Over the course of six issues, Wisden Cricket Monthly‘s team of writers are tackling all aspects of cricket’s diversity crisis. To kick off the vital series, now being published on Wisden.com, WCM editor-in-chief Phil Walker looks at the game’s vexed and historically complex relationship with inclusivity.

First published in issue 34 of Wisden Cricket Monthly

First published in issue 34 of Wisden Cricket Monthly

In late May 2014, the then-ECB chairman, Giles Clarke, gave an interview to the BBC. It was a brave move going public at the time, and possibly a foolhardy one, but Clarke was determined to deflect some of the heat from his captain, Alastair Cook, and own the “appalling” Ashes whitewash just suffered in Australia while positing the idea that the atmosphere around the squad had since become the best he’d seen “in quite a long time”.

The mood was mutinous. English cricket had turned in on itself. Heads had rolled, and none bigger than Kevin Pietersen’s, the outlandish South African genius who had outstayed his welcome. After addressing the Pietersen question, Clarke was then asked about Cook himself. “He is a very determined guy, a very good role model,” he began, seizing the chance. “He and his family are very much the sort of people we want the England captain and his family to be.”

Open Account Offer. Up to £100 in Bet Credits for new customers at bet365. Min deposit £5. Bet Credits available for use upon settlement of bets to value of qualifying deposit. Min odds, bet and payment method exclusions apply. Returns exclude Bet Credits stake. Time limits and T&Cs apply. The bonus code WISDEN can be used during registration, but does not change the offer amount in any way. Bet on the IPL here. 18+ please gamble responsibly

Stepping into the feverish atmosphere that always follows Ashes failure, Clarke probably thought he was helping, though it’s moot whether Cook and his family felt the same way. The line reached back through the ages, shining fresh light on a game evidently still hidebound by notions of propriety and class. So often through its long and ludicrous history, observes Derek Birley in his magisterial A Social History of English Cricket, cricket has appeared lost “in a dreamworld of past glories and outworn social attitudes”. As recently as 2014, the ECB chairman resurrected it.

Cook’s opening partner on that Ashes tour was Michael Carberry, to date the only Black England-born cricketer to make his Test debut this century. Despite standing up to Mitchell Johnson’s fury as well as anyone that winter, Carberry would not play another Test match. The previous summer, the Nightwatchman quarterly had published a piece lamenting the lack of chances afforded to Carberry, a prolific county run scorer, at the top level. “It stretches credulity that the ECB does not understand the implications of being perceived to deny him his chance,” wrote Ed Weech. When Clarke got wind of it, he demanded a full retraction and, among other sanctions, banned the Nightwatchman’s sister publication, All Out Cricket, from talking to any England players until a full apology had been made, writing to the editor that “the allegation that the ECB is not open to all parts of society in every element of the national summer sport is a flat lie”.

The welter of harrowing personal accounts which have come out in recent weeks expose the flimsiness of Clarke’s position. In June, Carberry described English cricket as “rife” with racism. “The numbers tell you everything,” he said. “There are no Black people in prominent positions in the game at any level, right the way down to playing level. There are no Black people in positions where you can ultimately stand toe-to-toe and make the big decisions.”

By the end of last season, English cricket could offer just a single Black state-educated player in first-class cricket. Mark Alleyne remains the only Black county coach this century, and Vikram Solanki, appointed last month by Surrey, is the only British-Asian head coach in the county game. As for the British-Asian playing contingent in professional cricket, this year’s Cricketers’ Who’s Who throws up just 19 names, this despite the fact that British-Asians make up 30-35 per cent of the game’s active playing force at grassroots level. In 2018, the number of BAME players in county academies (aged 15-18) was running at 23 per cent, and yet in the same year that figure dropped to eight per cent across the full professional squads. Somewhere down the line, the chain gets broken.

“Cricket, like football, merely reflects wider racism, inequality, class structures, and all other kinds of problems in society,” says Dr Michael Collins, associate professor of modern British history at UCL. “This means that there is a supply problem. It’s not cricket that corrupts people, it’s where they’re coming from, and how they’re educated. At the same time, there are things that can and should be done to address internal cultures and practices.

“At county and especially club levels, more could be done to encourage consideration of how diverse and inclusive clubs are in terms of reflecting local communities. Are they a force for inclusion, or do they entrench separation? The idea that all the ills of cricket simply stem from wider society should not prevent critical self-evaluation and reform.” Collins is currently researching how cricket as a social and cultural activity was integral to the way in which migrants from the Caribbean found ways to settle in Britain. A key part of his Windrush Cricket Project considers not just why cricket meant so much to first-generation Caribbean migrants, but why it means so little two generations later.

