Scott Oliver delves deep into the summer Adam Gilchrist tore up at Richmond CC, learning to drink big, dig ditches, and pile up the runs.

When Adam Craig Gilchrist sat down in December 1989 for his A-level equivalent HSC exams at Kadina High School in Lismore, a small town of around 25,000 people in northern New South Wales, he might have considered himself at a disadvantage – undercooked, in the local idiom – having been absent for the whole of Year 12’s middle two terms. Then again, given the vocation that had already by that stage started whispering softly in his ear, he may also have thought that spending five months in London playing for Richmond in the Middlesex County League (MCL) was the perfect education. A boy of seventeen when he arrived, a man of seventeen when he departed, it’s fair to say the polite, unassuming kid that had left New South Wales five months’ earlier got straight A’s for his summer’s work, contributing immensely to a season the club and his teammates will never forget.

Initially, though, recalls First XI captain Chris Goldie, they didn’t know what to expect, “to the extent that, after an underwhelming first weekend, I didn’t pick him for our penultimate Saturday friendly prior to the start of the league season. Graham Roope [the former Surrey and England batsman] had phoned me to say he was living locally and looking to join a local club. It’s the 17-year-old Australian who hasn’t scored any runs or the bloke with 20-odd Test caps, you know?”

However, on the Thursday that week, too late for weekend selection to be changed, Richmond played the first round of the Bertie Joel Cup, a competition entered by most of the top clubs of London and the Home Counties. Goldie wasn’t available, but kept abreast of the game against Metropolitan Police of the Surrey Championship from his office. “I remember ringing the bar phone at the club mid-afternoon to see how we were getting on. I spoke to our Second XI captain, Ricky Cameron, a West Indian, who was skippering on the day. His response was, ‘We are doing okay. The boy Gilchrist just got his ton and we’re 200 for 0’. Adam ended up with 159 not out that day.” He was up and running.

“On the Saturday, playing for the twos at Finchley,” Goldie continues, “he scored 113 not out – seven fours and five sixes – and finished the match before the last hour. On the Sunday, he scored 112 against a strong Wimbledon first team. By the end of May he had 996 runs for Richmond and had earned himself the nickname ‘Boy Wonder’.” Back home, Boy Wonder’s local newspaper, the Northern Star, ran the headline: Adam Gilchrist Terrorising the Poms. It wouldn’t be the last time.

Those 384 runs for once out in four days suggest he went pretty well with the bat in those early May matches, but Gilchrist – he of the 416 Test victims, second only to Mark Boucher – didn’t have the gloves. Not in the league, at least. Goldie had kept in the 1982 Benson & Hedges Cup for the Combined Universities side skippered by Derek Pringle and later spent three years at Hampshire. Plus, he was skipper.

Nor was he the only player with pedigree in the Richmond dressing room. Sitting on 90-odd not out against Met Police when Goldie rang was Michael Roseberry, who later scored over 10,000 first-class runs for Middlesex as opener. Also in the top four were Trevor Brown – who represented England Schoolboys and was offered a professional deal by Leicestershire only to have it withdrawn when he told them he was going to university – and Rupert Cox, who would play 19 first-class games for Hampshire between 1990 and ’94, scoring a Championship hundred against Worcestershire at New Road. There was Roope, too, albeit only for that pre-season friendly (in which he scored a ton) and the first league match (a duck), before he headed off to play for Preston in the Northern League.

The new ball was taken by Andrew ‘Animal’ Jones, who had played three first-class matches for Somerset four years earlier and was the hard-partying wingman to the previous season’s overseas, Dean Waugh (brother of), while the attack’s key man was 55-year-old left-arm spinner Peter Ray. Known as ‘The Penguin’ thanks to an uncanny resemblance to the actor Burgess Meredith from the cult 1960s Batman TV series, Ray was rated by Goldie as better than Phil Edmonds and Phil Tufnell, both of whom he’d seen at close quarters in the Middlesex League. The former Times and Telegraph cricket correspondent Michael Henderson rated him the best after-dinner speaker he ever heard, too. He was as “cantankerous and miserable” on the field, says Goldie, as he was gregarious off it, and he would finish, at 64, with a record number of top-flight MCL scalps and its all-time best figures of 10-57. In such company, Gilly’s stripes would have to be earned.

