Jack Hobbs, the most prolific run-scorer in cricket history and perhaps England’s greatest batsman, died on December 21, 1963. At the time of his death, Wisden asked Neville Cardus, one of the game’s most famous writers, to provide their tribute.

Read more Almanack articles.

Previously from the almanack: John Arlott: Commentary legend & voice of post-war peace

Sir Jack Hobbs, the great batsman whose first-class cricket career spanned 30 years and brought him fame everywhere as a player second to none, was born in humble surroundings at No. 4 Rivar Place, Cambridge, quite close to Fenner’s, Parker’s Piece and Jesus College.

Christened John Berry Hobbs because his father’s name was John and his mother’s maiden name Berry, John – or Jack as he was always known – was the eldest of twelve children, six boys and six girls. His father was on the staff at Fenner’s and also acted as a professional umpire.

Sir Jack Hobbs – one of the greatest English batsmen of all time

Sir Jack Hobbs – one of the greatest English batsmen of all time

When Hobbs senior became groundsman and umpire to Jesus College, young Hobbs took immense delight in watching cricket there. During the school holidays, he used to field at the nets and play his own version of cricket with the College servants, using a tennis ball, a cricket stump for a bat and a tennis post for a wicket on a gravel pitch.

This primitive form of practice laid the foundations of his skill. Little more than ten years old at the time, young Jack tried to produce the strokes which he had seen players employ in college matches. The narrow straight stump helped him to appreciate the importance of a straight bat, and with the natural assets of a keen eye and flexible wrists he learned to hit the ball surely and with widely varied strokes.

Hobbs was self-taught and never coached, but he remembered all his life a piece of advice which his father gave him the only time the pair practised together, on Jesus College Close. Jack, facing spin bowling from his father, was inclined to stand clear of his stumps. “Don’t draw away,” his father told him. “Standing up to the wicket is all important. If you draw away, you cannot play with a straight bat and the movement may cause you to be bowled off your pads.”

When 12, Jack joined his first cricket team, the Church Choir Eleven at St. Matthew’s, Cambridge, where he was in the choir, and the first match in which he ever batted was for the choir of Jesus College who borrowed him, on their ground. He helped to form the Ivy Boys Club and they played both cricket and football on Parker’s Piece.

Ranjitsinhji practised there, and Hobbs watched his beautiful wrist-play wonderingly, but the hero of Jack’s boyhood was Tom Hayward, son of Dan Hayward who looked after the nets and marquees on Parker’s Piece.

Cricket became Jack’s passion and his supreme ambition was to be good enough to play for one of the leading counties, preferably Surrey, the county of his idol, Tom Hayward. Hobbs practised morning, noon and night, and when he knew that he would be busy during the day he rose at six and practised before he went to work.

Hobbs was the most accomplished batsman known to cricket since W.G. Grace

Hobbs was the most accomplished batsman known to cricket since W.G. Grace

Tom Hayward first saw him bat when the noted Surrey player took a team to Parker’s Piece for the last match of the summer in 1901, the season in which Jack played a few times for Cambridgeshire as an amateur.

In 1902, Hobbs obtained his first post as a professional – second coach and second umpire to Bedford Grammar School – and in the August of that year he helped Royston, receiving a fee of half a guinea for each appearance. He hit a fine century against Herts Club & Ground, so bringing immense joy to his father, but Mr Hobbs was not destined to see further progress by his son, for he died soon afterwards.

Tom Hayward was instrumental in Jack going to Surrey. A generous man, Hayward arranged a benefit for the widow Hobbs, and another friend of the family, a Mr. F.C. Hutt, asked Hayward to take a good look at Jack. Hobbs was set to bat for twenty minutes on Parker’s Piece against William Reeves, the Essex bowler, and Hayward was so impressed that he promised to get Jack a trial at the Oval the following spring.

Mr Hutt thought that Hobbs should also try his luck with Essex, but they declined to grant him a trial, and so, in April 1903, Hobbs went to Surrey. Immediately they recognised his budding talent and engaged him. A two years’ qualifying period had its ups-and-downs for Hobbs – he began with a duck when going in first for Surrey Colts at the Oval against Battersea – but soon his promise was clear for all to see.

