Since he last played Test cricket in the 2019 Ashes, Craig Overton has dominated in the shires. CricViz analyst Ben Jones takes a close look at the evolution of a seamer who could make his international return next month.

On Tuesday, Chris Silverwood announced the first England Test squad of the home summer, for the two-match series against New Zealand. When it came to new faces, they were few and far between, with James Bracey and Ollie Robinson the only uncapped players in the squad.

One notable selection – albeit of a capped player – was that of Somerset seamer Craig Overton. The leading English wicket-taker in domestic first-class cricket since the start of the Bob Willis Trophy, Overton has done an impressive job of banging the door down and demanding to be selected.

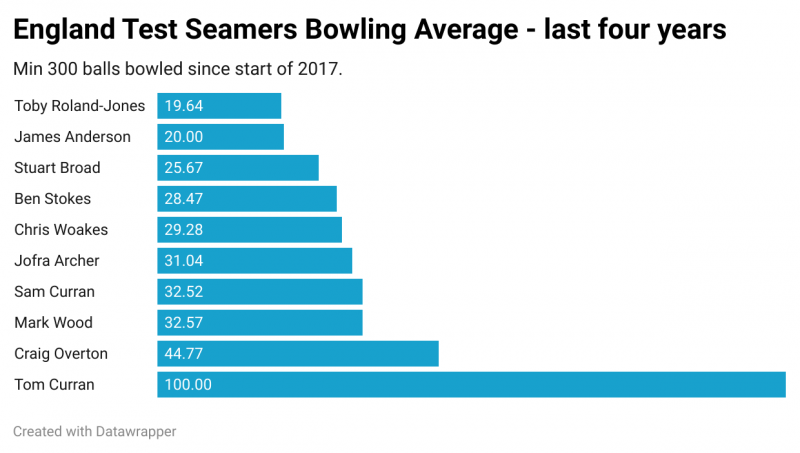

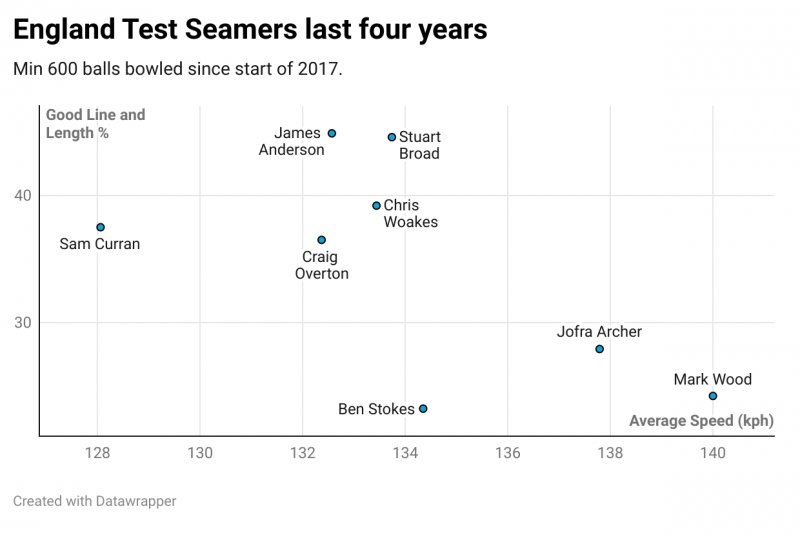

However, to date Overton has struggled quite significantly in Test cricket. On debut during the 2017/18 Ashes, he took six wickets in two matches before a cracked rib saw him miss the Boxing Day Test in Melbourne. Two isolated Tests since then – in Auckland and Manchester, 18 months apart – have brought similarly underwhelming results. Alongside other fast bowlers to play for England under Joe Root’s captaincy, Overton’s record does not stand up – his bowling average in Test cricket (44.77) is the worst for any England seamer across the last four years, barring Tom Curran who has only played two matches.