The Middlesex League was young – the same age as Gilchrist when he arrived in London – having emerged, belatedly, from a longstanding, and ongoing, tradition of competitive friendlies in the south east. It may have lacked the seasoned superstar pros of some of the venerable leagues further north, but it was unquestionably tough cricket – along with the Birmingham League, arguably the best in the country at the time – the standard beefed up by a steady flow of graduates gravitating to London to join the professions. It was exactly the sort of challenge envisaged by Gilchrist’s father when he paid Adam’s way across.

Richmond had only managed one top-half finish in the previous seven MCL seasons, with fourth – in 1976 and ’77 – their highest ever finish. Finchley had won six of those first 17 titles, with another five clubs bagging two. Among those were Enfield – the reigning national knockout champions, having seen off Wolverhampton the previous August – and Teddington, who lost the national final in 1987 to an Old Hill side featuring Dean and Ron Headley, but would win it in both 1989 and 1991.

When he wasn’t churning out those hundreds, Gilchrist spent some of the pre-season doing manual work, clearing the ancient ditches that separate Richmond’s Old Deer Park ground just south of the river (or east, given the Thames’ longitudinal course at those coordinates) from the Royal Botanic Gardens in Kew, a World Heritage Site whose 163-feet pagoda peers at the cricket over tall trees and the adjacent London Welsh rugby pitch, Richmond CC’s co-tenants since 1957 on a ground still owned by the Crown.

“It was called a ha-ha,” says Goldie, “a dry moat around old country estates to keep the livestock in without having a fence spoil the view for the Lord. Adam cleared it out with Big Albert Helg, a New Zealander who played rugby league, although I suspect Adam mainly stood around holding rakes. I’m not sure whether he was paid, but if he was it would be the only money he got off Richmond. We didn’t charge him subs or match fees, obviously, but that was about it.”

The league campaign – one game each against the other seventeen teams, an expansion of two from the previous year – finally got underway on May 13. It was timed cricket with no over limits, a continuation of the pre-league traditions, and clubs could decide whether they wanted to play all-day games (11.30 starts) or half-day (2pm starts). There were 10 points for a win, four for a winning draw, one for a losing draw, and none for a defeat. “As declaration matches,” says Goldie, “there were no restrictions on first innings overs so theoretically the side batting first could bat as long as they wanted. Losing the toss was not an advantage when playing a weaker side on a flat pitch!”

Richmond began with a draw at reigning champions South Hampstead, Gilchrist stumped off Sussex’s rookie off-spinner Bradleigh Donelan for 32. This dismissal was not a harbinger of the cavalier dasher of his later years, though, the first man to hit 100 sixes in Test cricket, a player who scored 260 runs (54, 57 and 149) in his three World Cup final wins off a combined 188 balls. “The thing that stood out was his maturity, both on the field and off,” remarks Trevor Brown. “He wasn’t then what he later became. He didn’t go in and smash the ball all over the park, although there were moments in friendlies and other cricket where you could see he could do it. He just had a big appetite for scoring huge amounts of runs and once he got in, he didn’t get out.”

Gilchrist made 93 on the Sunday in a friendly against Met Police, which was followed by the first of three straight league wins – against new additions Cockfosters – in which, opening the batting with Roseberry, he fell for just eight. But there was another Sunday ton against Beckenham, followed on Tuesday by 72 against Wimbledon in the Bertie Joel, setting up Gilchrist nicely for the visit of Brondesbury, alma mater of Mike Gatting, whose main threat was the former Indian Test left-arm spinner Dilip Doshi.

