In the 2020 edition of Wisden Cricketers’ Almanack, Colin Shindler revisits the infamous ‘Stop the Seventy Tour’ saga and the impact it had on the cricketing summer and beyond.

Colin Shindler’s book on the events of 1970, Barbed Wire and Cucumber Sandwiches, is published this summer

When Brian Johnston died in January 1994, Test Match Special’s lunchtime interview “A View from the Boundary” passed to Jonathan Agnew. South Africa would be touring England for the first time since readmission – and playing their first Test at Lord’s since 1965. With commendable eagerness, Agnew thought it would be a good idea if his guest on the Saturday were Neath MP Peter Hain who, as chairman of the Stop the Seventy Tour committee 24 years earlier, had been a bête noire of the English cricket authorities.

TMS’ long-standing producer, Peter Baxter, was not initially as keen as Agnew had hoped. Baxter had joined the BBC in 1966, and remembered only too well the events of 1970, when the invitation to the South Africa Cricket Association was withdrawn 12 days before their players were due to land. He thought the BBC hierarchy would remember, too, and treated Agnew’s bold idea with circumspection. Had Johnston been alive, Baxter believed, he would have rejected Hain (who had been brought up in South Africa), or insisted another broadcaster interview him. For Johnston, Hain remained the sideburned 19-year-old student who had wantonly destroyed a summer’s cricket.

Eventually, recognising Agnew’s enthusiasm, Baxter relented, and the invitation to Hain was despatched and accepted. As play began that Saturday, Trevor Bailey – one of the TMS summarisers – took Baxter aside and quietly requested a schedule that would not require him either side of lunch: Bailey wanted to avoid any contact with Hain, whom he had not forgiven for what he still regarded as a sorry episode.

Looking back 50 years, one is struck by the similarity to events in the UK following the 2016 referendum on membership of the European Union. Passions were inflamed, and people who had previously shown little interest in cricket or politics grew exercised; families were divided, friendships destroyed.

There had been controversy in 1968, of course, in the wake of John Vorster’s refusal to allow Basil D’Oliveira to enter South Africa as part of the MCC touring squad, but in the public mind that was a predictable decision taken by a foreign government determined to protect apartheid. MCC had been criticised in liberal quarters for what appeared to be a spineless move not to include D’Oliveira in the original party, though the club’s membership had voted in support of the committee. As far as they were concerned, that was the end of the matter. It wasn’t: middle-class opinion in Britain had been offended, and the impact would be felt in 1970.

The wider events of 1968 had changed the world’s social and political landscape. The Tet Offensive in Vietnam had convinced Walter Cronkite and other American commentators that the conflict could not be won; anti-war protests intensified accordingly. In March, British television audiences were horrified by the spectacle of policemen beating up anti-war demonstrators outside the US Embassy in the genteel surroundings of Grosvenor Square.

Meanwhile, the assassination of Martin Luther King in April confirmed to civil-rights campaigners the belief that non-violent protest had to be replaced by the more radical actions advocated by Stokely Carmichael, Huey Newton and the Black Panthers. Letters to the Guardian from Hampstead protesting about the iniquities of apartheid were never going to cause a moment’s discomfort to Vorster: direct action, it seemed, was the best way of bringing home to South Africa’s players and their admirers exactly what a large number of British people felt.

