Gubby Allen played in the classic of 1930, and watched the fifty years later. In 1981, Wisden asked him for some reflections on the two.

The Test match against Australia at Lord’s in 1930 was my first. Now, 50 years later, presumably because I am, sadly, the only surviving member of that England team, I have been asked to record my impressions of, and draw some comparisons between, that match and the Centenary Test match against Australia at Lord’s last summer.

That the former was one of the great games in cricket history and the latter was not was due partly to chance. For one thing, the weather in 1930 was perfect. So, though on the slow side, was the pitch, which had been specially prepared, this being the first ever four-day Test match at Lord’s.

In 1980 it rained often enough and hard enough on the first three days to have confounded even the 1930 sides from providing as much entertainment and fine cricket as I believe they did half a century ago. To that extent, Chappell and Botham and their two sides were up against it from the start. On the other hand, I am sure that in 1930, in conditions similar to those on the Saturday of the Centenary Test match, play would have started much earlier than it did. In fact, looking back to the Thirties, when pitches were uncovered and there was much less covering generally, I think that play was often started too soon; but surely the pendulum has now swung too far in the opposite direction.

It must seem incredible to many who play and watch the game today that England could have made 425 in the first innings of a four-day match, as they did at Lord’s in 1930, and yet have lost. In reply, Australia scored 729 for six declared. In the last two hours 40 minutes on the second day, Australia went from 162 for one to 404 for two – 225 runs, that is, in 160 minutes, of which Bradman made 155.

At the start of the last day, England, in their second innings, were 98 for two, still 206 behind with Hobbs and Woolley out, and it needed a great innings of 121 in two and a half hours by Chapman to save the side from an innings defeat. In the end, Australia, losing three wickets (including that of Bradman) for 22 runs, had a minor crisis to surmount before winning with an hour to spare.

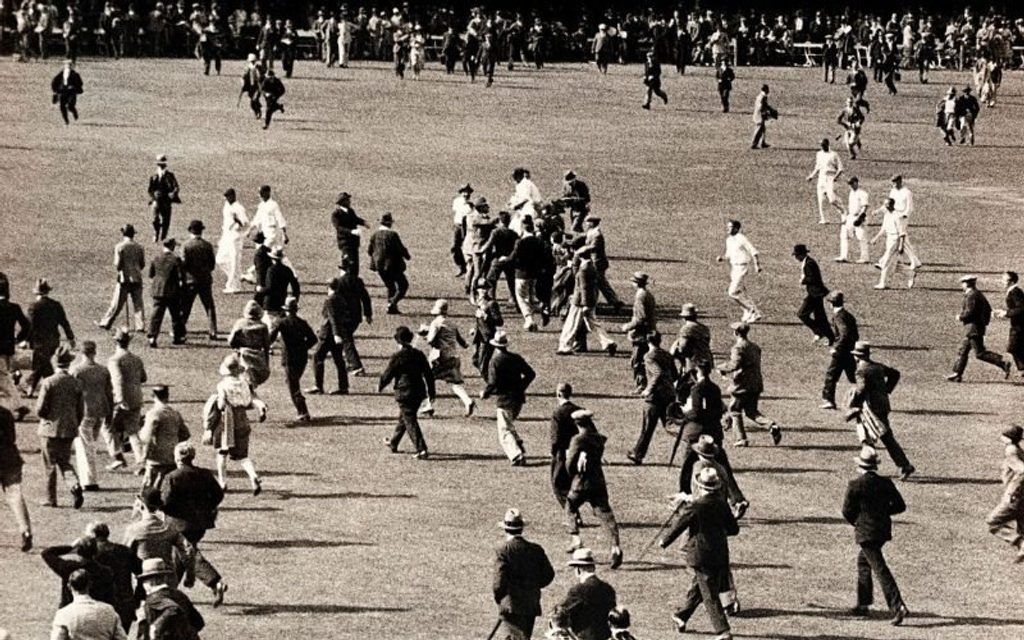

Spectators invade the pitch after Australia’s seven-wicket win

Spectators invade the pitch after Australia’s seven-wicket win

But this was the age of the batsman, the age before the lbw law was changed, and this was a batsman’s match throughout. The pitch, for the reason I have mentioned, was easy-paced, and the bowlers, the leg-spinners and White excepted, were perhaps slightly below standard, Tate by then being a little over the top.