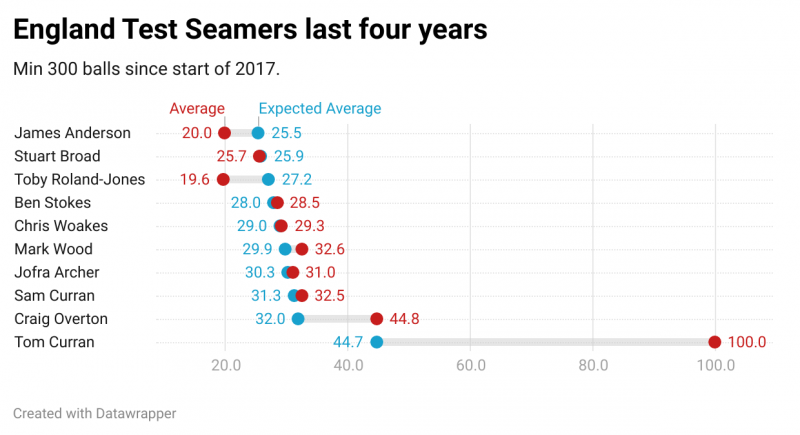

In fairness to Overton, there’s an argument that he’s been unfortunate with that record. His Expected Average – calculated using ball-tracking data for the actual deliveries he’s bowled – suggests that typically, Overton’s body of work in Test cricket would average 32, a clear distance from his ‘actual’ average. Yet even with that taken into consideration, his Expected Average still stands as the worst of the bunch except for Curran. So far in Test cricket, Overton’s not been good enough.

That initial stint at international level has seen Overton become something of a ‘yo-yo player’ – dominant at county level but not yet able to crack the top level; alternating as differently sized fish in differently sized ponds.

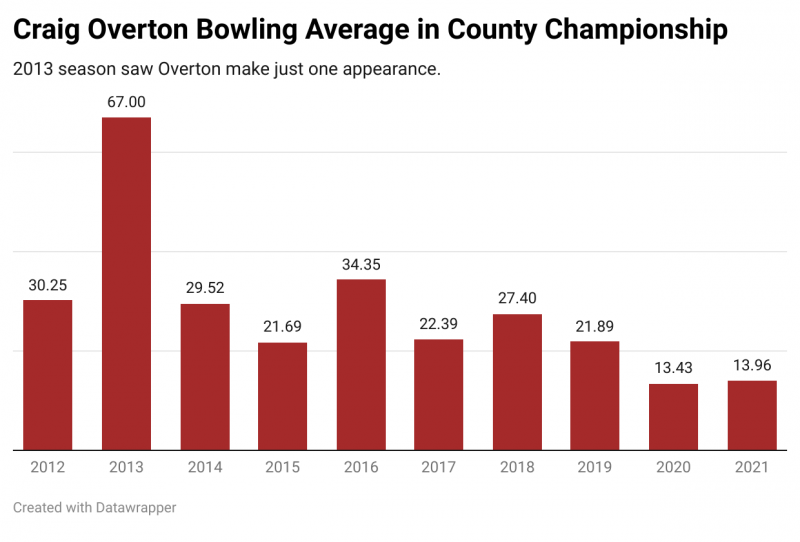

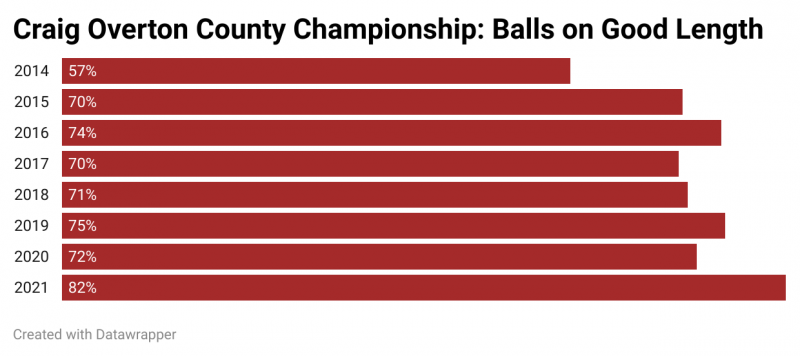

Yet while Overton has always done well in county cricket, his last two summers have taken things to a different level – he is averaging less than 14 with the ball since the start of the 2020 county season. When you send a player back to county cricket, you want to see improvement – Overton’s step up from very good to excellent is plain to see.

