With England returning to Sri Lanka for an ODI series for the first time since 2014, Patrick Noone analyses how things have changed for the visitors since their last tour.

Patrick Noone is an analyst at CricViz, the cricket intelligence specialists

England travel to Sri Lanka to play an ODI series with a World Cup looming on the horizon. In one sense, history is repeating itself. The last time England toured Sri Lanka was in 2014 for a seven match series that formed part of their build-up for the 2015 World Cup.

However, that is where the similarities between that tour and this one end. Eoin Morgan’s side is a very different beast to the uncertain, unsettled and unravelling outfit that meekly surrendered to a 5-2 loss four years ago. Back then, Alastair Cook was captain for what would turn out to be his final series in international limited-overs cricket and England were sleepwalking towards a humiliating exit from the World Cup in Australia and New Zealand.

England are actually attacking less than they were when Cook was still opening the batting

Fast-forward to now and the landscape is almost unrecognisable. England are the world’s number-one ranked team in ODI cricket and favourites to win next summer’s World Cup on home soil. The transformation has been as rapid as it has been exhilarating, with England now seen as among the most entertaining teams in the 50-over format, particularly with the bat.

What is striking when comparing the previous series to the present day is how many of the same individuals are involved. Seven players named in England’s ODI squad for the upcoming tour featured in at least three of the seven matches during the 2014 series: Eoin Morgan, Jos Buttler, Ben Stokes, Joe Root, Chris Woakes, Moeen Ali and Alex Hales. At least five of those players are guaranteed to be in the first XI when England take to the field in Dambulla on October 10, so what has changed?

One of the first answers that is generally put forward to answer that question is ‘mentality’. That England were previously hamstrung by an over-reliance on data analysis and thus prevented from expressing themselves freely enough to succeed in the modern game. Whereas the post-World Cup era has been one of run-drenched success thanks to a newly-obtained licence to attack. There is some truth in this assessment, but it is an overly simplistic one.

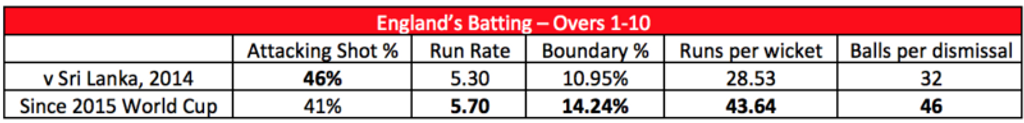

The 2014 series saw England attack 45.7% of the deliveries they faced in the first 10 overs and 48.4% overall. Since the World Cup, those figures are 41.0% and 47.7%, respectively. So England are actually attacking less than they were when Cook was still opening the batting. In fact, England have been more attacking in just seven of the 17 bilateral ODI series they have played since the Sri Lanka tour.

Top-order transformation

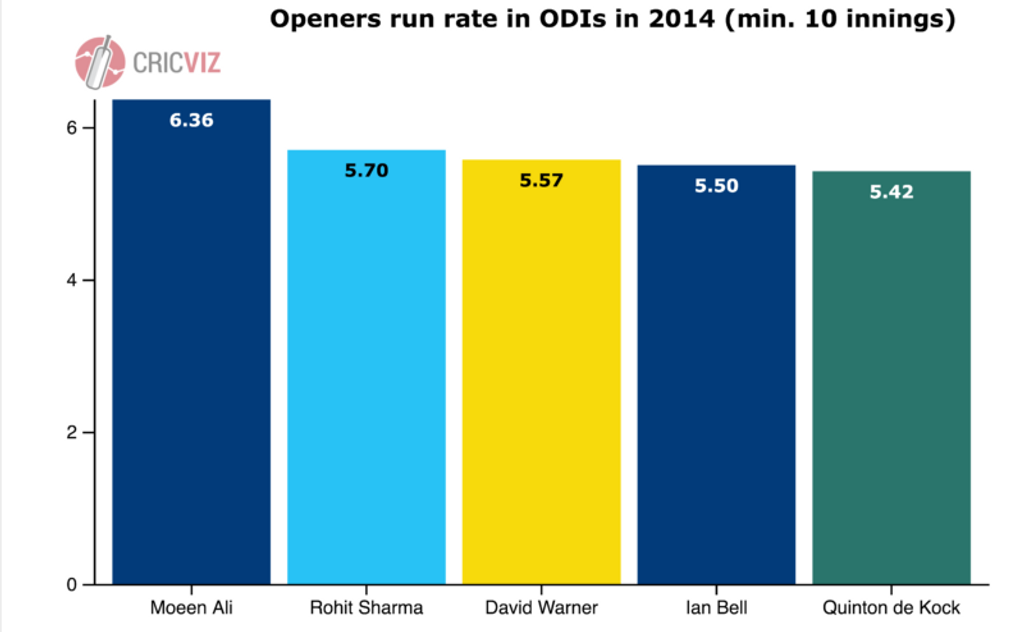

Despite that, something clearly wasn’t right and England recognised they had a problem with Cook at the top of the order. Belatedly, yes, but the decision to replace him before the World Cup meant that they were pairing Moeen Ali, who opened for all seven games on that Sri Lanka tour, alongside Ian Bell. In 2014, Moeen was the fastest scoring opener in ODI cricket, while Bell was fourth in the list, fractionally behind Australia’s David Warner.

