Shortly after WG Grace’s death, a story surfaced about how he once spotted a young gentleman amateur in the Gloucestershire changing-room reading a volume of Homer. “How can you make runs, Bill, when you are always reading?” Grace enquired. “I am never caught that way.” The amateur, William Hemingway, drifted out of first-class cricket into a more rewarding occupation as secretary of a Yorkshire bridge club. As for the anecdote, it acquired a life of its own. Hemingway’s team-mate RW Rice, who witnessed the scene, felt the story illustrated how Grace was “all for the rigour of the game”. In Rice’s version, Grace thought cricket was too serious for a player to distract himself with a book. But in subsequent accounts the story was used to support the theory that Grace never read a book in his life.

WG Grace, born on July 18, 1848, did more to establish and popularise cricket than anyone in history. In the 2015 Wisden Cricketers’ Almanack, his biographer Richard Tomlinson examined some of the myths surrounding him.

Shortly after WG Grace’s death, a story surfaced about how he once spotted a young gentleman amateur in the Gloucestershire changing-room reading a volume of Homer. “How can you make runs, Bill, when you are always reading?” Grace enquired. “I am never caught that way.” The amateur, William Hemingway, drifted out of first-class cricket into a more rewarding occupation as secretary of a Yorkshire bridge club. As for the anecdote, it acquired a life of its own. Hemingway’s team-mate RW Rice, who witnessed the scene, felt the story illustrated how Grace was “all for the rigour of the game”. In Rice’s version, Grace thought cricket was too serious for a player to distract himself with a book. But in subsequent accounts the story was used to support the theory that Grace never read a book in his life.

Myths, half-truths and factual errors have always enveloped Grace. A check of his estate-duty valuation shows he kept 70 books in the drawing room of his last home in south-east London, plus another 50 in the billiard room, and “various” other cricket books, which must have included his complete set of Wisden. Just before his death, Grace told his grandchildren he hoped they would “always love books”.

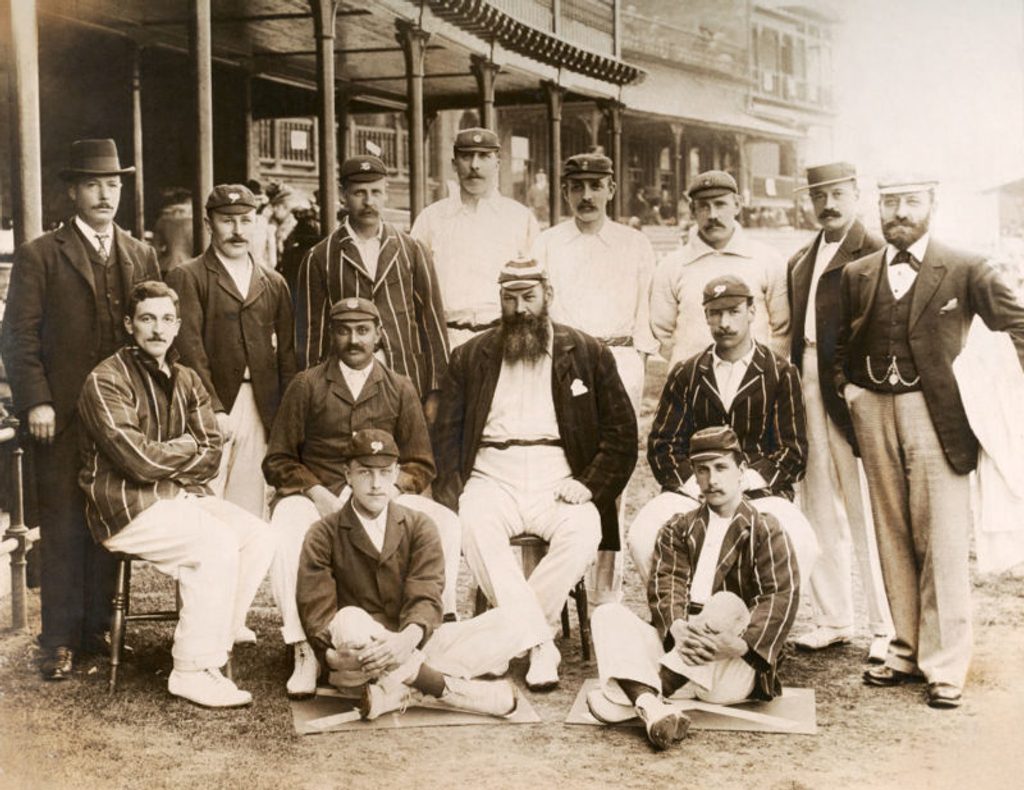

Grace (middle row, second from right) with the rest of the England side who played the first Test against Australia at Trent Bridge, June 1899

