England’s Test team are attempting Total Cricket – and others could follow their bold lead, says CricViz analyst Ben Jones.

Joe Root’s century at Pallekele was the most important of his career. It wasn’t his finest (Johannesburg takes that crown), his most dominant (The Oval 2014) or the most fun (Trent Bridge 2015), but of all of his tons it could be the one which has the most influence and the biggest effect on the rest of his career.

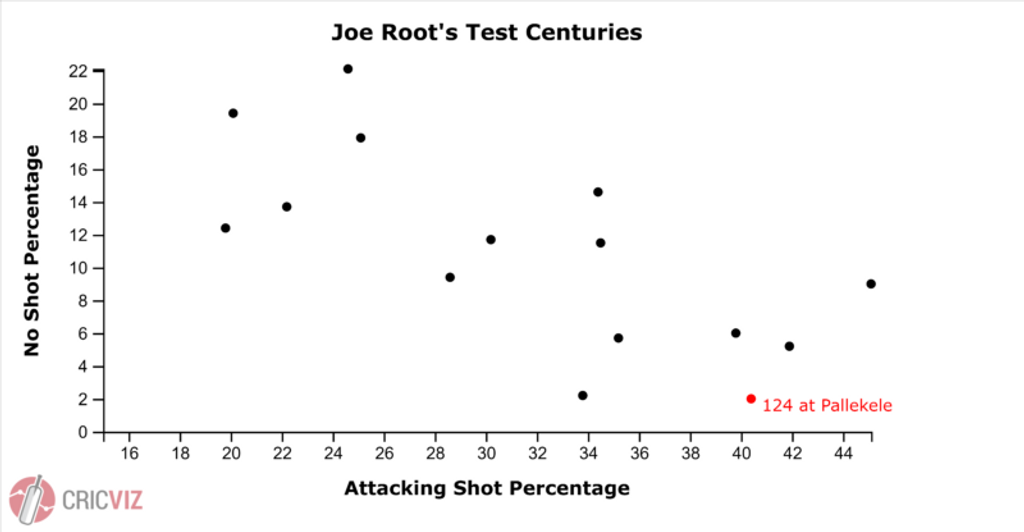

It was a defining innings in a tight Test, but it is the nature of the innings that caught the eye. The England skipper has never made such a defining contribution to a Test match whilst showing such attacking intent. Of Root’s 15 centuries, this one saw him leave the lowest proportion of deliveries, choosing not to play at just 2% of his balls faced. Perhaps more revealingly, only two of those innings have involved more attacking shots. After all the talk of aggression and positive intent, this was Root stepping up and practicing what he preaches.