For England the outstanding innings were those of Chapman and Duleepsinhji, though Woolley’s 41 in very quick time on the first morning was a gem. Duleepsinhji’s 173 in his first Test match against Australia was one of the most graceful exhibitions of batting I have ever seen: he was a superb player of spinners as he proved on this occasion. Chapman’s was a fine effort, particularly the second half of it, though he played and missed many times in his first fifty.

I can vouch for this as I was in with him, and he should have been out before scoring. I can see it now: he failed to spot Grimmett’s googly and hit a skier on the off side. Woodfull, Richardson and Ponsford all could have caught it easily, but at the last moment, no one having called, each left it to the other. Amidst much laughter and some apologies, all Grimmett said was, “Never mind, I’ll get him out next over.” When watching the Centenary match with Ponsford. I mentioned the incident to him. He remembered it well, but to our mutual enjoyment, he was disinclined to admit to more than a minor share of the guilt.

For Australia, the first four, Woodfull, Ponsford, Bradman and Kippax, all played fine innings, each in his own rather different style: Woodfull with his short backlift, very sure but always looking for runs; Ponsford mainly on the back foot or up the wicket to the spinners and a superb timer of the ball; Kippax a very elegant stroke-player on both sides of the wicket – and then, of course, Bradman.

The best comment on Bradman’s innings is probably his own. When asked which was the best innings he ever played he is on record as saying: “My 254 at Lord’s in 1930 because I never hit a ball anywhere than I intended and I never lifted one off the ground until the stroke from which I was out.” Some believe he was unorthodox. Well, perhaps he was when he was really on the rampage, but in defence and when necessary, none was more correct. It was his early judgment of length, his quickness of foot and his ruthless concentration, which made him the undoubted genius he was.

Bradman scored 974 runs at 139.14 from five Tests – a world-record aggregate for a single series

Bradman scored 974 runs at 139.14 from five Tests – a world-record aggregate for a single series

The Centenary Test match is a different story. As I have already said, conditions were unfavourable from the start. Even had MCC acquired an additional cover, and before the match the captains and umpires had been requested by the authorities to be rather less stern in their judgement as to fitness for play, I doubt if it would have helped greatly as it is always difficult to make a game flow once it has been subjected to frequent interruptions.

I hate saying it, but I do not think either looked a very good side. There were, of course, several high-class batsmen amongst them, and in Lillee certainly the best fast bowler in either match. Although perhaps not quite as fast as he was, his rhythm, his ability to move the ball and vary his pace, and his unbounded determination were a feature of the match.

For Australia, Wood played a sound first innings and Chappell two good– though for him rather subdued – innings. In form, with all his strokes going, Chappell must rank high amongst batsmen of our time. But in this match it was Hughes who caught the eye, at least mine. Of course he took some chances and had his moments of luck, particularly in the second innings, but he was reluctant to be dictated to, moved his feet well, and with a wholesome backlift was able and prepared to play all the strokes.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9edzxOff2uM

After 50 years one’s memory is hazy, but of one thing I am sure – his straight six off Old was unquestionably the best hit in either match, indeed possibly the most remarkable straight hit I have seen. To take two paces up the wicket to a fast-medium bowler of Old’s class and hit a flat skimmer on to the top of the Pavilion at Lord’s takes some beating. Goodness only knows where it might have gone had he, to use a golfing term, taken a slightly more lofted club.

For England, the batting, with two exceptions, was below Test match standard, even after making allowances for the excellent fast attack of Lillee and Pascoe and the fact that the match took place late in the season after a difficult series against some relentless West Indian fast bowling. Boycott showed his undoubted class in two typically determined innings. Technically he is head and shoulders ahead of any other batsman in England, indeed his technique is so good it is surprising he does not tear the attack apart more often.

Gower twice played some fine strokes and was beginning to look the batsman all Englishmen hope and believe he will be, only to get out to two bad shots. Unfortunately, Gooch, who is now an extremely good opener and a powerful striker of the ball, failed in both innings.

So much for my impressions of the two matches; now for some comparisons. My first and foremost must be regarding the pace at which they were played, and the Centenary match is a fair example of how the game has slowed down over the span of years. I may have some regrets about the present-day game, but this is my one real criticism of it. Statistics are often boring and can be unjust, but in this instance I think they are interesting and revealing in that they provide some indication as to how much and why this state of affairs has come about.