Grace (middle row, second from right) with the rest of the England side who played the first Test against Australia at Trent Bridge, June 1899

Rather like Grace’s centuries, the errors gather momentum after his cricketing breakthrough aged 15 with an astounding 170 against the Gentlemen of Sussex at Hove. In the late 1860s, Grace did not “waver” over whether to play as a professional or an amateur, as MCC’s most recent official history suggests. The real scandal was why it took MCC almost five years to elect him a member. The first – almost successful – approach to get Grace to Australia came in 1869, not 1872, as was subsequently reported. And when he finally took a team there, in 1873, it was widely believed he charged a personal fee of £1,500. Yet there is no firm proof to support the assumption. What is clear is that the tour’s chief promoter was close to bankruptcy, and in no position to guarantee anything close to this sum. Back in England Grace’s 1879 testimonial – jointly organised by Gloucestershire and MCC – was no triumph at all, and very nearly an embarrassing flop.

Grace had suffered some bad luck. MCC secretary Bob Fitzgerald was ideally qualified to organise a fund for the club’s superstar. However, he went insane from tertiary syphilis in 1876, a few months before the testimonial’s launch, and was incarcerated in a private asylum in Chiswick. The MCC committee decided to “resign” Fitzgerald, who was locked in his room, “naked, dirty and noisy,” ripping bandages off the carbuncles sprouting on his body. His successor, Henry Perkins, mismanaged the testimonial so badly that the eventual fund was not enough to buy Grace a profitable medical practice, as had been originally intended. This is why he ended up as a medical officer employed by a Poor Law union in Bristol.

Correcting the details of Grace’s life matters because, strange though it seems, he is still underrated and misunderstood, both as a cricketer – even supposedly enshrined versions of his gamesmanship do not always stand up to scrutiny – and as arguably the most famous sporting celebrity in the British Empire during the half-century before the First World War. Measuring WG’s fame is an imprecise science, but here is a rough yardstick: enter the search terms WG Grace and cricket, and the British Library’s online newspaper catalogue throws up 37,725 articles for 1850-99; substitute with W. E. Gladstone and politics, and it yields 18,823. Grace’s fame stretched far beyond his main game. In 1893, for instance, the Society of Authors invited him to act as an honorary steward at their annual dinner, alongside Oscar Wilde. Sadly, it seems Grace was detained by a match at The Oval, and did not show up.

He would not have been out of his depth in such company. Contrary to another myth, he was a fine, clear writer when he turned his mind to the only subject that interested him – how to play cricket. WG’s Little Book, produced at the end of his life, is a minor masterpiece, containing such gems as a whole chapter on playing the googly. Grace was much less interested in checking the memoirs that others produced under his name. In the preface to his 1895 History of a Hundred Centuries, he supposedly sent his “sincerest thanks to Mr Wisden, of Cranbourn Street, Leicester Square, for his kindness” in making available “his complete set of ‘Wisden’s Almanac’ [sic]” during research for the book. The real WG knew perfectly well that John Wisden had died long before.

Grace’s near-total absence from general histories of 19th-century England is hard to fathom. It took a great cricket writer to address the critical question about him, almost 50 years after his death. In Beyond a Boundary, published in 1963, C. L. R. James asked what made WG “the pre-eminent Victorian”. James found the key to his crowd-pulling magnetism: no one had ever played sport with such sustained, thrilling aggression. “He was news,” he wrote, “and as he continually broke all precedents (even his own) before he had passed the middle twenties, each amazing new performance told the public, cricketing and otherwise, that here was one of those rare phenomena, something that had never been seen before and was not likely to be seen again.”

Illustration of Grace batting at Lord’s, 1895

Illustration of Grace batting at Lord’s, 1895

James might well have erred when he argued that Grace was at heart a pre-industrial countryman who was “in every respect that mattered a typical representative of the pre-Victorian age”. Ironically James, a Marxist, swallowed the establishment myth that, because Grace grew up in a village, spoke with a Gloucestershire accent, and liked hunting and shooting, he was by definition a rustic. No description could have been less true of a man who relished all things modern, from trains and planes to telegrams. Described by John Arlott in 1948 as being of “pure country strain”, Grace in fact counted no one who lived off the land among his extensive family and immediate ancestors. His people were doctors and teachers, the backbone of the era’s rising professional classes.

Grace’s problem was that his family did not have the means to provide him with a financial platform to play full-time as an amateur. The charge of hypocrisy has stuck ever since, yet what his detractors interpreted as greed was fuelled by legitimate financial anxiety. WG’s father left so little to his widow that the family immediately sold off his prized hunting horse. His uncle Alfred, WG’s boyhood cricket coach at The Chesnuts, their Downend home, near Bristol was a bankrupt, as was Grace’s father-in-law, a failed printer. Between 1874, when he returned from Australia, and 1879, when he qualified as a doctor, Grace spent almost half the year as an unpaid medical student, with a wife and, eventually, three children to support.