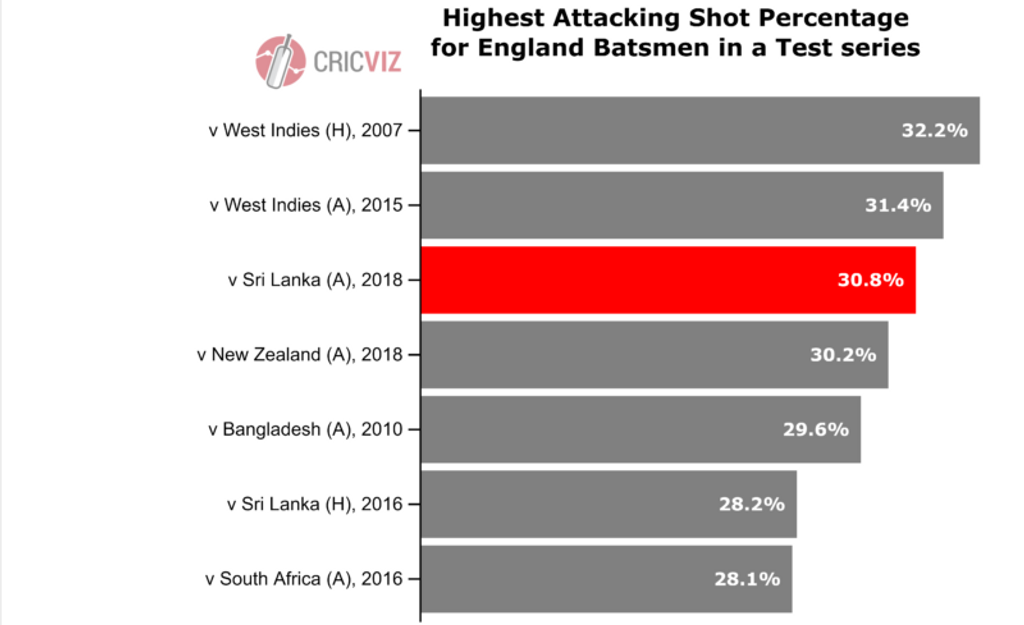

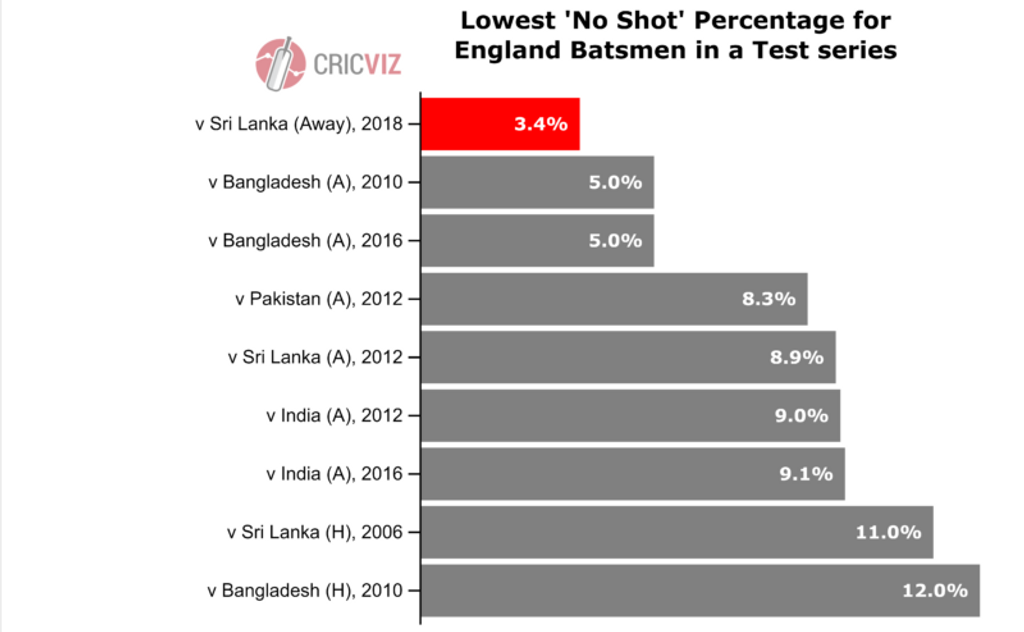

And lo, the England team as a whole have started to do so. Their attacking shot percentage this series is the third highest for any in the CricViz database, which dates back to 2006. In the mould of their captain, and of their white-ball alter-egos, they have refused to take a backwards step. Currently, England have left just 3.4% of their deliveries over the two Tests in Sri Lanka, their lowest figure for any series in the CricViz database. Whilst this is in part a consequence of how much spin was bowled in the Test match, it still says a lot about England’s approach.

Their aggression came most notably through their use of the sweep. Whilst it looks delicate and designed to rotate the strike, the sweep is among the most attacking shots available to batsmen, given it’s relatively high average scoring rate of 9.16rpo and relatively low average dismissal rate of 22.3. England played 143 sweeps, reverse-sweeps or slog-sweeps in the Pallekele Test, the most of any team in a single Test in our database. Root’s men went at Sri Lanka.

