Tom Graveney, one of England’s greatest post-war batsmen, died on November 3, 2015. Here we remember his long and sometimes controversial career by revisiting his obituary from the 2016 Wisden Cricketers’ Almanack.

GRAVENEY, THOMAS WILLIAM, OBE, died on November 3, aged 88, nine days after his brother Ken. When it came to earning marks for artistic impression, or inspiring lines of poetic enchantment, few England batsmen have ranked higher than Tom Graveney. Not everyone was keen to rhapsodise: many of cricket’s more pragmatic minds – Len Hutton and Peter May among them – remained immune to his charms, and doubted his temperament for Test cricket. Like David Gower, Graveney became the subject of anguished national debate.

Perhaps only in England could a player of such natural talent have been treated with suspicion: Richie Benaud, Ian Johnson and Frank Worrell insisted he would have been an automatic selection in their sides. It was hard to argue with his weight of runs: in a career lasting more than 20 years, he scored nearly 48,000 at almost 45, including 122 centuries. Of English players since the war, only Geoff Boycott has been more prolific. And, in a fragmented Test career that began in 1951 and ended in 1969, he scored almost 5,000 at 44, with 11 hundreds. These were hardly the figures of a dilettante.

A youthful Tom Graveney with Len Hutton in 1951

A youthful Tom Graveney with Len Hutton in 1951

What was not up for debate was his easy grace. He had a long reach and a high backlift, and his off-side play was a study in elegance. Through leg he was less orthodox, hooking off the front foot, but he was never flustered. If cricket were destroyed and only Graveney survived, wrote Neville Cardus, it could be reconstructed “from his way of batting, from the man himself”. He relied on his top hand, allowing the bat to swing through the stroke like a pendulum. But, while he might have conveyed the impression that he was naturally gifted, he trained assiduously, always arriving first at the ground. “He would not miss his morning practice for anything,” said Ron Headley, a future team-mate at Worcestershire. “He liked to have a bat in his hand every day.” Graveney approached nets like an innings, batting defensively at first, then easing into a more attacking mode. His talent extended to his fielding, and he was a magnificent golfer.

His public persona was of an affable West Countryman who took top-flight sport in his stride. The reality was different. Born in Northumberland, he retained a propensity for plain speaking. “He was his own man and would tell you exactly what he thought,” said his Gloucestershire team-mate Frank McHugh. His single-mindedness shone through in two major controversies. In 1960, when he lost the Gloucestershire captaincy, he left immediately and spent a year playing Second XI and club cricket while qualifying for Worcestershire. And, nine years later, his international career was cut short when he appeared in a benefit match during a Test, and was suspended.

Graveney was only six when his father died, but a love of sport had already been instilled by visits to see Durham face touring teams at Ashbrooke in Sunderland. His mother remarried and in 1938 the family moved to Bristol, where his stepfather was employed as an accountant in the docks. At Bristol Grammar, Graveney showed promise at rugby, and at cricket shone more as a bowler. He left school at 17 and joined the Army early in 1945. The war was over before he could see active service, but he was posted to Egypt, where he found an agreeable role supervising sport for the troops, and his batting developed on the matting wickets used for service matches.

Graveney was much favoured for his grace through the off side

Graveney was much favoured for his grace through the off side

Graveney had every intention of remaining in uniform but, while on leave in the summer of 1947, he went to watch his brother Ken – now at Gloucestershire – in a benefit match for Charlie Barnett. They were short, and Tom ended up playing: although he made only 30-odd, his class and poise were obvious. As he unbuckled his pads, Barnett approached him with the offer of an alternative to life in khaki – a professional contract with Gloucestershire. It meant a pay cut, but Graveney accepted, and arrived for pre-season nets at Bristol in 1948. His potential was clear, but the runs did not immediately flow: he made nought on debut against Oxford University, and was dropped after a pair against Derbyshire. Salvation came when George Emmett was called up by England. Graveney got another chance and, while scoring 47 against Hampshire, something clicked. He finished the season with almost 1,000 runs, and his first century.

That winter he spent hours in Gloucestershire’s indoor nets learning to play more comfortably off the back foot. It did the trick: in 1949 he scored nearly 1,800 runs. “His elegant strokeplay stamped him as one of the best young batsmen in the country,” said Wisden. A first England call-up came against South Africa at Old Trafford in 1951. He was afflicted by nerves and his technique was tested on a damp pitch; but though he made only 15, he created a good impression. “Full of cultured promise,” said John Arlott on the radio. Graveney scored more than 2,000 runs at 48 that summer to earn a place in an understrength England team to tour the subcontinent. In the Second Test at Bombay he compiled 175 in eight hours, one of six centuries on a productive trip.

