Ben Jones analyses an astonishing passage of play on the fourth day of the second Ashes Test at Lord’s.

Ben Jones is an analyst at CricViz.

Today was about two men. Jofra Archer, a shyly ambling young man who, it seems, is yet to understand the full extent of his powers. Steve Smith, the greatest since the greatest, on a mission to return the urn to Australia for the first time since he was 12 years old, a childhood dream fulfilled. The classically perfect bowler, the unorthodox world-beating batsman; the racehorse, the shire horse; the genius, the genius.

The stage was set, the other players merely extras. This, this right here, was what we came to see.

***

Australia came out after lunch, 155-5, and Archer started his spell. Nobody knew what was coming up. Nobody was braced for what was about to happen. Cricket gives few clues.

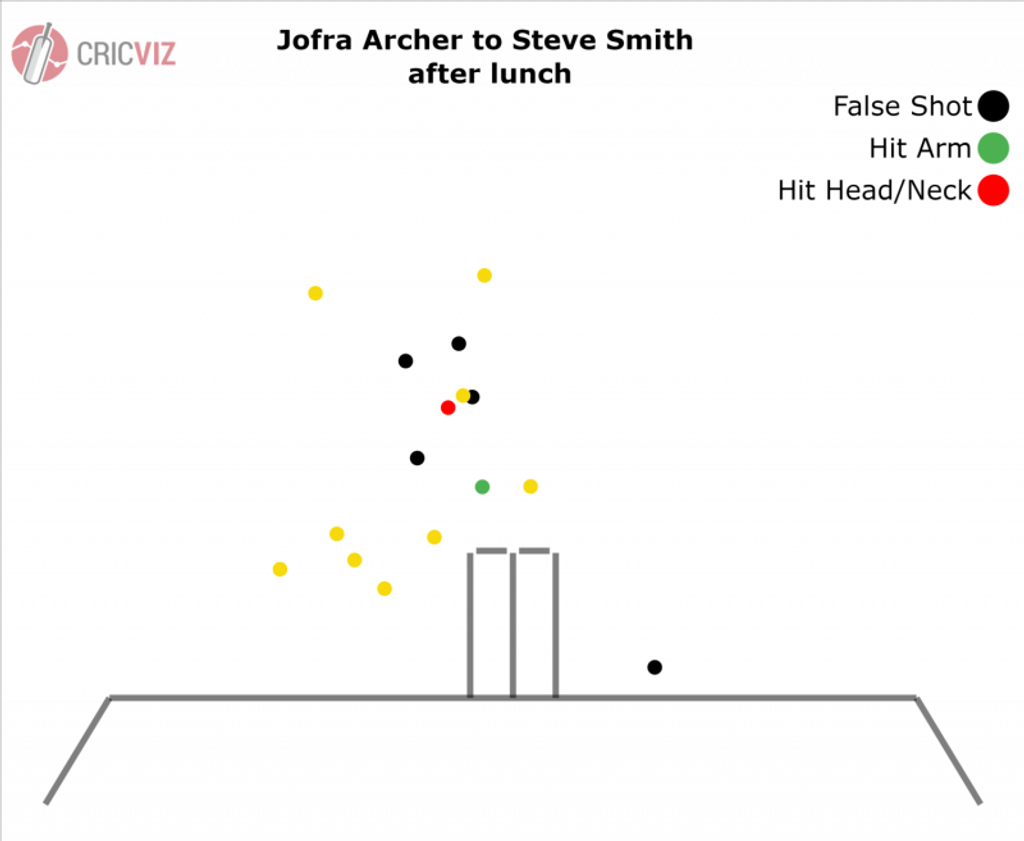

At first, it was subtle. Archer had Smith jumping a bit – that’s notable, in itself, for the rarity of it if nothing else. Balls were missing the middle of a bat that can often seem a metre wide, sometimes missing the bat altogether. There was a rising sense of anticipation. Something was happening, something was in the air.