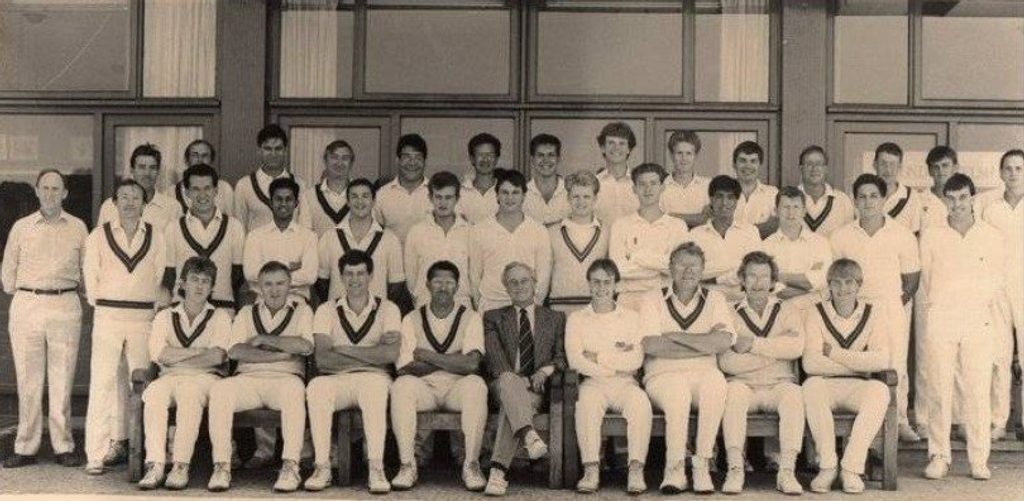

Richmond CC in 1989

Richmond CC in 1989

“They made 197,” recalls Goldie, “and we were without Roseberry, Cox and Brown. I told Adam, a lad of 17 who I hadn’t picked three weeks earlier and was about to face a still very, very good bowler: ‘You’re our senior player. If you bat through for a hundred, we’ll win’.” Doshi bowled unchanged from one end (22-5-53-2), but the Boy Wonder was up to it, compiling a masterful unbeaten 110 not out. He followed this with 150 not out on the Sunday against Surrey Championship side Old Emanuel. This wasn’t a young cricketer minded to give it away to allow teammates a hit.

An eight-wicket win at Stanmore, Angus Fraser’s club, consolidated Richmond’s early momentum, and Gilchrist’s run glut slid his feet firmly under the table and the rest of him out of the shadow – on the field, at least – of Dean Waugh, whose run-making and carousing had left such an impression at Richmond the previous year. In his autobiography, True Colours, Gilchrist looks back in anguish at the 17-year-old country boy’s attempts to adapt to an unfamiliar social environment as well as his 19-year-old city-boy predecessor had done. On the field, there was plenty to write home about – as indeed there was while continuing his HSC studies by correspondence – but his early season letters also expressed these teething troubles with the booze and bravado, second-guessing what he thought was expected of him:

“I wrote to Mum and Dad: ‘I really want to get some runs. I’d love to get 100 so that everyone might stop talking about Dean bloody Waugh. The big hero who drinks everyone in the club under the table. We’ll see how I go, eh?’ (My thoughts on Dean would change by the end of the trip … a fantastic bloke. My ability to drink a beer would also change.)”

Gilchrist was living in the Twickenham home of the somewhat bacchanalian chairman of Teddington CC, Michael Welch, along with a couple of other Australian cricketers: Tim MacMillan and Brad McNamara, the future head of Channel 9’s cricket coverage. It was an experience his book describes with some angst, the teenager often retreating up a pull-down wooden staircase to his loft room, ‘the Birdcage’, after being teased about his inability to hold his drink.

“In those early weeks I particularly dreaded the social occasions,” he goes on. “English cricket clubs set world’s best practice in putting away pints of warm beer, and Dean Waugh had left a few records in that department. He’d have been pleased to know I was no threat. We’d be in a pub after a game and I’d stand there and think: ‘Whatever they’re doing, I’ll do.’ But those beer glasses were so wide and so deep, and I’d never get to the bottom of them because someone would come around and, ‘Oops, it’s full again!’ I’d stand there all night and talk, then get home and throw up. I’d had alcohol before, but going to parties and skolling a drink or two was no kind of preparation for English-style socialising. I hated it. I’d come home, throw up and cry my eyes out. It wasn’t just the alcohol – it was feeling so alien to their culture, feeling that I wasn’t fitting in because I wasn’t drinking and kicking on through the night, wondering if there was something wrong with me because I couldn’t be one of the boys.”

