In 1968 county cricket welcomed the world’s greatest players through its doors by relaxing the rules on residential qualification. Jon Hotten tells the story of a transformative half-century for the English domestic game.

This article is taken from issue 7 of Wisden Cricket Monthly, featuring a 21-page special to mark the 50th anniversary of overseas players in county cricket

It began the summer after the Summer of Love. The Advisory County Cricket Committee weren’t, as far as we know, the kind of guys to wear flowers in their hair, but they offered the game its moment of profound cultural change when they agreed to Nottinghamshire’s proposal that the rules governing overseas professionals be relaxed, with each county in the Championship competition allowed to appoint one. And just as, decades later, the inauguration of the IPL would be inured to failure by an indelible moment – Brendon McCullum’s opening night 158 – so the sport’s premier property, Garry Sobers, delivered one.

On August 31, 1968 at Swansea, Sobers hit Malcolm Nash for six sixes in an over, and in so doing condemned the 23-year-old left-armer to a lifetime of quiz-questionery. It was a totemic afternoon, still remembered as one that dragged county cricket into its new, Technicolor age.

***

Nottinghamshire had secured Sobers with an offer burnished by the same glamour as the IPL auction: an annual salary of £7,000, an apartment and a car, and, in return, he stepped into a Britain that smouldered with post-war austerity. Harry Pearson offered some vivid lines on+ the Championship as it had stood in 1967 in this year’s Wisden Almanack: “Even on the sunniest days, the game was played with a sense of impending chill; every batsman seemed to have a dewdrop forming on the end of his nose,” he wrote. “The cricket was dour and attritional, victories ground out with all the grace of Ray Illingworth chewing a day-old chunk of gum…”

Overseas players were not unknown in this bleak landscape. Some, like Roy Marshall at Hampshire, Warwickshire’s Khalid Ibadulla and Keith Boyce at Essex, negotiated complex rules regarding residential qualification, while league cricket was a reliable source of employment during months when there was little played anywhere else in the world.

Gordon Greenidge and Barry Richards of Hampshire walk out to bat for Hampshire in 1973

Gordon Greenidge and Barry Richards of Hampshire walk out to bat for Hampshire in 1973

Stephen Chalke, the historian and writer, identifies four phases of overseas players in England:

– “The period before the First World War when there was quite a row about the importation of ‘colonial cricketers’, with attempts to tighten the residential qualification. For the first time, some counties were prioritising the winning of the Championship above the idea that they were picking teams to represent the cricket of their county.”

– “The 1950s and early 1960s when the rise of immigration from the Commonwealth led to a number of overseas players settling here.”

– “The period from 1968 when counties could employ overseas players without any residential qualification; many of the best players in the world joined counties and played for them for many years.”

– “The modern era when the overseas players dip in and out, with little loyalty to one county, fitting in a few games between commitments overseas.”

Alongside Sobers came the cream of world cricket, great players beginning associations with counties that would run deep, both emotionally and physically

Of these, it is the third, beginning in ’68, that would become the most transformative. Alongside Sobers came the cream of world cricket, great players beginning associations with counties that would run deep, both emotionally and physically, nailing their names into the history of the English domestic game.

Here, two more shaping factors, unconnected and unpredictable, should be acknowledged: the first was South Africa’s exclusion from international competition, which began in the autumn of 1968 and meant that a generation of players, Barry Richards and Mike Procter at their forefront, would find county cricket both their solace and their stage; and the second being the extraordinary proliferation of West Indian talent that coincided with their rise under Clive Lloyd. Not only would the greats of their Test team, beginning with Rohan Kanhai, Lloyd and Alvin Kallicharran and on through Richards, Roberts, Garner and Holding, enrich life here, so would some formidable cricketers that could barely get a game in the national side. Sylvester Clarke, who took almost a thousand first-class wickets at less than 20 and who once won the Walter Lawrence Trophy for the season’s fastest hundred, played 11 Tests; Wayne Daniel, Middlesex’s Diamond, who took 867 wickets at 22.47 each, played just 10.