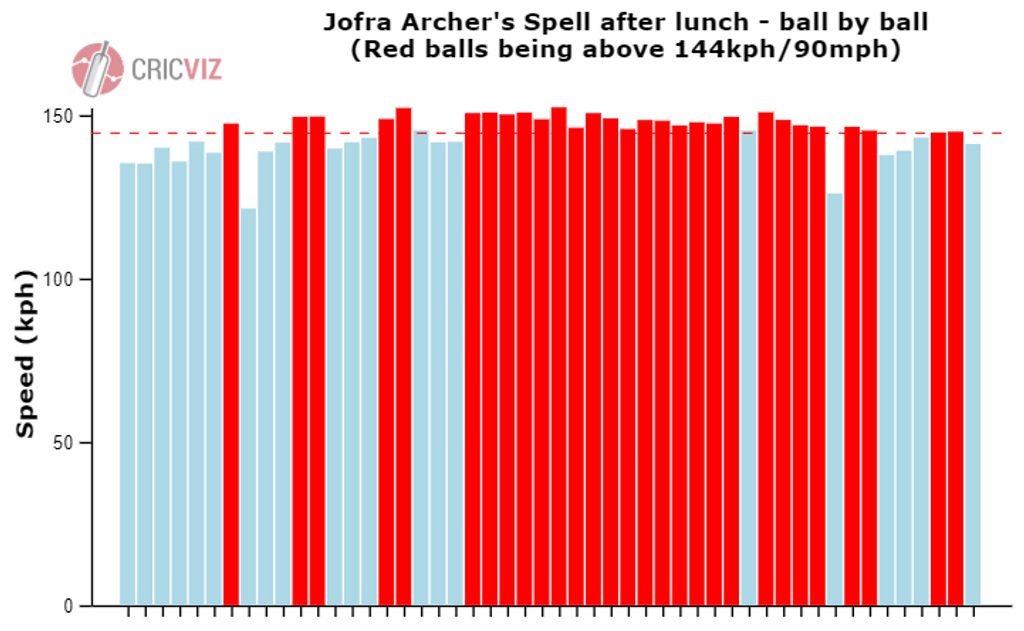

Eyes started to turn to the speed gun. 90mph. 92mph. 95mph. The numbers that the television graphics were throwing out, the figures being shown on the scoreboard in the ground, are the sort English fans are used to seeing when their side are batting, not bowling. Once a generation, they get a bowler capable of hitting those speeds – a Flintoff, a Harmison, a Finn, a Wood – but never with the certainty and swagger of Archer, never with the confidence that what was happening was not a flash in the pan. Never has England been so sure that this guy, this guy, he’s for real.

And, facing that, Smith was hooking. He does do that, against such bowling; 45 per cent of his shots to balls pitching 10m or shorter, are either hooks or pulls. But to do it to a man visibly so pumped, so obviously harnessing the swirling excitement of a crowd, to keep taking him on knowing that your wicket is the key to the game, to gamble the game with every horizontal stroke, with every high handed swoop across the line? At times, it feels as if Steve Smith is a different creature to the rest of us. Outside of Australia, Smith has almost never faced a quicker spell. Morne Morkel averaged 147kph against Smith in February 2014 – but that’s it. This was the greatest Test batsman of the modern era facing one of the toughest tests he’s ever faced. And he was going after it.

The 71st over was the first in which the drama crystallised into a single, discernible moment of clarity, as Archer struck Smith on the arm with a vicious, lifting delivery. When he’s set, that doesn’t happen to Smith. It was just the ninth time in his Test career that he’s been hit having faced more than 100 balls. In seconds it had swollen up almost to the size of the ball that caused it. A warning.