Fortunately, Gilchrist also had his older brother, Dean, living a half-hour bus ride away in Ealing and playing in the Middlesex second tier for Old Actonians, for whose Under-17s Adam turned out (Richmond didn’t yet have a Colts team) in midweek 20-over matches, keeping the engine ticking. Unsurprisingly, given the presence of one of cricket’s greatest ever ringers, OA’s Under-17s won a league and cup double.

The brothers would spend a lot of time together that Ashes summer – a thumping 4-0 win for the tourists, with Mark Taylor scoring 839 runs, Terry Alderman taking 41 wickets, and England getting through 29 players. Adam joined OA’s on a tour of northern England, while the pair later headed off on a three-day road trip of the country, taking in Edinburgh, Loch Ness, Glasgow, the Lake District, Wales, Liverpool, Manchester and Nottingham, sleeping in the car and eating cheap food, the quintessential British experience for skint young Australians. Big bro helped him weather the culture shock – “without him I would have packed up and come home,” he wrote – and things soon settled down on the piss as they had on the pitch. “Gilly was able to participate socially,” says Brown, “but without going over the top. He learned when to duck out. He also managed to study for his A-levels in a party house. For a 17-year-old, he was massively impressive.”

On the field, Richmond went five mid-season MCL games without a win: four draws and abandonment. Gilchrist started this run with 67 in a see-saw game at Ealing, Richmond finishing on 234-9 in pursuit of 243, followed by 15 against Hampstead – the late-career home of Fred ‘The Demon’ Spofforth – bowled by the left-arm spin of Middlesex staffer Alex Barnett.

That same day, a mile south down the Finchley Road, three stops on the Jubilee Line, Steve Waugh, having made his first Test hundred in Leeds a fortnight earlier, was busy flaying 152 not out with the tail, Australian Prime Minister Bob Hawke watching on from the visitors’ dressing-room balcony as his compatriots eased toward a commanding 2-0 lead. At that stage, ‘Tugga’ was averaging infinity for the series, by the end of which it had only come down slightly to 126.5. Meanwhile, England skipper David Gower marched out of a hostile press conference that evening, telling his accusers he had tickets for the theatre (to watch Anything Goes). The well-mannered young Gilchrist didn’t brag too hard – after all, England had won three of the last four Ashes and were surely likely to turn things round; if not this time, then definitely at some point over, say, the next six or seven series – but he was seeing the real-time emergence of an Australian juggernaut he himself would later turbocharge.

A third draw came in Richmond’s cagey top-of-the-table clash with Teddington, whose opening bowler was Dawid Malan’s father, Dawid Malan. Teddington made 205-8 from 70 overs, ‘Penguin’ taking 6-50 from 22 overs, while Gilchrist was stumped for a duck in a chase that finished on 184-7 off 56. This was followed by an abandonment against Wembley and a losing draw at home to Shepherd’s Bush, Richmond hanging on at 99-9 (of which Gilchrist made 28) to preserve their unbeaten record. The five-game winless streak was finally ended by a thumping 107-run win over Uxbridge, Gilly chipping in with 32 against future Australian Test leg-spinner, Peter McIntyre, while Brown scored 92, one of seven half-centuries in a campaign yielding 630 runs at 63.

On the final Saturday in July – the day another stylish left-handed ‘keeper was fidgeting his way to an Ashes 128 up in ‘Madchester’, appropriately so with this being the second Summer of Love and RC Russell Esq. being fond of a Stone Roses-style bucket hat – Gilchrist made just 11 in a draw at Finchley. It was now six league games without a half-century for Boy Wonder.