***

Cricket’s narrowness is not just confined to race. Collins cites the inequities inherent in a system that favours cricketers from fee-paying schools, rising via access to the best facilities and coaching to the top of the professional scene. According to data compiled by the charity Chance to Shine, in 2013 no more than half of registered county cricketers went to state schools. The scholarship programme, which has benefitted the likes of Joe Root and Jos Buttler, is often used as evidence to mitigate against charges of elitism, and there is some truth in that.

But while these gifted cricketers get access to the best the system can offer, what of those they leave behind? A few success stories speak of little but the largesse of private money. Any notion that the modern professional game can lay claim to being a meritocracy is laid bare by those numbers. “Cricket at the top level is now increasingly the preserve of private schools,” says Collins. “It’s a crying shame how few county cricketers emerge from state schools.”

Admittedly the decline of cricket in state schools is nothing new. In 1965, according to the Government Social Survey, nine out of 10 men had played the game before they were 14, with two-thirds of them playing at state school. In the years that followed, those numbers fell sharply. Derek Birley, who was a professor of education when he wasn’t writing cricket books, writes that while “rising costs and the elaborate facilities required” were legitimate reasons for the tail-off, the decline coincided with the proliferation of big comprehensive schools, “offering a wider range of recreational activities than the space-consuming elitist pursuit” of old-world genteel cricket.

Michael Carberry is the only Black England-born cricketer to make his Test debut this century

Michael Carberry is the only Black England-born cricketer to make his Test debut this century

In 1965 cricket was the second most-played outdoor sport for adults, along with angling; by 1980, the game had drifted to 10th, behind golf, tennis and bowls. Birley cites, too, an article in the Times Educational Supplement bemoaning the fact that fewer than half of the 130 secondary schools in Hampshire took more than a casual interest in cricket. That piece appeared in 1982. The tension between space, cost and the march of modernity has been at the heart of cricket’s struggle for generations.

The decades which followed the hyper-politicised Eighties were marked, if they were marked at all, by neglect and complacency. At a governmental and administrative level, cricket was allowed to drift ever further to the margins. While the game continued to thrive in provincial middle-class areas, in the ever-burgeoning inner-cities, where BAME people and the white working-class tend to live, it was squeezed to the edges. A clutch of Black Caribbean-migrant cricketers in the higher reaches of the professional game provided a convenient smokescreen, but beneath the surface cricket was fading from urban life. “It’s the political economy of class,” says Collins. “A lot of people in inner-city areas are simply excluded from cricket.” As the century came to an end, bringing to a close a calamitous decade for the England team, it was hard to escape the sense of an unbalanced game swaying just to stay on its feet.

The ECB were regrettably slow to see the signs. Tim Lamb, who was the body’s chief executive from 1996-2004, concedes that “naivety” may have clouded his judgment at the time. “Even when I was in post as chief exec,” he tells WCM, “I thought that cricket was a massively diverse sport, you know? I was never consciously aware that there was any deliberate racist activity or attitudes in the game.”

His recollections are hard to stack up, given the fact that in 1999 the organisation, after a number of allegations, commissioned its own report into issues of racism in cricket, in which 58 per cent of respondents said they believed that racism still existed in the game. Lamb even spoke to the BBC at the time about the report’s findings. “We were always aware that some element of racism existed and we have not sat around idly and let it fester,” he said, and promised that the board would implement a series of wide-ranging recommendations. “Maybe, looking back, we weren’t as diverse as we should have been,” he says now. “But it wasn’t some premeditated grand masterplan.”

***

There is no room for complacency now. The English century has been shaped by a series of subsequent events and societal shifts which have coalesced to bring us to this point. Some will argue that Test cricket’s removal from terrestrial television after 2005 was the moment when cricket fixed its cult of inaccessibility. Others will counter, with good reason, that the ECB were given little option, in the face of indifference from the big terrestrial channels, but to take the money and run. Lamb himself, who was privy to that decision though not an influential figure in it, concedes that there must be some “adverse legacy” to taking cricket off terrestrial television. “There has been some downside – if you have to pay to watch something, a lot of people aren’t going to do it, or be able to afford it. But without that money, areas of the game that had been underfunded in the past would have stayed underfunded.”

Less divisive of course was the roll-out of Twenty20 in 2003, a county-lifeline that mushroomed into a global phenomenon, clearing the ground for the creation of its bastard cousin, The Hundred. Both concepts stemmed from a belated realisation that the game was losing support among new audiences. But while Twenty20 was rolled out as a bit of fun, a shot in the dark, its offshoot carries a grimly heavy burden. The catchphrase – ‘You’ve got to see it to be it’ – is no longer an unutterable line at the ECB, but a guiding principle. New teams, new people, new demographics, new everything. Time is running out.

