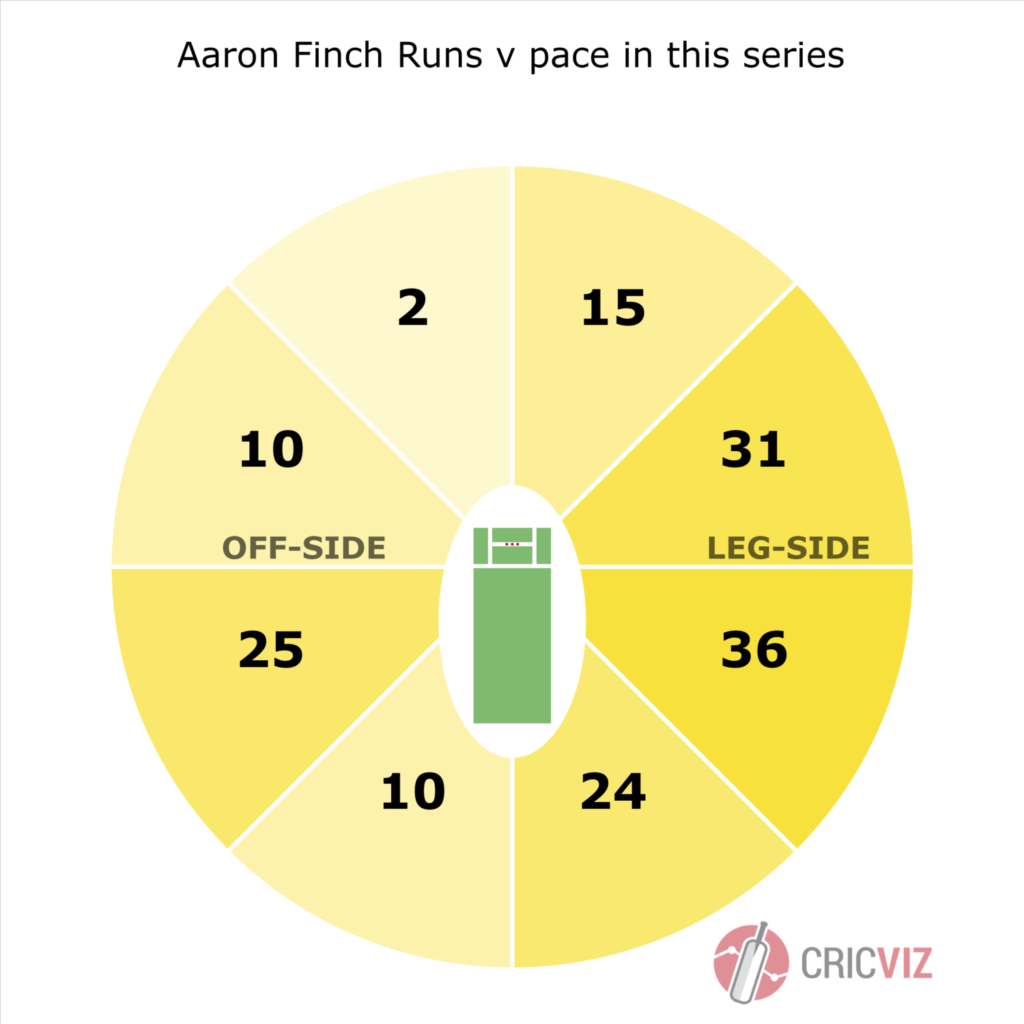

Whilst his attacking against good length balls appears to be more focused on wide deliveries, Finch also appears to have made a concerted effort to play straighter against the seamers. In this series, 22 per cent of his runs have come in ‘the V’, the highest figure he’s recorded in a bilateral ODI series since the Champions Trophy. It’s a basic principle, but it seems to have served him well.

However, fundamentally there hasn’t been a change in approach substantial enough to account for Finch’s massive upturn in fortunes. For that, we have to look at what’s been happening 22 yards away. Bluntly, the bowling Finch has faced has not been of the same standard he has been coming up against over the last year.