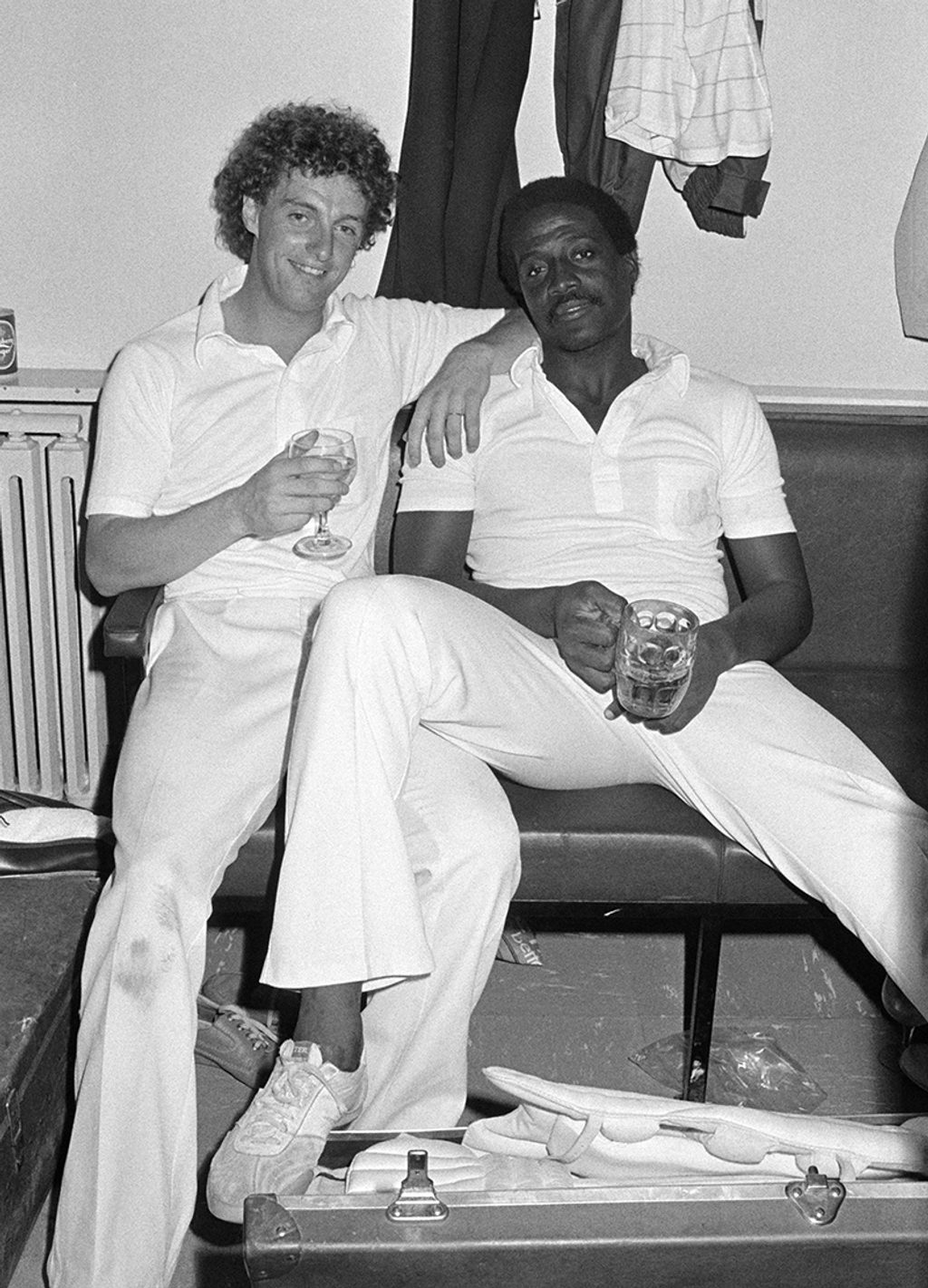

Sylvester Clarke relaxes with a drink alongside Surrey teammate Jack Richards

Sylvester Clarke relaxes with a drink alongside Surrey teammate Jack Richards

To be a batsman during these years, especially an opening batsman, was to encounter horrifying and ruthless greatness as a part of the day job. To Daniel and Clarke, Holding, Garner and Roberts, add Richard Hadlee and Clive Rice at Nottinghamshire, Malcolm Marshall at Hampshire, Imran Khan and Garth Le Roux at Sussex, Wasim Akram at Lancashire, Waqar Younis at Glamorgan and Surrey, Courtney Walsh at Gloucestershire, Allan Donald at Warwickshire, and so on. It’s no surprise that Geoffrey Boycott and others of his generation regard their first-class runs as highly as many of their international scores.