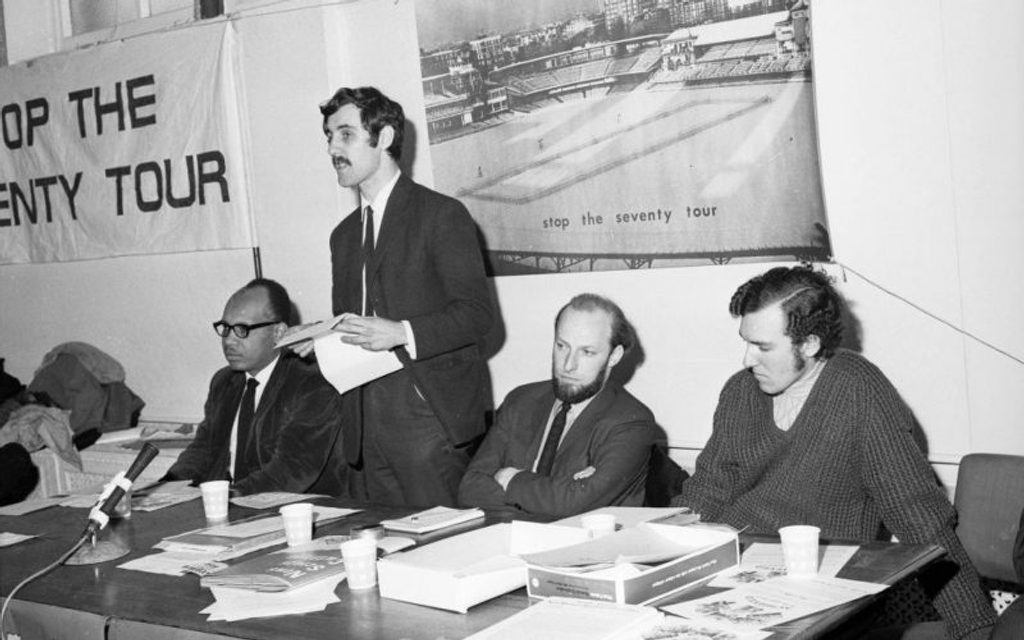

Taking a stand: (right to left) Peter Hain. Jeff Crawford (secretary of the West Indian Standing Conference), Mike Brearley and Mike Craft, an STST committee member, circa March 1970

Taking a stand: (right to left) Peter Hain. Jeff Crawford (secretary of the West Indian Standing Conference), Mike Brearley and Mike Craft, an STST committee member, circa March 1970

The main objective of Stop the Seventy Tour, formed in 1969, was to force MCC into withdrawing their invitation to SACA, but as fate would have it the Rugby Football Union had arranged a tour of the British Isles by the Springboks for the winter of 1969/70. Cricket and tennis in South Africa were played largely by the descendants of British settlers; rugby was the sport of the Afrikaners, the originators of apartheid.

The Springboks were to play 26 matches in three months, including one against each of the four home nations, but from the moment they arrived in London in October 1969, they faced the full wrath of Britain’s Anti-Apartheid Movement. MCC looked on with trepidation: whatever happened now would likely be replicated at the cricket the following summer. Their worst fears were realised.

The AAM were a loose alliance of students, trade unionists, politicians and churchmen, and their more militant members got to work: they invaded the rugby matches, hijacked the team bus, and handcuffed themselves to Twickenham’s goalposts. Scarcely a match was uninterrupted, and the impact on the South Africans was significant: they were beaten by Oxford University and lost two of their internationals, a failure that disconcerted the public back home – not just on a sporting level.

Everyone knew that if an 80-minute game of rugby could not be defended by the police, a five-day Test match could hardly be protected either, except by a large security force costing more than cricket’s authorities could afford. And if the match took place behind barbed wire while being patrolled by guard dogs, what sort of atmosphere was that?

