Written shortly after Sir Donald Bradman’s death in 2001, Gideon Haigh looked at the legacy of the greatest batsman ever to grace the game.

Gideon Haigh is a cricket writer and historian. His most recent book is Crossing the Line: how Australian cricket lost its way

This article was first published in the 2002 edition of the Wisden Cricketers’ Almanack

The story of Sir Donald Bradman always involved more than cricket – more even than sport. One can only marvel at the statistics, and the one batting average that nobody need ever look up. Yet, in its degree and duration, especially in Australia, Bradman’s renown is as much a source of wonder: he was, as Pope wrote of Cromwell, “damned to everlasting fame”.

Few figures, sporting or otherwise, have remained an object of reverence for more than half a century after the deeds that formed the basis of their reputation. Fewer still can have justified an autobiography at the age of 21, and the last of many biographies at the age of 87, without surfeiting or even satisfying public curiosity. But with Bradman’s death on February 25, 2001 comes a question: what difference will it make to his legend now that, for the first time, it has obtained a life independent of his corporeal existence?

On the face of it, the answer appears to be: not much. In Australia, the Bradman story detached from the Bradman reality some time ago, taking on the qualities of myth: as defined by Georges Sorel, a faith independent of fact or fiction, where the normal processes of attestation and falsification are suspended by unconscious agreement. In the 1990s, in particular, a sort of cultural elision turned Bradman from great batsman to great man: by prime minister John Howard’s lights, “the greatest living Australian”, elevated not merely by his feats but by “the quality of the man himself “. Inspired by Bradman, Howard claimed, Australians could make “any dream come true”, and “not just in cricket but in life”.

This was a new experience for Australians. Poet and critic Max Harris once declared that “the Australian world is peopled by good blokes and bastards, but not heroes”. Yet, by the end of his life, Bradman was not merely a “hero”; he had also been, in effect, retrofitted as a “good bloke” – that peculiarly Australian formulation implying, essentially, someone like everybody else.

Bradman walks out to bat at New Road, Worcester on his final tour of England in 1948

Bradman walks out to bat at New Road, Worcester on his final tour of England in 1948

The actuality is, of course, that Bradman was an individual to whom few beyond his immediate family circle were close, whose private life was sedulously guarded, and whose innermost convictions went mostly unaired; his “good blokeness” is, accordingly, more or less unascertainable. But, as Sorel observed: “People who are living in this world of myths are secure from all refutation.”

Why this happened can only be conjectured. Perhaps it was the self-image as a sports-loving nation to which Australians cling with such tenacity. Perhaps it was part of the recrudescence of Australian conservatism (it’s hard to imagine Howard’s republican predecessor, Paul Keating, singling Bradman out as the “greatest living Australian”; indeed, perhaps that partly accounts for his electoral failure).

It may be as simple as Bradman keeping his head while all about him were losing theirs. He avoided the public eye, courted no controversies and scorned fame’s usual accoutrements. It would be an exaggeration to describe him as an outstanding citizen, at least as this is commonly understood: he was not a conspicuous philanthropist or supporter of causes, and the duty to which he devoted himself most diligently was simply being Donald Bradman, tirelessly tending his mountainous correspondence and signing perhaps more autographs than anyone in history. But there is no doubt that, standing aloof from modern celebrity culture, he retained a dignity and stature that most public figures sacrifice.