The Championship threw together gods and men, and allowed them to contextualise one another: Viv Richards alongside Colin Dredge, Andy Roberts in tandem with Nigel Cowley, Imran Khan and John Barclay. It could be incongruous, and maybe unfair if a humiliation were handed out, but it was democratic in its way. The fields of England held all of the game within them: all of its possibilities, all of its promise, all of its quotidian successes and failures. Anyone could go and see it close up. You could observe, often from a chair on the boundary rope, what cricket actually was; this game of individual struggle in a team context; the way it gave every player their moment; how it allowed huge disparities in size and shape and ability to fight it out.

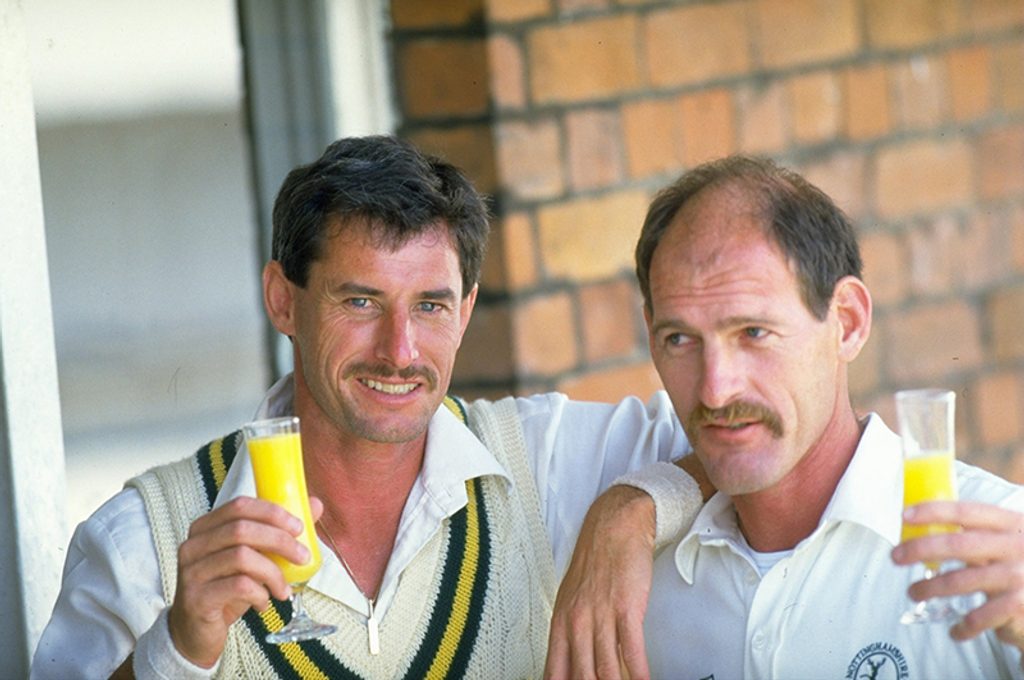

Mike Procter and Garry Sobers

Mike Procter and Garry Sobers

To a kid like me it seemed like a vast travelling circus, impossibly exotic and yet completely approachable. If I close my eyes and picture the scenes I can remember a trip to Hove, sitting side-on to the wicket and watching Imran Khan and Garth Le Roux take it in turns to charge down the hill, close enough to feel the visceral thrill of it; seeing Alvin Kallicharran, a tiny man, bat at Basingstoke, during a school trip on a grey day and watching in awe as he powered the ball over the hedge, out of the ground and into the road at the far end; watching Malcolm Marshall, also at Basingstoke, talking to the crowd between overs and coming in off a great curving run that seemed to stretch almost to the boundary; seeing Somerset win the Benson and Hedges Cup from the old Tavern at Lord’s, when King Viv made another inevitable hundred…

Of all of those players, none except my childhood hero Barry Richards gripped the imagination like Sylvester Clarke, Surrey’s star-crossed and doomed fast bowler. Marshall, although impossibly quick, was always smiling and joking with the other players. Joel Garner, in his post-match interviews and jigging wicket celebrations, seemed ridiculously nice. Imran was like a movie star, too Hollywood for real life. Hadlee would often chop his run down and cut the ball around to deadly effect. But Sylvester…