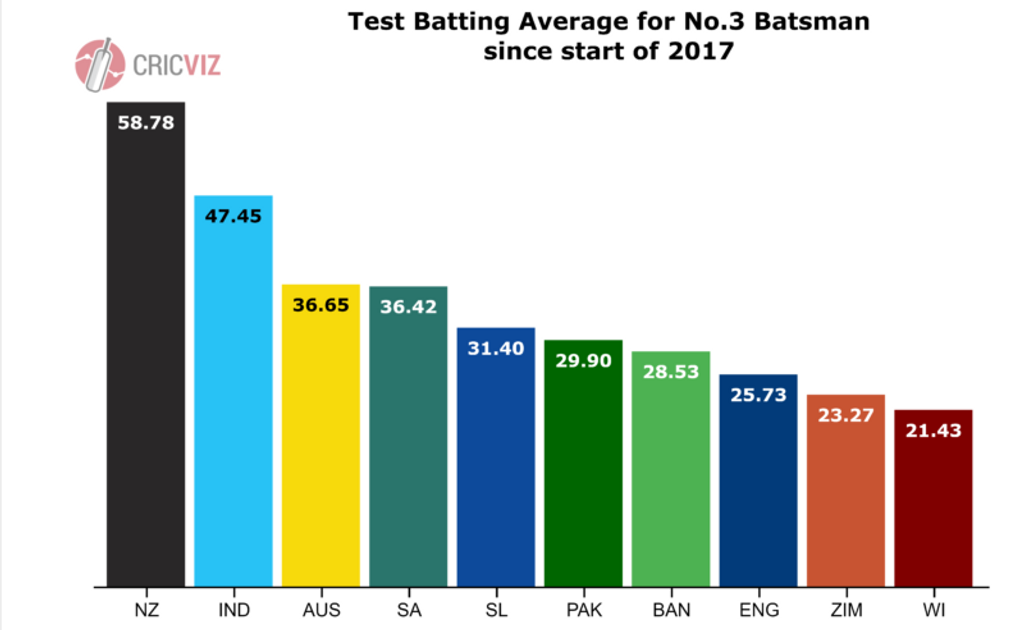

For all those that bemoan England for being too loose and too attacking, this makes sense as a strategy, because for a while now, England’s batting has been a significant issue. Their number three doesn’t make runs, they’re regularly collapsing, and their top six has among the lowest averages in world cricket. Over a prolonged period, England have proved themselves unsuited to heavy scoring in a traditional manner. They need to try something different, to zig where others have zagged, if they are going to succeed.

So they are trying something different. England’s batting has been very attacking in Sri Lanka, but it is set-up to do this effectively. A batting line-up with the depth of England’s can afford to take extra risks, to try and play at a higher tempo, because there is a far greater quantity of players capable of playing match-winning innings. England’s relatively unique player pool means that their No.9 has 10 first-class hundreds, and their No.8 has a Test batting average of 37.77. Of the batsmen above them, most are phenomenal white-ball players who are suited to playing in this style. Importantly, this batting depth really doesn’t compromise their bowling – they have all bases covered. Playing six bowlers, covering the five main bowling techniques, allows them to deploy a tactic not unlike the match-ups which dominate white-ball cricket, targeting batsmen with the bowling type they struggle most against.

England’s approach is comparable to the well-drilled fluidity of Pep Guardiola’s Man City

England’s approach is comparable to the well-drilled fluidity of Pep Guardiola’s Man City

The headline before the Test was that Ben Stokes would be batting No.3 in Pallekele. Yet in the second innings, Root effectively took up the position, coming in ahead of the Durham man. Fluid batting orders allow England to promote and demote batsmen according to the situation, not according to what’s shown on the scorecard before a ball is bowled. Opening up with Jack Leach in the second innings could be nothing more than a quirk of the match situation, but it suggests that this side are unencumbered by received wisdom. If they think something is a good idea for the current moment, they’ll try it. That mindset is valuable.