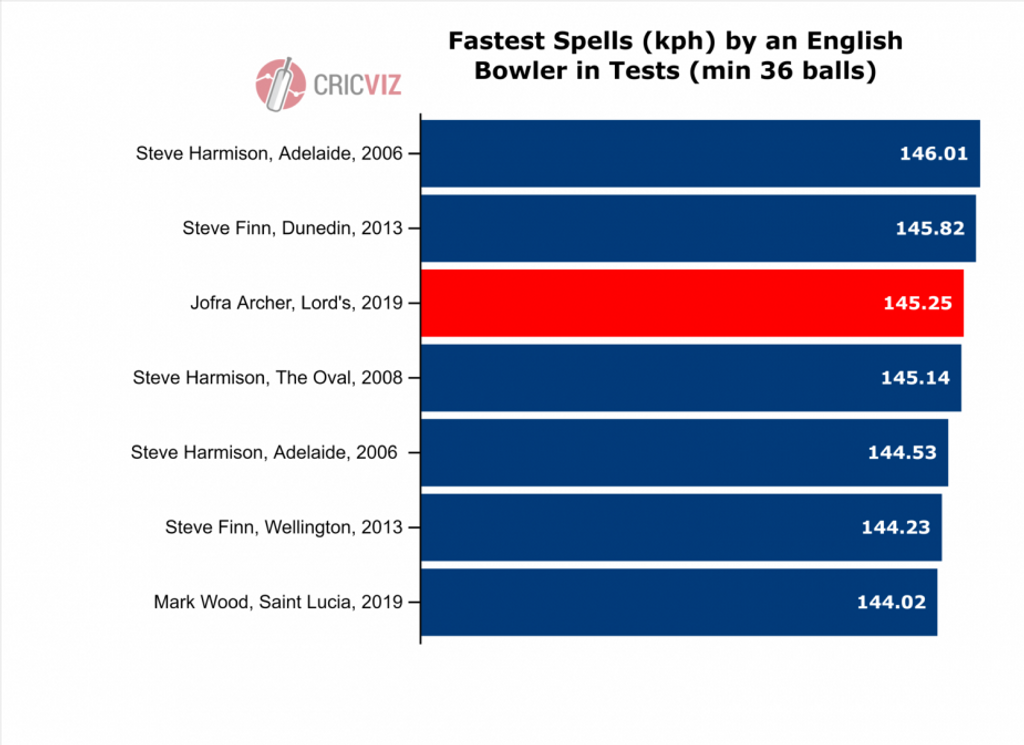

Then in the next over, Archer stamped his youthful authority onto English cricket’s history, and demanded that all the talk of white-ball specialists and stamina was put to bed as he hit his peak in terms of raw speed. The average speed – 92.79mph – made it the fastest over by an Englishman in Tests, where data is available. Nobody has stood at the top of their mark, the three lions on their chest, and sent down a faster over with a red ball.

It was remarkable. This was a man on Test debut, a child in international terms, charging in like a seasoned veteran, like an experienced member of the elite. It was the third-fastest spell by an England bowler (excluding slower balls), for when that information is available.

It’s a minuscule sample size, of course, but Archer has rattled the best. He has forced him into a false shot with 29 per cent of his deliveries; nobody to bowl more than 10 balls at Smith can say they have done better. This is a man who averaged over 90 against the short ball in the last three years, a man more than capable of dealing with the best. It’s a record which will fall away, undoubtedly, but against a man of Smith’s genius, even brief dominance is remarkable.

At one point, Archer bowled 16 deliveries in a row that were all over 90mph, the momentum gathering, the temperature rising. You could feel the ink being stroked into the history books, the words being written onto the page, It was a firework flying higher, higher into the sky.

Then it exploded.

Steve Smith doesn’t get hit. Trent Boult, in 2015; Neil Wagner, in 2016; Ben Stokes, last week. He has faced 11758 balls in Test cricket, and those are the three times that a bowler has hit him on the head/neck. The three times before today, that is.