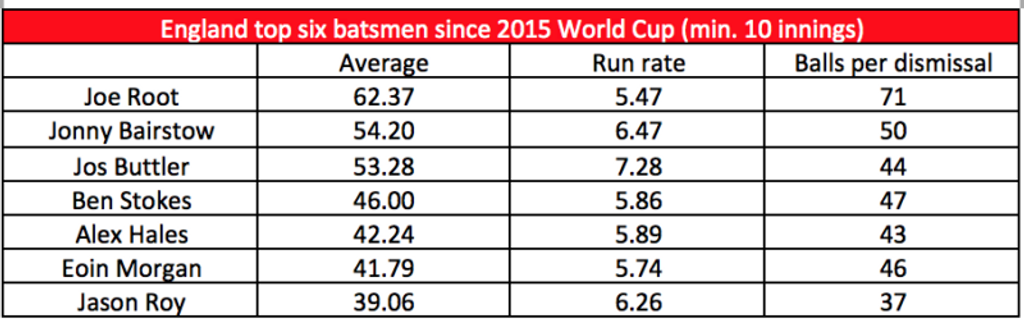

Clearly, England’s top order batting has improved enormously since Jason Roy was brought into the team, initially alongside Alex Hales and latterly with Jonny Bairstow. The improvements can be seen not through a change in mentality in terms of attacking shots, rather a greater success rate of execution of those shots, coupled with an ability to keep batting for longer.

As the table shows, despite England attacking less at the start of the innings, the current iteration have outperformed their 2014 counterparts in every metric available. It has been judicious, controlled aggression that has seen the likes of Roy, Hales and Bairstow succeed in England’s top order.

Solving the Stokes conundrum

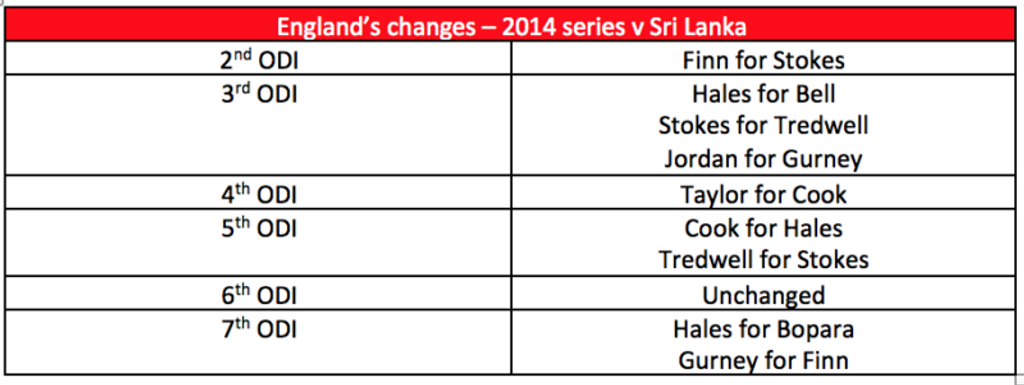

A more intangible aspect that has changed since the 2014 series is the clarity of players’ roles within the side. The current England team is a well-drilled, well-oiled machine in which at least eight of the 11 spots are occupied by players whose place is never in doubt. Back in 2014, England used 15 players across the seven matches and only named an unchanged line-up once. For instance, Alex Hales came in to the XI for the third match to bat at three, scored 27 before being moved to the top of the order for the next match – Cook was banned for a slow over-rate – where he bagged a golden duck and was promptly dropped for the next two games before returning in the final match at number three once again.

None of it pointed towards a side that knew its best XI or, perhaps more pertinently, knew how the 11 players should be performing.

No player embodies this stark contrast between eras better than Ben Stokes. England knew they had a precocious, talented all-rounder on their hands but seemingly had little idea of how best to use him. Admittedly, Stokes had come into the 2014 series off the back of a home series that had seen him register three ducks in as many innings in the Test series against India. However, that didn’t mean he was unable to hold a bat; it was the same player who had plundered 120 against the all-conquering Australia team on a decaying WACA pitch earlier that year.

Yet England were utilising him ostensibly as a bowling all-rounder, batting at No.8 and only being thrown the ball as a third, fourth or even fifth change. The series was a miserable one for Stokes: 22 runs from two innings while his eight overs with the ball conceded 85 runs with no wickets. It concluded something of an annus horribilis for him after his wretched summer with the bat had followed an ODI tour to the West Indies where he scored nine runs in three innings. He ultimately failed to make it into England’s World Cup squad and it speaks volumes that few people were surprised by his omission.

Since the World Cup, Stokes has batted 35 of his 42 ODI innings at No.5 and the other seven at No.6. His role is clearly defined as a middle-order batsman capable of bowling his full allocation of overs when required. Stokes’ improvement as a batsman has been well-documented but there is a chicken-and-egg-style debate to be had over how and why that has happened. England have given him licence to bat in the top five and he has repaid that faith, evolving into one of England’s key men with the bat.

Stokes’ rise to England’s premier batting all-rounder can be seen as a microcosm of England’s change in fortunes in the 50-over format. The turmoil and uncertainty that blighted both the aftermath of the tour and the series itself in 2014 have been replaced by a clarity of thought and an understanding of what direction the team is heading towards. England have never whitewashed Sri Lanka in an ODI series; they have surely never had a better opportunity than now.