What’s more, this approach and ‘philosophy’ captures the sporting zeitgeist rather well. Mainstream English sports fans have never been more tuned into the idea of all-out attack as a model for success. Pep Guardiola’s Manchester City side are rewriting the rulebook on how football is played in Britain, dominating the Premier League with a style focused on swarming the opposition with technically gifted players, fluid in position and intelligent in possession. They have a structure, and are intensely drilled as both an attacking and a defensive unit, but it is a malleable structure organised through repetition, not rigidity. The style was mocked by a certain kind of British traditionalist when Guardiola first attempted to implement it, for being too soft, not showing enough character, for lacking the values of old. Sound familiar?

Yet City have swept all before them, and attitudes are beginning to change. Fans are starting to question whether ‘passhun’ is that desirable a virtue, whether ‘not wanting it enough’ is actually the reason behind a defeat, and the sense is of a sea-change in how most people – how actual fans – think about the game. Gareth Southgate’s national side have been embracing a technical, fluid style, and it’s winning hearts and minds, as well as plenty of football matches. Could this England Test team, at this moment, be at the beginning of a similar journey?

Root’s second-innings century in Kandy may be his most significant

Root’s second-innings century in Kandy may be his most significant

Part of the reason why many cricket fans will be resistant to Root’s new strategy is that there isn’t a proper vocabulary for cricketing strategy. You are attacking, or you are defensive. A captain “goes on the attack” or “goes on the defensive”. There is no lexicon for tactics, which does everyone a disservice. So let’s try and solve this, by creating a vocabulary of style which accommodates more than just the binary of attack and defence, Stop and Go, black and white. Because what England are doing isn’t simply All-Out Attack. It’s cleverer than that. So let’s give it a cleverer name: Total Cricket.

Among the most well known tactic in football is Total Football, an earlier incarnation of what Guardiola’s City side have deployed over the past few seasons. Established at Ajax in the 1960s and later at Barcelona in the 1990s (the common thread between both being the Dutch legend Johan Cruyff), it’s key principles are attacking fluidity. This seems to share an ethos (as much as it can across sport) with this England side, a team of all-rounders constantly rotating roles and position, according to the situation. Our aim is to try and widen the tactical vocabulary available when discussing the game, and there are few better examples to borrow. It’s a sexy name – let’s borrow some of that glamour, and make it easier to sell this new style to a public who will, in part, be reluctant and nervous.