*2020 numbers refer to Bob Willis Trophy

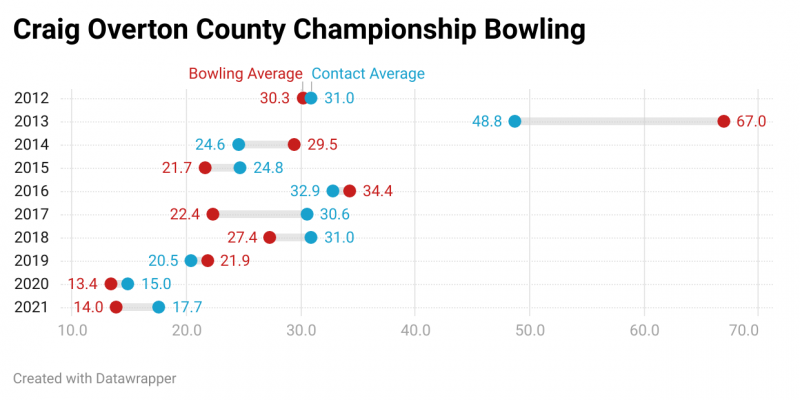

There’s evidence that Overton was overpromoted during his initial stint in the Test side. According to our Contact Average measure – which looks more closely at the connection bowlers are drawing from the bat, and rewards or penalises them accordingly (e.g runs scored from middled shots are given heavier weighting, while nicks through the slips are given less) – his Somerset performances in 2017 and 2018 were not as strong as the scorecard made them appear; his Test struggles were, realistically, to be expected. However, that criticism comes with an encouraging chaser – his recent county dominance is the real deal. That same Contact Average measure suggests that Overton’s excellent bowling average since the start of last season is entirely reflective of his performances.

*2020 numbers refer to the Bob Willis Trophy

A cynical observer may choose to focus on how Overton’s improvement coincides directly with the change in domestic tournament structure, which pits Division One and Division Two sides against each other, and that he’s simply bowling to worse batsmen than before. There’s certainly some merit to this reading: almost half (5/11) of Overton’s games in the last two seasons have been against counties who, all things being normal, would have spent 2020 in Division Two. Those matches have seen him take 33 wickets, at an average of 12. The opportunity to bowl at weaker players has clearly boosted Overton’s figures, to a certain degree.

This speaks to one of the issues with bowlers and yo-yo players like Overton – when everyone expects you to dominate county cricket, getting noticed for doing so is hard. It’s too easy for outsiders to write your excellence off, to label it more of the same and move on. Brilliant statistical performances like the ones Overton has been churning out are all well and good, but if that’s what they did last time, before falling short in Test cricket, why should we pay attention now?

You have to demonstrate growth, to make it clear you’re not just better than before, but that you’re different – new and improved.

As a yo-yo batsman, the easiest way to get attention and earn yourself something of a clean slate is to change your technique, adopt a radical new method (see Sibley, Lawrence) and one season of dominance is often enough. As a seamer, the key is the elusive claim to have Put On A Yard™. Given the relatively few people who watch red-ball county cricket live, the opportunity for rumours around a player to grow is ample. A quick bouncer becomes a quick spell, a quick spell becomes a quick match, a quick match becomes typical – “He’s really put on that extra bit of pace over the winter”. It’s no surprise that Overton has been the latest beneficiary of this process – a seamer leaving the England bubble as an 83mph seamer before tearing up the domestic tournament is almost the perfect candidate for the phenomenon.

We can’t verify the claims that Overton has increased his speed since last playing for England, given the absence of either ball-tracking or speed gun data at non-televised domestic cricket. The truth or otherwise of that statement will only be apparent when Overton sends down his first delivery in Test cricket, and not a moment sooner.

However, Overton’s method may have changed in an altogether more subtle manner. From data recorded by on-site county analysts, we can see an increase this season in Overton’s ability to find a good length. While line is not recorded, there is evidence that his improved bowling returns are as much about increasing control as they are increasing ball speed. This bodes well.

*2020 numbers refer to the Bob Willis Trophy

In some respects Overton has been unlucky. Having dominated the County Championship as part of one of the best sides in the country, four Tests in five years feels like a lack of opportunity. Yet in others, Overton has been very fortunate indeed. In 2015 Overton was heard telling Ashar Zaidi, a Pakistan-born all-rounder playing at the time for Sussex, to “Go back to your own f***ing country” during a County Championship fixture. Instead of the anticipated Level 3 charge that would typically accompany that sort of conduct, Overton was charged with only a Level 1 offence, the subsequent two-game ban a consequence of accumulated charges. He has since gone on to play Test and ODI cricket, with no apparent indication that the incident has harmed his international chances. Some might say that this is a man who’s been very lucky indeed.