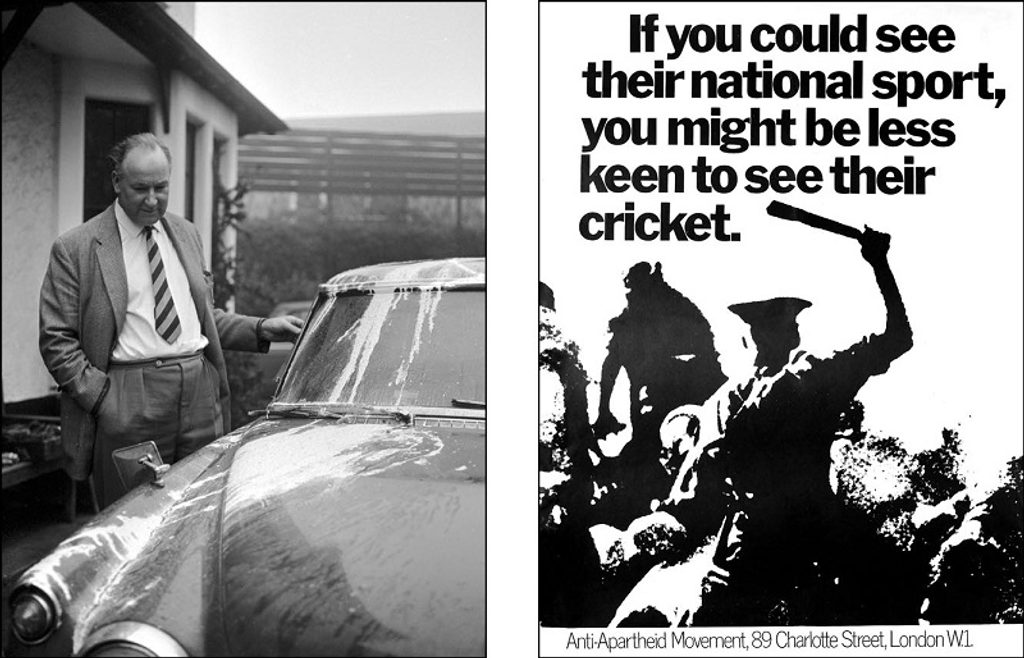

Between the Springboks’ internationals against Ireland and Wales, attention suddenly focused on the forthcoming cricket tour. On the night of January 19, in a co-ordinated attack organised by a covert anti-apartheid group, ten county grounds were broken into. At Bristol, weedkiller was poured on the pitch, and slogans painted on the glass-fronted Jessop scoreboard. At Hove, the covers and heavy roller were daubed in paint. At Northlands Road, Southampton, the scoreboard was defaced, and walls graffitied. At Cardiff, Wilf Wooller’s notoriously short temper was not improved when he discovered that, in addition to digging up the pitch and pouring tin tacks into the hole, the “hooligans” had given his car a fresh coat of paint. A small fire was started at Lord’s, and there was damage at The Oval, Headingley, Old Trafford, Grace Road and Taunton.

Hain carefully distanced himself from those events: despite his belief in direct action, he was uncomfortable with violence. Yet some MCC members regarded him with suspicion. “I met E. W. Swanton when I encountered him during the course of the STST campaign, and of course I read what he wrote,” says Hain. “He was extremely courteous and engaging, which I didn’t expect, whereas Wilf Wooller was not. Billy Griffith, who was conservative with a big C and a small c, was polite whenever I handed him a letter. He had a clipped politeness, which was very much not the case with Wooller, who was extremely aggressive towards me. The first thing he said was: ‘I want to see you behind bars, and I am going to make sure that happens.’”

Painting a grim picture: Wilf Wooller, secretary of Glamorgan, surveys his car; a poster published by the Anti-Apartheid Movement

Painting a grim picture: Wilf Wooller, secretary of Glamorgan, surveys his car; a poster published by the Anti-Apartheid Movement

The events of January 19, widely condemned as gratuitous violence, simply confirmed the opinions of MCC and the Cricket Council (MCC in all but name) that South Africa’s visit had to go ahead, if only to show that decent people could not be bullied. The Council ascertained that playing cricket in England was a legal pursuit; preventing it, therefore, was not. The tour, according to opinion polls, was still supported by the great majority of Britons. In the Council’s view, cancellation would be bowing to the pressure of hooligans and fascists. If the tour was going to be called off, the government would have to do it. The rule of a minority, many of whom, it was believed by Daily Telegraph readers, did not wash as often as they should, was not part of the British way of life.

The Council did indeed suggest the counties invest in barbed wire, searchlights and guard dogs. Nottinghamshire informed Lord’s it would cost £250 to install lights at Trent Bridge, adding £6 a week to the electricity bill. At Edgbaston, Warwickshire put the cost at £300, plus £120 a week to pay security patrols. At Lord’s, MCC had already spent £200 on Dannert wire, a form of toughened barbed wire. When a much-anticipated Cricket Council meeting took place in the Long Room on a cold, dark February evening, it was possible to look through the windows and see, not the run stealers flicker to and fro, but the barbed wire silhouetted against the snow-covered turf.

Watchtowers and guard dogs added to the impression that the long shadows on county grounds were now of concentration camps. In a sense, the grounds had resumed some of their wartime appearance, when Lord’s was commandeered as an air-crew receiving centre, The Oval made ready for prisoners of war, and Headingley taken over by the Royal Army Medical Corps and used as a mortuary. In defence of liberty and freedom, the cricket authorities seemed prepared to turn grounds back into the fortified camps everyone assumed had been consigned to history.

At the meeting, the counties and MCC backed the tour, while cutting the number of fixtures from 28 to 12. Instead of coming at the end of April, the South Africans would now arrive at the start of June; and instead of playing every county, they would play mainly at the major city grounds – the six Test venues, plus Bramall Lane and Swansea – where it was easier to maintain security. Artificial pitches would be prepared in case of vandalism.