In his first Surrey Club & Ground match he made 86 against Guy’s Hospital, and in his second qualifying year – 1904 – when he played several matches as a professional for Cambridgeshire, he scored 195 in brilliant style against Hertfordshire. His apprenticeship over, Hobbs commenced in 1905 the long and illustrious career with Surrey in first-class company which was to make his name known the world over and earn him a knighthood from the Queen – the first professional cricketer to receive the honour.

From the time he was awarded his county cap by Lord Dalmeny, afterwards Lord Rosebery, following a score of 155 in his first Championship match against Essex, Hobbs built up the reputation of the Master cricketer – a reputation perpetuated by the Hobbs Gates at the Oval and by his other permanent memorial, the Jack Hobbs Pavilion, at Parker’s Piece.

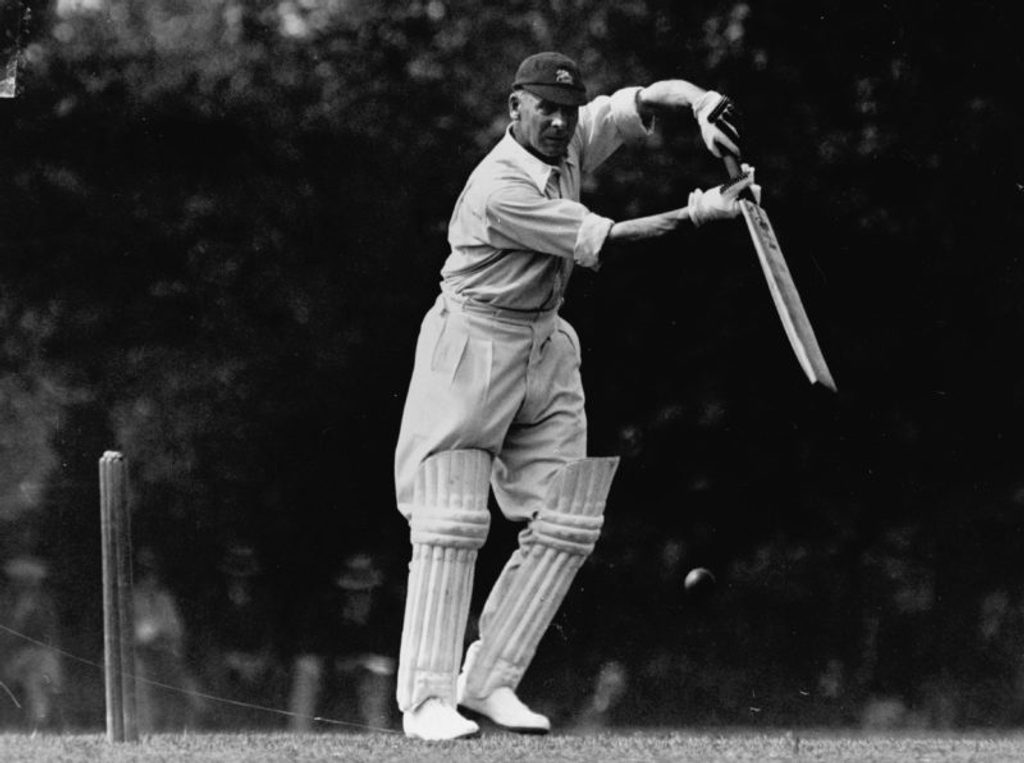

Hobbs plays a pull stroke

Hobbs plays a pull stroke

The tables of his achievements, given here, tell eloquently how thoroughly he deserves remembrance by cricket enthusiasts, but comparisons with W.G. will still be made.

From this point of view, Hobbs was, without argument, the most accomplished batsman known to cricket since W.G. Grace. In his career, Hobbs scored 61,237 runs with an average of 50.65 and scored 197 centuries. He played in 61 Test Matches. Other players have challenged the statistical values of Hobbs’s cricket. None has, since Grace, had his creative influence.

Like W.G., he gave a new twist or direction to the game. Grace was the first to cope with overarm fast bowling, the first to mingle forward and back play. Hobbs was brought up on principles more or less laid down by W.G. and his contemporaries left leg forward to the length ball. Right foot back to the ball a shade short, but the leg hadn’t to be moved over the wicket to the off.

Pad-play among the Victorians was not done. It was caddish – until a low fellow, a professional from Nottingham, named Arthur Shrewsbury, began to exploit the pad as a second line of defence – sometimes, in extremity, a first.