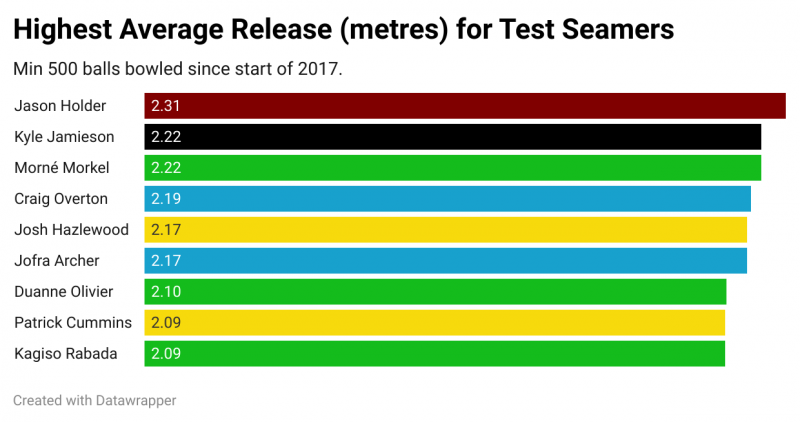

But now he’s in the squad, Overton is working from a position of strength. His raw materials, in terms of height and accuracy, interest England greatly. His average release height in Test cricket (2.2 metres from the ground) is the highest for any England seamer in the last five years, and the fourth highest of anyone in the world. That high angle may have suggested greater pace, but the angle matched with increased accuracy has potential – as Jason Holder can attest.

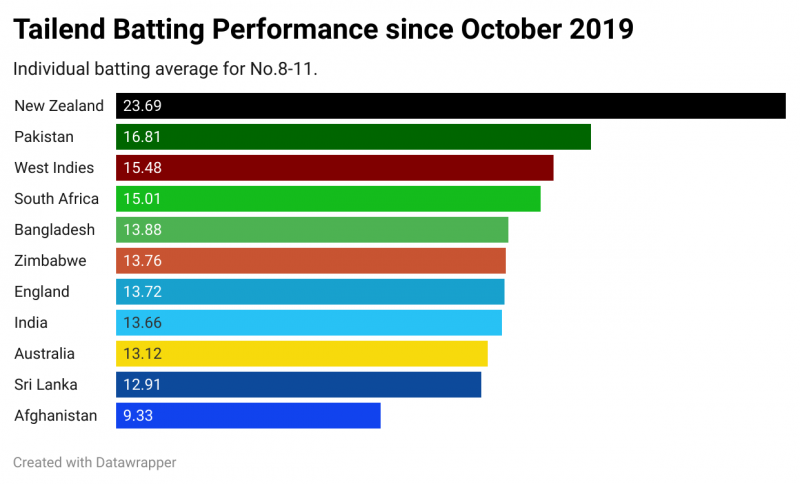

Equally, as with fellow Somerset graduate Dom Bess, Overton offers more than just his bowling. The all-round ‘package’ makes him a more appealing selection than if judged solely on his primary skill. Overton’s batting average since the start of the BWT is 32.78, would make him the 26th best batsman in the county by batting average alone (of those to play as often as Overton himself), and while his technique errs towards effective rather than aesthetic, at this moment England will more than happily take that. Since Chris Silverwood took over from Trevor Bayliss, England’s tail has stopped making runs, with just one half-century in 102 innings. For some, that’s a price worth paying if it coincides with the best four bowlers being selected purely on bowling merit, but Overton – in his current guise, and form – may allow the England camp to have their cake and eat it.

Equally, England’s particular approach to handling pandemic-induced welfare issues, as well as long-standing workload saturation, plays right into Overton’s hands. The importance of England’s rotation policy being executed properly that relies on players – bowlers in particular – having clear and well-defined roles. The experienced swing and seamers (Broad, Anderson, Woakes), the high pace attack-dogs (Wood, Archer, Stone), and the bowl-dry high-release workhorses (Overton, Robinson). Rather than having to fight his way through the pack, to be fourth or fifth in the fast-bowling hierarchy, Overton’s distinct skill set means he should stand a greater chance of playing three or four Tests in upcoming series.

Ultimately, Overton is in a good position. While his improved record can’t yet be ascribed to an increase in pace, it could well be an increase in accuracy, which is just as likely to aid his performance in the Test arena. In form, in bowling-friendly conditions, at his apparent peak, Overton is ready to return – whether he’s now good enough to succeed, we’ll find out soon enough.