Tony Lock was a key figure in Surrey’s all-conquering 1950s teams. After playing a key part in England’s 1953 Ashes win, he was named a Wisden Cricketer of the Year.

Tony Lock had a remarkably long Test career, returning after a lengthy absence to play his final Tests in the Caribbean in 1968. In 49 matches, he took 174 wickets at 25.58. He is Surrey’s second-highest wicket-taker with 1,713.

The success of Surrey in reaching the top of the Championship three times in the last four seasons and the return of the Ashes to England have been due in no small way to the tenacious left-arm slow bowling of Graham Anthony Richard Lock. Born at Limpsfield, close to the north-west boundary of Kent, on July 5, 1929, this sandy-red-haired cricketer appears to have a career full of possibilities before him.

In the days when Robert Abel, Tom Hayward and Sir John Hobbs thrived at Kennington Oval and Len Hutton hit his record 364 there was little room there for a bowler of Tony Lock’s type. He is the first genuine left-arm slow bowler within living memory to hold a regular place in the Surrey team. For this state of affairs he has to thank his namesake, H.C. Lock, who re-joined Surrey at the end of the war and re-shaped The Oval from a prisoner-of-war camp into a cricket arena. In the process, The Oval never returned to its pre-war condition and now the bowler wages a genuine conflict with the batsman.

Like the gifted artist in music, the really great sportsman usually emerges only after devoting himself to hours of constant practice. This has been the case with Lock. First, he possessed the priceless asset of natural ability. He cannot remember when he played cricket originally. He has a picture of himself at the age of six dressed for the game, wearing pads and holding a bat. As a boy, Lock always delighted in throwing and catching any type of small ball.

[breakout id=”0″][/breakout]

He used to watch and play cricket on the pretty village green, and at 14 he captained the Limpsfield Church of England school. The headmaster, Mr. L.A. Moulding, was an enthusiastic cricketer and a splendid coach. Like most boys, young Lock craved for speed and he used to bowl as fast as he could and hit the ball with all his might. Being captain, he exercised his right to open the batting and the bowling, and once he began an innings by hitting the first three balls for six. He would have continued, but Moulding, his partner, advised a little discretion.

Leaving school, Lock became apprenticed to a cabinet maker. He never entertained the idea of climbing the dizzy heights of a professional cricketer, but Moulding saw his potential talent and brought it to the notice of a local resident – none other than Sir Henry Leveson Gower, a man who devoted almost his whole life to the interests of Surrey cricket.

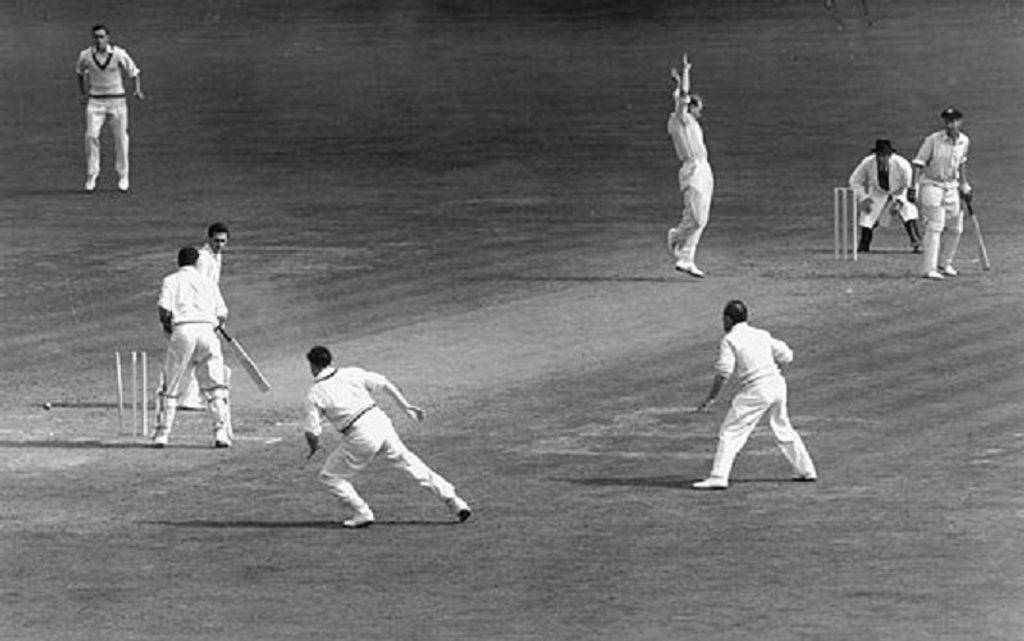

[caption id=”attachment_163943″ align=”alignnone” width=”800″] Tony Lock celebrates Neil Harvey’s wicket during the Oval Test of 1953. Lock’s 5-45 helped England to their first win at home against Australia post WWII[/caption]