When Hobbs played his first first-class match for Surrey on a bitterly cold Easter Monday (April 24) in 1905, the other side, captained by W.G. was called The Gentlemen of England. Hobbs, then 22 years and four months old, scored 18 and 88 – taking only two hours making the 88. Grace contemplated the unshaven youth from his position of point. He stroked the beard and said: “He’s goin’ to be a good’ un.” He could not have dreamed that 20 years later Hobbs would beat his own record of 126 centuries in a lifetime – and go on to amass 197 before retiring, and receive a knighthood for services rendered.

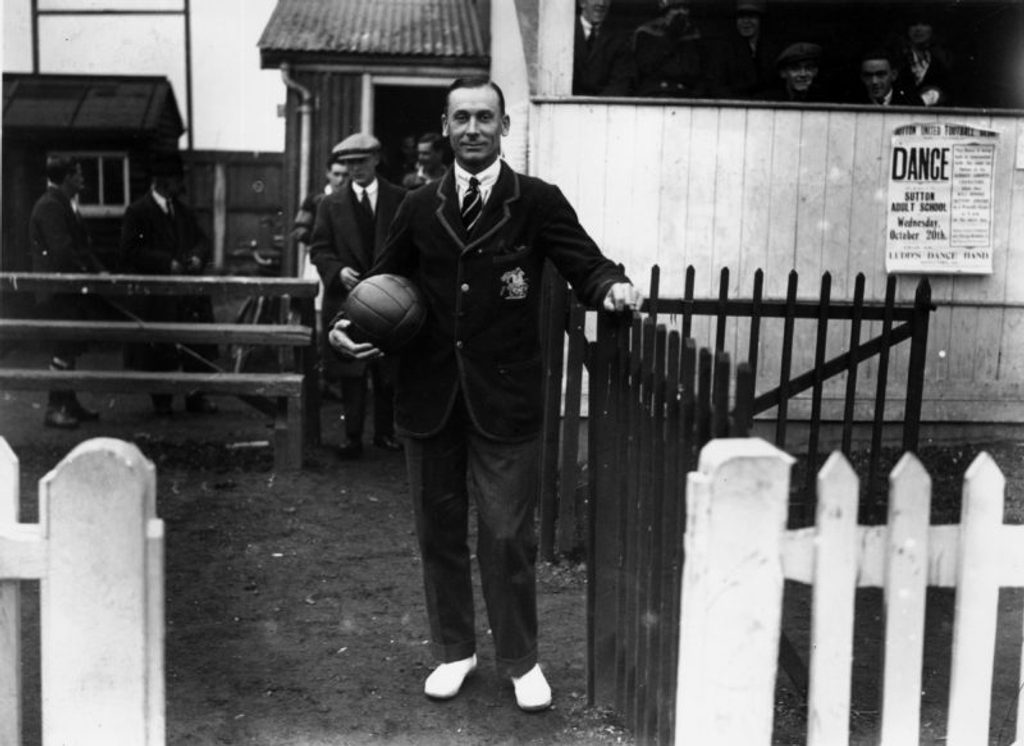

Guesting for a Dutch touring team against England in Ealing in 1937

Guesting for a Dutch touring team against England in Ealing in 1937

Hobbs learned to bat in circumstances of technique and environment much the same as those in which Grace came to his high noon. The attack of bowlers concentrated, by and large, on the off stump. Pace and length on good pitches, with varied flight. On sticky pitches the fast bowlers were often rested, the damage done by slow left-hand spin or right-hand off breaks.

Leg breaks were called on but rarely, then as a last resort, though already Braund, Vine and Bosanquet were developing back-of-the-hand trickery. Swerve was not unknown in 1905; there were Hirst, Arnold, Relf, Trott, and J.B. King swinging terrifically. But in those days only one and the same ball was used throughout the longest of a team’s innings. And the seam was not raised as prominently as on balls made at the present time.

In 1907, two summers after Hobbs’s baptism of first-class cricket, the South Africans came to this country, bringing a company of googly bowlers as clever as any seen since – Vogler (quick), Gordon White, Faulkner and Schwarz. Hobbs faced them only twice, scoring 18 and 41 for Surrey and 78 and 5 for C.I. Thornton’s XI at Scarborough.