During the India series in Australia, the Expected Dismissal Rate (Tracking Only) of the balls bowled to Finch was 25.5**, meaning that regardless of who had faced those balls we would expect them to be dismissed every 26 balls. Whilst Finch’s own dismissal rate of 17.6 in that series shows that he was still under-performing, the quality of the bowling was seriously high and his struggles were understandable. In this series, the Expected Dismissal Rate (Tracking Only) of the balls bowled to Finch has been 41.8. As the pressure has lessened, Finch has flourished.

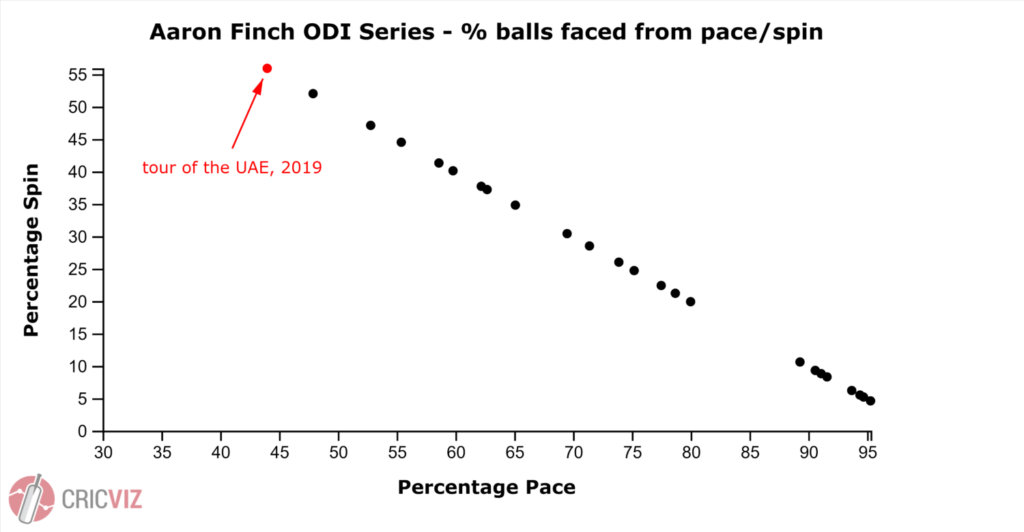

The bowling has also been of the right type for Finch. Whilst his troubles in the last year have been against all bowling, he’s historically been a very strong hitter against spin; it is hardly a surprise, then, that his return to form has come in a series where 56 per cent of the balls he’s faced have been from spin bowlers, the highest percentage for any ODI series he’s ever played.

Of course, that shouldn’t diminish his achievement. Presented with an opportunity against a weakened attack in conditions that should suit him, he has been ruthless, which is admirable and indicative of a base talent level which should never have been in doubt. Helmet off, cap on, chewing away on his gum as if to show that, seriously, this isn’t his first rodeo. There’s no ‘chicken and egg’ question here – the improvement brings the swagger with it, not the other way around – but it is hard to ignore how nonchalantly imposing Finch appears when he’s in this sort of groove.

The wider implication of this surge of form is Australia will now have to confront the Warner issue head on. Finch’s place is locked, only the identity of his partner up for debate now. In a way, the loss of Finch’s form could have led to an easier call for Cricket Australia, given that they could include both Warner (a genius, but one out of match practice and with a huge political cloud over him) and Khawaja (an inferior player to both Finch and Warner, but bang in form) in the XI, without making any particular compromise.

Now, they have to make a call – deal with the side effects of recalling Warner, or accept the limitations of Khawaja. Both have benefits, both have flaws. What is decided however, is that the man walking out alongside them will be a strapping Victorian, and one peaking at just the right moment.

**This figure is calculated using CricViz’s Wicket Probability Model, which uses historical ball-tracking data to assess the likelihood of any delivery bringing a wicket**