Grace with his wife Agnes, circa 1900

Grace with his wife Agnes, circa 1900

So how much did he earn from cricket? In the 1870s, Grace played a lot of professional against-the-odds games versus sides as bad as “22 of Oxford Music Hall” for his United South of England XI. This was in effect a star vehicle which would have collapsed without him. It appears from the accounts for a match in Dublin in 1876 that WG’s personal going rate was £20 (about £1,600 today), a sum that might not have included his travelling expenses across the Irish Sea. WG was paid far more than professionals such as James Lillywhite, jun. of Sussex, another USE regular. But then the crowds had come to see Grace.

The allegation that he earned yet more income as a shamateur from his MCC expenses is a red herring, for two reasons. First, these expenses were expected to cover travel and accommodation, their stated purpose; second, the sums involved were not that big. In 1874, for example, the MCC committee ruled that Grace’s total expenses for playing for the club during Canterbury Week should “not exceed £5”.

When he looked at the man who wrote this minute, WG could have reasonably argued that MCC – as the upholder of the game’s amateur ethos – were the bigger hypocrites when it came to money. Fitzgerald, MCC secretary between 1863 and 1876, set up his own private Lord’s Grand Stand Company in 1867 with a board that included three past or future club presidents. Fitzgerald’s venture folded two years later, after MCC claimed their right to take over his increasingly profitable business. In the 1870s, the Grand Stand was guaranteed to fill up whenever Grace appeared and, according to Fitzgerald, to empty as soon as “The Champion” was out.

Few of the MCC grandees who benefited from Grace’s appearances for them fathomed the nature of his genius. Canon Edward Lyttelton, a Cambridge and Middlesex amateur in the late 1870s who ended up as headmaster of Eton, recorded in MCC’s 1919 Memorial Biography of Dr WG Grace, “no one ever had a more unanalytic brain”. Like others, Lyttelton missed the analytical quality of Grace’s batting, which was evident even before he received his first ball.

Arriving at the wicket, Grace would scrutinise the pitch, survey the field and, after asking the umpire for his guard (usually middle and leg), scratch a mark behind the crease with a bail. He would double-check his mark with the umpire, replace the bail – taking care to wipe any dirt off the stub – and finally take guard. The sight that confronted the bowler was both disconcerting and deliberately intimidating: in defiance of the coaching manuals, WG’s bat hovered above the blockhole, while his front foot pointed down the wicket, toes cocked.

It was a platform for attack, with the clear intent (in another deviation from orthodoxy) to hit off the front foot wherever possible. Like a modern one-day player, Grace looked for runs even in defence. “When you block,” he told schoolboys, “do not be content to stop the ball by simply putting the bat in its way – anyone can do that – but try and score off it too.” Grace had other self-made shots; it helps to think of him, just a little, as one of the great Victorian inventors. One was a forcing on-side stroke off the back foot. “His feet came together as he drew himself up and there was little space for the bat to swing,” recalled H. E. Roslyn, cricket correspondent of the Bristol Times and Mirror from 1887. “Yet so much wrist power was employed that mid-on had little chance of stopping the ball, and long-on experienced considerable difficulty in saving a four.” Replace WG with KP, and Roslyn’s image still works.

For Grace, the fabled corridor of uncertainty was just another run-making channel. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle looked on in amazement as WG, now past 50, took on “that most uncontrollable of all balls, the good-length ball outside off stump… Stepping across the wicket while bending his great shoulders, he watched closely as it rose, and patted it with an easy tap through the slips… Never with the edge, but always with the true centre would he turn the ball groundwards, so that it flashed down and then fizzed off between the grasping hands, flying with its own momentum to the boundary.” Without the craft that lay behind it, Grace’s slow round-arm bowling would have been as bad as many batsmen fatally thought it to be. “His run – more correctly, his scuffle – up to the wicket was short with elbows bent,” wrote Roslyn. “Then his right arm would be thrust out with hand not much above the head and the ball would roll out of his hand. The action suggested a leg-break, yet there could have been little finger-spin. Success was earned by accuracy of pitch, and the enticement to batsmen to make false strokes.”

It took one great bowler to spot another. “There is not a cricketer on earth has a better head than Grace; indeed I never came across a man that had so good a one,” remarked Australia’s Fred Spofforth in 1886. “He seems to be able to divine what next to send, and very frequently he indeed so juggles with you that you are beaten in spite of yourself. This talent is the very finest attitude of a bowler.”