J.T. Tyldesley, Braund, Jessop and Spooner also coped with the new witchcraft, so did George Gunn, who could cope with anything. Partly on the strength of his showing against the South Africans, Hobbs was chosen for his first overseas tour: 1907-1908 in Australia.

But it was two years later, when the M.C.C. visited South Africa, that Hobbs demonstrated quite positively that he had found the answer to the problems of the back-of-the-hand spinners. The amazing fact is that he made his demonstration on the matting wickets then used in South Africa. What is more, it was Hobbs’s first taste of the mat, on which the South African spinners were at their most viciously angular.

South Africa won this rubber of 1909-1910 by three wins to two. In the Tests Hobbs scored 539 runs, average 67.37; double the averages of England’s next best three run-makers: Thompson (33.77), Woolley (32.00), Denton (26.66) and Rhodes (25.11).

It was Hobbs who first assembled into his methods all the rational counters against the ball which turned the other way. Moreover, on all kinds of pitches, hard and dry, in this country or in Australia, on sticky pitches here and anywhere else, even on the gluepot of Melbourne, on the matting of South Africa, against pace, spin, swing, and every conceivable device of bowlers Hobbs reigned supreme.

His career was divided into two periods, each different from the other in style and tempo. Before the war of 1914-1918 he was Trumperesque, quick to the attack on springing feet, strokes all over the field, killing but never brutal, all executed at the wrists, after the preliminary getting together of the general muscular motive power.

The more his years increased the riper his harvests

The more his years increased the riper his harvests

When cricket was resumed in 1919, Hobbs, who served in the Royal Flying Corps as an Air Mechanic after a short spell in a munition factory, was heading towards his thirty-seventh birthday, and a man was regarded as a cricket veteran in 1919 if he was nearing the forties. Hobbs entering his second period, dispensed with some of the daring punitive strokes of his youthful raptures. He ripened into a classic. His style became as serenely poised as any ever witnessed on a cricket field, approached only by Hammond.

He scored centuries effortlessly now; we hardly noted the making of them. They came as the hours passed on a summer day, as natural as a summer growth. An astonishing statistical fact about The Master is that of the 130 centuries to his name in County cricket, 85 were scored after the war of 1914-1918; that is, after he had entered middle-age. The more his years increased the riper his harvests.

From the time of his forty-third to his forty-sixth birthday, Hobbs scored some 11,000 runs, averaging round about the sixties. Yet he once said that he would wish to be remembered for the way he batted before 1914. “But, Jack,” his friends protested, “you got bags of runs after 1919!” “Maybe,” replied Hobbs, “but they were nearly all made off the back foot.” Modest and true to a point. The Master knows how to perform within limitations. Hobbs burgeoned to an effortless control not seen on a cricket field since his departure. The old easy footwork remained to the end.

At Old Trafford, a Lancashire colt made his first appearance against Surrey. He fielded at mid-off as McDonald, with a new ball, opened the attack on Hobbs. After a few overs, the colt allowed a forward stroke from Hobbs to pass through his legs to the boundary. His colleagues, notably burly, red-faced Dick Tyldesley, expostulated to him “What’s the matter? Wer’t sleepin’?” – with stronger accessories. The colt explained or excused his lapse. He had been so much mesmerised watching Hobbs’s footwork as he played the ferocious speed of McDonald that he could not move.

It is sometimes said that Hobbs in his harvest years took advantage of the existing leg-before-wicket rule which permitted batsmen to cover their wickets with their pads against off-spin pitched outside the off-stump. True it is that Hobbs and Sutcliffe brought the second line of defence to a fine art. By means of it they achieved the two wonderful first-wicket stands at Kennington Oval in 1926 and at Melbourne two years later, versus Australia, each time on vicious turf. But, as I have pointed out, Hobbs’s technique was grounded in the classic age, when the bat was the main instrument in defence.

Always was the bat of Hobbs the sceptre by which he ruled his bowlers. In his last summers his rate of scoring inevitably had to slacken – from 40 runs an hour, the tempo of his youth, to approximately 30 or 25 an hour. In 1926, at Lord’s for Surrey versus Middlesex, he scored 316 not out in six hours 55 minutes with 41 boundaries – a rate of more than forty an hour, not exceeded greatly these days by two batsmen together. And he was in his forty-fourth year in 1926, remember.

It was in his wonderful year of 1925 that he beat W.G.’s record of 126 centuries, and before the summer’s end gathered at his sweet will 3,024 runs, with 16 hundreds, average 70.32. He was now fulfilled. He often got himself out after reaching his century. He abdicated.