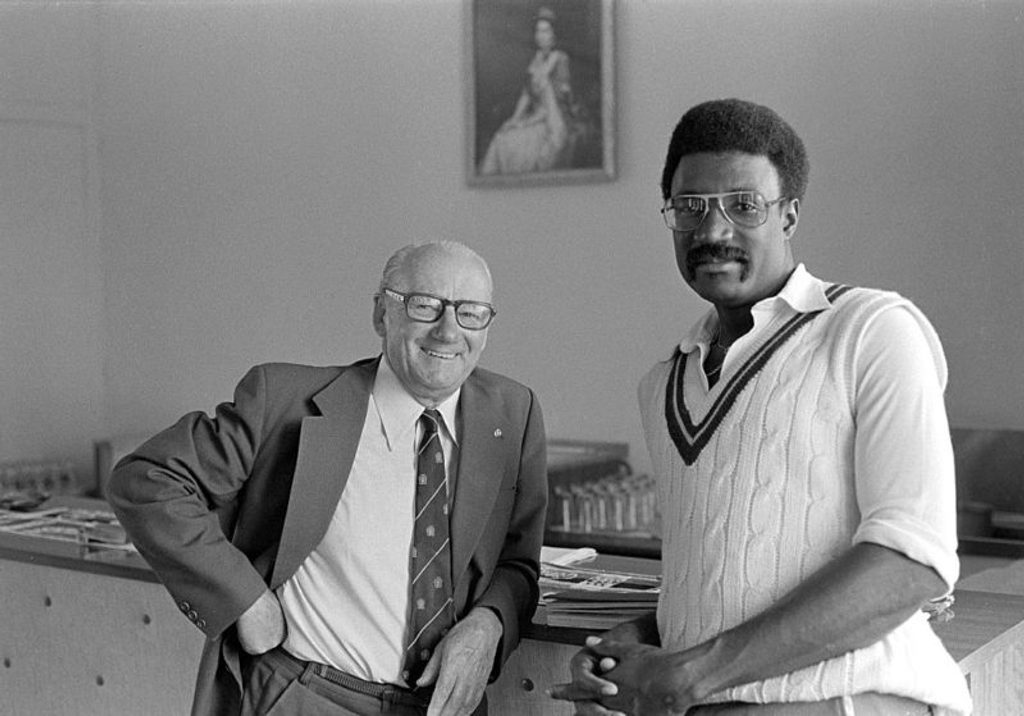

Bradman with Clive Lloyd in 1980

Bradman with Clive Lloyd in 1980

This being the case, it may be that the “greatest living Australian” segues smoothly into becoming the greatest dead one: Bradman certainly won’t be doing anything controversial now. But there are reasons against this progression: countries move on, palates jade, reputations are reassessed. There is already something anomalous about Bradman’s standing in Australia. National heredity and heritage during his playing career were almost exclusively British; as Dr Greg Manning has noted, Australia’s cultural homogeneity in the 1930s and 1940s was a precondition of the Bradman phenomenon. But since the late 1980s, British and old Australian components have accounted for less than half Australia’s population.

Even the idea of a monolithic Australian mourning of Bradman’s death was mostly a media assumption. The Chaser, a satirical newspaper, expressed this drolly with a story headlined: “Woman unmoved by Bradman’s death”. This fantasised about a 42-year-old woman who “surprised reporters when she was unable to recite Bradman’s famous batting average or other miscellaneous statistics”, who “denied suggestions the cricketer had been an inspiring influence on her life, and said she had no regrets whatsoever that she never saw him play”.

A significant role in the ongoing Bradman story will be played by the Bradman Museum at the cricketer’s boyhood home of Bowral in the New South Wales southern highlands. So far, the museum is a success story, as unique as its eponymous inspiration: a collecting institution for cricket that is largely self-funding, thanks partly to royalties from the Bradman name, worth between a quarter and half a million Australian dollars annually. And for this, Bradman himself can take a deal of credit. It was he, says the museum’s thoughtful curator, Richard Mulvaney, who “recognised that the museum would always have problems getting enough money to do the things it wanted to do”, and 10 years ago vouchsafed the commercial rights to his name and image. “We wouldn’t have dared ask,” says Mulvaney.

The Bradman Museum in Bowral

The Bradman Museum in Bowral

The museum’s future financial security was consolidated in August 2000 by an unforeseen consequence of the South Australian government’s decision to rename an Adelaide thoroughfare in honour of its favourite adopted son. When several businesses in the new Sir Donald Bradman Drive proposed exploiting their location in advertising, the Bradman family sought government intervention.

A sex shop provided, as it were, the most convincing argument for prophylaxis. “When the sex shop registered as Erotica on Bradman,” Mulvaney recalls, “we couldn’t have had a better example of the ways the name could be misused.” The subsequent amendment to Australia’s Corporations Law – preventing businesses from registering names that suggested a connection with Bradman where it did not exist – invested the Don with a commercial status previously the preserve of members of the royal family. But there was some sense to it, and the amendment has already proved its worth in the relative scarcity of necrodreck in Australia after Bradman’s death. In the longer term, too, it should secure for cricket the financial fruits of the Don’s legacy, for which the game can be grateful.

Batting with Colin Cowdrey in 1974

Batting with Colin Cowdrey in 1974

Enhanced power over the Bradman franchise sets the museum challenges. Its charter is to be “a museum of Australian cricket commemorating Sir Donald Bradman”. The legislation, explicit acknowledgment that Bradman’s name is a commodity with commercial value, subtly firms the emphasis on the latter role – something the museum recently recognised by signing an agency agreement for the exploitation of the name with Elite Sports Properties, a six-year-old sports management group now owned by London-based Sportsworld Media plc.