This was the power of the overseas pro. They became the stars of the county narrative, stories to be followed as the season ran its course

Ian Botham was once assigned to drink with ‘Silvers’ during a rain-break at Weston-super-Mare to ensure that Clarke had a hangover when he was due to bowl, one of the few ways of tempering his intent. He inculcated fear and trailed devastation: Steve Waugh said he felt the will of some of his Somerset teammates “disintegrating” in the days before their appointment with him; David Gower had most of his glove and part of his thumbnail torn off and sent spinning towards gully; John Emburey was caught at third-man simply fending the ball away; Simon Hughes wrote that “two millimetres of man-made fibre” separated him from death after Clarke struck him on the helmet; Graham Gooch’s lid was split down the middle; Dennis Amiss identified what he named Clarke’s “trapdoor ball” that followed the right-handed batsman on the trajectory of his throat.

Once I’d seen Sylvester bowl, I’d watch his progress in the papers, and whenever someone got runs against him I’d wonder how they did it. This was the power of the overseas pro. They became the stars of the county narrative, stories to be followed as the season ran its course. Their characters became a part of the character of the teams that they represented. Mike Procter was so key to the upswing in fortunes at Gloucester that fans began referring to the team as ‘Proctershire’. Richards and Garner, along with Botham, conjured carnival summers at Taunton, heady days of cup finals and good-natured pitch invasions. Peter Roebuck illuminated how it was to share a dressing room with such men in his book It Never Rains, the thrill of being pulled along by the momentum they created. It would end shatteringly a few years later when Roebuck, by then captain, and his supporters tried to arrest Somerset’s slide by not renewing the contracts of their overseas stars. Botham walked out in solidarity, and the schism it created was one of the few times when county cricket made the evening news.

***

For the new player, England could be a dislocating experience. In the gilded world of Premier League football, clubs employ people specifically to smooth the path of moving their million-dollar assets to another country: the star player need not feel the friction (there’s an apocryphal story of one young talent complaining to his fixer that he woke up every morning with damp pillows – it turned out he’d been sleeping with the window open). For the early overseas pro, it might have been left to a kindly landlady – South African Lee Irvine lodged with a good-hearted Chingford couple named Ron and Gladys Mouldey, who charged him £1 a week for bed and board – or to the wider diaspora.

Yorkshire were the final county to let go of their self-imposed residential qualification and so the player that came along had to be special. Sachin Tendulkar’s arrival was brokered by Solly Adam, a sports shop owner who had moved to Dewsbury from India as a child in 1963. Tendulkar was 19 years old, lodged at 34 Wakefield Crescent, Dewsbury, and drove around in a tiny Honda with his name painted on the side. On debut he scored 86 against a rampaging Malcolm Marshall before being run out at the non-striker’s end. “I always make a hundred in my first match,” he said gloomily. Yet it was to be a summer of joy and self-discovery, a time Tendulkar would call “one of the greatest four-and- a-half months I have spent”. His girlfriend, later wife, Anjali would drive over from Gloucester to see him, and he discovered the simple joys of KFC: “We would go up to Leeds for Kentucky Fried Chicken,” said Solly. “For some reason he loved it…”

Richard Hadlee and Clive Rice of Nottinghamshire

Richard Hadlee and Clive Rice of Nottinghamshire

Over the span of Tendulkar’s career, the system, like the game, changed shape, accelerating into its new culture. The notion of a county contract became something different, a short-term hop separated by a flight in and a flight back out again. Marcus North and Imran Tahir have each represented a third of the 18 first-class counties. The legend can still make an impact, but it tends now to be at the end of their career – Warne at Hampshire, for example, or Sangakkara, transcendent at Surrey.

The future, with its fractured calendar, offers only more of the same. Along with the gimmicks of new scoreboards and 10-ball overs, the ECB’s ‘The Hundred’ format must surely follow the path of creating its own heroes, because they are what we remember of the decades that 1968 began. Peter Roebuck titled his history of Somerset From Sammy To Jimmy, Sammy being Sammy Woods, the great Australian of the Victorian era who made Taunton his home, and Jimmy being Jimmy Cook, a still largely unheralded South African opener who cracked 28 hundreds in three seasons at Somerset, and set the West Country ablaze. Cook joined the list of players whose understated excellence wove them into the thread of the English game, a joy that the old-school summer offered everyone from Basher Hassan to Murray Goodwin.