Tony Lock celebrates Neil Harvey’s wicket during the Oval Test of 1953. Lock’s 5-45 helped England to their first win at home against Australia post WWII[/caption]

Consequently, Lock played for Surrey Colts in 1944 and 1945. He showed such promise that in 1946 he was signed as a professional before his 17th birthday. The same year he made his first appearance in the County Championship, playing one game against Kent at The Oval. In 1947 his opportunities in the first team were again limited to one game, but he helped the Second Eleven to be runners-up in the Minor Counties competition by taking 42 wickets. National Service claimed him in 1948, but he appeared in one match at Lord’s where he assisted The Army to beat Royal Navy by eight wickets. One of his three victims was his future England and Surrey colleague, P.B.H. May.

Returning to The Oval in 1949, Lock soon established himself in the senior side. In those days his main virtues were accurate length and direction. More bite was needed in his spin. Here Lock pays tribute to the help he received at The Oval nets from J.C. Laker, who showed him the way he imparted his off-spin with the first finger of his right hand. Lock realised that much practice would be required to produce Laker’s methods. The opportunity came when Mr. D.A. Lawrence, a Croydon business director, appointed Lock as winter coach to an indoor cricket school with two nets.

[breakout id=”3″][/breakout]

For two whole winters he spent six days a week giving lessons and improving his own technique, but this constant practice produced another problem. A beam in the roof at the bowler’s end caused Lock unwittingly to drop his high action with the result that in 1952 his delivery became suspicious. A week after making a highly successful debut for England against India at Old Trafford he was no-balled three times by the square-leg umpire, W.F. Price, for throwing in the Surrey and India match at the Oval.

Again, Mr. Lawrence came to the rescue. The beam at the school was raised 14 inches and during another whole winter’s practice the faults were ironed out, so that in 1953 Lock not only returned to his previous tidy action but his spin was as vicious as ever. Lock was again no-balled for throwing or jerking at the beginning of the recent tour of the West Indies and for a time he refrained from bowling his faster ball.

[caption id=”attachment_163944″ align=”alignnone” width=”800″] Tony Lock acknowledges the crowd from The Oval balcony after England’s win over the West Indies, circa 1957[/caption]

Tony Lock acknowledges the crowd from The Oval balcony after England’s win over the West Indies, circa 1957[/caption]

He considers that, although he took eight wickets for 26 and five for 43 in Surrey’s final match against Hampshire on a drying pitch at Bournemouth, his finest performance with the ball was at the beginning of June, the day after he had been chosen to make his first appearance for England against Australia at Trent Bridge. On an almost perfect Oval pitch, in the presence of F.R. Brown, chairman of England’s Test selectors, Northamptonshire were dismissed for 160 and Lock’s analysis was 31.2 overs, 17 maidens, 55 runs, 6 wickets.

Unfortunately, that prolonged effort at spinning the ball wore away the skin of his left finger, and he was able to play for England in only the last two Tests, at Headingley and The Oval. Whatever may be Lock’s opinion, many people will consider his finest work with the ball was accomplished on that Tuesday afternoon of the final Test at The Oval in August when he and Laker brought about Australia’s dismissal for 162, leaving England to make 132 and recapture the Ashes. Lock five for 45; Laker four for 75. Indeed a triumph for the two men who previously had taken the trouble to master the intricacies of spin on this very ground.

[breakout id=”2″][/breakout]

At the end of the season Lock’s finger was still raw, but before he went to West Indies it was hard and firm; but like all bowlers of his kind he will have to watch its condition carefully for if the skin becomes too hard it will split just as it does when it is soft. Laker has the same problem.

While the leg-break is Lock’s main weapon, he can introduce the top-spinner at will, and he also bowls the ball that goes with the arm into the batsman from the off. That brings many wickets, for there is no perceptible change of action and the victim plays for the non-existent turn the other way. He is also a master at varying flight and pace.

[breakout id=”1″][/breakout]

Added to his ability as a bowler is Lock’s magnificent short-leg fielding. In fact he can field anywhere. He is the longest and best thrower in the Surrey team. Lock never stood at short-leg until put there in his first match for Surrey in 1946 and then he held a hot catch off A.R. Gover’s bowling. An uncanny sense of anticipation enables Lock to effect some amazing catches with apparent ease.

A volatile person, he plays with tremendous enthusiasm. His voice in appeal is thunderous and, always on his toes, he leaps or tosses the ball into the air at the downfall of any batsmen. Some mistake his exuberance for showmanship, but surely Lock is the personification of that perpetual dynamic quality that keeps the game alive.