To be fair, Mulvaney perceives the dilemma. He is adamant that the museum will not, in his watch, become a one-man hall of fame: “While it’s in my interest to continue putting Bradman’s name forward, we shouldn’t take his name out of context. We have to be careful that we don’t allow excesses where the name takes on a completely different meaning.” The responsibilities inherent in ESP’s role also weigh heavily on their Andrew Stevens. “We feel very honoured to be representing the greatest Australian icon who ever lived,” he says. “And protecting it, which is quite daunting. It’s very precious. In fact, if someone strikes out at it, or is reckless with it, you tend to feel quite aggrieved.”

Inspecting one of The Don’s bats at the Bradman Museum

Inspecting one of The Don’s bats at the Bradman Museum

To how much protection, though, is Bradman entitled? And what constitutes “recklessness” where the name is concerned? These questions were raised in 2001 in an episode involving two letters, from Bradman to Greg Chappell, dating from the World Series Cricket schism in 1977. After defecting to Kerry Packer’s enterprise, Chappell found himself persona non grata in his adopted state of Queensland, and confided to a Brisbane Telegraph journalist some disparagements of the quality of local cricket administrators that Bradman had made to him some years earlier. When these were published, however, Chappell received a letter of rebuke for what Bradman viewed as a breach of trust. An exchange of correspondence followed in which Bradman enlarged on certain personal philosophies, as well as lamenting the frequent press misrepresentation to which he had been subject.

These were important artefacts. They evoked both the passion of the moment – for this was a time when tempers in cricket were frayed on all sides – and the personality of the writer. In some respects, it is from such flashes of candour that biographies are built; thus Plutarch’s famous remark in his life of Alexander the Great that “very often an action of small note, a short saying, or jest, will distinguish a person’s real character more than the greatest sieges or the most important battles”.

But when the letters were auctioned by Christie’s in July 2001, Chappell was roundly censured for another breach of trust, that of Bradman’s privacy. An anonymous consortium of businessmen styling themselves SAVE – Some Australians Value Ethics – intervened to purchase the letters, plus three others, for $A25, 870. They were presented to Mulvaney at the MCG on what would have been the Don’s 93rd birthday.

Even ignoring the question of whether it is possible to breach the privacy of the dead, it was a curious interlude. It went unremarked, for example, that the letters had previously been quoted from, without protest, in Adrian McGregor’s excellent 1985 Chappell biography. At best, SAVE’s intercession was a well-meaning attempt to avoid media sensationalising, which perversely made the letters’ contents seem more sensational than they were; at worst, it evinced a disconcerting cultural timidity in Australia, a squeamishness about anything other than the “approved” version of the Bradman story. In an interview with Sporting Collector, Mulvaney was quoted as saying that the Museum “considered the contents not necessarily to be in the public interest” and that it had “no option but to keep them private” – which made it sound like an issue of national security.

In an interview for this article, Mulvaney said that the magazine had misrepresented his views: his concern was purely with copyright, which he felt Christie’s had breached by reproducing the letters in its catalogue, and he insisted that the museum had no wish to inhibit study of Bradman material. However, when permission was sought to quote from the letters here, Sir Donald’s son, John, withheld it; he stated, albeit politely, that this was his present policy on all such enquiries.

One can sympathise with John Bradman’s position. No policy will satisfy everyone. Permission for all will invite excess and exploitation; permission for some will smack of favouritism; permission for none will be construed as censorship. Yet attempting to control what is published about Bradman in such a way will carry risks. Revisionists will move in regardless; indeed, they already are.

In November 2001, The Australian published two articles concerning “The Don We Never Knew”, the work of a foot-slogging journalist, David Nason. One revealed what appeared as vestiges of a family rift between the Don and his Bowral kin, disclosing the view of Bradman’s nephew that “Don Bradman only ever cared about Don Bradman”; the second examined how the alacrity with which Bradman took over the defunct stockbroking firm of the disgraced Harry Hodgetts antagonised Adelaide’s establishment.

Much the same criticisms of invasiveness were advanced as in the Chappell case. Mike Gibson, a columnist for Sydney’s Sunday Telegraph, thought the first article “pathetic”, “despicable”, “bitter and twisted”; the second he dismissed as lese-majesty: “You know, I couldn’t be bothered reading it. First, his family. Then, his finances. I couldn’t stomach any more smears against someone who cannot answer back because he’s dead.”

Yet what was truly noteworthy about the articles was not that they appeared, but that nothing resembling them had appeared before, that none of Bradman’s soi-disant “biographers” had treated his family and financial lives other than perfunctorily. Indeed, it may be that Bradman’s most ardent apologists end up doing him the gravest disservice. Identifying a great sportsman isn’t difficult: the criteria are relatively simple. Designating a great man entails rather more than a decree, even prime ministerial; some intellectual and historical contestation must be involved. Credulity invites scepticism – and, unlike trade names, reputations cannot be declared off limits by the wave of a legislative wand.