The recently formed Professional Cricketers’ Association (regarded by some as the only trade union whose members were more right-wing than their employers) voted overwhelmingly in favour of the tour, despite a passionate speech from their president, John Arlott, advocating cancellation. The cricketers were not interested in politics, and wished only to be allowed to play – an attitude that chimed with the arguments employed at Lord’s.

Taking it to the wire: pitch preparation at The Oval in March 1970

Taking it to the wire: pitch preparation at The Oval in March 1970

Mike Brearley was one of a handful of players who voted against the tour, but he understood why the majority of his colleagues felt as they did. “I wasn’t surprised at the PCA vote,” he says. “Many players made a living out of South Africa. They went there during the winter, coached out there, and maybe played league cricket or even for a state side. They saw businessmen and actors going there and doing well out of it, and they didn’t see why they should take the brunt of it, even if they were sympathetic to the Anti-Apartheid Movement.”

As views became entrenched, news arrived of some glorious cricket taking place in South Africa: Barry Richards, Mike Procter, Eddie Barlow, Graeme Pollock and the rest had whitewashed Australia 4–0. The prospect of seeing them in England whetted the appetite, and a fund was set up to raise £200,000 for security. The right-wing papers supported the tour; the more liberal papers did not. Tempers continued to fray.

David Sheppard, Bishop of Woolwich and an advocate of cancellation, attempted to arrange a conciliatory meeting; Peter May, his Cambridge friend and former England colleague, replied bluntly that they had nothing to talk about. When Arlott wrote in the Guardian that he would not broadcast on TMS if the tour went ahead, he received a large postbag, mostly in agreement, but some severely critical. According to his son, Tim, the most unpleasant was written by May, who was held in great regard by many, not just for his batting but for his decency. Yet on South Africa, he was uncharacteristically intemperate. His relationship with Sheppard never recovered.

The Labour government were reluctant to issue a direct order to cancel the tour, but a general election was approaching. Stop the Seventy Tour was adept at attracting television crews to their stunts, and the government feared news broadcasts featuring large-scale disruptions on streets and cricket grounds, just as the Conservatives were making law and order a central part of their manifesto.

On May 14, an emergency debate was called in the House of Commons. The prime minister, Harold Wilson, detested South Africa, and – to the fury of his political opponents and MCC – let it be known in various interviews that he would look favourably on peaceful protests. By now, even Swanton believed the tour would not be in the interests of cricket. South Africa were expelled from the Olympic movement, and 13 African countries announced that, if the tour were to proceed, they would boycott the Commonwealth Games in Edinburgh in July. Even the well-heeled residents of St John’s Wood, fearing trouble in the streets, pleaded with Lord’s to call it off.

Faced with overwhelming pressure, and with the South Africans due to get under way against Southern Counties at Lord’s on June 6, the Cricket Council met on May 18. The following day, Griffith read a long-winded, self-serving statement confirming the tour. Having called an election for June 18, the government ran out of patience. The home secretary, James Callaghan, summoned the Council and told them the tour had to be cancelled. It was over. On May 22, the Council announced that, with deep regret, they had no option but to comply.

MCC and their supporters had claimed it was more beneficial for non-white South Africans for bridges to be built and windows to be opened so that positive contact could be maintained. Their opponents believed sporting isolation was much more likely to force political change. It took another 20 years, but history has shown which side was right.

The opponents for the five scheduled Tests became a Rest of the World team captained by Garry Sobers. Yet taking the field in the first match were Richards, Procter, Barlow, and Graeme Pollock; in the third, they were joined by Peter Pollock. Wisden 1971 included one article on the matches, written by the editor, Norman Preston, and another on the tour’s cancellation, for which he commissioned the statistician Irving Rosenwater, rather than Arlott, the obvious candidate and a regular contributor.

Rosenwater wrote a measured piece, but his political sympathies were apparent as he described the mayhem of the protests in terms of arrests made and policemen injured. It added little lustre to the Almanack. Robert Winder, the book’s historian, wrote in 2013 that an article by Arlott “would have cemented Wisden’s moral authority around the world. As it was, it put a question mark over the idea that cricket even knew the meaning of the ‘fair play’ culture it so keenly espoused.”

Perhaps we should not be too censorious. Fifty years from now, it is possible historians will wonder how we made such a meal of Brexit.