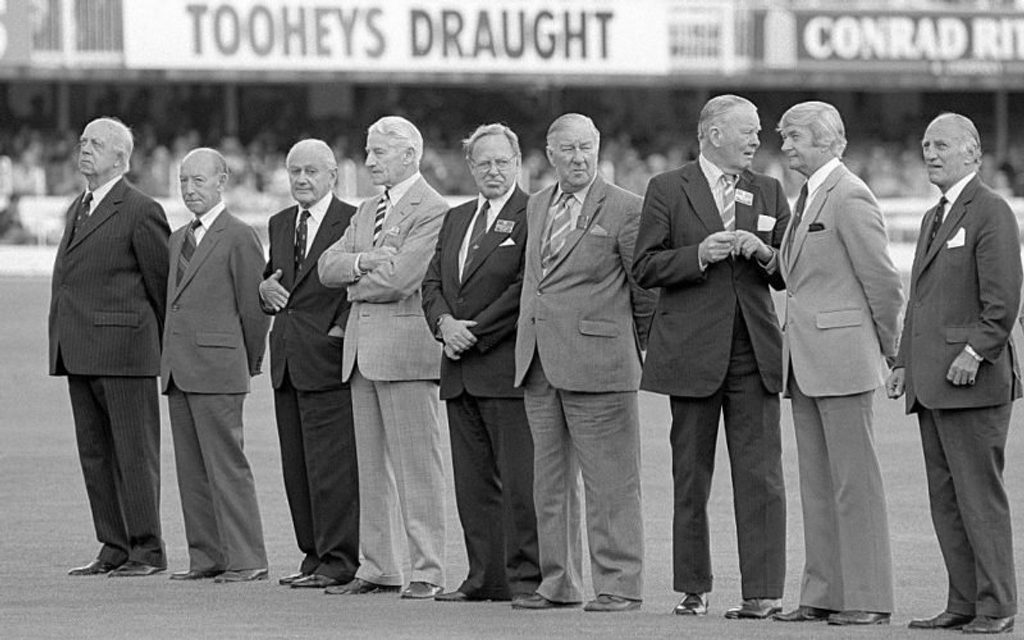

Former England and Australia Test captains (left to right): Bob Wyatt, Lindsay Hassett, Gubby Allen, Cyril Walters, Arthur Morris, Norman Yardley, Freddie Brown, Richie Benaud and Len Hutton assemble during the Centenary Test at Lord’s

Former England and Australia Test captains (left to right): Bob Wyatt, Lindsay Hassett, Gubby Allen, Cyril Walters, Arthur Morris, Norman Yardley, Freddie Brown, Richie Benaud and Len Hutton assemble during the Centenary Test at Lord’s

In the 1930 match, 1,601 runs were scored in 23 hours 10 minutes, that is at an average of 69 runs per hour, whereas in the Centenary match 1,023 were scored in 21 hours 7 minutes, an average of 48.4, per hour. A difference of 20 runs an hour is disturbing, to say the least; yet if one looks at the runs per 100 balls one finds very little between them, there being 53 runs in 1930 and 51.2 in 1980. If one then takes into account the importance nowadays attached by captains to containment and the present high standard of fielding, it is clear the batsmen must be exonerated.

And so, inevitably, to the over-rate. In 1930, 260 overs of pace and 245 of spin were bowled at an average of 21.50 an hour: in 1980, 210 overs of pace and 122 of spin were bowled at an average of 15.82 an hour. These figures for pace and spin suggest to me that it is not solely the predominance of fast bowling that is responsible for the loss of 5.68 overs an hour.

The endless discussions between bowlers and captains, the frequent changes in field-placing – and the waiting for new batsmen to reach the crease before making some of them – waste part of the time. But it is the absurdly long run-ups of many of the fast bowlers, and even of some of the medium-paced bowlers, often coupled with a funereal walk back to their marks, that are the real cause of the trouble.

For those who saw little or no cricket before World War Two, I can assure them one could count on the fingers of one hand the number of fast bowlers who ran more than 25 yards: nowadays one can count on the fingers of one hand those who do not – and some run 40 or 45 yards. Of course a few of these long-runners are a fine sight coming in, but please let us be spared their country strolls.