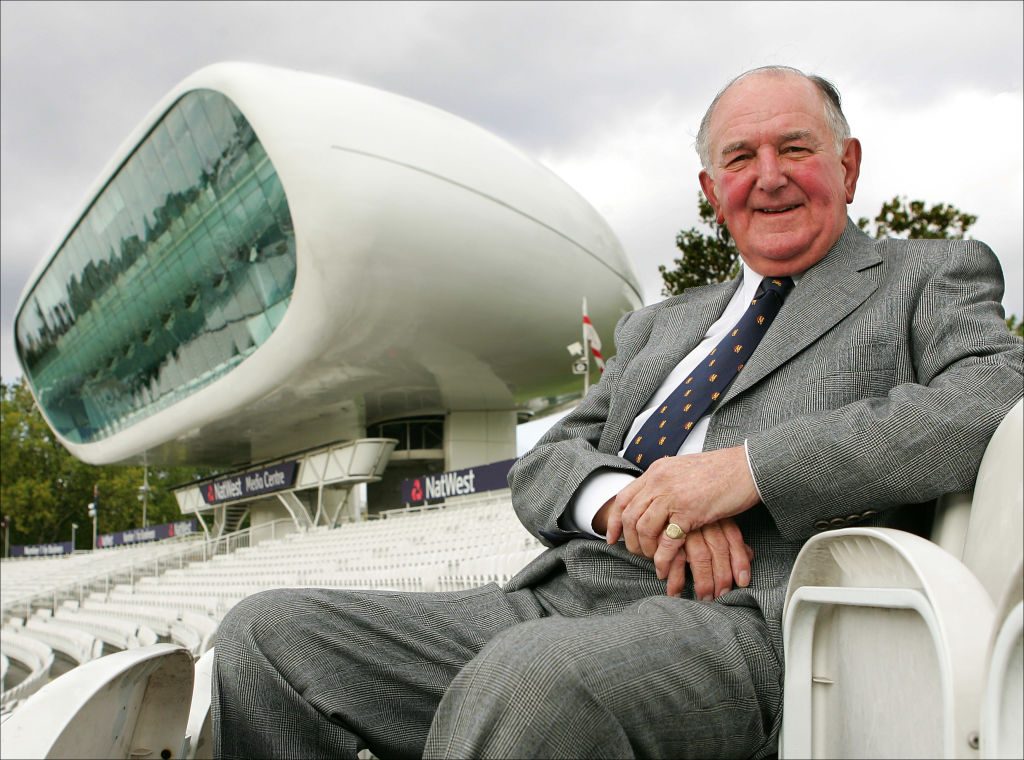

Graveney was MCC President for 2004-05

Graveney was MCC President for 2004-05

He played in all four Tests against India at home in 1952, but with a best of only 73. In county cricket, however, he was in imperious form. “Undoubtedly no brighter star has appeared in the Gloucestershire cricket firmament since the early days of Hammond himself,” said Wisden, who made him a Cricketer of the Year.

By his own admission, he was fortunate to keep his place throughout the 1953 Ashes, his one significant contribution a first-innings 78 at Lord’s. He and Hutton were in command against a tiring attack on the second evening when, an hour from the close, the captain ordered: “Right, that’s it for tonight.” Graveney retreated into his shell, and was bowled by Ray Lindwall next morning without addition. In the Caribbean that winter, Graveney hit two fours in an over on a day of funereal scoring. “We don’t want any of that,” said Hutton. “We’ve got to grind it out.” Graveney was convinced Hutton did not entirely trust any player with rosy cheeks.

His Test record gave his critics ammunition: too often he did not convert promising starts, and in Australia in 1954-55 he was dropped after the Second Test at Sydney. He was a spectator as Hutton’s team won the Ashes, and was unsure if he would play in the final match, again at Sydney, after being named in the 13. It rained for three days, and the batting order had still not been confirmed when Australia put England in: Hutton returned to the dressing-room and told Graveney he was opening. Don Bradman had remarked to Hutton that Graveney had the technique for the job, and he proved the shrewdness of that observation with his only century against Australia, passing three figures in scintillating style with four fours in an over off Keith Miller.

While he was in the field, the Old Trafford PA announced he had been summoned to a disciplinary hearing at Lord’s later that week

He bought his first car – a Ford Anglia – with his tour bonus, but endured a barren summer against the South Africans in 1955 (he kept wicket at Old Trafford when Godfrey Evans was injured) and was dropped after failing twice against Australia the following year. Recalled for the Fourth Test at Old Trafford, he withdrew with an injured hand, to the undisguised chagrin of chairman of selectors Gubby Allen, who thought Graveney was shying away from another failure before the squad was chosen for South Africa; according to one story, when May offered a sympathetic handshake, Graveney did not wince. In county cricket that summer he was unstoppable, leading the run-charts with 2,397 runs at nearly 50. But, when the tour party was named, he was not included. Graveney felt his mistake had been to beat Allen on the golf course.

Against that background the 1957 home series against West Indies might have represented his last chance. He made a duck at Lord’s, but in the Third Test at Trent Bridge he survived an early scare, glancing perilously close to Garry Sobers at leg slip, to make a glorious 258. He did not rate it his best Test innings, but it was probably the most important. He followed it with 164 at The Oval.