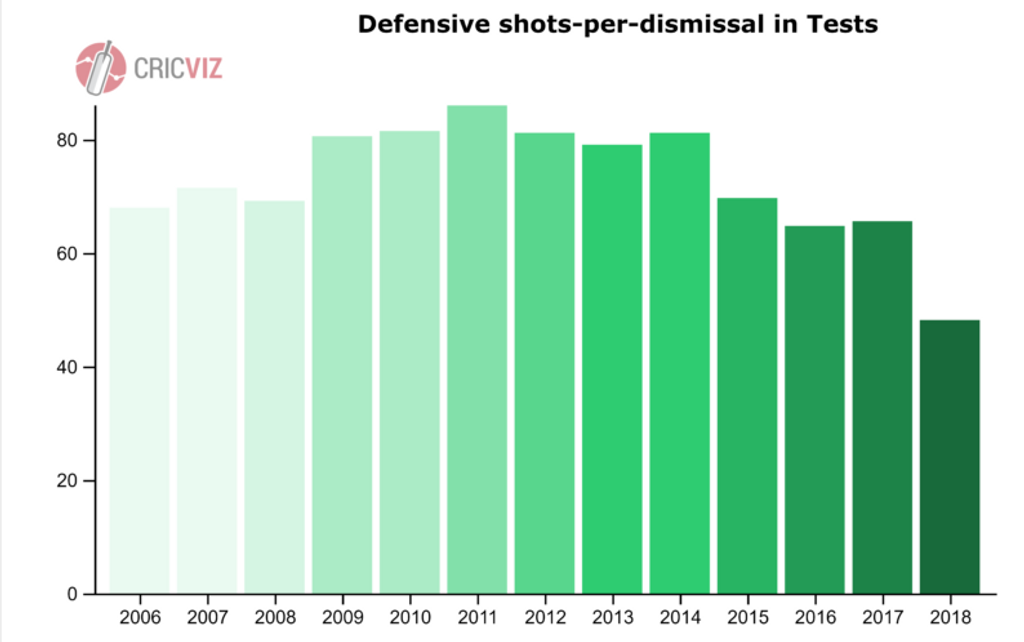

It’s important we label this style correctly, because there’s plenty to suggest that others will adopt it. Moving towards a durable, attacking version of Test cricket makes sense, given that white-ball cricket has improved aggressive batting hugely, and the pool of players coaches are drawing on has never been more skewed towards scoring quickly. It’s not just a truism that defensive techniques are getting worse – the average defensive stroke is significantly more likely to lead to a dismissal than it did a decade ago.

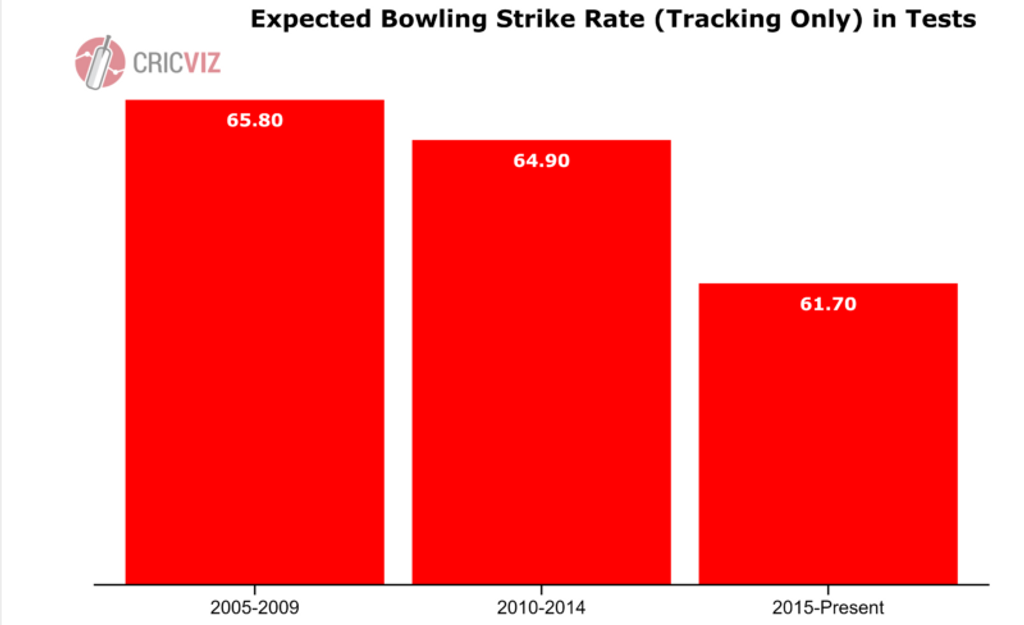

What’s more, batting is getting harder. Using CricViz’s Wicket Probability Model (see here for further explanation), we can see the quality of bowling (and help from conditions) has improved significantly over the past three years. Between 2006 and 2014, the average delivery should have taken a wicket every 65.8 deliveries; since the start of 2015, that’s fallen to 61.7. Expected bowling averages have fallen from 33.44 to 31.6, based on the ball-tracking data alone – it’s tough out there for Test batsmen. In the face of more threatening bowling and more difficult conditions, counter-attacking with a longer batting order is a very reasonable option.

It is not hyperbolic to suggest that if Root’s team can keep this style up, then they could be building a template for the rest of the world in terms of how to play Test cricket. That isn’t to say that they are going to become a great side (though seven wins in their last eight Tests is solid form), but rather that they might inspire other sides to play like them, to improve on their model, to take this idea and run with it. It requires a certain level of risk, sure, but you can’t start a fire worrying about your world – or your batting order – falling apart. For England, Total Cricket is the way forward, and soon it could be for everyone else.