He extended the scope of batsmanship, added to the store of cricket that will be cherished

He extended the scope of batsmanship, added to the store of cricket that will be cherished

Those of us who saw him at the beginning and end of his career will cherish memories of the leaping young gallant, bat on high, pouncing at the sight of a ball a shade loose, driving and hooking; then, as the bowler desperately shortened his length, cutting square, the blow of the axe – a Tower Hill stroke.

Then we will remember the coming of the regal control, the ripeness and readiness, the twiddle of the bat before he bent slightly to face the attack, the beautifully timed push to the off to open his score – the push was not hurried, did not send the ball too quickly to the fieldsman, so that Hobbs could walk his first run.

I never saw him make a bad or a hasty stroke. Sometimes, of course, he made the wrong good stroke, technically right but applied to the wrong ball. An error of judgement, not of technique. He extended the scope of batsmanship, added to the store of cricket that will be cherished, played the game with modesty, for all his mastery and produce, and so won fame and affection, here and at the other side of the world. A famous fast bowler once paid the best of all compliments to him – “It wer ‘ard work bowlin’ at ‘im, but it wer’ something you wouldn’t ‘ave missed for nothing.” Let Sir Jack go at that.

The Jack Hobbs Gate at The London Oval

The Jack Hobbs Gate at The London Oval

Other tributes:

Andrew Sandham: Jack was the finest batsman in my experience on all sorts of wickets, especially the bad ones, for in our day there were more bad wickets and more spin bowlers than there are today. He soon knocked the shine off the ball and he was so great that he really collared the bowling. He could knock up fifty in no time at all and the bowlers would often turn to me as if to say Did you see that? He was brilliant. Despite all the fuss and adulation made of him he was surprisingly modest and had a great sense of humour.

Herbert Strudwick: On any type of wicket, he was the best batsman in my experience, a first-class bowler if given the chance, and the finest cover point I ever saw. He never looked like getting out and he was just the same whether he made 100 or 0. I remember G.A. Faulkner after an England tour in South Africa, saying to Jack: “I only bowled you one googly.” “Why,” said Jack, “I did not know you bowled one.” Faulkner said, “You hit the first one I bowled for 4. If you did not know it how did you know it would turn from the off?” “I didn’t,” answered Jack. “I watched it off the pitch.”

Herbert Sutcliffe: I was his partner on many occasions on extremely bad wickets, and I can say this without any doubt whatever that he was the most brilliant exponent of all time, and quite the best batsman of my generation on all types of wickets. On good wickets, I do believe that pride of place should be given to Sir Don Bradman. I had a long and happy association with Sir Jack and can testify to his fine character. A regular church-goer, he seldom missed the opportunity to attend church service on Sunday mornings both in England and abroad. He was a man of the highest integrity who believed in sportmanship in the highest sense, teamwork, fair-play and clean-living. His life was full of everything noble and true.

Percy Fender: Jack was the greatest batsman the world has ever known, not merely in his generation but any generation and he was the most charming and modest man that anyone could meet. No-one who saw him or met him will ever forget him and his legend will last as long as the game is played–perhaps longer.

George Duckworth: My first trip to Australia in 1928 was Jack’s last and I remember with gratitude how he acted as a sort of father and mother to the young players like myself. Always a boyish chap at heart, he remained a great leg-puller. When 51 he promised to come up and play in my benefit match in 1934 and despite bitterly cold weather he hit the last first-class century of his career. He told me he got it to keep warm!

A legendary cricketer and an unforgettable man

A legendary cricketer and an unforgettable man

Frank Woolley: Jack was one of the greatest sportsmen England ever had, a perfect gentleman and a good living fellow respected by everyone he met. I travelled abroad with him many times to Australia and South Africa, and I always looked upon him as the finest right-handed batsman I saw in the 30 years I played with and against him.

Wilfred Rhodes: He was the greatest batsman of my time. I learned a lot from him when we went in first together for England. He had a cricket brain and the position of his feet as he met the ball was always perfect. He could have scored thousands more runs, but often he was content to throw his wicket away when he had reached his hundred and give someone else a chance. He knew the Oval inside out and I know that A.P.F. Chapman was thankful for his advice when we regained the Ashes from Australia in 1926.