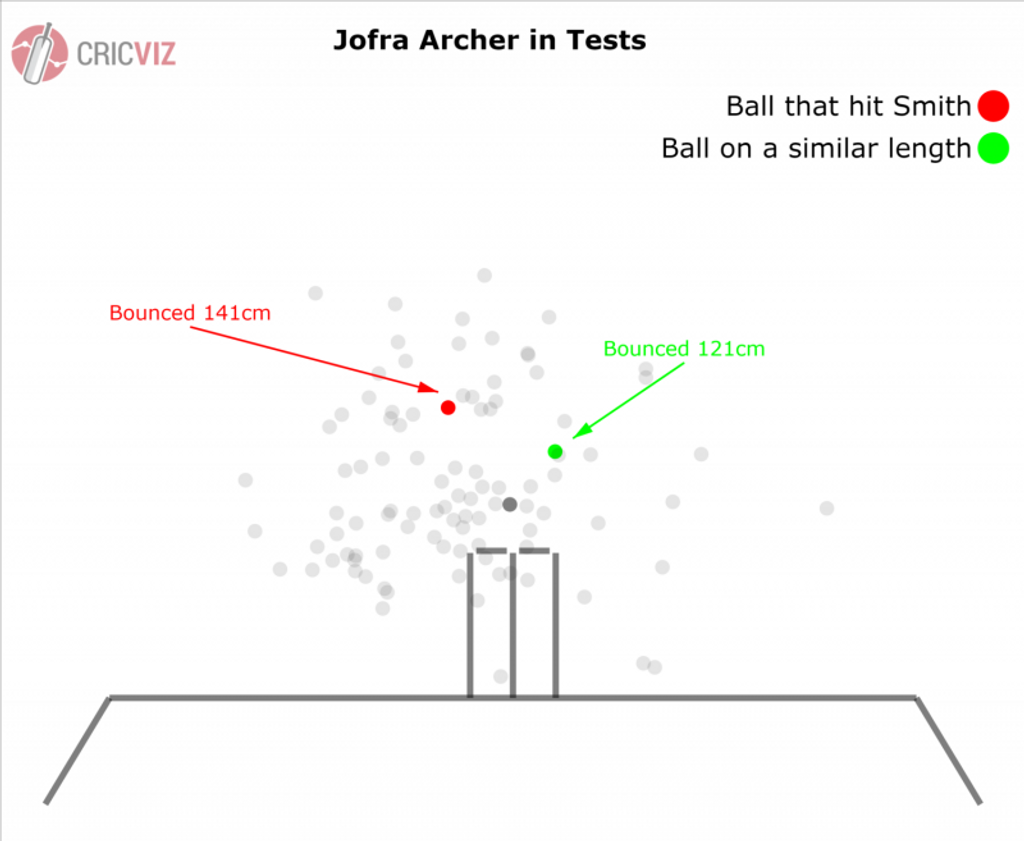

Archer’s delivery didn’t do that much that you wouldn’t expect. It was 147kph, but we knew that Archer bowled quick; he’s bowled quicker deliveries in the Test. What it did do was really, really get up on Smith. Similar deliveries, pitching on that length, bounced about 20cm less. That’s the difference between wearing one on the arm, and wearing one on the helmet. It took the intervention of the earth, a clump of grass or dried mud where it shouldn’t be, to get through him.

It’s important to not gloss over the sensation in the ground in the moments after. When he fell to the floor, on his front, it was as if Lord’s had been plunged into deep, cold water, a grim silence enveloping all around. The ground felt sick, submerged in a thick blanket of dread and fearful anticipation.

Archer stood apart from the rush of medics and concern, nervously laughing as Jos Buttler tried to calm his colleague, a 24-year-old man who feared that perhaps he’s just been responsible for the worst thing that could happen on a sports field, that could happen anywhere. A 24-year-old man doing his job, doing it well, doing nothing wrong.

This is the trade-off, isn’t it? This is the fire we’re playing with, the flames we dance around in those heightened moments. The thrill of cricket played at that high pace is that, implicitly, just below the surface is a layer of danger we try not to acknowledge. How could you? How could you genuinely enjoy the spectacle of furious risk and reward that is fast bowling, with that at the forefront of your mind?

The Australian dressing room say that Smith was cleared to bat, and sat waiting for 10 minutes before finally walking out. We can only wonder what on earth can have been going through his mind in those moments. Perhaps he was thinking of himself, of what could have happened, of what could have been. Perhaps he was thinking of similar situations, of absent friends, alone with us all in newly stinging recollection.

Seemingly, and unsurprisingly given it was Steve Smith, he was thinking about batting – for his sake, you hope he was. Justin Langer says that Smith said: “I can’t get on the honours board unless I get out there.” Smith is a remarkable man, but in truth, Smith’s return to the field felt like an unwanted, uncomfortable sequel to the perfection that preceded it. We didn’t need it, and we needn’t linger on it.

What we should linger on, for as long as we can, is the pure joy of watching the best against the best, the fastest a nation can offer against another nation’s most capable. Lord’s has seen some sights – plenty this summer alone – but it’s rarely seen a day like today. Jofra Archer, against Steven Smith, was one of the great contests.