Learie Constantine was the most electrifying talent in world cricket in the 1930s. His efforts on West Indies 1939 tour of England earned him a Wisden Cricketer of the Year award.

The 1939 series marked Learie Constantine’s farewell to Test cricket, but he went on to achieve much more outside the game, including becoming the first black peer to sit in the House of Lords.

Cricket has known few more compelling figures than Learie Nicholas Constantine of the West Indies. To the passionate love for the game which inspires so many of his countrymen, and to the lissomness of limb, the rapidity of vision and the elasticity of muscle which the climate of those islands engenders, he adds qualities peculiarly his own, so that whether batting, bowling or fielding he becomes the centre of all interest.

So great has been his genius that his non-success with the bat in Test matches gives cause for wonderment till we read, as was once written of him, “the spirit of adventure, the sheer pleasure of enjoying the game, the desire to exploit rather than to employ his marvellous powers, always lure him into attempting the most impossible strokes.” And who will deny that he has been all the more intriguing because of his emphatic rejection of the ordinary?

Born near Port of Spain, Trinidad, on September 21, 1902, he had a cricket enthusiast in his father, LS, who was a member of the first West Indies team to visit England in 1900. All the family would practise together, with Constantine’s mother often keeping wicket and his uncle Victor Pascall joining in the bowling.

The father was insistent on the virtues of fielding, and innumerable miraculous catches show how well his son learned his lesson. In those scattered islands, opportunities for first-class matches are infrequent, and Constantine, too, had early set himself to study for the law, but so obvious were his talents that, after playing in only three big games he was told to hold himself in readiness to sail for England in 1923. That team, captained by HBG Austin and with G Challenor as its brightest star, did much to win Englishmen’s admiration, and Constantine earned widespread praise for his fielding at cover-point.

In the winter of 1925/26 he played four times, with moderate results, against the MCC team captained by the Hon. FSG Calthorpe, but by constant application – he was teaching himself to be a really fast bowler and a superb slip fielder – his full powers became developed, and when he came to England in 1928 he jumped right into fame. True that in the three Tests to which the West Indies were then first admitted, he made only 89 runs and took no more than five wickets, but in all first-class games he was second in the batting and first in the bowling with 1,381 runs and 107 wickets. He also made 29 catches, many of them brilliant in the extreme.

Some of his all-round performances were astonishing, especially that against Middlesex in June. After the county had declared at 352-6, the West Indies lost five wickets for 79, but Constantine then made 86 in less than an hour. In Middlesex’s second innings, he took 7-57, with 6-11 in his second spell, and then won the match for his side by three wickets with 103 in an hour.

During the tour he had an enormous amount of work to do, but his stamina and enthusiasm overcame everything, and a finer season’s hitting, fast bowling and slip-fielding it is not easy to remember. At the end of it Constantine signed forms for the Nelson club in the Lancashire League, a step which, if criticised, was eminently sensible, for that form of game suited him admirably, and he was also enabled to continue his law studies in England. With him cricket has not overruled every other interest in life. In between his first two seasons with Nelson he played for the West Indies against the MCC team of 1929/30.

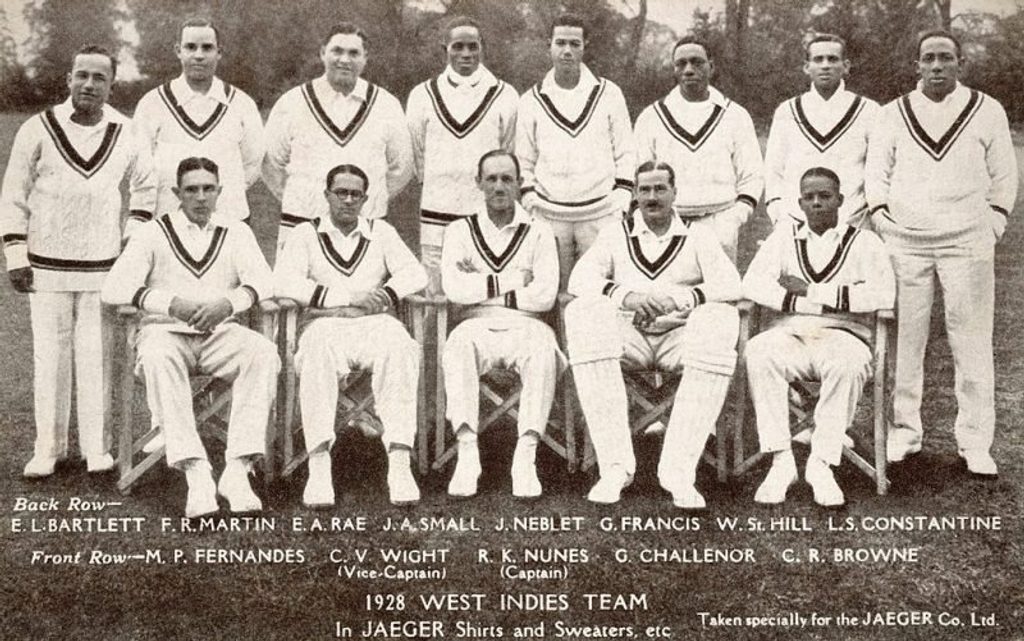

The West Indies side that toured England in 1928

The West Indies side that toured England in 1928

The following winter he was in Australia with GC Grant’s team. Like the other fast bowlers, Griffith and Francis, he found the pitches less quick than he had been led to expect, but he was again the all-rounder of the side with 708 runs and 47 wickets. His slip catching was the talk of the Commonwealth. When the West Indies, still under Grant, came to England in 1933, Nelson could release Constantine for only five matches, one of which was the second Test at Manchester. In this he came off with the bat, making a smashing 64 in the second innings. The controversy about “body line” which rendered this match somewhat notorious is most illuminatingly discussed in his book Cricket and I.

It was only fitting that he who had done so much for the cricket of the West Indies should share in their triumph when, defeating RES Wyatt’s team in two of the three finished Tests of 1934/35, they won the rubber for the first time in history. His fast bowling, with that of Martindale and Hylton, was described as the best in the world, and he had a great time in the second match, which he won by dismissing Leyland when only one more ball was possible. He made 90 in the first innings, 31 in the second and took five wickets for 52 (2-41 and 3-11). All-round achievement in such matches had long eluded him. It could hardly have come at a better time.

To his doings last season and to the manner of his play at the age of 36 reference is made in other parts of the Almanack. A cricketer who will never be forgotten, who took great heed that all nature’s gifts should be, as it were, expanded by usage, a deep thinker and an athlete whose every movement was a joy to behold.