Not that these middle months were a drought, exactly. There was 129 not out against North London in the Middlesex Cup, while those hard-boiled friendlies brought 144 not out against Horsham and 110 not out against East Molesey, Alec Stewart’s club. Two more Gilchrist tons adorned Richmond’s Cricket Week: 141 against The Stage and 102 against Pamplonian Flyers. Jazz-hat, maybe, but runs is runs. Still, while Gilly was never not in nick, Richmond were hoping that, with the coming of August and the sharp end of their pursuit of an elusive maiden MCL title, the 17-year-old prodigy would go gangbusters.

By this time, the burgeoning Gilchrist legend had even reached the BBC, who sent a local reporter down to Old Deer Park to interview the young batsman and his captain at midweek practice (unfortunately, there was no Internet or WhatsApp for him to send the link home to Goonellabah, Lismore). Saturday’s game against Winchmore Hill duly brought a four-wicket win, Boy Wonder’s 52 and 76 from Cox the backbone of Richmond’s chase, but the following week saw him dismissed for a single in a cagey losing draw with national club champions and erstwhile title rivals Enfield: 186-8 plays 115-5. “I was determined that we would not lose, so declared as late as possible,” says Goldie. “They took the winning draw, but I’m pretty sure it knocked them out of the title race.”

Four league matches remained. The first, against Brentham, Mike Brearley’s club, saw Gilchrist run out for 12, but 64 from Goldie secured a nervy three-wicket win. Next, as the final Ashes Test was being played out at the Oval, Gilchrist scored 55 in an abandoned game against a Hornsey team also still just about in the title race. The penultimate game was against lowly North Middlesex, who were skittled for 106 thanks to Peter Ray’s spell of 13-6-18-4. Gilchrist made 60 in the chase, falling to future New Zealand off-spinner Paul Wiseman with the game as good as won.

Going into the final game, then, away at third-placed Southgate, Richmond were joint-top with Teddington on 88 points, with Southgate just a couple of points back. All sorts of permutations were possible. Since they were ahead on the number of wins, seven to six, Richmond simply had to match any positive result Teddington achieved at bottom-placed Brondesbury (who had only one victory all year) to secure the title. Should Teddington manage only a losing draw, however, then matching it would not be enough, as this would necessarily mean a winning draw for Southgate, who would thus come up on the rails to snatch it. The winning draw was simply determined by scoring rate, so a team batting first could only pick up the four points if they bowled more overs in the second innings than they had received, something else that might enter the equation as the day unfolded.

The club was abuzz all week. Rumour has it Master Gilchrist would go on to play bigger games later in his career, but this was arguably the biggest so far. Richmond would go into it without their Penguin, however, whose second wife – “a Russian he met on the Metropolitan Line from Pinner into the City who could never quite cope with the cricket schedule,” says Goldie – had already booked holidays, unaware that September’s second Saturday was, unusually, a league fixture. “As Peter left the Richmond bar late the week before,” Goldie adds, “he declared that if we won the league in his absence, he would streak around Brondesbury’s ground when we travelled there the following Saturday for an end-of-season friendly. Given that leaving the visitors’ changing room at Bron in those days meant going through the bar, it was going to be something of a spectacle.”

Three days prior to the showdown, Teddington had won their maiden National Club Championship, beating Old Hill in a replay at Edgbaston to earn £1250 and a trip to Barbados courtesy of sponsors, Cockspur Rum. However, as word filtered through that their game against Brondesbury was not following the formbook, it appeared the euphoria and rum-fuelled celebrations had left them nursing something of a metaphorical, if not literal hangover.

At Southgate, meanwhile, the home team had been knocked over for 136 in 62 overs, recovering from 56-7, and Richmond had set about the chase. Gilchrist contributed what turned out to be a top-scoring 22 before being caught and bowled, all the while his captain was desperately trying to get current information on the Teddington game. These days, it would simply be a matter of following live updates fed directly from computerised score-boxes to a phone app. Back in 1989, it wasn’t so straightforward, recalls Goldie: “Mobile phones in those days were very much the preserve of the wealthy and the only person to have one in our side was Nick Morrill, who was, or is, a successful banker. He had one in his car and it was rumoured that the call rate was £1 per minute!”