At Gloucestershire, he became captain in 1959, and led them to second place. They slipped back to eighth in 1960, and Graveney was asked to resign in favour of Tom Pugh, an Old Etonian who fulfilled the committee’s desire for an amateur captain. Graveney felt results had been reasonable, and that he was hardly responsible for the county’s worsening financial position. He stepped down just before Christmas, but matters turned ugly when Gloucestershire went back on a verbal agreement to allow him to join another county, and MCC rules prevented him from playing Championship cricket for a year.

There was much media interest when he arrived for pre-season nets at Worcestershire alongside fellow recruits Bob Carter, from Durham, and Yorkshire’s Duncan Fearnley. “We both had to qualify and it was good news for me because I played with him a lot,” said Fearnley. “He treated those Second XI and Birmingham League games as seriously as a Test match.” Graveney was allowed to play against the Australians and in the university matches, but it was not until 1962 that he would embark on a happy and fruitful second half of his career. His exile had also sharpened his appetite for Test cricket, and he averaged 100 against Pakistan.

But he struggled again on his third Ashes tour, in 1962-63, and there was a widespread assumption that, at 35, his Test career was over. Compensation came in the stately surroundings of New Road, where his game found fresh resolve; seamer Len Coldwell said Graveney had played for Gloucestershire but worked for Worcestershire. In 1964 and 1965 the club were county champions. When a supporter thanked Coldwell and new-ball partner Jack Flavell, Coldwell pointed at Graveney: “No, he won the Championship for us.” He was ever-helpful to fellow batsmen, and an inspirational figure to young bowlers. “Every ball I bowled, I would be looking to him for approval,” said Carter. He never departed from the rituals of the morning net, nor from putting his chewing-gum on his bat handle if he was not out overnight. “He did not watch the game until he was the next man in,” said Fearnley. “Then he would watch every ball intently.”

Despite his habitual modesty, Graveney felt he was the best batsman in the country during his years out of the Test arena. Eventually the clamour for a return could not be ignored. In 1966, surfing waves of goodwill, he made 96 on his comeback, against West Indies at Lord’s, followed by centuries at Trent Bridge and The Oval, where his brilliant counter-attacking partnership of 217 with John Murray turned the match. He scored heavily again the next summer, against India and Pakistan, and rated his 151 against Bedi, Prasanna and Chandrasekhar on a turning Lord’s pitch as his finest Test innings. In the 1968 Ashes, he stood in as emergency captain in Colin Cowdrey’s absence during the drawn Fourth Test at Headingley. His final Test century came against Pakistan in Karachi in 1968-69, more than 17 years after his first.

A guard of honour from both teams at the end of his last innings in the field at New Road

A guard of honour from both teams at the end of his last innings in the field at New Road

Graveney had been vindicated in his second coming as a Test batsman, but he knew it could not last. His benefit year was in 1969, and a businessman offered him £1,000 to play in a Sunday charity match at Luton – on the rest day of the First Test against West Indies at Old Trafford. What happened next was for ever disputed. Graveney insisted he called Alec Bedser, the chairman of selectors, explaining the situation; when he was refused permission to play in the benefit game, he asked to be left out of the Test squad. When his name was included, he assumed Bedser had agreed to his absence. It was only as he soaked in the bath on 56 not out at the end of the first day in Manchester that he was told the ban remained. Determined to collect his fee, Graveney took a desultory part in the match at Luton, but retribution was swift: next day, while he was in the field, the Old Trafford PA announced he had been summoned to a disciplinary hearing at Lord’s later that week. It was his 42nd birthday; he knew his international career was over. He was officially banned from the next three Tests, and never chosen again.

He stayed on at Worcester, where he had assumed the captaincy, until the end of the 1970 season, and was then briefly player-coach of Queensland. He was for many years the landlord of a pub near Cheltenham racecourse, and spent more than a decade as a BBC commentator, rekindling his love of the game. His job as an ICC match referee ended when he was appointed in 1992 to a West Indies-Pakistan series, and the Pakistan Cricket Board excavated some injudicious remarks he had made in the wake of the Shakoor Rana affair: “They’ve been cheating us for 37 years.” His greatest honour came in 2004, when he was the first former professional cricketer to be named president of MCC.

Perhaps the most famous of the many tributes to the fragile grace of Graveney’s batting, of which the cover-drive remained his signature shot, was by Alan Ross, who discerned “a player of yacht-like character, beautiful in calm seas, yet at the mercy of every change of weather”. Following the deaths of Bob Appleyard and Frank Tyson earlier in the year, he had been the last survivor of the stellar squad that brought home the Ashes in 1954-55. It was the end of a glorious era in English cricket.

The Wisden Cricketers’ Almanack 2018 is the 155th edition of ‘the bible of cricket’. Order your copy now.

Visit the Long Room for more long reads and features.