But it was Grace’s batting that drew the crowds. Wisden sounded as though it had attended a sado-masochistic orgy rather than a cricket match when it described one particularly brutal assault in August 1876. His 133 not out in well under two hours for MCC against Kent at Canterbury featured “hitting almost unexampled in its brilliant severity”. Nor was Grace finished. Next day he moved to 344, refreshing himself with champagne not once, as he claimed in his published memoirs, but “pretty often”, as he had recorded more honestly in the first draft. WG may be the only batsman to break the record for the highest first-class innings while drunk.

That careful edit provides a clue to Grace’s startling physical decline from about 1880. He liked food and drink almost as much as batting, and his intake is suggested by a procession of banquet menu cards. One, for a feast at the Plough Hotel in Cheltenham in 1878, included “Lobster Patties, Stewed Pigeons, Veal Cutlets, Curried Chicken” – and much else besides. Grace’s drinking was less widely publicised, and he was claimed – absurdly – by the Victorian temperance movement as an abstainer. But circumstantial evidence suggests he may have turned to alcohol to relieve stress, especially following his daughter Bessie’s death from typhoid in 1899. During the second half of his career, he increasingly preferred a whisky and soda during the lunch interval to water or tea – although in a match at Cambridge in 1904 he obligingly downed three quick sherries as his university opponents tried to get him drunk. The golf writer Bernard Darwin witnessed Grace perform his party trick of drinking an entire bottle of champagne, getting down on all fours, then standing up with the empty bottle balanced on his head.

Grace pictured on his 66th birthday, July 1914

Grace pictured on his 66th birthday, July 1914

His growing girth affected his cricket. He bulked up from over 12 stone (he was 5ft 9in) in his prime in the early 1870s to about 18 stone by the early 1900s; his batting got worse. Having been better by a mile than any other batsman before 1880, Grace slipped down the ranks over the next two decades, as first Arthur Shrewsbury, then a succession of others, overtook him. By 1891, his form and fitness were so poor that he was not worth his place in the England team he took to Australia. “I can very plainly see a crop of troubles may spring up from WG’s knee,” the team’s financier, Lord Sheffield, fretted shortly before departure, after learning of Grace’s latest injury.

Grace’s improbable Indian summer in 1895, when he scored his 100th hundred, one of nine for the season, prompted a second, much larger testimonial, and deluded him into carrying on playing Test cricket until 1899. This was a humiliating mistake. In the end, the 50-year-old Grace dropped himself, after a section of the Trent Bridge crowd hooted with derision every time he tried to field the ball.

MCC ignored such embarrassments when they published their Memorial Biography in 1919. In reality, it was a compilation of anecdotes by a small band of amateurs who had played with Grace, plus a few non-cricketing friends in later life, all stitched together by the cricket writer and publisher Sir Home Gordon. In his preface, he understandably made no mention of the book’s fraught genesis: Grace’s widow Agnes had tried to get the club to fire Gordon, who had written a piece years before that had offended her husband. Gordon (whose idea the book was) refused to budge, and a compromise was struck: MCC drafted in their president Lord Hawke, a friend of Gordon, and Lord Harris, as nominal co-editors, but in practice his minders, ensuring he kept to a tight brief laid down by Agnes that forbade anecdotes about Grace’s private life. Behind the scenes, Gordon let off steam by sniping about one of the contributors, Canon Tatham (“old men are bores”), and Grace’s uncle Alfred (“a ridiculous personage”).

A better way to remember Grace lies in the suburbs of south-east London. In the early 1900s, he captained and managed the London County Cricket Club, owned by the Crystal Palace Company. London County ceased playing first-class games in 1904, but Grace continued to organise and captain them in minor cricket. In 1909, a year on from his last first-class match, he moved from Sydenham to Mottingham after the Crystal Palace Company filed for bankruptcy. At Fairmount, his house there, Grace followed the habit of a lifetime by laying out a practice net in the back garden. He joined Eltham Cricket Club, whose professional Bob Haywood and young son Archie would visit him at home once a week to bowl at him.

The start of the 1914 season found WG engaged with Eltham CC committee business, firing off notes to club colleagues on such urgent matters as marking out the boundary, paying the professional, and getting another fixture when a game fell through. Club cricketers know the type well: the older member who has stepped down a level and is now an indispensable, if slightly annoying, committee man. The only difference was that the grey-bearded giant clutching his whisky and soda in the pavilion just happened to be the greatest cricketer of all time.

Why did Grace bother? There is only one explanation that makes sense. At the end of his life, he still loved cricket so much that he wanted to play forever.

Richard Tomlinson is the author of Amazing Grace: the man who was W.G. (Little, Brown, 2015)