By a coincidence of the fixtures, Richmond’s Third XI, ‘the Cronksquad,’ had played and won that day on Southgate’s second pitch, keeping them on course for their own title, and were now offering vocal support. Their colleagues had slipped to 115-6, though, top six all gone, a dismissed Goldie giving Brown what Boy Wonder might call “a spray” for failing to keep him posted on events at Bron and, amid the tension, Morrill off phone duties and at the crease in deteriorating light. Even so, the station was being manned and news arrived confirming that Brondesbury had turned Teddington over, meaning Southgate now had to take the final four wickets inside a couple of overs to deny Richmond the title. Six runs were needed from the final over, still four wickets in hand, but Goldie issued pragmatic instructions via the time-honoured hand-gesture and three dead-bats later the deal was sealed. At which point, bedlam.

Richmond had their maiden championship. At the end of a summer in which he’d scored 3821 runs, more than Bradman ever managed on these shores, Gilchrist threw himself manfully into the night’s revelries, and a week later, around the time Boy Wonder’s plane touched down in Brisbane, Peter Ray upheld his pledge to streak at Brondesbury.

BACK: Andy Jones, Nick Morrill, Jim White, Dave Harding-Smith, Jon Perry, Adam Gilchrist, Al Soni

BACK: Andy Jones, Nick Morrill, Jim White, Dave Harding-Smith, Jon Perry, Adam Gilchrist, Al Soni

FRONT: Peter Ray, Chris Goldie, Trevor Brown, John Woollhead

Back in Lismore, on the banks of Wilson’s River, a tributary of the Richmond, Gilchrist prepared for his exams, but found time to pen a loved-up letter to the club: “I have felt privileged to be associated with such a fine group of people and feel we were all rewarded for our hard work this year by finishing 1-2-1. I wish you all happiness in the future and hope that, within the next few years, I can return and be as accepted as I was this year. Maybe I’ll be as experienced off the field as the Penguin is on by then (crucial!).”

He did return for one further season of British club cricket, failing to register a competitive hundred as the paid man on the banks of the Tay at Perthshire CC’s North Inch ground, which had flooded in April and made life difficult for an emerging destroyer who was, by then, well into his long apprenticeship in state cricket. The destination, of course, was to become the ultimate game-changer – both micro and macro: individual matches and the sport as a whole, redefining the keeper’s role – a revolutionary counter-punching Test number seven who won his first 16 games in the baggy green.

Richmond landed the title again in 1998 and 2004, the year the first recipient of the Adam Gilchrist Scholarship arrived at the club, established to allow its eponymous sponsor to help young Australians from country backgrounds benefit from the type of experience he had enjoyed. “I still see those five months of 1989 as the most influential time in my development,” he wrote in 2008, “really the end of my childhood, my coming of age, both as a cricketer and a person: learning how to be independent, fending for myself, cooking for myself. (Mum had given me a book of recipes and I did a mean potato fritter!).”

The 20-year reunion of Richmond CC’s first title winners

The 20-year reunion of Richmond CC’s first title winners

In 2009, Goldie’s champion team held a twenty-year reunion. Boy Wonder was there, albeit now on the cusp of middle age, a decorated and universally admired superstar who played fair and always batted selflessly, doing so now off the international treadmill while seeing out his playing days on the Twenty20 circuit. Thus it was that the following summer, during a short stint in the Blast, he completed the circle, skippering Middlesex against Glamorgan at Old Deer Park. Opening the batting with David Warner, he smote 51 off 31 balls, with three sixes launched somewhere in the direction of the ha-ha he had cleared all those years ago.

Adam Gilchrist hitting out on his return to Richmond CC while playing for Middlesex

Adam Gilchrist hitting out on his return to Richmond CC while playing for Middlesex

“It’s the only section of it that remains,” says Goldie. “We’re thinking of having it restored. If we do, we should probably have a blue plaque put up: This ha-ha was cleared by Australian Test cricketer– … No, the clearing of this ha-ha was supervised by Adam Gilchrist in 1989.”