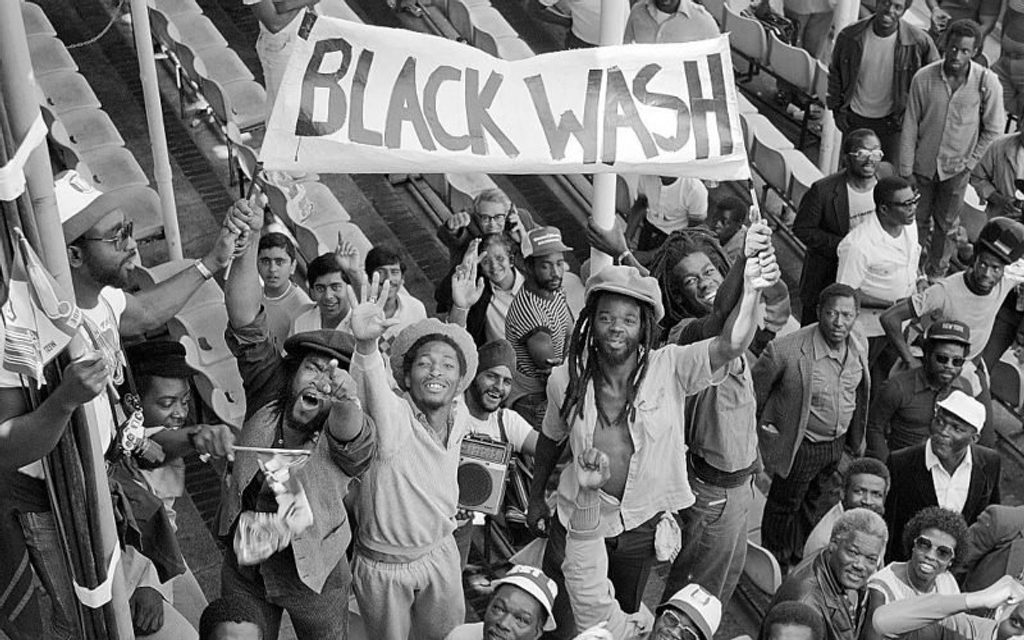

West Indies fans celebrate the 5-0 “Blackwash” at The Oval in 1984

West Indies fans celebrate the 5-0 “Blackwash” at The Oval in 1984

The ECB is a more evolved organisation today, and it needs to be. Its partnership with Chance to Shine continues to bear fruit, providing financial backing to the charity’s mission to spread cricket into state schools and local communities, which has to date reached over four million kids – 46 per cent of which are female – in over 15,000 schools and 179 community projects. Their Street projects have gained traction in inner-city space-deprived areas, working with ‘non-traditional’ community cricket clubs to help bring down some of these barriers.

The ECB’s response to the juddering testimonies of Carberry and others has been encouragingly frank. Earlier this month they unveiled their Diversity and Inclusivity Strategy, with its promises to increase opportunities for BAME individuals across playing, coaching and employment positions, and a commitment to increase diversity in leadership across the wider game. A new coaching bursary for Black coaches will also be introduced, with increased provision for cricket in primary schools, particularly those which are the most ethnically diverse. “We have had to confront some uncomfortable truths,” admits chief executive Tom Harrison.

Many will read these calls to action as little more than tokenistic soundbites. They will say that we have been here before, and be within their rights to say so. But reading through these latest bold commitments, I was put in mind of something Lord Patel once said. Patel, a British-Asian from Bradford who rose to become chair of Social Work England and take a seat in the Lords, served for five years as an independent ECB director. “The new ECB leadership have a tough job,” he told me. “But they’re doing it for cricket, not for personal gain. I don’t mean they weren’t before… but it felt like it.”

Ultimately, of course, the fight rages way beyond cricket’s messy corner. It’s not as if the ECB or its forerunner, the TCCB, personally closed the school playing fields, demonised the working class, drove the deep underlying insecurities about Britishness that spawned the Tebbit Test, drew up “a hostile environment” for immigrants or shaped the cultural shifts that would have made cricket an outdated irrelevance to people anyway. Nor did they control the counties – they didn’t appoint the bigoted youth development officer, or the academy coach who looks the other way, or the racist who runs the under 13s. Prejudice permeates everywhere.

This struggle, the defining struggle of the time, is about challenging the structures of a society which has been ordered to serve the advancements of those who built it, to the exclusion of prickly demographics which are too complicated to address. Cricket, historically, has tacitly approved the status quo. No longer can it stand.